We’ve all had the experience of going out to eat out with that guy. The friend who berates the taco-truck driver for not carrying a gluten-free Paleo option. The cousin who won’t touch a thing till he sees every letter of recommendation that came with the asparagus. And let’s not even get started on the chicken.

But these sorts of demands by diners are often met with less hassle than when one makes a simple request to see a restaurant’s most recent health-inspection report.

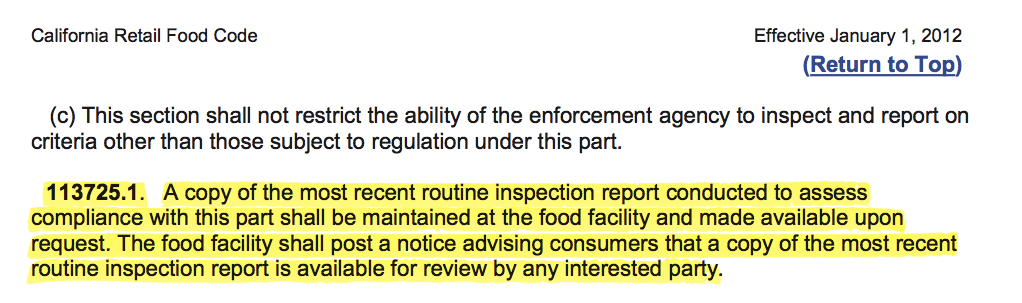

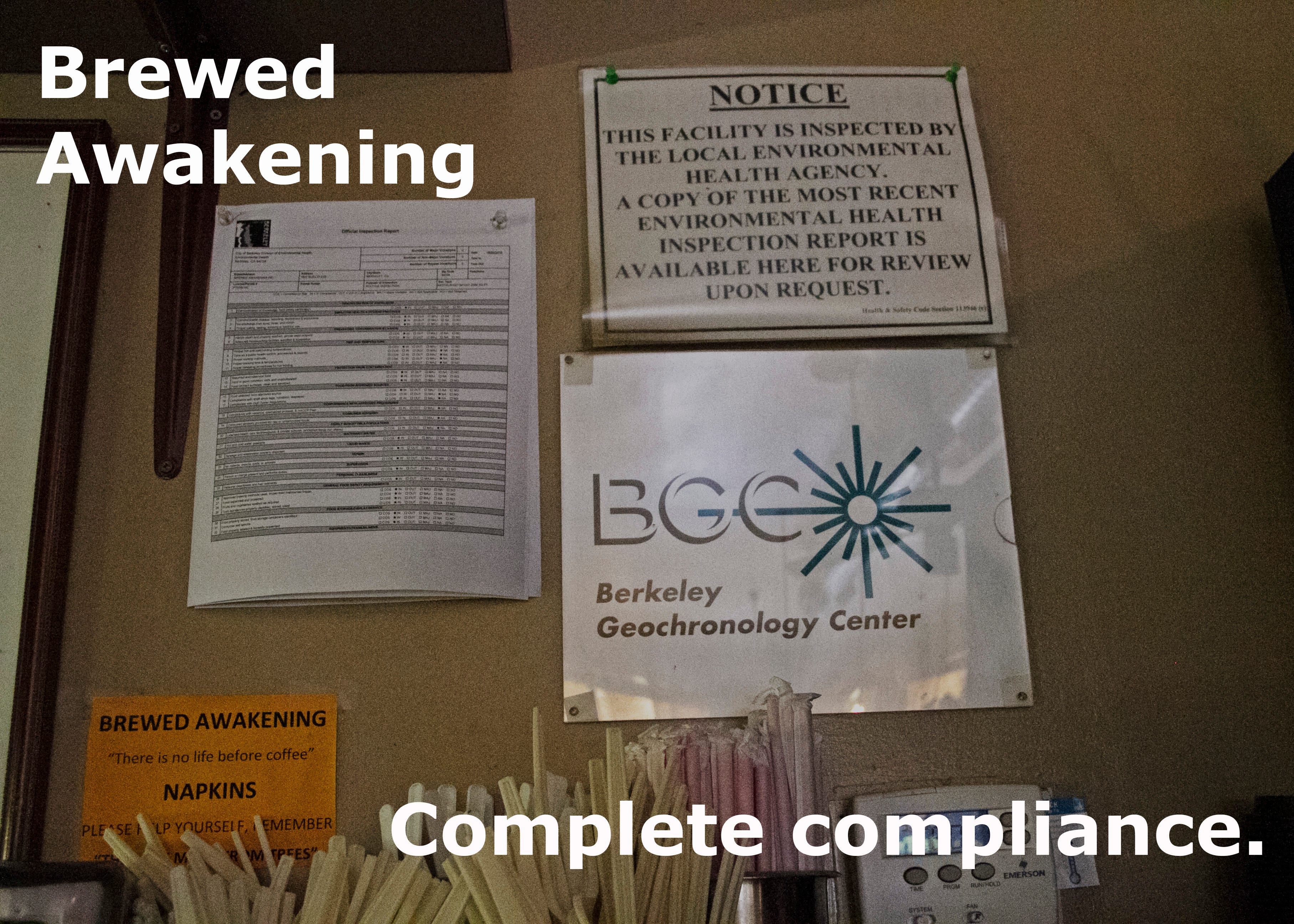

Restaurants are required by state law to post a notification that a copy of the most recent health-inspection report is available upon request. And if anyone asks, they are required to present it.

Chefs and restaurant owners understand that it’s good for business to be inclusive and diverse in their menu options. But the thing is, they are not legally required to provide diners with alternatives to suit diners’ spiritual, medical or mythical dietary restrictions. They are, however, required by state law to post a notification that a copy of the most recent health-inspection report is available upon request. And if anyone asks, they are required to present it.

So we thought we’d test that out. Since both of us live in Berkeley, we started there. Why not? Put together, we probably constituted “any interested party.”

Berkeley

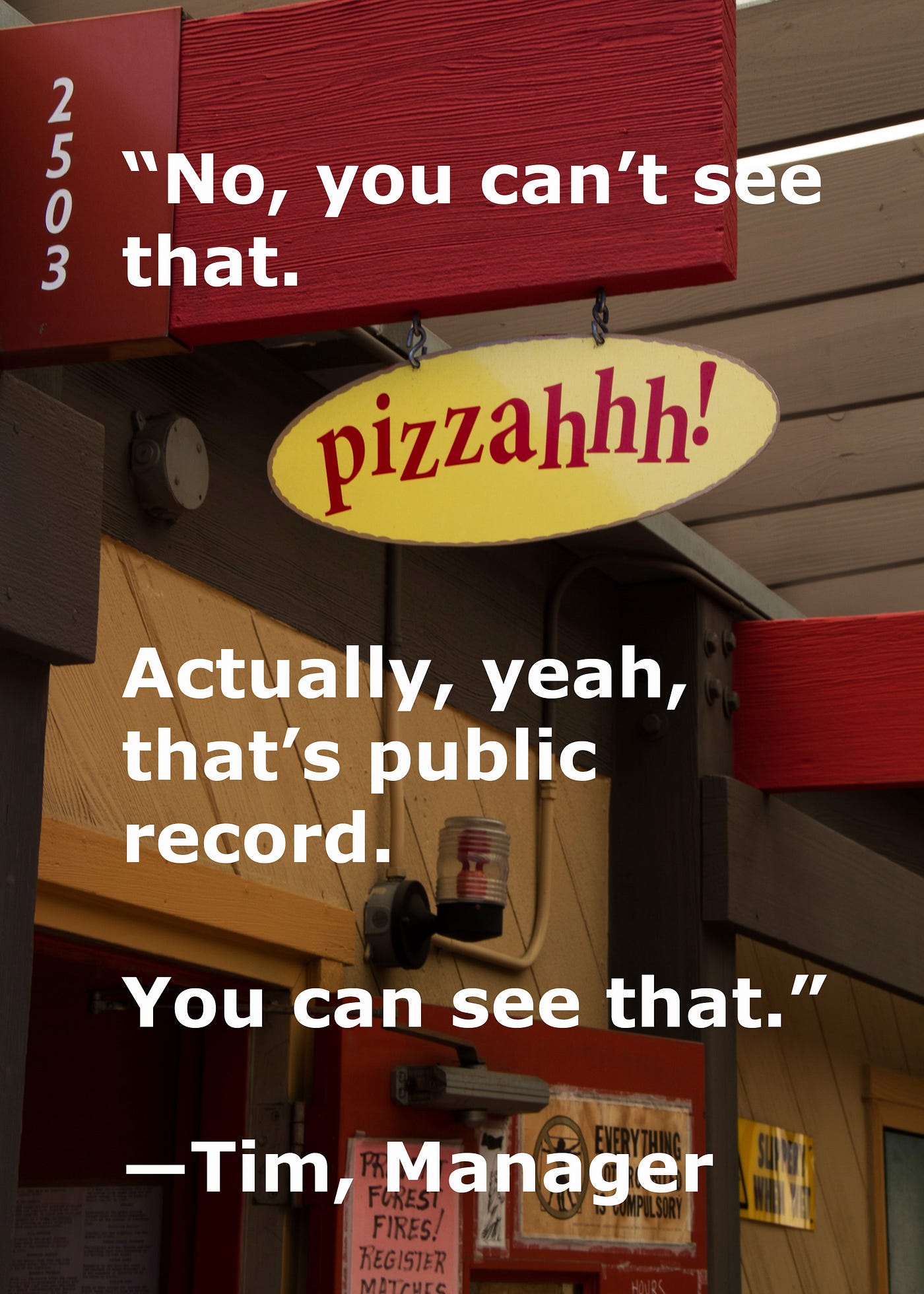

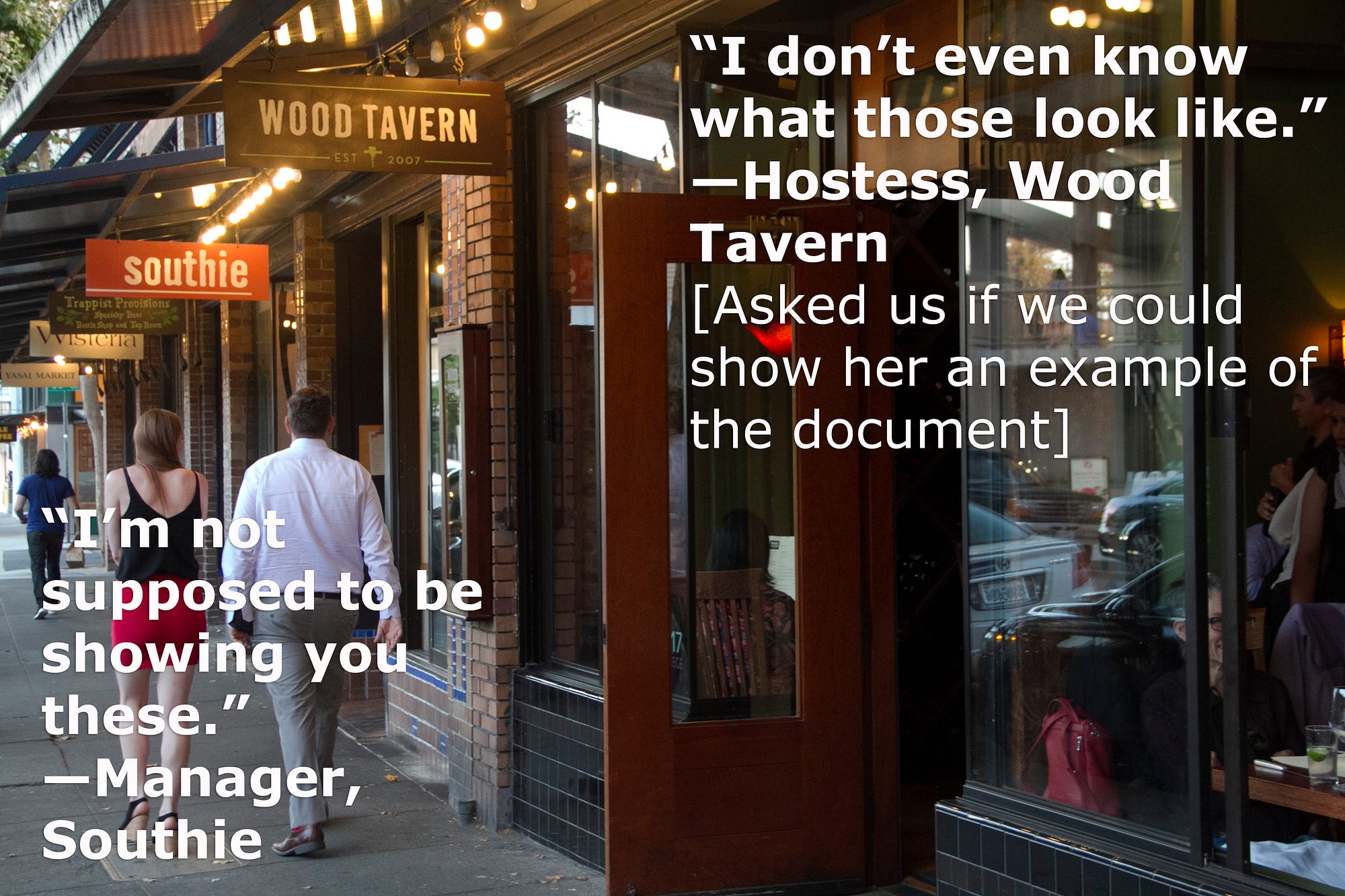

So our record in Berkeley was two for three, which wasn’t bad but hardly statistically conclusive. However, Berkeley is unusual, being one of only four cities in California that does not rely on the local county for health inspections. But given that the report-posting rule is a state law, we went to Southie and Wood Tavern on College Avenue in Oakland and asked to see copies of their most recent health reports. The results were less than stellar.

Oakland

Fernando, the manager at Southie, did eventually find the right document, but only after 20 minutes and after gathering the inspection reports for every year from 2003 to 2015. Only after showing him our copy of the California state law did he agree that we might, maybe, kinda have a right to see the information. And he pointed out the card in the window, which is a fair indication of a restaurant’s reliability but is not the report itself.

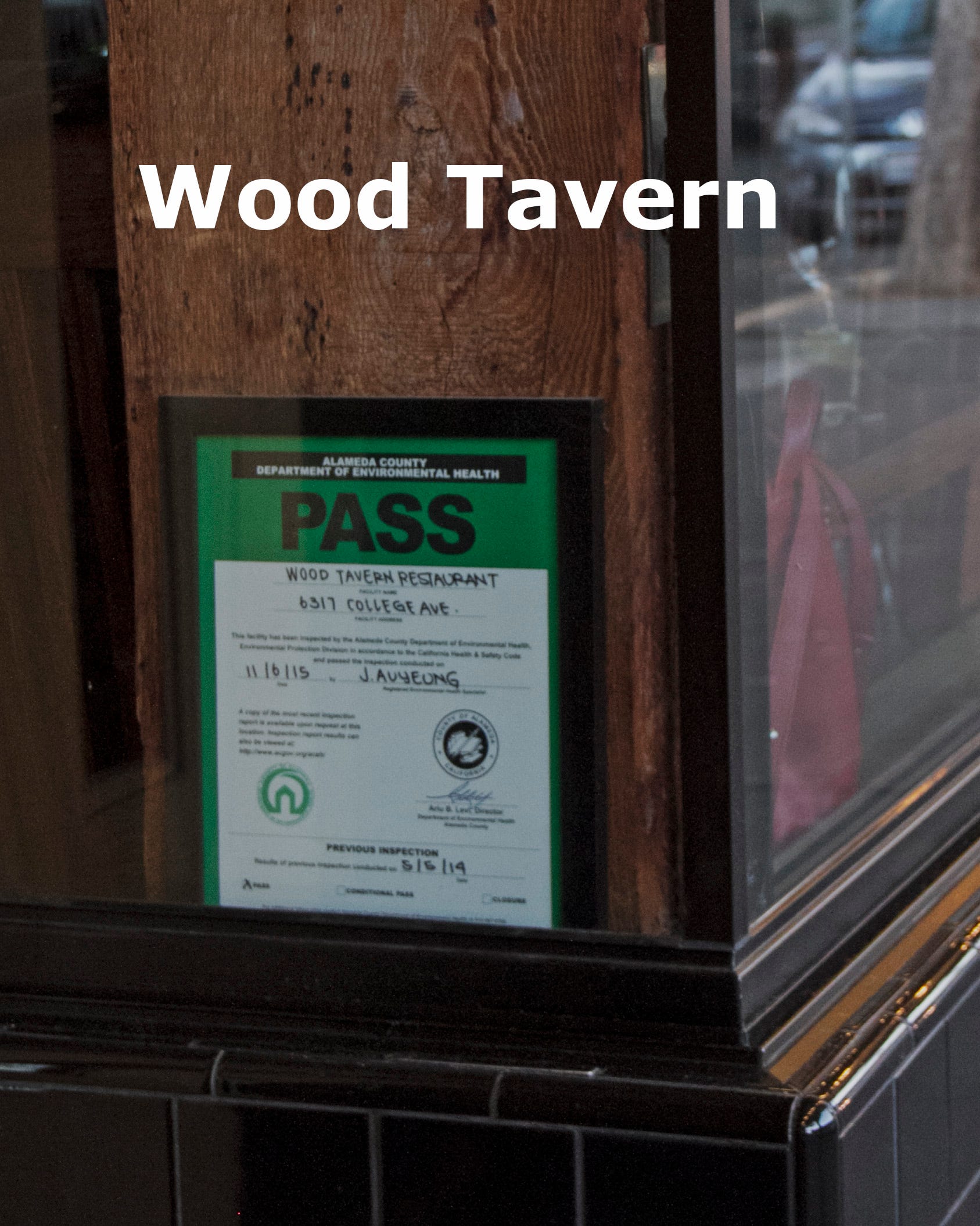

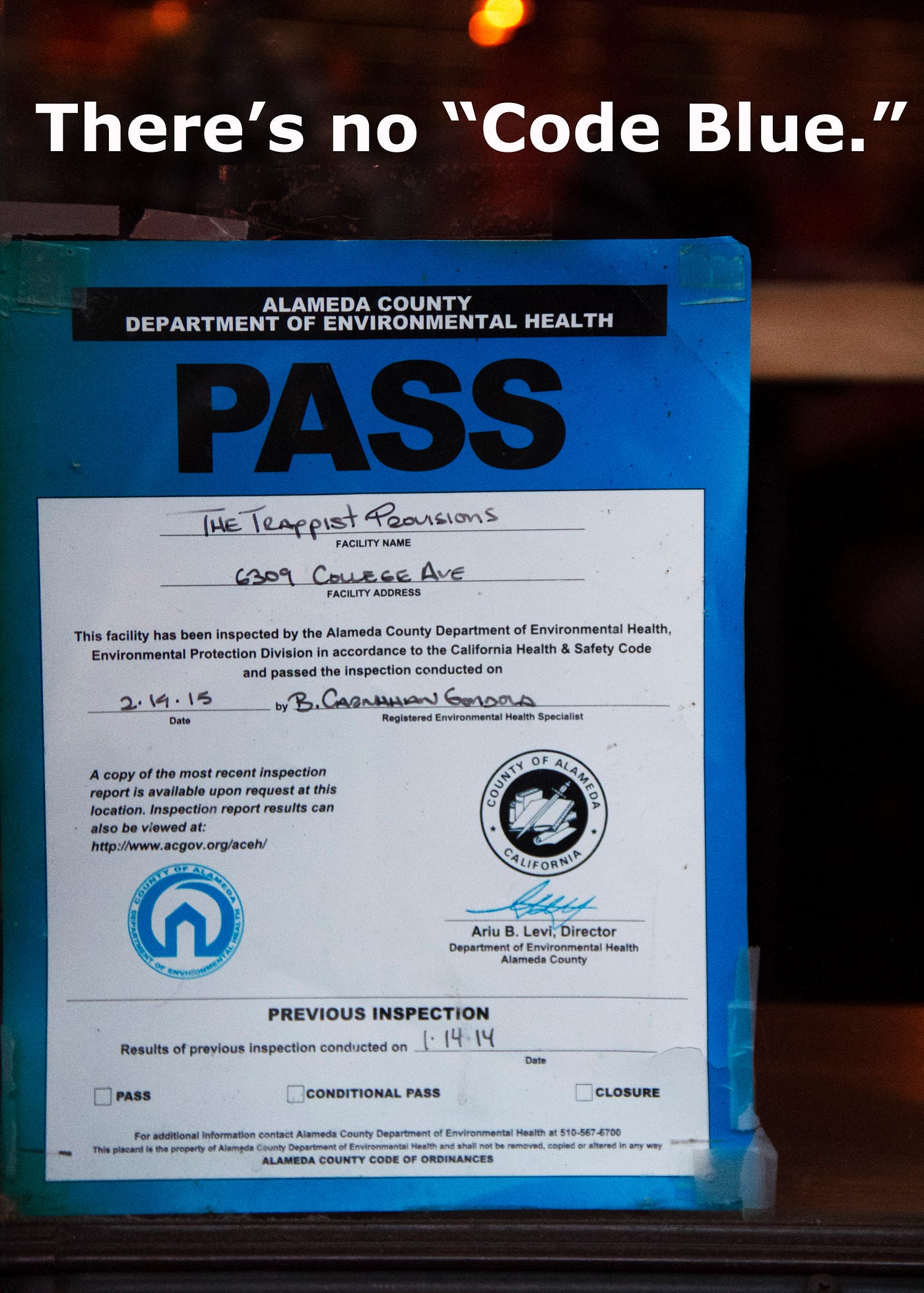

Alameda County uses a color grading system. (And as of this past April, so does Contra Costa County.) They use a traffic-light metric of green, yellow and red to show a restaurant’s general level of sanitation. The colors mean exactly what you think they do. With the exception of Berkeley, all dining facilities within the county are required to post the grade their business received at its most recent inspection.

Both Southie and Wood Tavern had their cards in the window.

But so did their neighbor next door, the Trappist, which had a green placard posted from February of 2015 that had since faded to blue. Two possibilities:

- Trappist forgot to post their most recent inspection card.

- They haven’t been inspected in a year and a half.

San Francisco County does not use the color system, but it’s still part of the state, so just for kicks, we went back — one year since this article’s publication — to the worst Yelp-reviewed restaurants in San Francisco.

San Francisco

Chinatown Restaurant

Our efforts to get a copy of the health report went like an Abbott and Costello routine.

Waitress: Ready?

Cirrus: Yes, tea please.

W: And what else?

C: Just tea.

W: Nothing to eat?

C: Just tea, thank you.

W: You don’t want anything else?

C: No, just … actually, yes. Can I please see a copy of the most recent health-inspection report?

W: The … the what?

C: The health-inspection report. May I see a copy of the report from the last time this place was inspected?

At this point the waitress became suspicious.

W: “Where are you from?” she asked.

I decided to be truthful.

C: “I live in Berkeley,” I said.

W: “What’s your job?” she said. “Why are you asking? You’d have to talk to the owner. We don’t give that information out. It’s in the office.”

C: “Where is the office?” I asked.

The waitress gestured toward a window. Across the street? Across the block? San Mateo?

W: “You’d have to talk to the owner,” she repeated, and then the same words again, but faster. “Tomorrow. The office closes at five.” She paused for a moment and added, “We’re just waitresses. We don’t have that.”

The interrogation had come to resemble one of those bad Westerns where the meddling do-gooder torments the innocent tavern keeper with questions. I decided I’d tortured the waitress enough and left without the report.

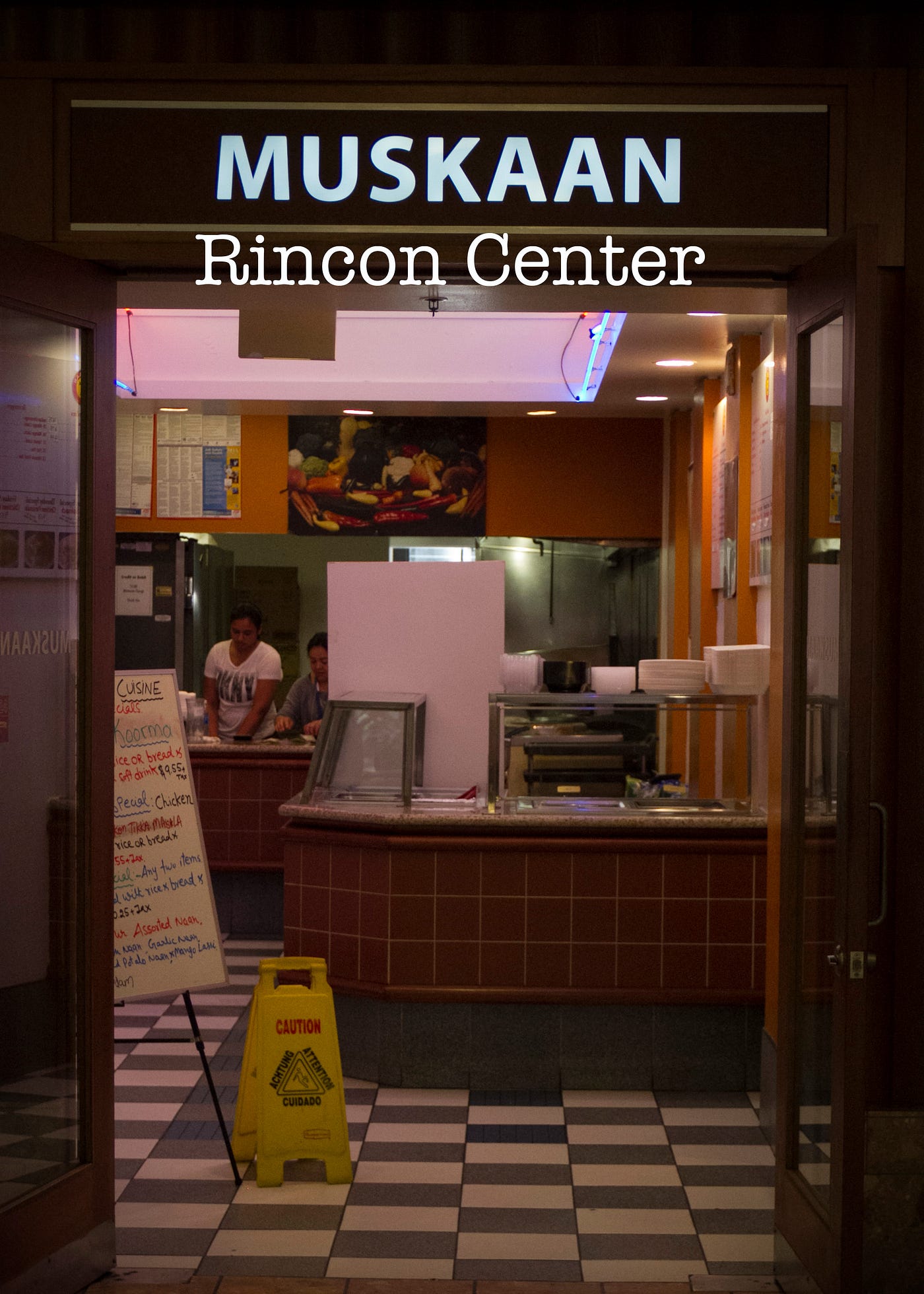

Muskaan

The reviews for Muskaan weren’t much better than those for Chinatown Restaurant. Actually, they were quite a bit worse. And the response from the staff was equally confused.

Staff: “The … ‘elth’ report?”

Cirrus: “Health report.”

S: “You mean the score card?” she asked, and pointed at a posting on the wall. The poster showed a score of 100.

No, we explained. We were looking for the actual inspection report, not just the score. We wanted to see what the inspector had seen, what they had written down, what food temperatures and safety precautions they had recorded and what vermin, if any, they had seen.

S: “The manager isn’t here right now, and I don’t know where that is,” the hostess said.

C: “And when — ”

S: “She’s out of the country.”

C: “Ah.”

S: “Excuse me, sir, but do you work here?”

Sinbad’s

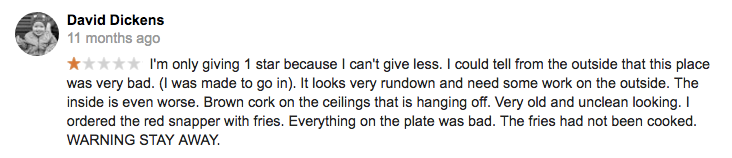

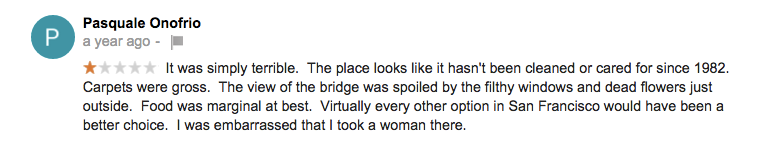

Google Maps guided us to the now-vacant Pier 2, where Sinbad’s was a year ago. The app lags behind the times, listing the menu, hours and celebratory photos of what’s now just a place of “used to be.” The restaurant hadn’t so much closed as been disappeared, like ash shaken off the stub of a cigarette. Nothing but a few cracked tiles and one broken table on a slab of empty concrete. But with a little Internet archaeology, you can still find reviews for the joint.

Looking at the pier, I could understand both David’s and Pasqual’s points. The spot was definitely run down, and the flowers were certainly dead. But at least the building wasn’t there to block the view of the bridge anymore.

Shiki

Well, so much for Shiki. Maybe the spoiled salmon rolls were finally too much for business. There might be more to say, but it’s hard to get nostalgic for a mall-type sushi place.

The Takeaway

Out of the seven operable restaurants we visited, we got to see three reports. And of those three, only two restaurants knew exactly what we were talking about — which, for this highly informal study, means a 72% response rate of “Huh?”

Maybe the restaurants that failed this simple test had feigned ignorance and hidden poor inspection reports, or maybe they just aren’t aware of the state law.

“The reason this law exists is for greater public transparency,” said Nancy Sarieh, a public information officer with the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “So customers can make informed decisions and see previous violations and what steps have been taken to correct them.”

San Francisco has around 30 inspectors reporting on around 7,400 sites throughout the city, the largest jurisdiction of the three we studied. The department supervises restaurants, grocery stores, liquor stores, food trucks, gas stations, hospitals, schools and anyplace else where food is prepared and sold.

Our experience at Wood Tavern and other venues in Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco made us wonder just how much instruction city and county health departments are providing.

Sarieh was surprised at the general reception of bafflement we received when we had asked for the report. “Every place should have one in order to operate,” she said.

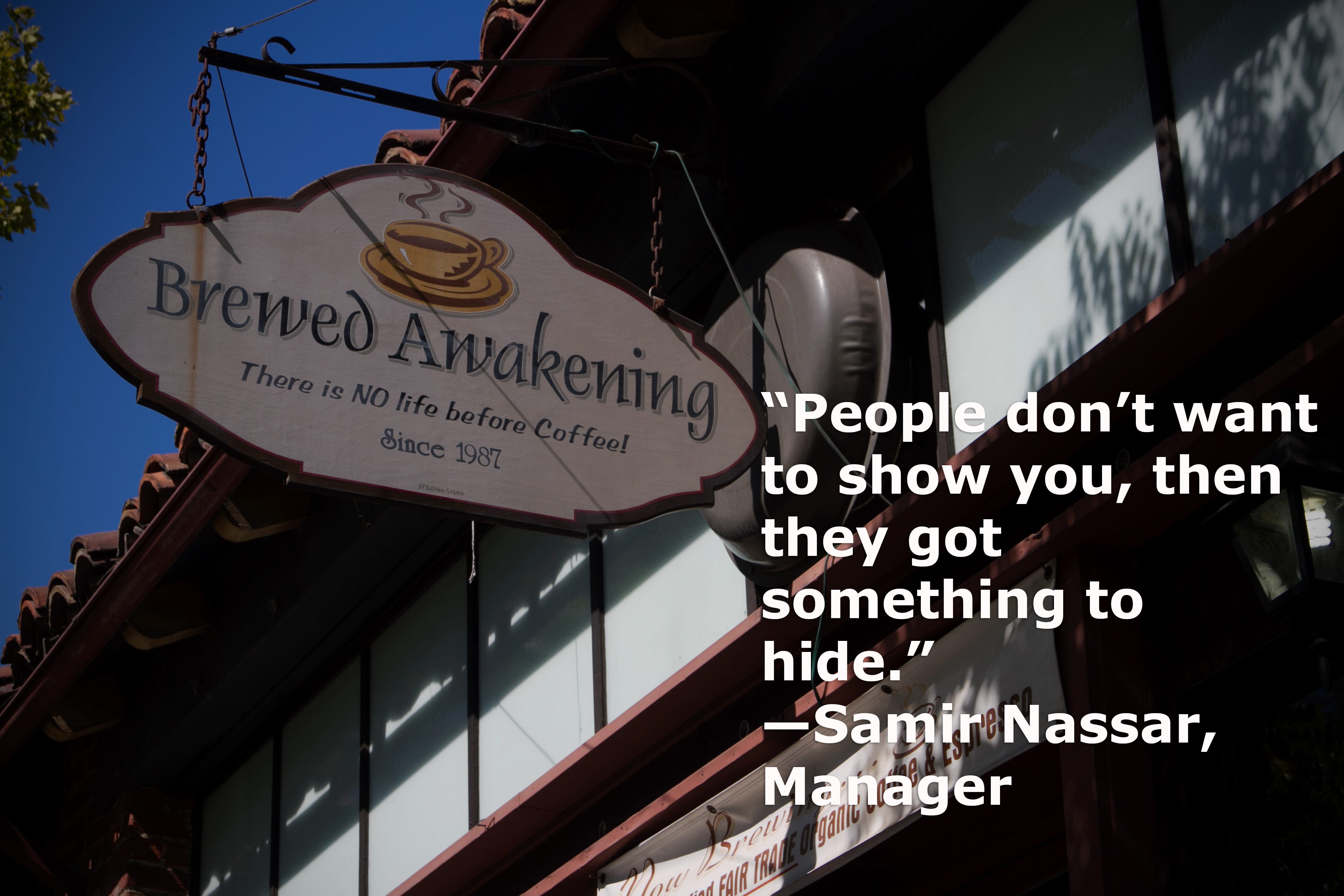

Most of the restaurants we visited had nothing to hide, with few to no violations at all. We asked Manuel Ramirez, environmental health manager for the City of Berkeley’s Environmental Health Division, about our concern that the majority of restaurants in Berkeley do not display the required sign stating that “health-inspection reports are public and will be made available to any party upon request.”

“It’s just like anything else,” Ramirez said. “Unless you remind people to do it, they’re probably going to forget.”

Ramirez’s response seems like an admission of failure. If restaurants are forgetting, then the department is probably not reminding.

On the basis of our encounters with restaurant staff, they need a little more than just reminding. Our experience at Wood Tavern and other venues in Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco made us wonder just how much instruction city and county health departments are providing.

“What does it look like?” the hostess at Wood Tavern asked us when we inquired about the most recent health-inspection report. We showed her a picture of the document, and still she could not find it.

Whatever the reason is that a restaurant doesn’t provide copies of their health-inspection report, one thing is for sure: access to the document is a right, not a privilege. If the waiters use those little metal spatulas to clean bread crumbs off your table, or they scoop horchata out of a vat, the law is the same.

You don’t need to be reporters, students or even patrons to obtain access to these records. But as we found in our own reporting, we needed a print-out of the law, IDs, tolerance from angry restaurant workers and a hell of a lot of perseverance.

And it probably wouldn’t hurt if for a while we just went some other place for lunch. Some place where the staff won’t know either of us as that guy.