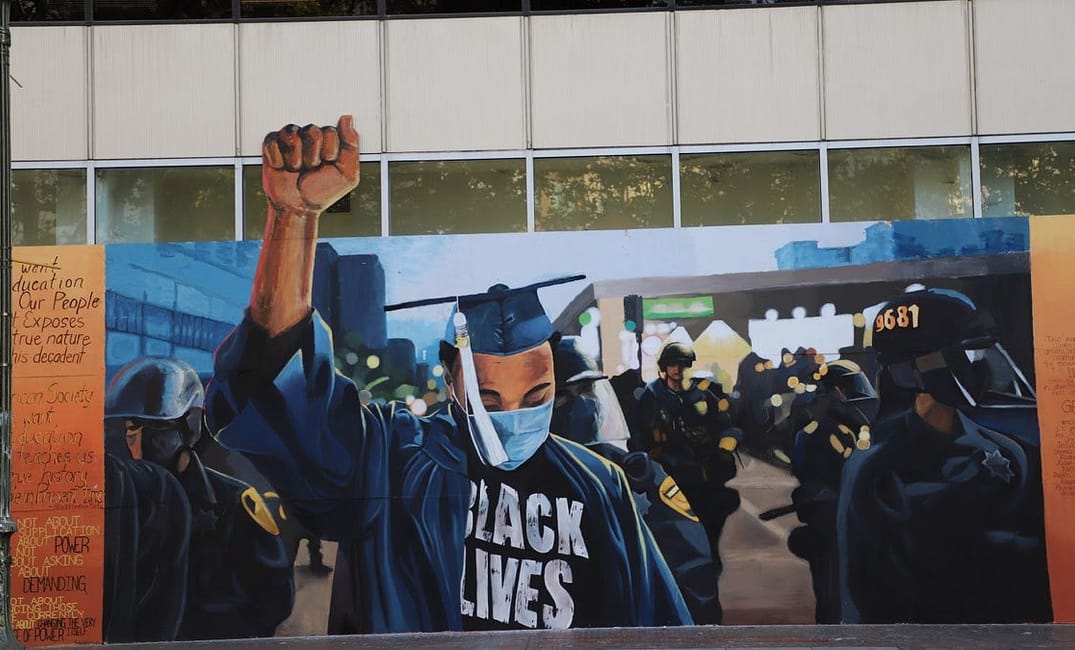

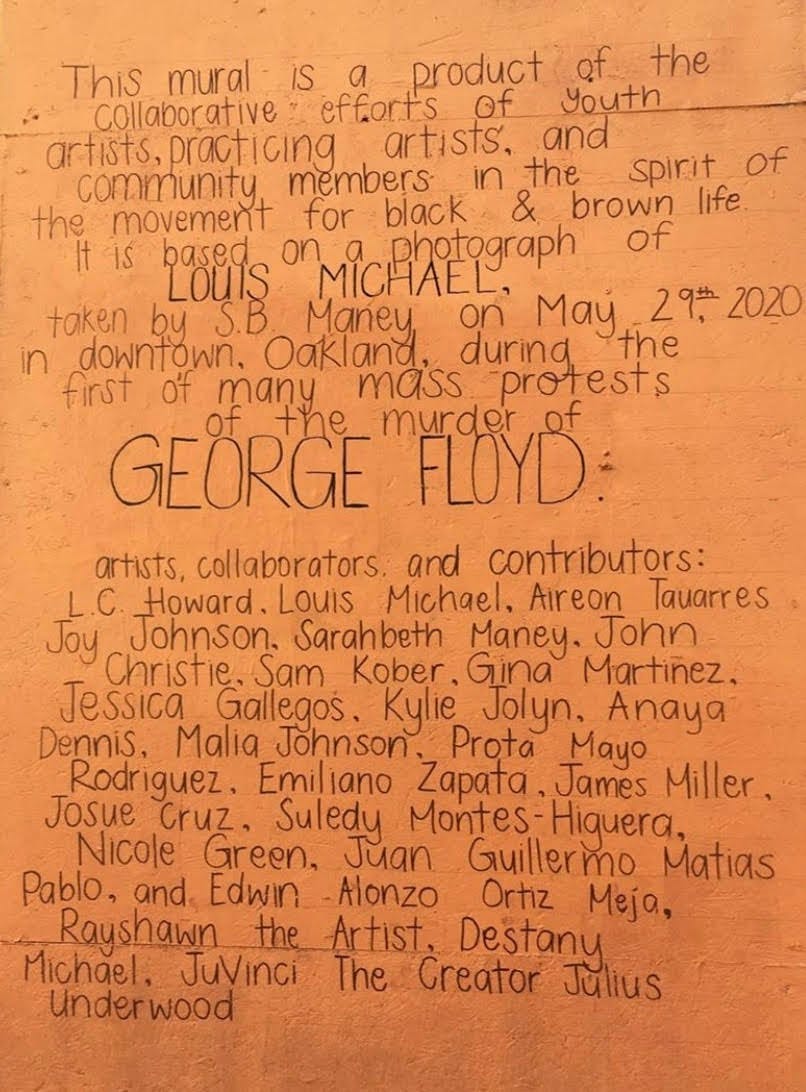

In Oakland, the revolution is being muralized. For weeks, local artists and activists have united in a takeover of Oakland’s downtown streets to deploy vibrantly-charged murals that encourage viewers to reimagine what safety in the community should look like.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that the East Bay’s hub — long known for a legacy of art and resistance — has taken center stage in the dismantling of police brutality, systemic injustice, and anti-Blackness.

In a city that already boasts over 1,000 murals, Oakland is a poetic location for these colorful acts of solidarity, which loudly declare: “WE GOT US.”

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

That said, this current wave of street art tidaling through the Town isn’t just some overnight sensation for Oaklanders. Activism is rooted here. Murals and art have long been a way to communicate resistance, struggle, joy, and solidarity.

The birth of a movement

Decades prior to these tragic and unnecessary deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor — whose murderers have still not been arrested — Oakland has been organizing for, fighting toward, and creating a world that reflects diversity, tolerance, and self-sufficiency for all members of society, particularly the most disenfranchised.

The origins of this city’s rebellious spirit go as far back as the 1960s, when Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party in West Oakland to defend the neighborhood against acts of rampant police terror and racial discrimination. The Panthers’ reputation quickly grew and came to symbolize the Black voice of resistance in America.

What most people don’t seem to know that the Panthers were more than a revolutionary group of fighters who implemented community programs for those in need — they were also a platform for emerging, visionary artists.

Dorothy Zellner, Ruth Howard, Lisa Lyons, and Mark Comfort are all unheralded figures who helped develop the famous logo for the Black Panther Party — a sleek, muscular, silhouetted panther on the attack. But they weren’t the only Black artists infusing their politics into art for this movement that was launched internationally from the Bay Area.

Emory Douglas, the Black Panther’s minister of culture, most famously helped to spread the Party’s ideals to a wider audience through his illustrations. His artwork was one of the most effective tools that the Black Panthers had in their arsenal — the ability to communicate identity and symbolism while building empathy in the form of public imagery.

Indeed, artists like Douglas have always been at the front lines of American activism because they possess that rare ability to bridge worlds; to fuse the past, present, and future by conceptualizing new realities; to speak in a universal language tongued in the shapes and colors of our deepest political, social, and human hopes; and to share that with outsiders.

Despite being tremendously talented, artists like Dorothy Zellner and Emory Douglas were rejected by institutional gatekeepers in the art scene. And even though Douglas attended City College of San Francisco and had established himself as a professional in his craft, his work was rarely welcomed into privately owned exhibition spaces. So, like many tremendous voices of the time who were Black, immigrant, female, poor, or otherwise excluded and marginalized, these artists eventually started painting where they could: in public streets.

The historical effects of gatekeeping and exclusion

It’s no coincidence that the same redlining and blockbusting tactics that were used to segregate and neglect Black and poor communities in the mid-20th century across America were philosophically implemented by art galleries to aggressively prevent artists of color from entering their halls, leaving them with few other options but to transform their own neighborhoods into museums of expression.

From the ’60s to the ’80s, graffiti was born from this systemic rejection, and openly challenged the status quo of Black erasure — in the Bay Area and elsewhere. Artists who had been otherwise alienated for years, and without proper means toward wider acceptance, began to convey their own political ideologies, community needs, and sense of self by spray painting in the most visible locations where the racist institution had no say. Corner stores, freeways, and other heavily trafficked places suddenly became bulletin boards for aerosol warriors whose artistic pursuits had been denied by the mainstream.

It wasn’t always a method welcomed by the public — often misrepresented as purely destructive or criminal — but this was the necessary emergence of street art, not only in Oakland and San Francisco but nationwide. It was social resistance disguised in spray paint, and it opened the doors of possibility for future artists to claim their political and social environments. Let’s be clear: These weren’t murals, but without this early stage of graffiti and grassroots rebellion, murals might have never gained the popularity and political edge that they now have today, and which are currently on full display in the modern context of Black Lives Matter.

I wish I could say that these artists — among so many others whose names have been lost to systemic exclusion — were recognized and embraced by those in positions of power in the art world. But they weren’t, not enough. Even today, there still aren’t always the same opportunities for Black artists as there are for their white or affluent counterparts — and even when they do receive work, they are often burned out by invisible labor and cultural misrepresentation.

This sort of double-standard mistreatment has not only continued but has exacerbated during the coronavirus, where the inequities and racial gaps in our country have been the most visibly exposed since the civil rights movement. But small changes are finally happening, thanks to our artists and activists. In Philadelphia, for example, the local government has acknowledged the reality of Black artists receiving less access to the city’s resources, and so created the Emergency Gap Fund to help sustain Black art, specifically during Covid.

Local artists creating solutions

Sadly, even though we like to herald ourselves as liberal progressives on the West Coast, statistical inequality and lack of opportunities for Black artists are not any better here in the Bay Area than in other parts of the country.

That’s where Natty comes in. He’s a Richmond-based artist who has been painting in Oakland and other cities throughout the United States, and who decided that he’d had enough. In 2015, he became the founder and executive director of the Bay Area Mural Program — one of the only Black-owned mural organizations in the Bay Area, whose efforts helped to orchestrate the now-viral Black Lives Matter message painted on 15th Street.

A longtime East Bay resident and Oakland-rooted artist, Natty explained his experience to me as a Black muralist in the Bay Area struggling to find work and representing his community — even in recent years — and how he sometimes found himself in uncomfortable positions dealing with gatekeepers.

“I won’t mention any names, but he’s an older white man who owns half of downtown,” he told me, recalling a time he’d painted the biggest mural of his career in a major East Bay city. “He came outside to see me working, and when he saw who I was, he told me straight up that he’s a racist, but as long as I did a good job, he’d be satisfied.”

Natty recalls how the other artists and organizers who were present were shocked at how openly the man — who owned the building Natty and his team had been commissioned to beautify — had been about his outdated politics. To his credit, Natty — a loving, gentle, and open-minded spirit — made a joke and finished his work. But he admits that it was in that moment he realized he never wanted himself, or any other artist in his position, to be in a powerless situation like that again.

Imagine being an artist who depends on jobs like this to make a living, then hearing your employer tell you he doesn’t agree with who you are as a person — merely because of your skin tone. Natty immediately tapped into his network — artists and organizers like REFA1 at Aerosoul, Derrick Scavhers from Kiss My Black Arts, and community activists with connections to the Black Panther Cubs — and realized that like them, he could start his own program to showcase Oakland’s Black talent in public spaces.

When thinking about the history of Oakland’s revolutionary ethos, you can’t remove the activism from the artwork. Oakland is publicly artistic because it is socially engaged, and it is socially engaged because it’s publicly artistic. Both elements combine to give the city its well-earned reputation, reflecting a unique blend of its history with its racial and political consciousness in a way very few cities I’ve lived in or visited can embody in an authentic way on a daily basis.

Natty’s Bay Area Mural Program is a perfect example of Oakland’s tradition of resistance and vocalizing change until it manifests through art. And though the organization is geared and equipped to be a voice for the Black community, they are also a group of artists who can paint flowers or sunshine, if that’s what’s needed.

“We don’t always want to be painting Black Lives Matter, but it’s a necessity,” Natty said. “It’s something that the community has been saying forever, since the days of the Black Panthers — just in different words. We want to paint other things, of course, but knowing that we have this platform and spotlight, we want to use it to do meaningful work until changes are made.”

Natty’s hope is becoming a reality, and it’s something we should celebrate and acknowledge as Bay Area residents — that a genuine voice from the community is creating a space for other voices to join in, and together they’re demanding to be heard.

From youth art education classes to public engagement partnerships to massive murals that span 130-by-40-feet and cover the entire flesh of a building, Natty’s dream has become more than he imagined — it has become everything that inspired him as an emerging artist coming up in the Oakland art scene.

“The activism is interwoven into the artwork and community for us,” he explained. “It’s not hidden. You can’t separate the art from the activism here. Many of these artists are involved in activist organizations or collectives. Many other cities have activists, and many other cities have artists, but very few have such a high percentage of overlap between activists who are also artists and how they both constantly inform each other here in Oakland.”

What is happening right now in Oakland is an extension of all these legacies, the overlapping textures of many decades’ worth of fighting, mobilizing, frustration, anger, love, and dreaming, and with the help of artists and community leaders like Natty, the rest of the world is beginning to see just how beautifully expressive Oakland’s soul is.

And for anyone refusing to see the soulful history right in front of them, Natty and his crew have helped by putting the message beneath everyone’s feet, and literally in our streets, too.

Unfortunately, not everyone wants to hear this important message. Just last week, a white man and woman painted over a Black Lives Matter street mural in Martinez, California, and allegedly pulled a gun on a BLM supporter on the outskirts of the Bay Area, reminding us that there there is still significant work that needs to be done in shifting the mindset of hateful citizens. We must deconstruct and dismantle the racially biased systems — from police oppression to media representation — that only create fear and division among Americans.

Murals are merely one tool for combating the negative imagery used in the mainstream to vilify Black lives, but we need to also use our political and civic voices to demand change until we see acts of hate like this punished at the judicial level.

Black Lives Matter is more than just art, and it is more than just activism. It is a dire reality affecting many lives in the real Oakland and beyond. Until we eradicate the hateful rhetoric and systemic inequities opposing the efforts of Black and other diverse voices in this country, groups like the Black Panthers and the Bay Area Mural Program will have every right and every reason to share their urgent messages — and we should be listening and doing our part to show support where we can.

For more information on how to connect with BAMP, hit up their website.