Being a professional wrestler is brutal. Ligaments get torn. Necks get broken. Heads get concussed. And the wrestlers of Hoodslam, Oakland’s underground wrestling tournament, are fearless champions of the sweat-soaked sport.

But unlike more traditional wrestling matches, Hoodslam, which takes place every month at the Oakland Metro Opera House, is “performance art” with few sanctions: Fighting literally transcends the ring, often taking place either directly in the middle of the audience or on top of the bar; smoking and drinking is encouraged; and if you’re lucky, the host will pour a lukewarm shot of whiskey directly into your mouth.

Sign-up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best content about life in the Bay Area in your inbox every week. What could go wrong?

When I attended on a Friday earlier this year (pre–shelter in place), people packed the house. As the program ramped up, hundreds of goths, geeks, and metalheads ironically chanted, “Fuck. The. Fans!” with fervid glee, pounding their fists on the wrestling mat and smoking fat spliffs. I had to be vigilant since, according to the host, at any point during a match, a wrestler could fly out of the ring and into the crowd.

The only thing between you and them, he says, is “weed smoke and your shitty life decisions.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. While shooting photos in the front row, I got covered in wrestlers’ sweat, spittle, fruity cereal, whiskey, and flour. My sobriety, too, immediately went out the window. During the opening match, one of the wrestlers handed me his soggy joint, advising me to pass it around. So I did — and stoned I got. I considered it all a part of the experience.

With its liberating atmosphere, it’s easy to see why Hoodslam gets such a consistent turnout. “It’s like an oasis,” says in-house photographer Mark Johnston. Ultimately, though, I was drawn to Hoodslam because of its people. I wondered: Are any aspects of the wrestlers’ characters real? Who are the people behind the personas? And why do they do it?

After interviewing Hoodslam’s motley crew, I learned that many of their personas are amalgamations based on themselves and their past experiences. They also have diverse histories: Some wrestlers are former civil servants, others are combat veterans in recovery, and some, well, are stoners who simply like to entertain.

The Stoner Brothers

“Can you summarize the Stoner Brothers in three words?” I asked twins Dustin and Derek Mehl backstage about their personas.

“High as fuck,” they say, puffing on spliffs as they lace up their boots.

The Mehl brothers are professional wrestling trainers by day and say that their in-ring characters are simply them “turned up.” They also wrestle for straightforward reasons. “To get high and throw people,” they say. “We just want to entertain.”

Handsome Devil Anthony Rivera

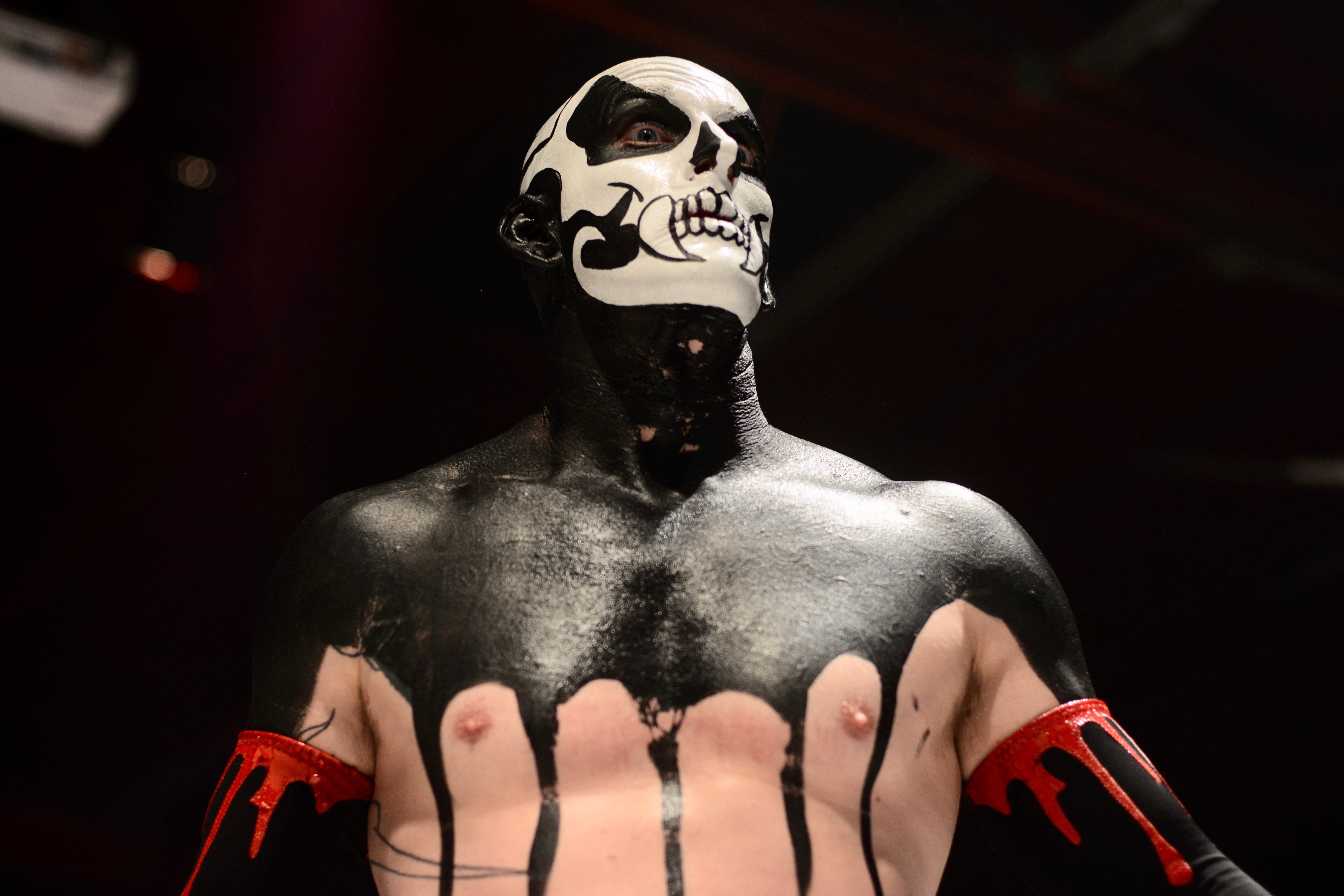

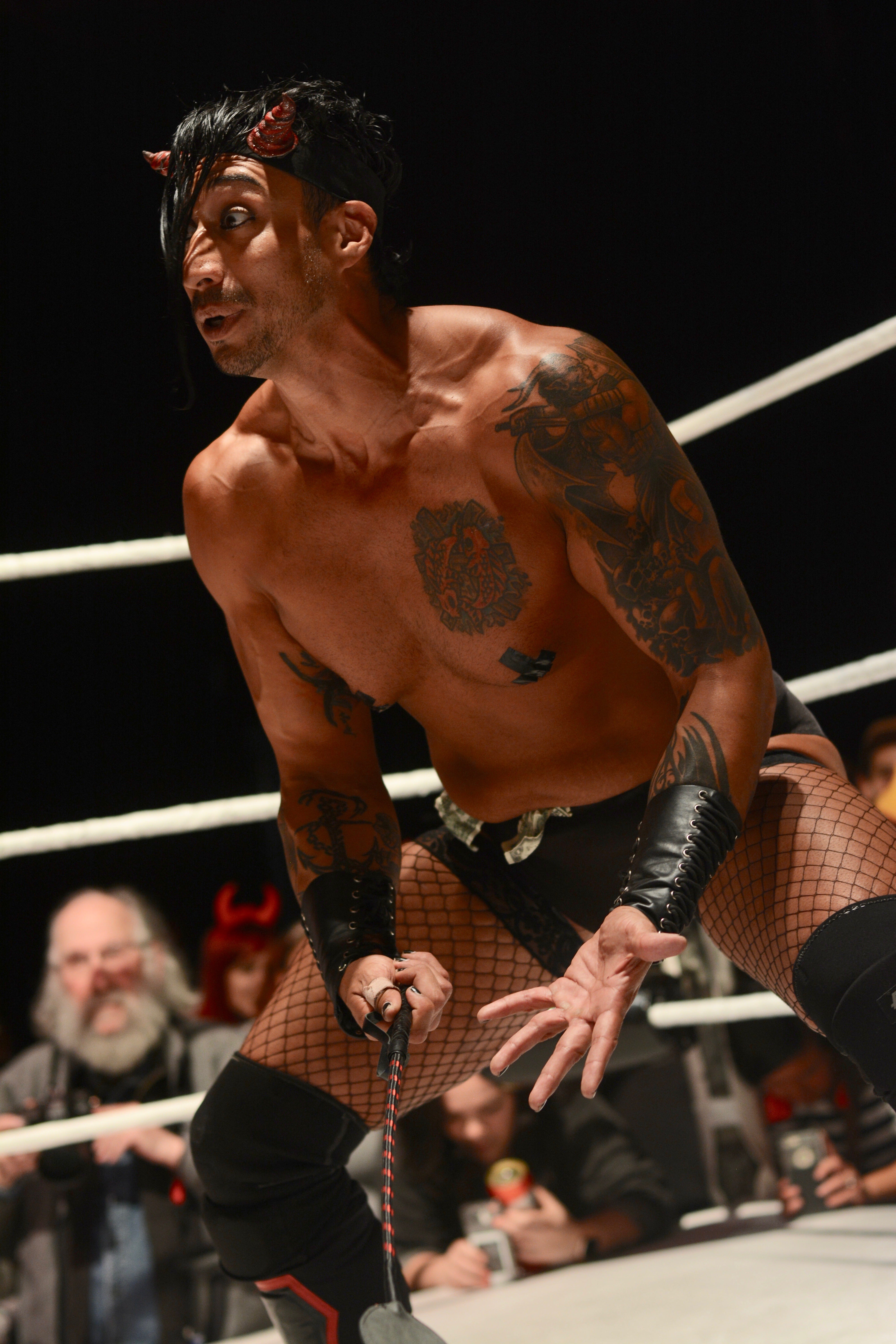

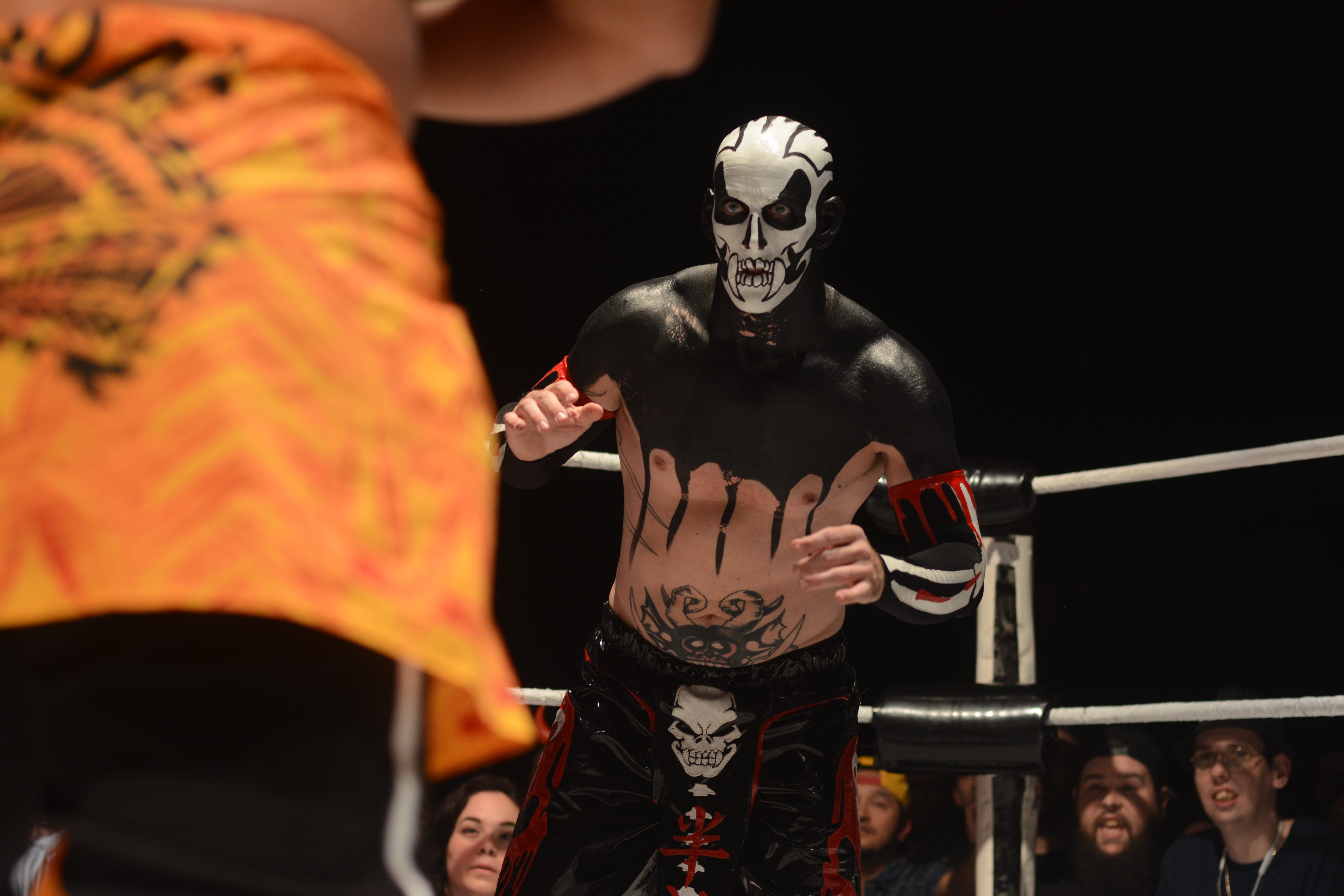

Some wrestle for more complex reasons. Anthony Rivera, whose character is Handsome Devil Anthony Rivera, actually has a gentle, boyish demeanor despite his demonic persona, which is oozing with sexuality. While we talked, I helped him lace up his leather arm cuffs, and it felt no different than zipping up the back of a friend’s dress.

In the ring, his character, according to Rivera, is a “big genderfuck” and inspired by equality. “Handsome Devil is an equal opportunity lover and equal opportunity fighter,” he says. Rivera is a combat veteran and a stripper who is using his GI bill to get a degree in business marketing from Phoenix University. He steps into the ring because he wants to show that he’s in recovery — and that recovery is possible for others.

Dark Sheik

Another reason Hoodslam is special is that it creates a safe space for its wrestlers, many of whom have variant gender, sexual, and ethnic identities. Dark Sheik, aka Hoodslam founder Sam Khandaghabadi, told me that the event promotes inclusivity — and that strict rules are placed in order to honor wrestlers: no racism, no homophobia, and no misogynistic slurs against women.

“From day one we’ve had a rule that all are welcome,” she said. “I grew up as an Iranian kid who didn’t always feel safe in the audience at wrestling shows. I never want anyone who attends our events to feel like I did back then. This little memory has somehow guided us to the frontlines of progressive movement in independent wrestling.

Everyone looks out for everyone, “Our core group is more tight knit than most families because we’ve grown and built and struggled and survived together,” she said.

As to why she steps into the ring, she finds the demanding type of performance rewarding.

“Many are familiar with what they see on TV, and even that has grown leaps and bounds as far as being a more respected art form,” she said. “But it’s never been done justice on a major scale. Nowhere else can I perform a story with a one-take fight scene and improvised dialogue done in the round — and the audience provides call and response along with throwing me cash tips while handing me liquor and weed. You don’t see that on Broadway.”

Broseph Joe Brody

However, every storyline needs an antagonist, and in wrestling, this is no exception.

Hoodslam host A.J. Kirsch’s persona is Broseph Joe Brody. He describes his character as a douche.

“I wanted to create a bad guy,” Kirsch says. “I went to school at Chico State, which is notorious for party and frat culture, and I was working as a bouncer in the Marina District. I took some shreds of [my] own personality — I’m a gym rat — and I unironically, shamelessly, love Nickelback. I put those things together and figured the concoction would create a character that Oakland would hate.”

Between matches, Brody hypes up the audience by pouring them shots of whiskey, occasionally taking one himself and spewing it back onto the crowd — everyone is fair game, even his own mom, who attended the match that night.

BART-Man

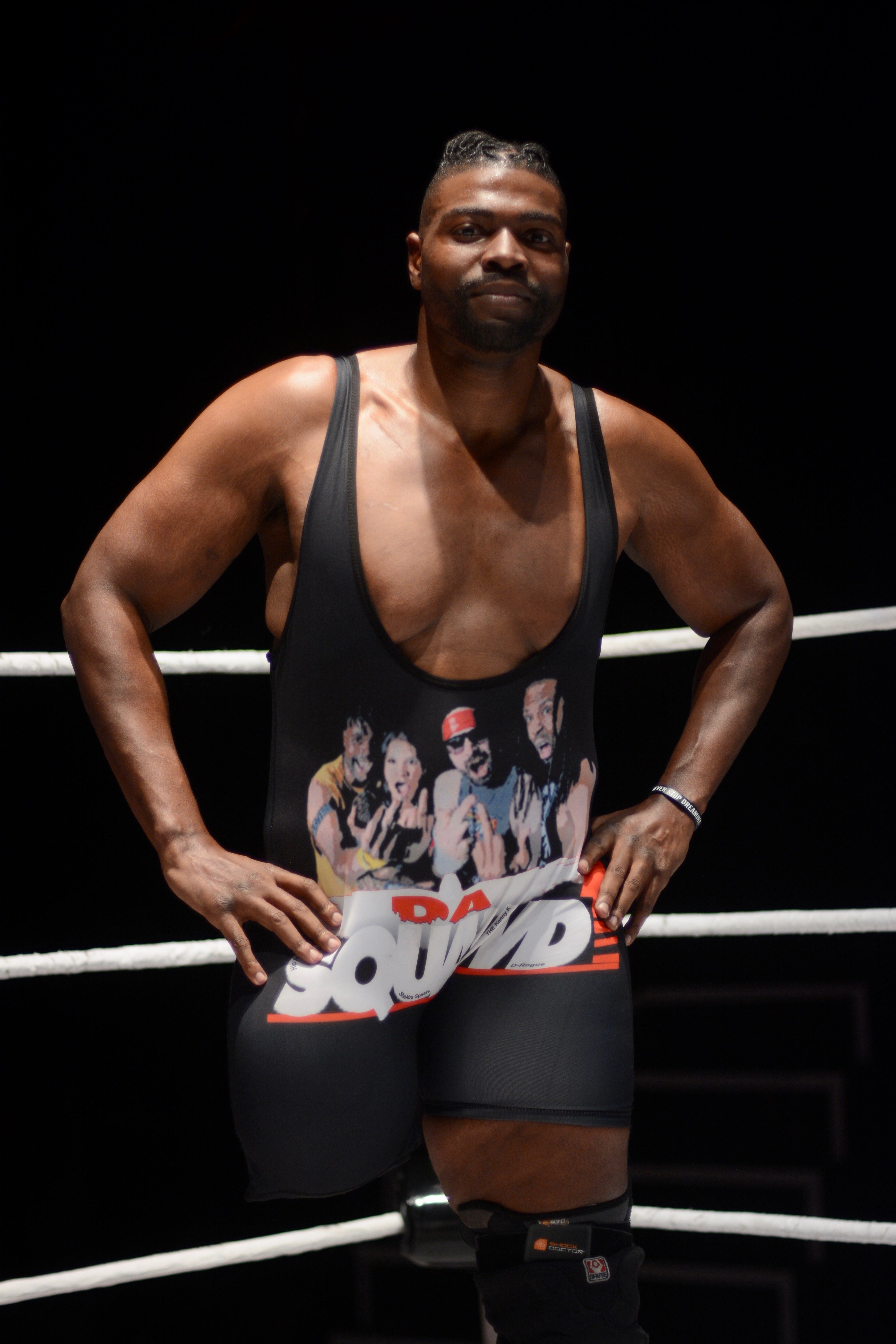

Other personas are based on reality. For instance, I spoke with BART-Man, who’s played by B.K. (he later insisted his real name was Bartleby, but I figured he had to be trolling me), who has worked as a BART station agent for four years. He describes his character as a “friendly transit luchador” and says that BART-Man’s most admirable trait is his capacity for positivity.

BART-Man steps into the ring to “build trust and love for public transit.” Admittedly, by the end of our interview, I had a fat crush on BART-Man. Was it his mysteriousness (what was behind that custom black-and-blue mask?) or his municipal charm? Either way, I was intrigued.

Ultimately, what I learned is that Hoodslam is not for everyone — it’s for an unusual type of someone. But that’s what makes it more than just entertainment. Its scrappy community is what makes it real, just like the tagline suggests.

To see the next tournament of Hoodslam, check out the event schedule here.