By Lynn Rapoport

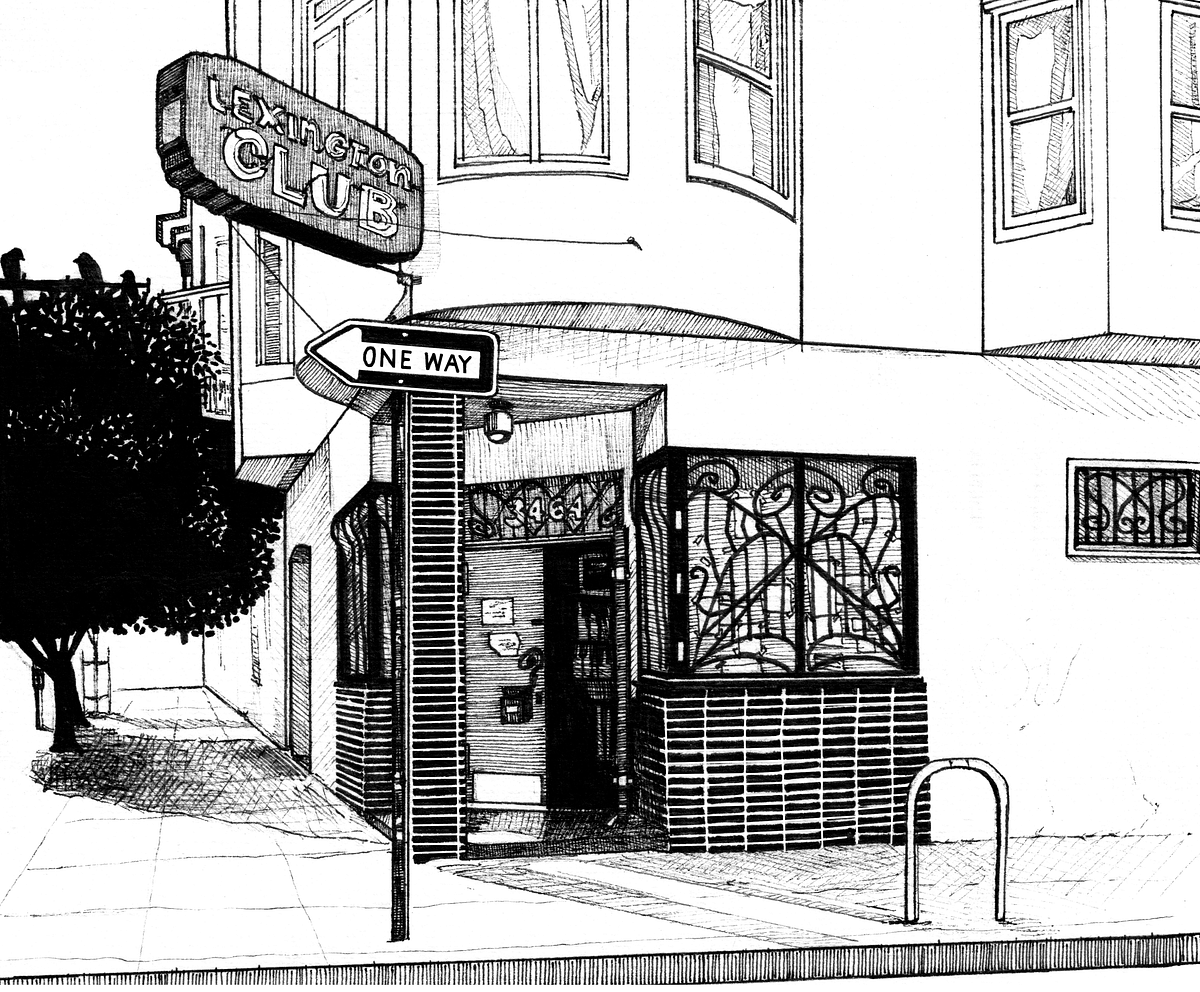

At 9 o’clock last night, the day the news broke that Lila Thirkield was selling the Lexington Club — 18 years old and an institution; for a long time, or still, depending on who you talk to, the city’s only full-time dyke bar — the interior of the place looked pretty much the way it always looks in my head. It was the latest configuration of a scene that had lured me in there so many times during the bar’s tenure at the corner of 19th Street and Lexington: a dark little Mission dive with glowing red walls, a pool table, a pinball machine, and a couple of hot bartenders, filled wall to wall with queers.

Near the back of the room, my friends and I took grainy pictures in the light of the Dracula pinball machine. Someone turned the jukebox down. One of the bartenders screamed to the packed house, “We fucking love you!” and the whole place raucously fell to pieces in response.

Years ago, before coming out, before my first date with a girl, before the day it dawned on me that I’d gradually become surrounded by queer community, I used to walk by the Lexington — a convenient block and a half from my house, though I would have gone way out of my way to get there — with my dog, too shy to even look up at the tough, hot queers hanging out on the corner smoking, just sort of vaguely hoping that one of them would drag me inside. A year later, having somehow made it there on my own, I leaned against the bar and watched the worst crush of my life drip candle wax on a hot femme draped over a table. I can still remember the immobilizing surge of awe and fright and attraction I felt, and it seemed intertwined with the place where it was happening.

A few years more, and the Lex was basically my local bar, the place where we went after Ladyfest planning meetings and for sweaty dance parties and to stage breakups and get over them; where my friend Railroad shot a film about a gang of revolutionary, roller-skating bank robbers; where the place exploded one night with rumors that Joan Jett had just passed through; where what felt like the entire sold-out house of the Victoria Theatre poured in after the 2001 Frameline screening of the S.I.R. Productions queer porn Sugar High Glitter City, including its simple-carb-loving, sticky-fingered cast; where if it weren’t for the line of dykes standing by outside the door, you could have spent a couple hours scanning the collage of graffiti on the bathroom stall walls, looking for secret messages.

Many more years later, it seems funny how much pressure I put on this one little street-corner bar to irrevocably reorient my life, though countless smaller dramas did unfold there that contributed incrementally. But it was always clear from both the swelling crowds and the snarking commentary (too sceney, not friendly enough) that the Lexington drew that I wasn’t the only one projecting all sorts of hopes and anxieties and expectations onto the place. And judging by the heartbroken outpouring online over the last 24 hours, and the heartfelt gratitude flowing toward Thirkield on the Lexington Facebook page for giving us this place for so long, the Lex somehow managed to come through, for many of us, on all that outsized promise we saw in it.

In an interview with Marke B. for 48 Hills and in a message to the community that she posted on Facebook, Thirkield talks about a drastic rent hike in the face of the changing demographics of the city and the neighborhood, the diminishing numbers of patrons making their way to the Lex. Shacked up, domesticated, still fond of the whiskey drinking, but less given to drifting toward the bar of an evening, I’d been rashly assuming that another generational wave of dykes and queers had taken over. It certainly looked that way some nights when I passed by that corner, some 15 years later, walking another dog, less magnetized by the place, though still willing to be dragged in by a friend for a cocktail or two.

Yesterday I had to wonder, having written an elegy for the fallen San Francisco Bay Guardian a mere eight days previous: Are the rest of my days here going to be a series of dispiriting news briefs on beloved institutions that failed? Except that you could never say that the Lex failed, having played a huge part in the lives of drinking, romancing, queer-culture-making S.F. for the last 18 years.

When I got home from work, I dug up my battered copy of a 1990s history of 20th-century lesbian life, flipping through it for old photos and mentions of other dyke bars over the decades. Mona’s 440 Club, Maud’s, Kelly’s Alamo Club, Amelia’s — places I’d never been to, and would never see, except for the Amelia’s sign that gets raised every year for Pride at that bar’s successor, the Elbo Room (itself the object of persistent grim rumors about its life span). I’m trying to take some sort of cold comfort in running through those names: that this is the sort of thing that has happened before and won’t ever stop.

I believe what Thirkield says, that if she thought the Lex could be saved, we wouldn’t be hearing from her, and last night would have simply been another night at the bar. You’d have to be willfully oblivious not to see how things have changed, how much harder it’s gotten for many community spaces, queer and otherwise, to stay rooted in the local landscape. But she also talks about planning new ways to carve out space, and I’d like to think it’s true that the queers won’t be stopped. Maybe a new spot will open on the corner of 19th and Lexington, and we’ll flood in there one night, Guerrilla Queer Bar style — though undoubtedly the drinks will cost twice as much as the Lex ever charged. But I still hope that, someday soon, someone will add another sanctuary to that list of dyke bar names, and that dykes and queers will flood the new space instead, communicating in numbers that this place, this neighborhood, this city is still ours.