By Rajiv Bhatia, MD, MPH and Jeffrey Klausner MD, MPH

On March 19, facing uncertainty as to whether the state’s hospital capacity would meet the needs of the Covid-19 epidemic, the California Department of Public Health ordered everyone in the state to stay home, effectively ending normal economic and social routines. Weeks after that indefinite order, the pace of the epidemic has thankfully slowed, and many hospitals — now retooled to manage increased Covid-19 demand — are well under capacity.

Without either proven pharmacological treatments or an effective vaccine, we’ll be living with Covid-19 for the foreseeable future. California needs to quickly establish a consensus for the next steps to manage the epidemic in ways that are least restrictive to individual liberties.

Sign-up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best content about life in the Bay Area in your inbox every week. What could go wrong?

California, and other states for that matter, should not wait for nor rely on a national strategy. The epidemic will have different dynamics in different regions at different times. By more effectively using monitoring data, the intensity of the response can be determined based on the needs of each geographical region.

Shelter-at-home orders were a decisive and precautionary maneuver in the face of uncertainty about our capacity for a medical response. Yet the current order to stay at home is blunt, is no longer required everywhere, and will be harmful in myriad ways if continued. Epidemics are always local and regional phenomena; in parts of the state where case rates are low, where new hospital admissions have been low or are now declining, and where adequate hospital reserve capacity exists, people should be able to safely exit home quarantine.

We believe it’s now imperative to advance a public discussion on how we proceed from here, not only to improve and refine our strategies but also to mobilize the necessary talent and collective action to realize them.

Our goal in the near term should be to monitor and moderate the pace of the Covid-19 epidemic so that we can ensure both maintaining adequate hospital capacity and preserving basic human needs and constitutional freedoms. This will be a balancing act. We can aim for a state in which some will continue to acquire Covid-19 and where our health care system can manage this demand.

We take these positions as physicians deeply committed to protecting health, as health scientists viewing events critically, and as former deputy health officers of San Francisco who are well aware of the responsibilities and challenges of public servants.

Executing this strategy will require closely monitoring the pace of the epidemic, expanding our capacity to promptly test, supporting those required to isolate, and stepping up and down from different intensities of public interventions when needed.

The primary strategies to moderate the effects of Covid-19 should include promptly testing those with suggestive symptoms, isolating those both symptomatic and diagnosed, notifying close contacts of the diagnosed, and protecting populations most vulnerable to morbidity and mortality. Early recognition of symptoms, confirmatory testing, and subsequent isolation reduces the time infected individuals spread infection. Contact notification may prompt early personal behavior change, more timely recognition of symptoms, self-quarantine, and earlier testing. Those at higher risk for severe illness, including the elderly and those with chronic diseases, should limit their contacts. Regular screening of all people in places where vulnerable populations live and prompt investigations of any infections in these places can reduce the infections most likely to lead to poor outcomes and death.

Currently, California has significant gaps in the infrastructure needed to implement those basic public health strategies. We need to grow our testing capacity much further, ensure material and emotional support for those requiring isolation, and develop and evaluate interventions on how best to notify close contacts. We are encouraged that, on April 13, California Gov. Gavin Newsom articulated those priorities for the next phase of the state response.

Moving forward though, restricting residents’ personal movement must no longer be considered an all-or-nothing strategy. In March, California instituted a number of strong interventions in quick succession. Simultaneously, many people changed their behaviors based on the growing awareness about the virus, its spread, and its impacts — schools and daycare facilities closed, businesses and other institutions required people to work from home, and so on. Evidence from areas that experienced the epidemic before us shows that selective and targeted interventions short of wholesale home quarantine were effective in lowering disease transmission. As alternatives to universal shelter-at-home orders, officials can implement various interventions to restrict personal movement and limit person-to-person contact — such as prohibiting large indoor social gatherings and work- or school-at-home policies for those who are ill or vulnerable — in a more selective and progressive way in order to achieve our primary objective of keeping hospitals from being overwhelmed.

Priority actions

Immediately, we need to establish clarity and consensus on our societal goals for going forward and establish the right measures and targets to evaluate our progress. “Flattening the curve” does not mean eliminating infections; it means controlling the pace of infections at a level where our health systems can cope.

We should also establish the appropriate geographical regions, not confined by political boundaries, for measuring and calibrating our actions. This will require augmenting our surveillance and testing capacities for Covid-19 along with new mandates for reporting by laboratories and hospitals. We will need transparent mechanisms to share data, review progress, and adapt to new knowledge and circumstances. Both the press as well as people will need to be engaged critically to demand this transparency.

We should begin to test a random sample of the population every day to get a better handle on the actual prevalence of Covid-19 infection and how this prevalence is changing with time.

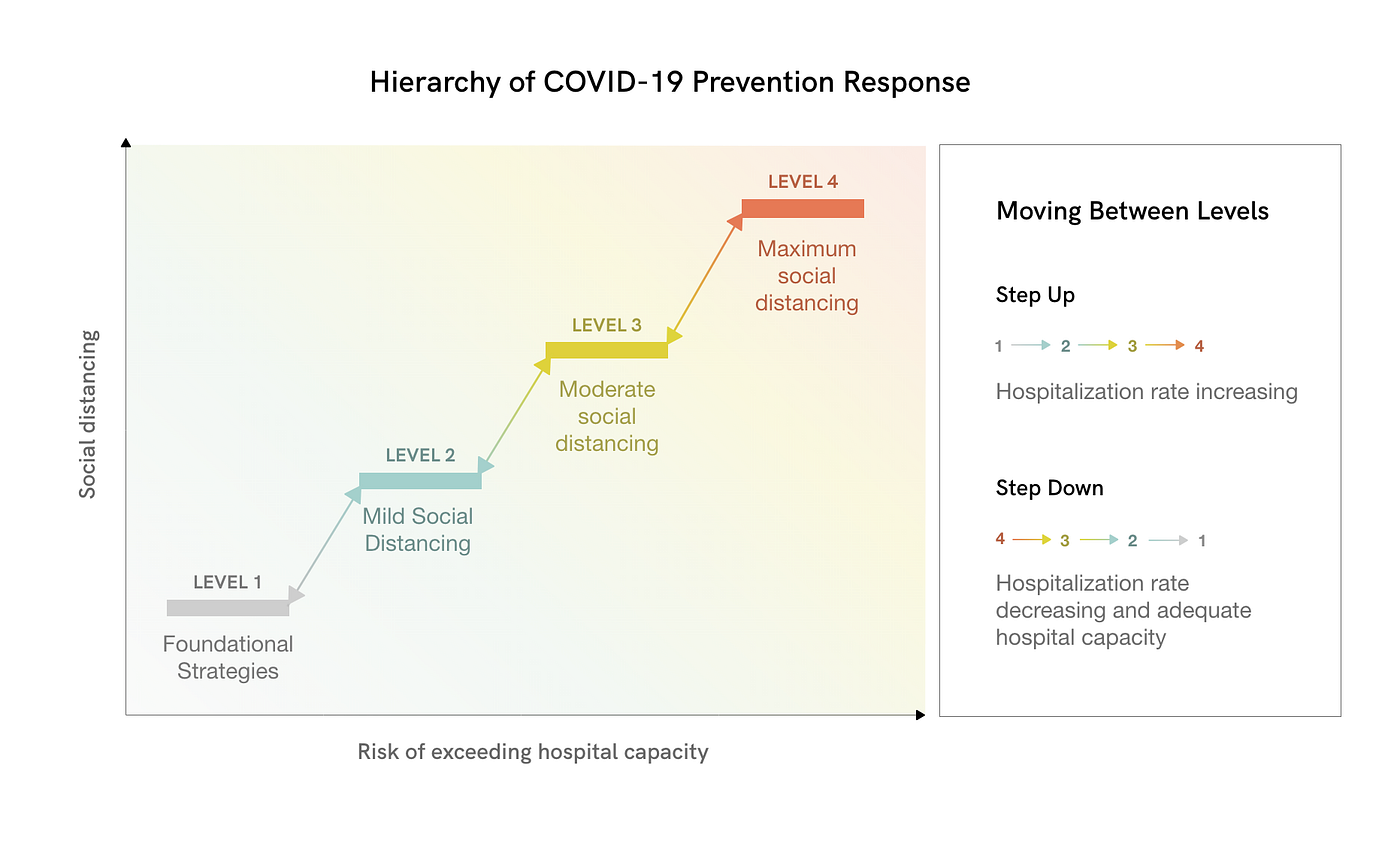

Second, we need to establish a hierarchy of public health interventions to reduce Covid-19 transmission. The foundation of this hierarchy should include strategies to promptly identify infected individuals and to protect those most vulnerable to poor outcomes. We have proposed four levels of action below with progressive intensities of interventions in the higher levels. Strategies that are the least socially disruptive can be placed in the lowest level; ultimate stay-at-home orders that restrict personal movement can be reserved for the highest level.

Third, we need a data-driven approach to move between those levels of action. We propose changing levels based on the daily rate of new hospitalized cases and our hospital capacity to manage Covid-19. When more reliable, we can use infection prevalence data from testing as another barometer to calibrate our actions.

Fourth, we need to rapidly augment our public health infrastructure, in particular our capacities for expanded testing and reporting but also for monitoring the disease in the population and for rapid investigations of disease outbreaks in places like nursing homes, homeless shelters, and essential businesses. We will need several new policies to support adherence to isolation requirements, like paid sick leave, and new infrastructure, like temporary accommodations for those that live with members of vulnerable groups.

Other countries have made extensive use of technology for checking in with people who require isolation and for automating contact notification. We may benefit by similarly applying private information technology to notify people of their test results and those who have been in contact with them.

Finally, we need to consider the inadvertent consequences of our actions in responding to Covid-19, including deferred health care, long-term unemployment, educational inequities, and social isolation. Policymakers should address some of those now. Our current decision-making structure should include a calculus for balancing the effects of Covid-19 on health and health care systems with other social objectives.

Foundational strategies for controlling Covid-19

We consider the following to be the most impactful strategies for controlling Covid-19; all of them should be implemented now and continued until a viable mass vaccination program is available or there’s evidence the disease is no longer a public health problem.

- Promote hygiene practices as universal social norms, including those for regular handwashing and alternatives to traditional greetings like handshakes or embraces. Place hygiene facilities at the entry to all public spaces, including retail facilities, businesses, places of congregation, schools, and public transportation. Expect individuals with respiratory infection symptoms to wear face masks whenever they need to be in shared spaces.

- Advise those at higher risk for severe illness, including the elderly and those with chronic diseases, to limit their contacts. Provide needed emotional and material support to these individuals

- Implement universal screenings (e.g., temperature, fever, symptoms) at places with vulnerable populations, including hospitals, medical clinics, skilled-nursing facilities, assisted living, senior living, homeless shelters, jails, detention facilities, and group homes. Those facilities should also have access to rapid-turnaround testing and facilities for employee screening and physical segregation of Covid-19-positive individuals.

- Provide publicly funded access to prompt testing without a physician’s order and without a fee for all individuals who are symptomatic. Create testing capacity at standing community sites (e.g., fire stations). Offer home-based self-collection of test specimens when validated and FDA authorized. Obtain information from individuals at the time of testing that includes identification, address, contact, symptoms, employer, and recent close contacts. Notify individuals of test results and mandatory isolation requirements digitally or where needed via telephone.

- Conduct individual clinical follow-up (e.g., daily symptom checks) for those with confirmed Covid-19 and who show moderate to severe symptoms. Provide this as a public service for those without reliable access to health care.

- Provide digital tools for those infected with Covid-19 to quickly notify their workplaces, schools, and close contacts.

- Support isolation requirements by providing, as needed, public isolation facilities for those without alternatives, paid leave from work, food resources, and other basic human needs.

- Promptly initiate investigations of cases and clusters of Covid-19 at vulnerable population facilities (e.g., hospitals, congregate living facilities, essential businesses) and implement controls.

Levels of action

A hierarchy of levels of action should include the above foundational strategies as well as progressive tiers of disease control interventions.

Level 1: Foundational strategies

- Universal hygiene practices

- Testing, isolation, contact notification, and clinical follow-up

- Guidance and support for limiting contacts for those at high risk for severe illness

- Symptom screening in high-risk facilities

- Rapid case and cluster investigations in high-risk environments

Level 2: Mild restrictions on person-to-person contact and enhanced screening

- All of the above and these:

- Prohibit mass gatherings (e.g, indoor professional sporting events, professional conferences, religious services, indoor music events)

- Encourage telework, telelearning, and telehealth for all businesses and organizations

- Institute occupancy reductions for public or private venues (e.g., shops, restaurants, bars, gyms, museums, libraries)

- Close facilities with vulnerable populations to nonessential staff and visitors

- Screen employees and staff of congregate living settings

Level 3: Moderate restrictions on person-to-person contact

- All of the above and these:

- Limit gathering size (less than 50 people)

- Require telework, telelearning, and telehealth

- Close public and private venues (e.g., shops, restaurants, bars, gyms, museums, libraries); food takeout or delivery exempted

Level 4: Maximum restrictions on person-to-person contact

- All of the above and these:

- Close businesses except those that provide essential services

- Stay-at-home advisory

A data-driven approach for moving between levels of action

Staying in balance means being focused on a singular aim — keeping hospitals above water. We can titrate policies to hospital admission rates and local carrying capacity for Covid-19 care, for example dedicating 50% of acute care beds. Leading indicators like daily case rates and emergency room visits can now be correlated with hospital admission rates to provide an early warning system. Increased testing and contact tracing is essential for high risk populations and caregivers, but achieving our primary goal does not require universal testing and contact tracing in all places before titrating our responses.

We propose two measures for stepping down from our current state of maximum restrictions.

- First measure: Consider the actual rate of change of hospital admission rates for Covid-19 in a geographical area over a period of 14 days. We propose hospitalization rates because individuals with Covid-19 requiring hospital care are more completely counted than those with less severe symptoms and because hospitalization rates more precisely reflect the burden of disease that society is working to manage. Because the average time it takes to spread infection from one case to the next is three to five days, 14 days represents at least twice that interval.

- Second measure: Consider the relationship between the area’s hospital admissions for Covid-19 and its hospital capacity available for treating the virus. This measure recognizes that hospital capacity available for Covid-19 can vary and will depend on overall bed capacity per person in the area’s population, the bed capacity needed for other acute care conditions, and steps hospitals can take to increase capacity for Covid-19 care (e.g., canceling elective admissions, utilizing surge capacities).

We propose the following guidelines for whether to step up or down among levels of action. When more reliable, we can use infection prevalence data from testing as another barometer to calibrate our actions.

- Step down: An area can step down to a lower level of action when area daily hospital admission rates for Covid-19 are stable or declining for 14 days and hospital admissions for the virus are below the area’s capacity to deliver care (e.g. no more than 50% of bed capacity devoted to Covid-19).

- Step up: An area can step up to a higher level of action either when hospitals are over capacity with their ability to deliver care for Covid-19 or when either daily hospitalization rate trends or daily case rates and emergency room visits predict that hospitals will be over their capacity to deliver care.

In many regions, officials have been using predictive models to make decisions on social distancing measures. Models can be helpful to compare differences between alternative strategies and to show a range of possible outcomes, but their projections can change radically based on the inputs chosen. Given the uncertainties about the behavior of Covid-19, we propose using actual observed data on new hospitalizations and hospital capacity in order to determine a level of response.

The approach selected for moving between levels of action must be communicated to the public in advance of implementing it. To reinforce predictability, government officials should consider providing a weekly update on the current regional situation along with the level of action required along with visual tools to demonstrate reasoning.

Urgently needed public health infrastructure and capacities

To implement the hierarchy we’ve laid out, California will need to rapidly assess its readiness for such a plan and build public health infrastructure. While it will take time to achieve all of these goals, we can start immediately with some tactics:

1. Publicly publish real-time metrics needed to inform responses at state and county levels. The state should improve communicable disease data reporting systems and information reporting requirements to meet this need. Metrics on the public dashboard should include these figures:

- Daily number of Covid-19 tests and positive results by date of symptom onset reported by age, gender, ethnicity, and zip code/census tract

- Daily number of new Covid-19 hospital admissions and discharges reported by age, gender, ethnicity, and comorbidities

- Daily number of Covid-19 ICU admissions/discharges reported by age, gender, ethnicity, key comorbidities, and intubation status

- Daily available hospital acute care and ICU bed capacity

- Estimated Covid-19 population-based incidence rate

- Estimated Covid-19 prevalence (when testing for immunity is available)

2. Ensure adequate state, regional, and county laboratory capacity for testing needs. We need to increase laboratory capacity for high-volume, high-throughput molecular testing, including self and home specimen collection. We also need to validate immunological testing (testing for antibodies that could show prior infection status and immunity).

3. Establish a state program for on-demand community testing, providing testing and results by digital appointment without a fee at state or county designated facilities. This program should include follow up with individuals who test positive for Covid-19 to ensure safety and support of isolation as well as digital means to notify close contacts and employers.

4. In addition to testing people with symptoms, establish a state program for testing random samples of the population for Covid-19 to know how widespread infection is and how many people have already been infected.

5. Develop local protocols and capacity for rapid case and cluster investigation, create and maintain regional predictive models for Covid-19-related hospital demand, and establish disease prevention and social distancing guidelines for operating businesses and organizations (or adopt Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance).

Enabling state-level policy changes

In addition to building the above public health capacities, California needs to consider and adopt state-level policies to support people’s need to isolate and mitigate the economic impacts of the epidemic. Additional state-level policies may be needed to ensure the implementation of the Covid-19 response does not have disproportionate negative repercussions on poor and vulnerable populations. Enabling policies could include these:

- Mandating paid sick (and family) leave or an alternative mechanism (e.g., state disability insurance) for all workers’ testing, recovery, and any required isolation

- Prohibiting discrimination or adverse employment action as a result of Covid-19 status or vulnerability

- Prohibiting eviction of anyone with Covid-19 or of workers caring for individuals with Covid-19

- Supporting the income of and providing food to those unable to work under social distancing policies and not otherwise covered by federal and state income support policies

- Legislating return-to-work standards for employers

- Establishing legal standards for the collection, sharing, and retention of information related to an individual’s Covid-19 infection or immune status

- Establishing a state list of essential businesses and services

- Mandating the state to create a real-time dashboard that displays regional and state metrics for Covid-19

Uncertainties

We recognize that our knowledge of Covid-19 as a scientific and medical community is incomplete. For example, we do not yet know precisely how many cases are asymptomatic and what fraction of the infected are diagnosed. Many of the uncertainties will be answered in time and with experience. We propose this approach with humility as one contribution to a vital public conversation.

Reviewers

Suzanne Bohan, Jean Fraser, Stephanie Strathdee, Jeff Martin, Jason Corburn, Fernando Otaiza, Vincent Lafronza, Jake Sonnenberg, James C. Dickerson, and Joseph A. Ladopo

Illustrations

Marisa Asari (illustrations); Vichanon Chaimsuk & Adrien Coquet (NOUN project icons)

References

Anderson, R., Heesterbeek, H., Klinkenberg, D., et al. “How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic?” The Lancet. 395(10228): 931–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5.

Boccia, S., Ricciardi, W., Ioannidis, J. 2020. “What Other Countries Can Learn From Italy During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” JAMA Internal Medicine. Published online 7 April 2020. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1447.

Burke, R.M., Midgley, C.M., Dratch, A., et al. 2020. “Active Monitoring of Persons Exposed to Patients With Confirmed COVID-19 — United States, January-February 2020.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69(9): 245–246. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6909e1.

Burstein, R., Hu, H., Thakkar, N., Schroeder, A., Farmulare, M., Klein, D. 2020. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 Policy Changes in the Greater Seattle Area Using Mobility Data. IDM. Published online 29 March 2020. https://covid.idmod.org/data/Understanding_impact_of_COVID_policy_change_Seattle.pdf.

Dalton, C., Corbett, S., Katelaris, A. 2020. “Pre-Emptive Low Cost Social Distancing and Enhanced Hygiene Implemented Before Local COVID-19 Transmission Could Decrease the Number and Severity of Cases.” The Medical Journal of Australia. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3549276.

Ferguson, N., Laydon, D., Nedjati Gilani, G., et al. 2020. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College London. https://doi.org/10.25561/77482.

Giesse, J. (2017). Modern Infectious Disease Epidemiology. (3rd ed.) CRC Press.

Gottlieb, S., Rivers, C., McClellan, M., Silvis, L., Watson, C. National Coronavirus Response: A Road Map to Reopening. American Enterprise Institute. 29 March 2020. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/national-coronavirus-response-a-road-map-to-reopening/.

Hellewell, J., Abbott, S., Gimma, A., et al. 2020. “Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts.” The Lancet Global Health. 8(4): e488–e496. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7.

Kucharski, A., Russell, T., Diamond, C., et al. 2020. “Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: A mathematical modelling study.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Published online 11 March 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30144-4.

Lauer, S., Grantz, K., Bi, Q., et al. 2020. “The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application.” Annals of Internal Medicine. Published online 10 March 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-0504.

Li, Q., Guan, X., Wu, P., et al. 2020. “Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia.” The New England Journal of Medicine. 382(13): 1199–1207. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

Lin, C., Braund, W., Auerbach, J., et al. 2020. “Policy Decisions and Use of Information Technology to Fight 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease, Taiwan.” Emerging Infectious Diseases. 26(7). https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200574.

Mizumoto, K., Kagaya, K., Zarebski, A., et al. 2020. “Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020.” Eurosurveillance. 25(10). https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180.

Moriarty, L., Plucinski, M., Marston, B., et al. 2020. “Public Health Responses to COVID- 19 Outbreaks on Cruise Ships — Worldwide, February-March 2020.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69(12): 347–352. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e3.

Pan, A., Liu, L., Wang, C., et al. 2020. “Association of Public Health Interventions With the Epidemiology of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China.” JAMA. Published online 10 April 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6130.

Qualls, N., Levitt, A., Kanade, N., et al. 2017. “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza — United States, 2017.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66, no. RR-1:1–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6601a1.

Russell, T., Hellewell, J., Jarvis, C., et al. 2020. “Estimating the infection and case fatality ratio for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) using age-adjusted data from the outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship, February 2020.” Eurosurveillance. 25(12). https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.12.2000256.

Salathe, M., Althaus, C., Neher, R., et al. 2020. “COVID-19 epidemic in Switzerland: on the importance of testing, contact tracing and isolation.” Swiss Medical Weekly. 150(20225). https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20225.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Pandemic Influenza Plan: 2017 Update. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/pan-flu-report-2017v2.pdf.

Verity, R., Okell, L., Dorigatti, I., et al. 2020. “Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Published online 30 March 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7.

Watson, C., Cicero, A., Blumenstock, J., et al. 2020. A National Plan to Enable Comprehensive COVID-19 Case Finding and Contact Tracing in the US. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Health Security. http://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/our-work/pubs_archive/pubs-pdfs/2020/a-national-plan-to-enable-comprehensive-COVID-19-case-finding-and-contact-tracing-in-the-US.pdf.

Xie, C., Lau, E., Yoshida, T., et al. 2020. “Detection of Influenza and other respiratory viruses in air sampled from a university campus: A longitudinal study.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 70(5): 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz296.