By Alyssa Oursler

The name “Silicon Valley” has become a stand-in for anything and everything tech. It’s synonymous with start-up culture, a symbol of disruption and innovation, and even the title of a hilarious TV show. But the high-tech phrase comes with an old-school origin story.

It all started as a catchy newspaper headline. Forty-five years ago, the nickname “Silicon Valley” first appeared in print as the title of an article about the semiconductor industry, which was then booming in Santa Clara Valley. Written by Don Hoefler, the article appeared in the weekly tech tabloid Electronic News. Rumor has it that Hoefler heard the phrase uttered casually over lunch and couldn’t pass up using it for his piece.

But as he noted in his article’s opening, the Silicon Valley story began long before.

Hoefler, who covered the industry and its major players for years, cites 1947 as the start of Silicon Valley. That’s when William Shockley, Walter Brattain and John Bardeen first demonstrated the transistor at Bell Labs in New Jersey. You can thank the transistor for modern-day Silicon Valley innovation; it’s the crucial active component in all modern electronics.

In the beginning, though, germanium — not silicon — was used as the transistor’s semiconductor. It wasn’t until 1954 that the nickname-worthy material was put into production by Texas Instruments.

So if the transistor was invented there, why isn’t New Jersey home to today’s tech scene? It’s tempting to toss out some Jersey jokes and stereotypes as the answer, but the question is legitimate, especially considering that leading banking, manufacturing and electronics companies were all located on the East Coast in the 1950s.

Shockley was a leader in the migration to the West. He was eager to commercialize the transistor and launched Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory in 1956 to that end. At the time, his ailing mother was living in Santa Clara Valley — then known as the “Valley of Heart’s Delight” for its flowering orchards — but that wasn’t the area’s only appeal. Despite its agricultural roots, technology was already brewing in the region thanks to Stanford University.

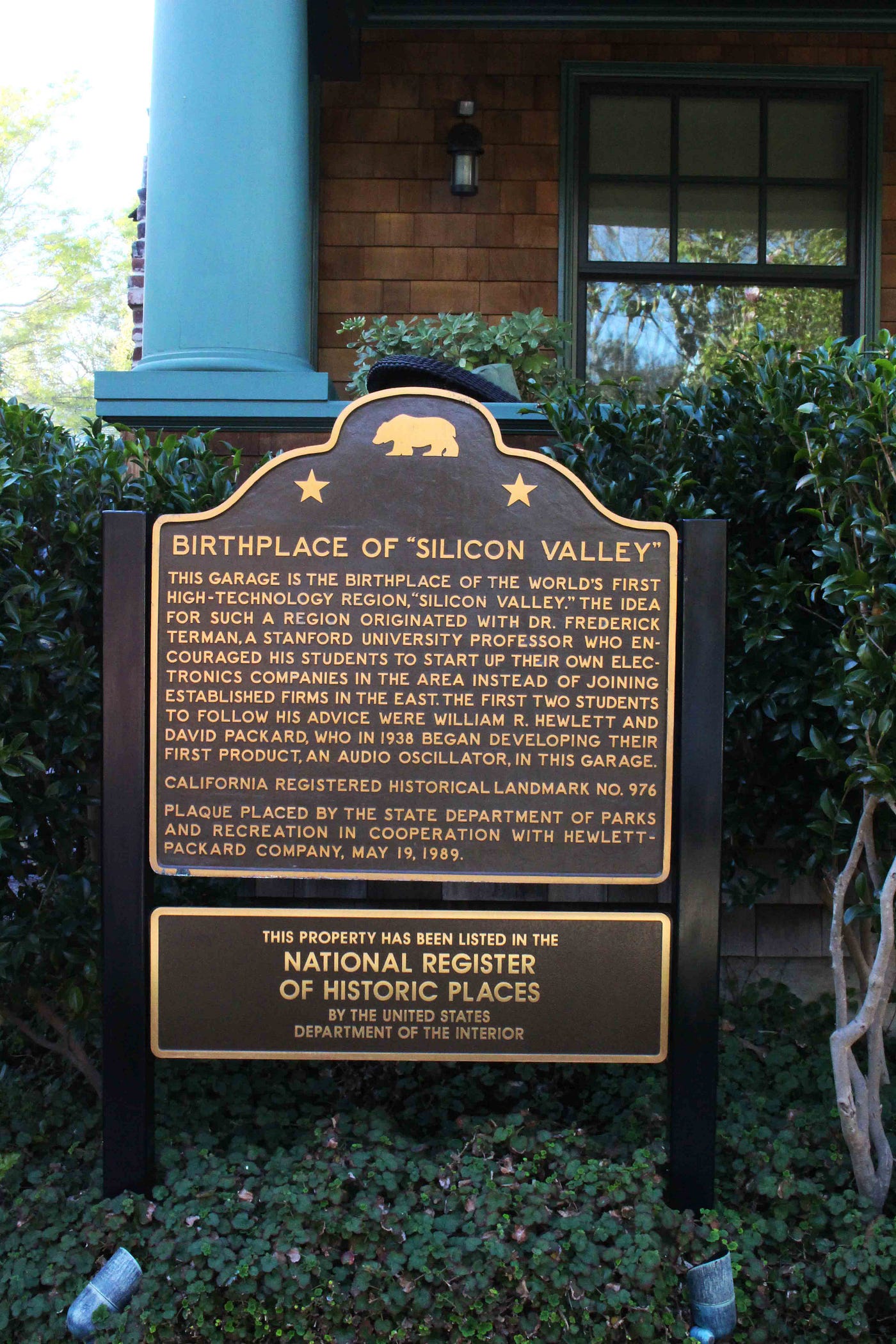

In an attempt to bridge academia and industry, Stanford began offering cheap long-term leases in the area. Professor Fred Terman, who joined Stanford in the 1920s, was also a champion of the high-tech industry and is often referred to as the “father of Silicon Valley.” Almost a decade before the transistor’s invention, he brought William Hewlett and David Packard together, supporting the venture they started in a Palo Alto garage. Stanford reports that Terman wrote Shockley a letter touting the benefits of opening up shop near the prestigious university.

Thus, Shockley Labs began in Mountain View and attracted superstar talent. One such superstar was Robert Noyce, the next lead character in this saga.

Of course, Silicon Valley encompasses more than just technology; culture remains at its core. That’s where Noyce comes in and why some historians prefer to say that Silicon Valley began a decade later than Hoefler dated its origin.

The year was 1957. And while Shockley had just won the Nobel Prize for the transistor, he was about to lose eight employees. The group, later nicknamed the “Traitorous Eight,” had funding from New York City, a charismatic leader in Robert Noyce and a vision. In an unprecedented move, they struck out on their own and launched a company called Fairchild Semiconductor.

Fairchild was led by Noyce and featured a culture partially inspired by his small-town upbringing. With a focus on empowering employees and rejecting East Coast hierarchy, Fairchild planted the seeds for the start-up culture that has snowballed into what Bay Area residents know today.

In just a few years, Fairchild helped birth the integrated circuit, which put disparate transistors into a single unit. Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments is credited with the concept, although his design resorted to germanium, which was not commercially viable. Silicon again saved the day—it was Noyce and company who printed the circuits on single silicon microchips.

Noyce later launched Intel, which created the first commercial microprocessor — essentially a programmable integrated circuit and the brain of all computing devices. He evangelized and lobbied for the device, on top of winning numerous awards. Meanwhile, countless Fairchild employees created their own spin-off tech companies. Noyce was also a mentor to Steve Jobs and others, initiating a Silicon Valley family tree of sorts.

As such, Noyce had been dubbed the “mayor of Silicon Valley” by the time he passed away in 1990.

By that point, it was clear Hoefler’s nickname had stuck, and by now we know that at the time of the nickname’s coinage, the region’s impact was just starting to be felt.