It’s where Allen Ginsberg loitered with Jack Kerouac while the Black Panthers had their meetings upstairs. It’s where the architects of the free-speech movement argued over coffee. It’s where the Telegraph Avenue streetkids in the photographs of Richard Misrach hung out. It was one of the great good places.

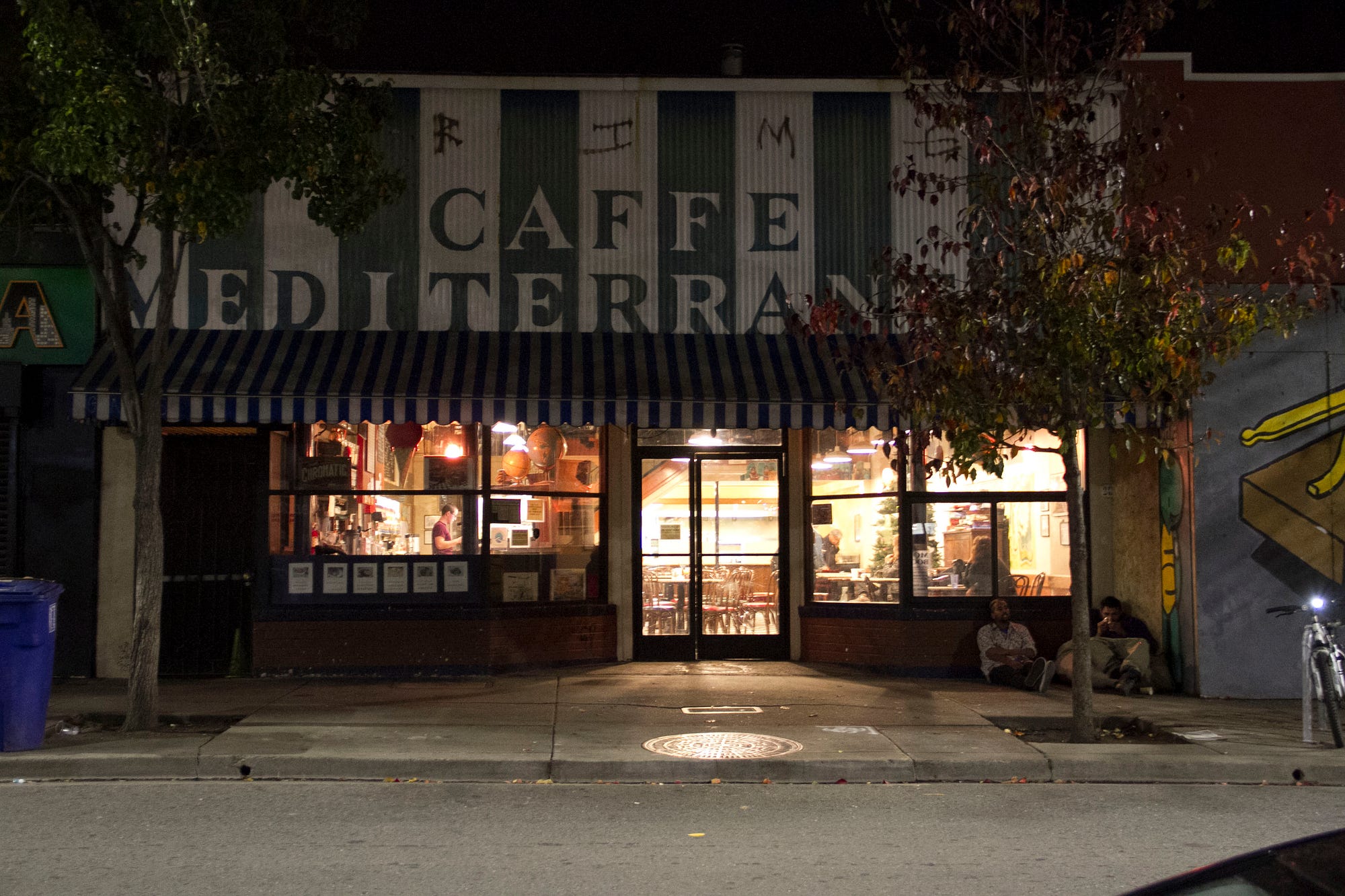

Caffe Mediterraneum — known to regulars as “the Med” — was the third- place anchor of Berkeley. Urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third place” to describe social spaces that are neither workplaces nor homes. They’re places where people are not required to be but which they seek out anyway—coffee shops, barbershops, bars, pharmacies, post offices, parks. For many Berkeley residents, that place was the Med.

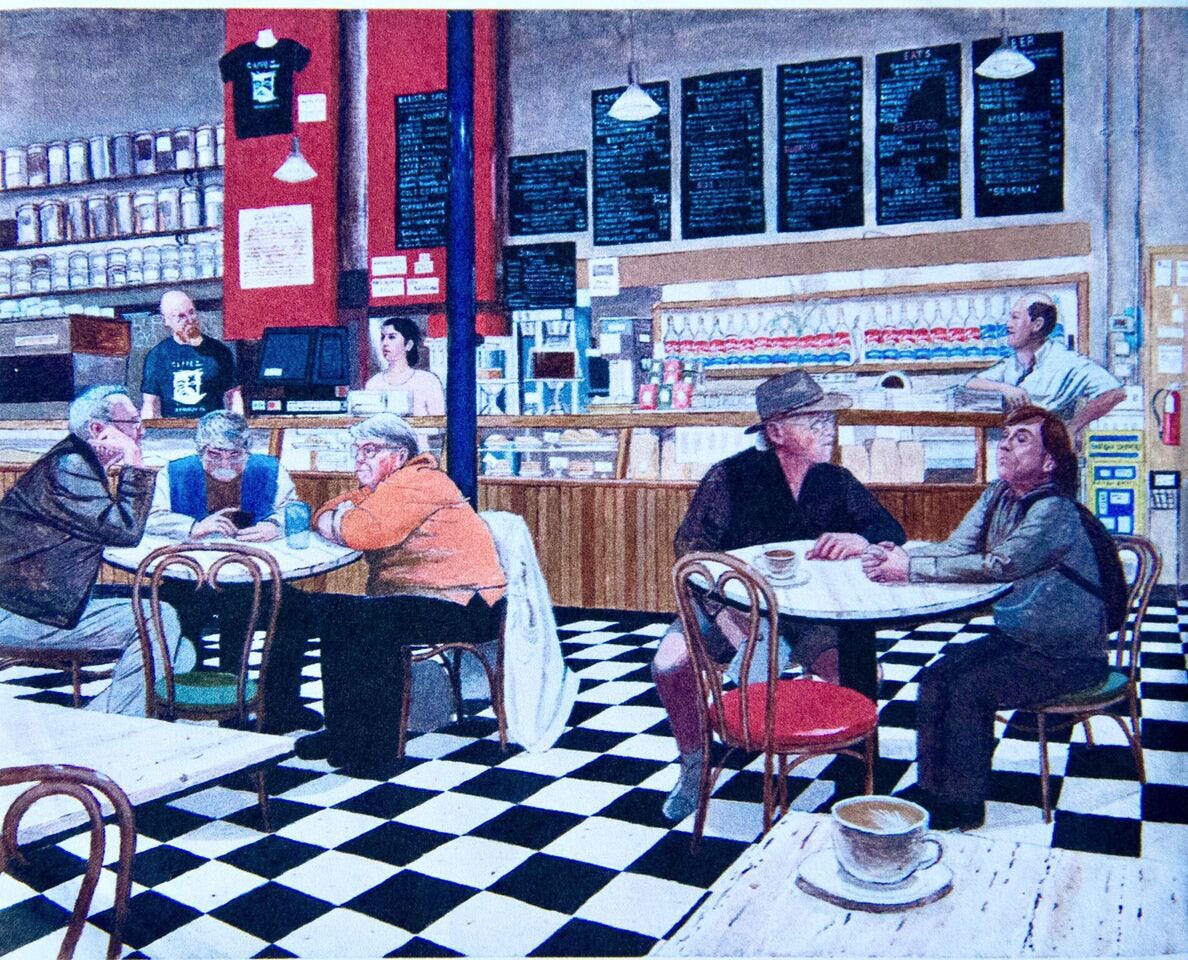

Marble tables, checker floors and cheap but good coffee served in bright, white cups. High ceilings and good light. Public radio, classy old guys up in the front. For me, Caffe Mediterraneum had all the necessary qualities of a third place. It seemed immune to bad days and heartache. I brought more first dates there than I can remember.

The Med was one of the few places in Berkeley that stayed open past 9:00 — a good place if you like books and beer but don’t want to read in a bar. I had gone there on a Monday night and learned of the coming closure only minutes after the news had been announced.

It felt like I’d walked in on a wake. The crowd went through the first four stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining and depression. Acceptance was yet a long way off. The death of Mother Theresa could scarcely have been greeted with greater displays of sorrow.

Some people cried. Others drank. A woman stood and sang an aria of mourning. (“Allow that I weep,” the first line translates.) I finally spoke to and learned the name of a man I’d been sitting next to for years (Nate). It was like the deck of the sinking Titanic. I wanted to say, “I love you,” to everyone.

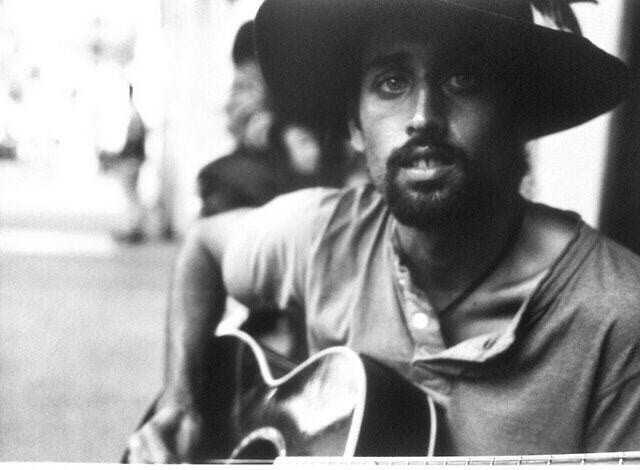

By Tuesday the grief of the previous night had quieted back to a dull roar. I had gone back with a notepad and a camera. I was seized with the urge to document, to record as much as I could before it all went away. This was familiar ground, but coming in this way, I felt less like a documentarian than a missionary, pursuing the local population with a kind of predatory curiosity.

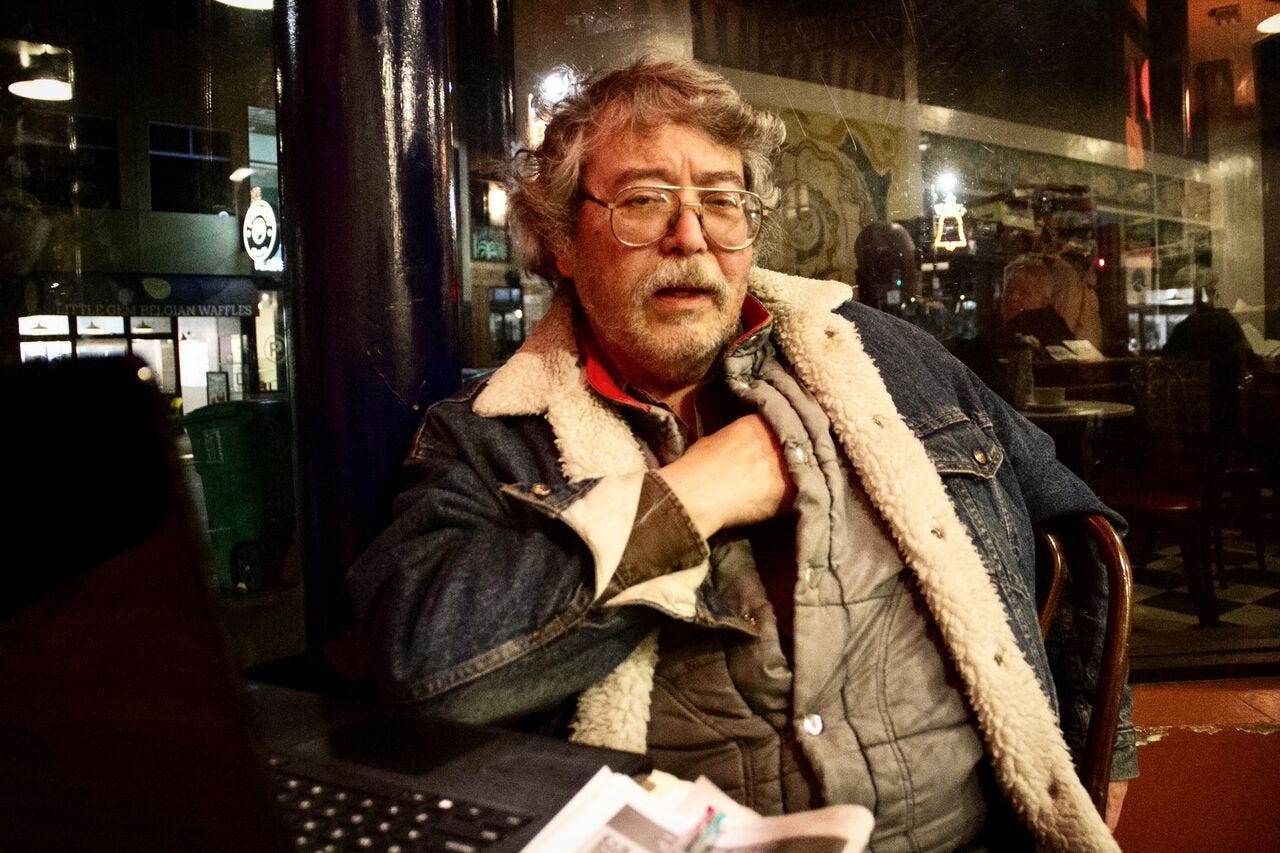

As I entered, I recognized the man seated at the bay-window table as one of those familiar strangers I’d seen but never talked to. Old-timers are the indicator species of a third place. The more of them who are gathered and the higher their median age, the better a place is likely to be.

Over all the time I’d been going to the Med, I hardly ever spoke to any of the classy old guys — and gals — who hung out there, the ones who, for me, were part of what made the place great. I could identify probably 15 faces that returned again and again, all between the ages of 50 and 80, but I didn’t know any of them.

I introduced myself to the man seated in the window, who told me his name was Jos Polman and that he had been born in Indonesia, grew up in Holland and moved to Berkeley as a student in the late ’60s.

“I don’t know that you would call me a regular,” Jos said. “I’ve only been coming here for the last eight or nine years.”

I asked what had drawn him to the Med to begin with and why he keeps coming back. He explained that he used to get coffee at Bongo Burger, but this place was a little closer and a little cheaper. His answers were all those of utility, and his attitudes decidedly unsentimental.

“There’s this air of—how shall I put it?” he said. “It’s a den of dysfunction. Remnants of old and, I think, worn-out Leftists sentiment. There are people here who are Marxists, Maoists and some anarchists. Those days are gone. It’s not the ’60s any more.”

“Of course,” he continued, “with the Trump win, we’re all in a state of shock, but I bet it’s not as bad as they think.”

I asked him what he would do when it closed.

“I won’t waste my time here anymore,” he said. “I’ll probably start fixing up my house.”

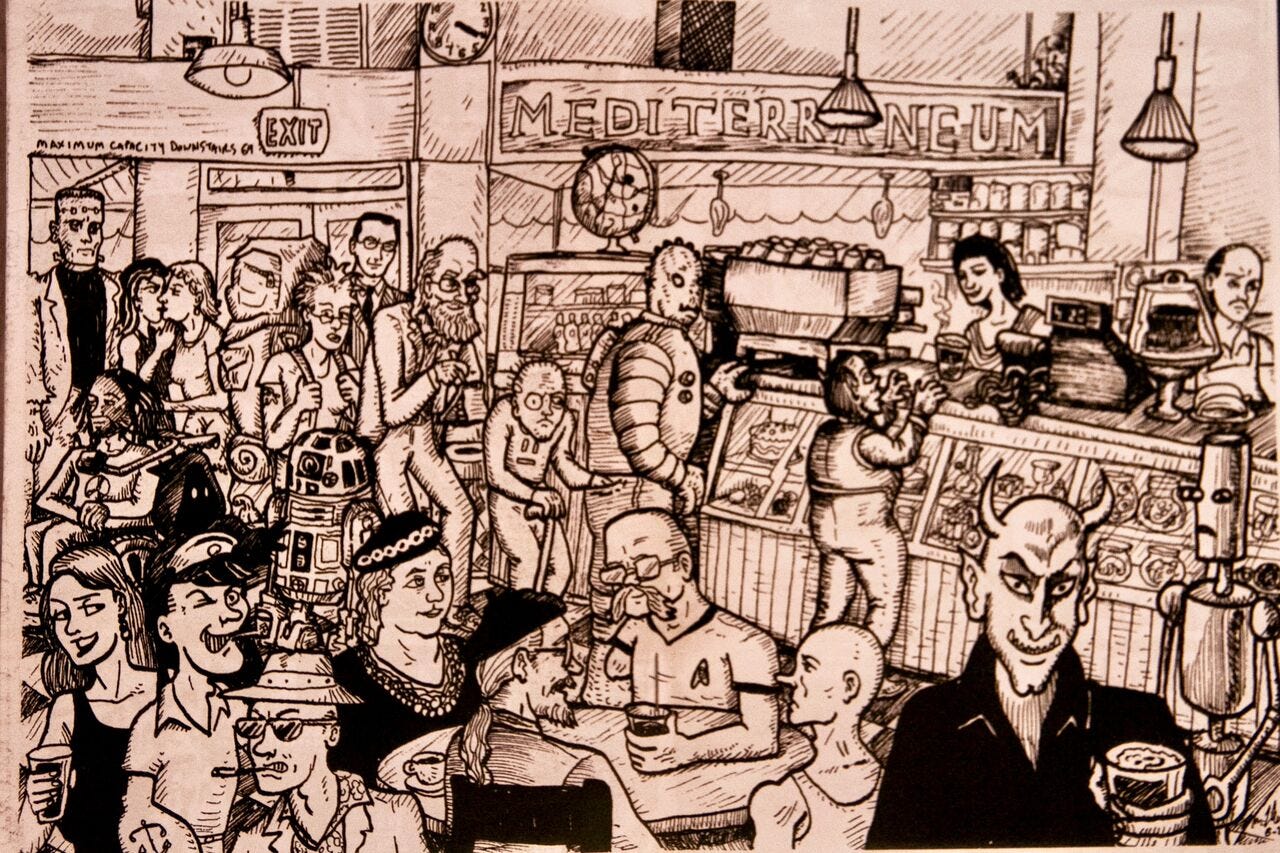

“You know, if you want to know more about the Med,” he said, “you should get your hands on the Medatrocity. It’s an illustrated book. This woman who used to work here made it. If you can get your hands on that, then you’ll know more about the Med than anyone. It’s just amazing. Just amazing.”

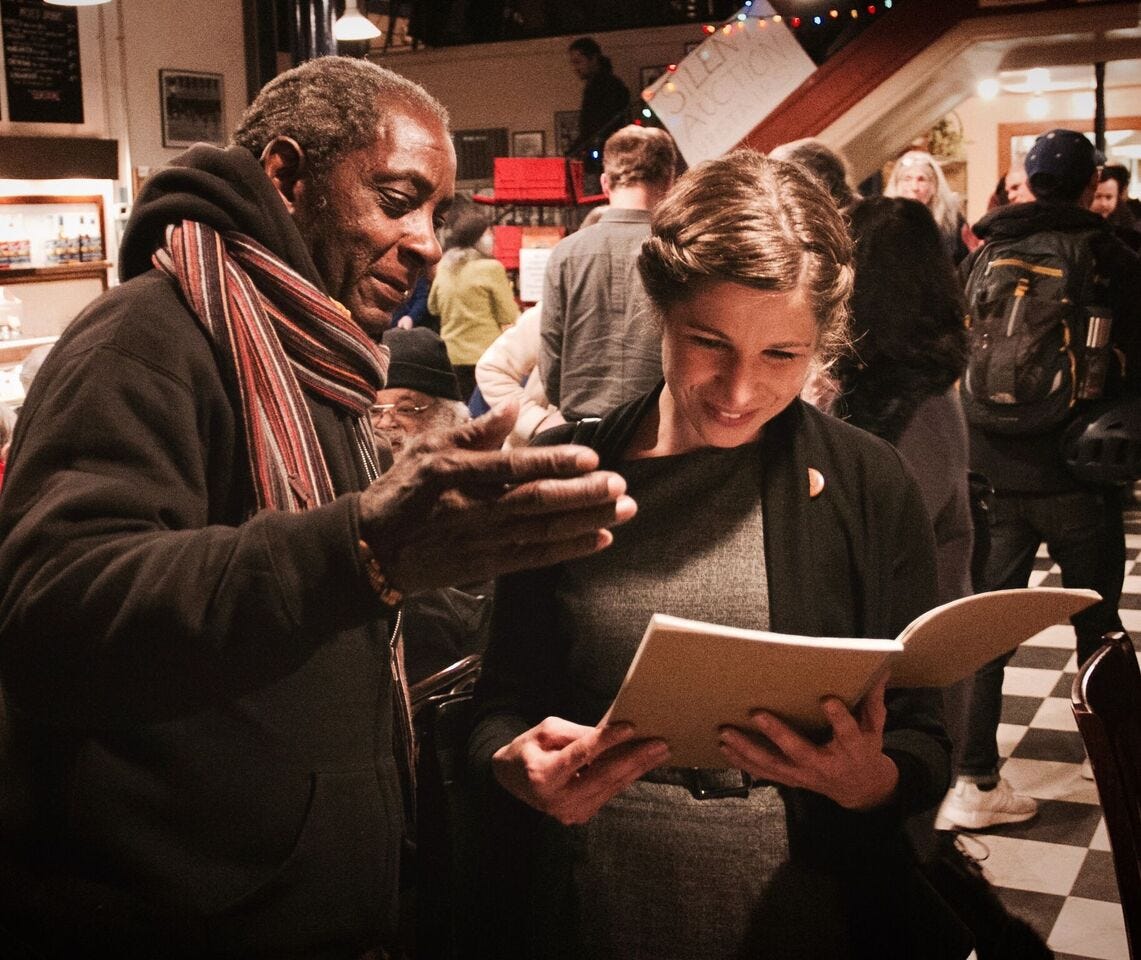

As we were talking, one of the other regulars came in and took a table in the back. “That’s Paul,” Jos said, and indicated that he was a regular worth talking to, and we relocated to join him.

Paul Kealoha-Blake had been coming to the Med on and off for 30 years. He has an impressive activist CV: He ran the East Bay Media Center for 25 years, serves on the Berkeley Mental Health Commission and the Police Review Commission, and, as a native Hawaiian, is a local advocate for island politics. On the Med billboard, the postings for rallies in defense of Mauna Kea were all Paul’s doing. Almost the entire time we talked, he kept his eyes on the police updates for Berkeley and Oakland — his face serious, downcast, bathed jellyfish blue in the glow of his phone.

Paul self-describes in ways that map neatly onto Jos’s caricature. “My views are extreme Leftist. Actually I would say Communist,” he said, laughing. “I came to the Med because of politics. It felt like a good fit and exactly that kind of environment of awareness and conversation that I was looking for.”

“I suffer from OCD,” he says. He pointed to the billboard across from us. “And it’s so appealing to organize that board. In fact, what am I going to do when that board is gone?” he said, and laughed again. Paul has the optimism of the narrowly defeated and a smile like FDR. It says both, “The sun’ll come out” and “I’m counting on your support this November.” He was already scouting for the next win.

“I’m looking across the street,” he said. “There’s a space for rent in the Center for Anachronistic Media,” he said, referencing the book and record store that had recently opened across the street.

“It’s 2,000 square feet,” he said, “which is plenty of space for something like this. It’s the people that make the Med. All we need is space. Same chemistry, just in a different test tube. Would you have any interest in going in on anything like that?” he asked, turning to Jos.

“Absolutely not,” Jos said.

Paul turned back to me. “I want to find out the details of what kind of place it’s going to be in there. Learn about the lease.” He has fantasies about the space, and in this particular one, Paul or someone like him takes it over, makes cheap coffee, sets out tables and puts up a billboard.

“The more I see it in my mind, the better it’s going to be,” he said.

Over the course of the following nights, I got to know more of the regulars, sit with them, eavesdrop and take photos. I became Dian Fossey scribbling observations on silverback males. I hadn’t noticed till then just how much of an old boy’s club the Med had been, but probably around 70% of the nighttime crowd were men, half of them over 50.

The following Monday was tango night at the Med. An elderly gentleman from Argentina raised himself up by the piano and wailed with such emotion he omitted the consonants.

In the back, the old-timers gathered. Paul, Jos and others besides. The atmosphere had taken on the tone and urgency of a field campaign. They debated the merits of rival locations and discussed the tactics of relocation. The singer carried on and on, and the regulars quieted their tone. They do not like tango night — they find the instructor presumptuous and the canned music asinine — but they respect the passion of the Argentinian.

“It’s a shitty use of the third-to-last night,” Steven Leach said, glaring. Steve is not one of the old-timers. He’s a member of the staff, but his sympathies are more with the group than the management.

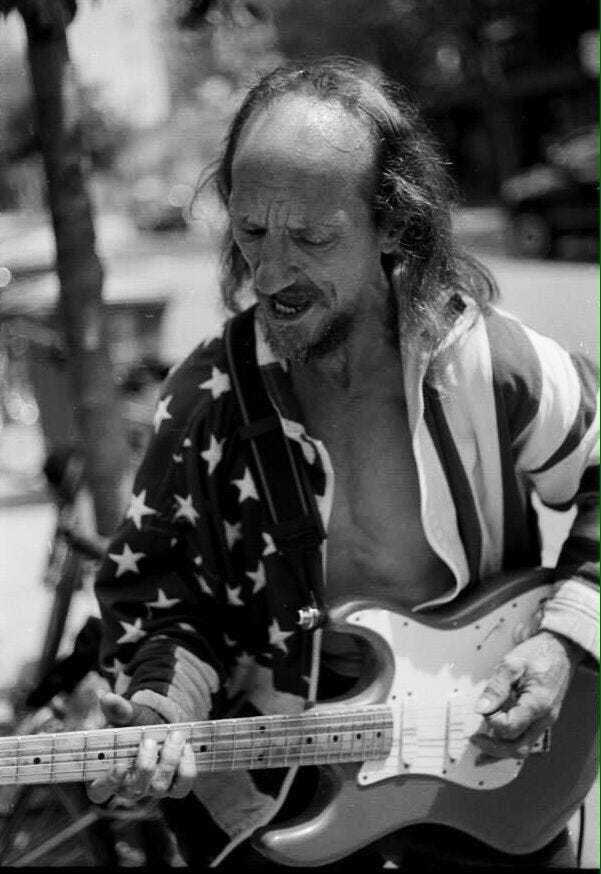

“Look, what are you gonna do in another week?” Ed Monroe asked and knocked his knuckles on the table. Monroe is a street artist. On weekends he sells paintings at the corner of Telegraph Avenue and Bancroft Way. He’s an admirer of Shakespeare, and talking with him to enter into not so much a conversation as a monologue. He enjoys an audience.

“We’re going to disband in four days.” Monroe spread the fingers of his hands and told about all the qualities that will be gone. “We need table hopping. An atmosphere like Caffe Trieste,” he said, leaning in. “And personally, I can’t concentrate unless a lunatic is raving at me from a few seats away. The laxity and 86’ing of common decency is something I look forward to in coming here.”

Monroe cast a look at me. In these few short days, I’ve become the designated anthropologist. But I’d forgotten my notepad and had to excuse myself to go upstairs to tear the title pages out of the pulp romance novels of the book exchange.

As I come back clutching a few ragged pages, Monroe addressed me directly.

“They used to call that place up front the Fishbowl,” Monroe said gesturing toward the table by the front bay window.

“Don Clausen was the center of everything there. He was the senior artist of Berkeley, you might say, kind of like how some folks might say now that I’m the old artist of Berkeley,” he said a muffled snort. “But I wouldn’t say that.” He caught and covered his vanity. “And he would just hold court there.”

Monroe launched into a Homeric inventory of every old regular he could remember.

“There was Ole Nielsen, the Swede,” Monroe said. “There was Bob Anderson, who owned the Albatross. Marten Metal—M-E-T-A-L—he was a metal sculptor—that’s why the name.

“You know who else? It’s probably important to include David Bradley, the son of Marion Zimmer Bradley,” Monroe went on. “She wrote The Mists of Avalon. I should name some women. There’s Julia Vinograd—she still comes here—and Alta and Lois Fisher. And Sami—she was a barista here but lives in Prague now.”

“She’s the one who wrote the Medatrocity,” Jos said. It was his only contribution to the conversation before Monroe belted on.

“Smartest mother-fucking people I knew,” Monroe said, nearly bellowing. “They accepted me, and I’m an idiot. The people I hung out with—that I hang out with—they’re extreme. And if you don’t pay attention, you miss the most important things.”

Telegraph Avenue has been in flux (some might say decline) for decades as long-standing businesses capitulate to fast-food eateries and chain retail. The biggest blow was probably when Cody’s Books closed.

Cody’s Books — along with Moe’s Books, Shakespeare & Co, and Black Oak Books — was a core member of the group of independent booksellers clustered around the north end of Telegraph. Alice Walker, Salman Rushdie, Maurice Sendak and Norman Mailer, among others, all did readings at Cody’s. During the tumult of the ’60s and early ’70s, the store served as a shelter and first-aid station for anti-Vietnam protesters. Its closure in 2006 was widely perceived as the beginning of the end for the avenue’s local and independent businesses. And of the four major bookstores formerly located on and around Telegraph, only Moe’s survives.

Some places become allied with a neighborhood’s identity and treated with the same reverence as a city park, even though as a private enterprise they are still subject to the market. Recognizing this, San Francisco adopted measures to support legacy businesses in 2015, though Berkeley has no such legislation.

Back in the café, the conversation returned to the topic of closure. There’s mixed sentiment toward Craig Becker, the owner. Craig had been decent to the business, more often behind the counter than in the back room. Since buying the place in 2004, Craig actively safeguarded the character of the Med. He has chased down and apprehended thieves and on more than one occasion defended the tip jar with his fists. He’s generally (though not universally) liked.

Craig also owned the building where the Med was located and put the place up for lease in 2014. His reasons for selling are simple: 12 years is long enough, and he’d like to do something else.

“Craig kept this place going for 12 years,” Monroe said. He respects Craig. “He brought in a lot of new customers — young folks, students.”

“This place survived in spite of Craig, not because of him,” said Steve. “You look at the Yelp reviews for this place, and what do they all say?Dirty, unsanitary, poor service.”

For me the grit was part of the charm. The cracked and peeling paint, the broken tabletops and the aromas of bacon, coffee and unwashed bodies. The graffitied-over doorframes and the handles held together with gaffer’s tape. The way the place stank like wet dog on rainy days and Burner crotch on hot ones. It all made you feel like you were in the scene, that you were part of some wonderful secret—that if something broke on you, or broke you, that it was somehow OK.There was a story happening all around, even if it wasn’t about you. This was what Berkeley smelled like. If you wanted sterile, there was a Peet’s one block over.

“A lot of other people, this is their home,” Steve continued. “Their office, their workspace, their study hall. Where are they going to go?” Steve had been living in the same parking space behind the Med for four months now. His concerns for the customers were the same for himself.

The Argentinean was still making the sounds of elongated vowels. A collection of stapled papers dropped in front of me. The Meditrocity. Jos snuck away during Monroe’s recollection and came back with a copy. The book stayed just long enough for me to take a single photograph, to verify its existence, before it was swept away again like H.P. Lovecraft’s Necronomicon.

Two nights later, the Med closed. Writers who went on to win the National Book Award did their work at this place, and now I have to write a eulogy. But I’m forgetting details. I’m forgetting people. I’m doing what I can, but it’s like going at the ocean with a butterfly net. The really big fish are never going to fit.

I’ve barely even mentioned the staff. There’s Charlotte, who kept directing me to talk to someone else (“They’ve got better stories”). Rejilio, who worked in the back for nearly 50 years. Concha, her hair in flares of violet. Abigail, who passed me forgotten umbrellas when it rained. And Craig, the owner, who had too many things to deal with in the closing that he could never sit still for questions. All I can do now is name them and give a detail, like Monroe’s epic list.

The Med is gone. I already miss the two-dollar coffee and the six-dollar burritos. I miss the checkered tiles and marble tabletops. I miss the street kids hanging out upstairs. I miss playing guessing games with the clientele — homeless or hipster? Postdoc or panhandler? I even miss the smell.

Nostalgia is a form of regret. And in looking over my notes, I regret that I never sat to talk with Julia Vinograd, the poet laureate of Telegraph Avenue. She had been a fixture of the Caffe’s front crowd for decades. (A youthful caricature of Julia appears on the front of the Meditrocity.) She usually came in during the mornings and afternoons, and as I was an evening regular, our times rarely overlapped.

Our very few interactions over the years had been commercial in nature. She walked from table to table selling her books of poetry, and I, peeved, declined every time. It was hypocritical of me — do my words count for more for being mine? — but I went to the Med to escape being constantly advertised to. (Also, I admittedly lack the patience for poetry.)

Only now do I think to look up her work. I don’t do well with poetry and didn’t want to get too many for free, but in what little I read, she got it right.

“Half the people here can’t do anything but magic,” she wrote in her poem “Anniversary Party at People’s Park.”

That’s true of all the great places. And all the best people.