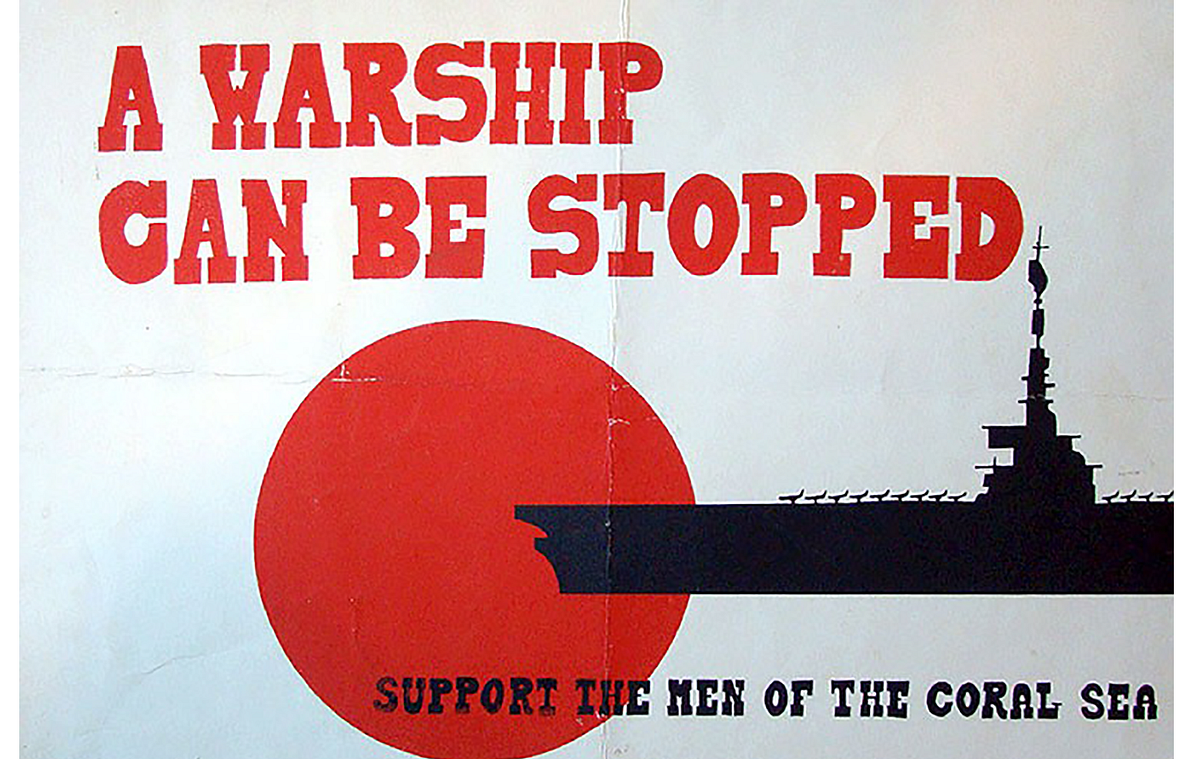

In early November 1971, the USS Coral Sea sat in the San Francisco Bay. The 45,000-ton aircraft carrier was slated to return to Vietnam that month, but at least 1,000 of the 4,500-man crew had formed an organization called Stop Our Ship and signed an antiwar petition. Their goal? To stop the ship’s journey back to the war-torn country.

In the days before the ship was set to depart through the Golden Gate, crewmen and civilians staged protests and vigils in San Francisco and outside the Naval Air Station in Alameda. In response, at the end of the Berkeley City Council’s regular meeting, members made history by signing Resolution #44,784, extending “sanctuary” for any crew members who opposed the war. Five days later, the USS Coral Sea headed west for Vietnam. Thirty-five men missed the departure, and at least one sought sanctuary.

Decades later, the conversation around sanctuary cities—now a national movement—is once again in the spotlight. The term isn’t specifically defined, nor does it have any official legal meaning, but it generally describes a city (or county) that limits cooperation with federal-immigration-enforcement agents and generally commits to protecting refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants who haven’t committed serious crimes.

“Sanctuary is a commitment, a moral commitment to our values of recognizing the inherent human dignity and worth of every person.”

The number of sanctuary jurisdictions in the US varies on the basis of the source, but it’s in the hundreds if you count all cities, counties and states. The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), a nonprofit that describes itself as nonpartisan but is also classified by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) as a hate group, puts the number at over 560. The Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC), a nonprofit advocate for immigrant rights, reported in 2018 that more than 400 counties have “stronger limitations on engaging in immigration enforcement” than the year before. In 2017, five states adopted statewide sanctuary policies, with California passing California sanctuary law SB 54, which the ILRC has described as “the most comprehensive state law limiting involvement in immigration enforcement throughout the state.”

The Trump administration has been vocal in its distaste of sanctuary cities. In March 2018, the Trump administration sued California and the state’s top leadership, saying California’s sanctuary statutes “reflect a deliberate effort by California to obstruct the United States’ enforcement of federal immigration law.” Organizations such as FAIR describe the growing movement as dangerous, especially as it relates to “criminal aliens” who have “recommitted crimes against innocent Americans.”

Just this past Friday, Trump tweeted that he is “giving strong considerations to placing Illegal Immigrants in Sanctuary Cities only” as a form of political retribution—payback, he said, for the fact that “Democrats are unwilling to change our very dangerous immigration laws.”

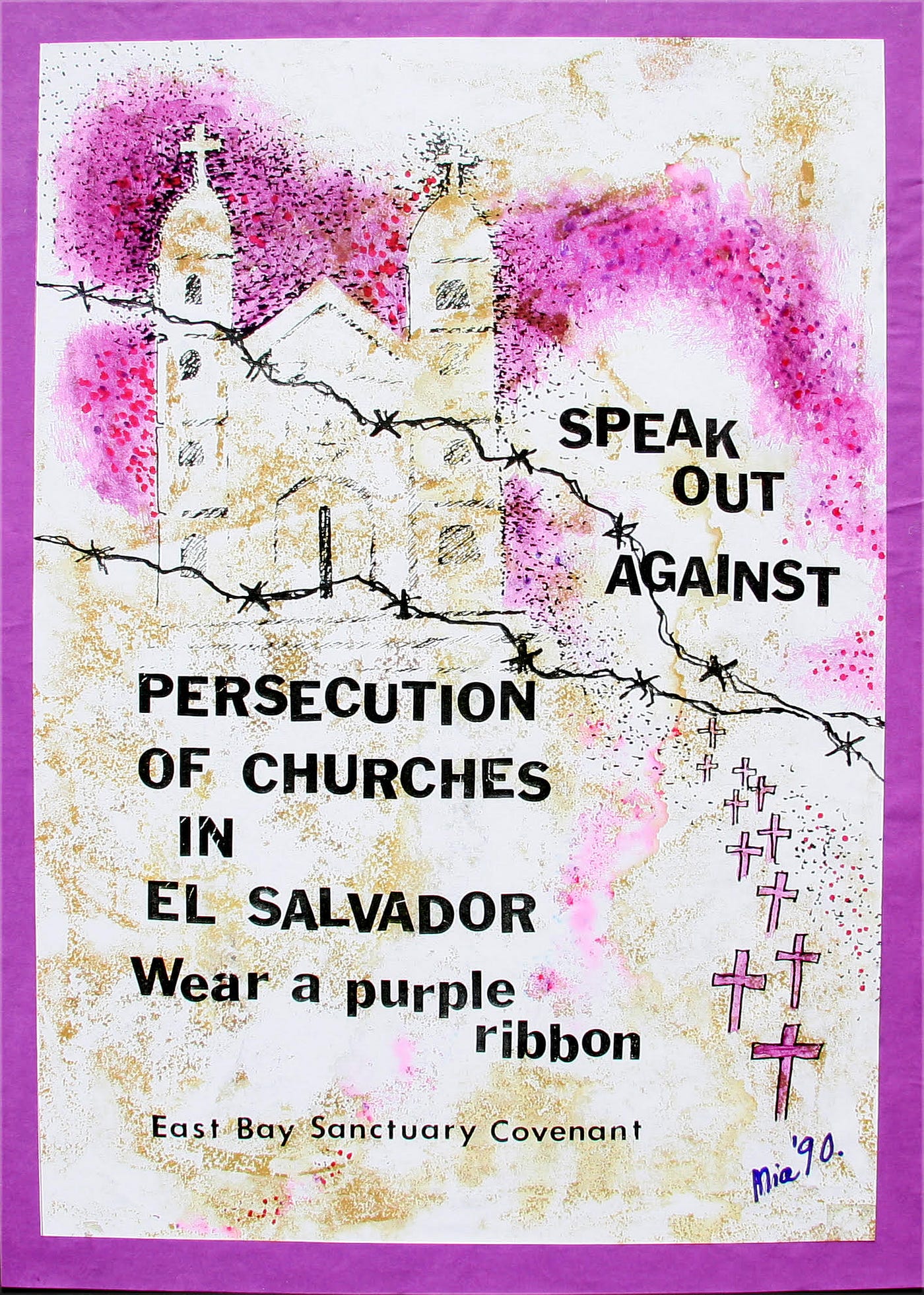

In Berkeley, however, local sanctuary advocates aren’t deterred. This includes the pioneering nonprofit East Bay Sanctuary Covenant (EBSC), a 37-year-old organization that offers sanctuary, solidarity, support, community organizing, advocacy and legal services to immigrants, asylum seekers, refugees and people escaping violence or persecution.

“Nobody can shut down sanctuary,” said Lisa Hoffman, development director at the EBSC. “Sanctuary is a commitment, a moral commitment to our values of recognizing the inherent human dignity and worth of every person. It’s a matter of conscience. It’s something that’s existed throughout time.”

Its history, as you now know, stems back much further than the Trump presidency. Since the initial resolution in 1971, Berkeley has passed nine additional resolutions, including sanctuary for Arab immigrants in 1991, a Hate-Free Zone in 2001, opposition to the Patriot Act in 2002 and the reaffirmation of Berkeley as a City of Refuge in 2007. San Francisco joined Berkeley as a sanctuary city in 1989.

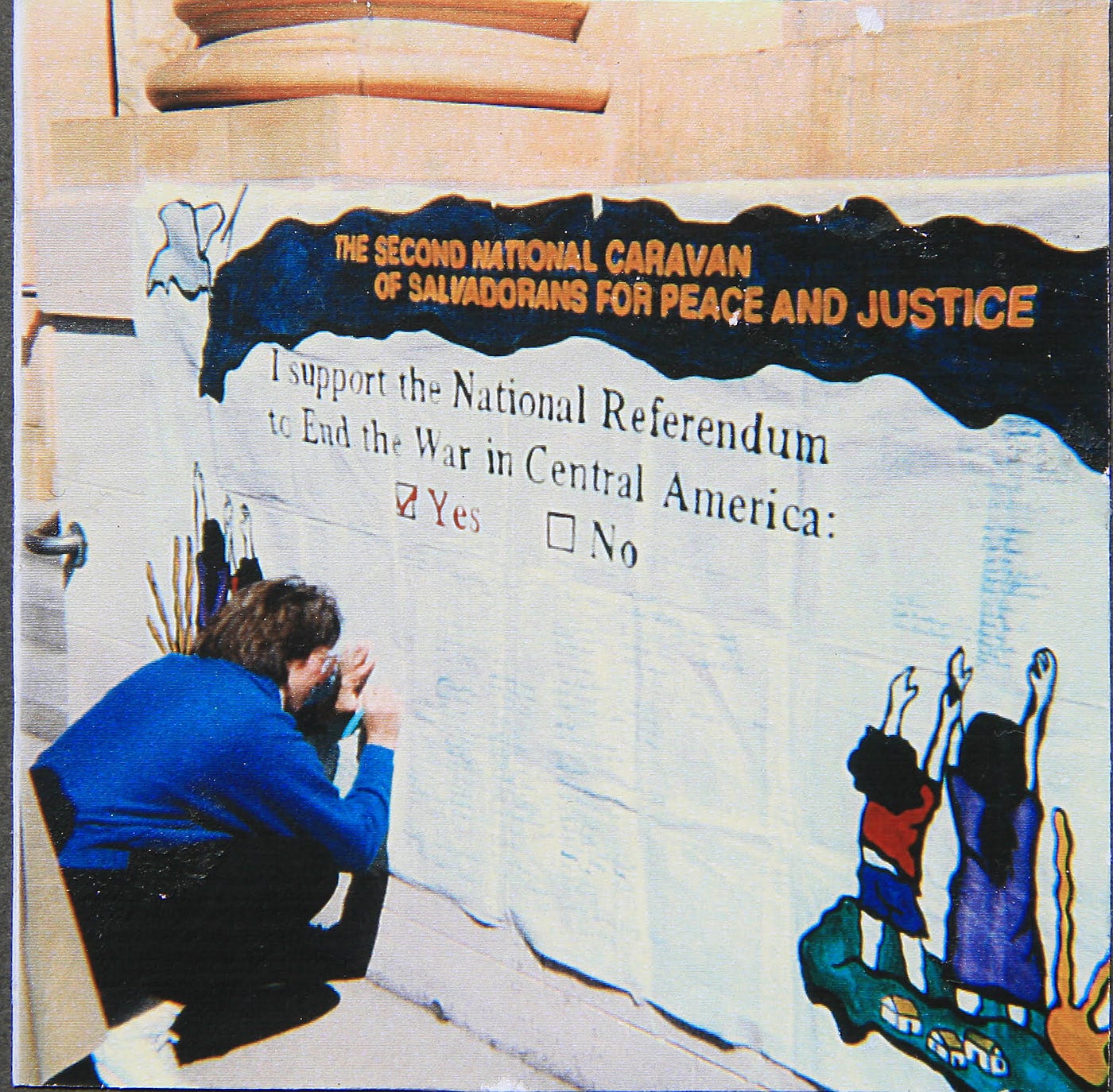

One of the largest movements, and the impetus for EBSC’s formation in 1982, was the exodus of tens of thousands of Central American refugees escaping violence and persecution in El Salvador and Guatemala in the early ’80s. In March 1982, five Bay Area congregations and one in Arizona declared their commitment to providing sanctuary for the 60,000 refugees. In May of that year, the newly established EBSC in Berkeley formed a delegation of US citizens who visited refugee camps in person in Honduras, El Salvador and Southern Mexico, as well as at the Mexican border, where refugees were detained.

“I think there is misunderstanding, because people either don’t have the education or the media isn’t giving them the truth, but the majority of immigrants are good people.”

Manuel de Paz, a Bay Area resident and the director of community development and education at the EBSC, lived through the terror of the civil war in El Salvador firsthand. Twenty of his relatives were murdered, including two of his brothers and his sister.

He talked about his experience with the East Bay publication the Monthly in 2007: “If you had a neighbor and he didn’t like you, he could report you, and the government would just come and kill you and your whole family.” After fleeing to the mountains and traveling day and night across Guatemala and Mexico, de Paz eventually arrived in the US, where his older brother already lived. His brother connected him with the EBSC.

Decades later, de Paz is now a US citizen and works full-time with the organization, helping other refugees and immigrants along their own journeys. EBSC’s current campaigns are focused on helping individuals under Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and Dreamers to achieve permanent residency.

“I think there is misunderstanding, because people either don’t have the education or the media isn’t giving them the truth, but the majority of immigrants are good people,” said de Paz. “In my experience at the office, in the case of DACA and TPS people, they are people who are independent. They don’t need money from the government. They are the ones who are paying taxes. They work hard; they go to church; they go to school; they have good jobs; and they have businesses. They assimilate into the culture.”

Hoffman has been involved with the EBSC since 2017 but has spent over two decades helping asylum seekers, including LGBT asylum seekers from the former Soviet Union, and volunteering briefly for a legal-services organization to help women and children asylum seekers in a detention center in Texas. Hoffman returned to the Bay Area and began volunteering with the EBSC in 2017. She is now working for the organization part-time.

“When I was [in Texas], my heart and mind really blew open,” said Hoffman. “I’m a relatively informed person, but I really had no idea of the tragedy that was going on and what these women and children were enduring, both in terms of the horrific violence they were experiencing and the conditions they experienced when they arrived in the US.”

Hoffman returned to the Bay Area and began volunteering with the EBSC in 2017, and now works for the organization full-time.

The EBSC’s work is funded by several major foundations as well as donations, and encompasses thousands of clients from over 60 countries. Hoffman said Berkeley was an early model for sanctuary cities around the country and continues to be a leader in the movement.

“People do not flee their homes unless they’re desperate.”

During the past two years, however, both Hoffman and de Paz say the Trump administration’s opposition to the sanctuary movement and a general increased focus on immigration have impacted their work. For Hoffman, the current political climate only underscores what she calls a collective responsibility to “listen and learn.”

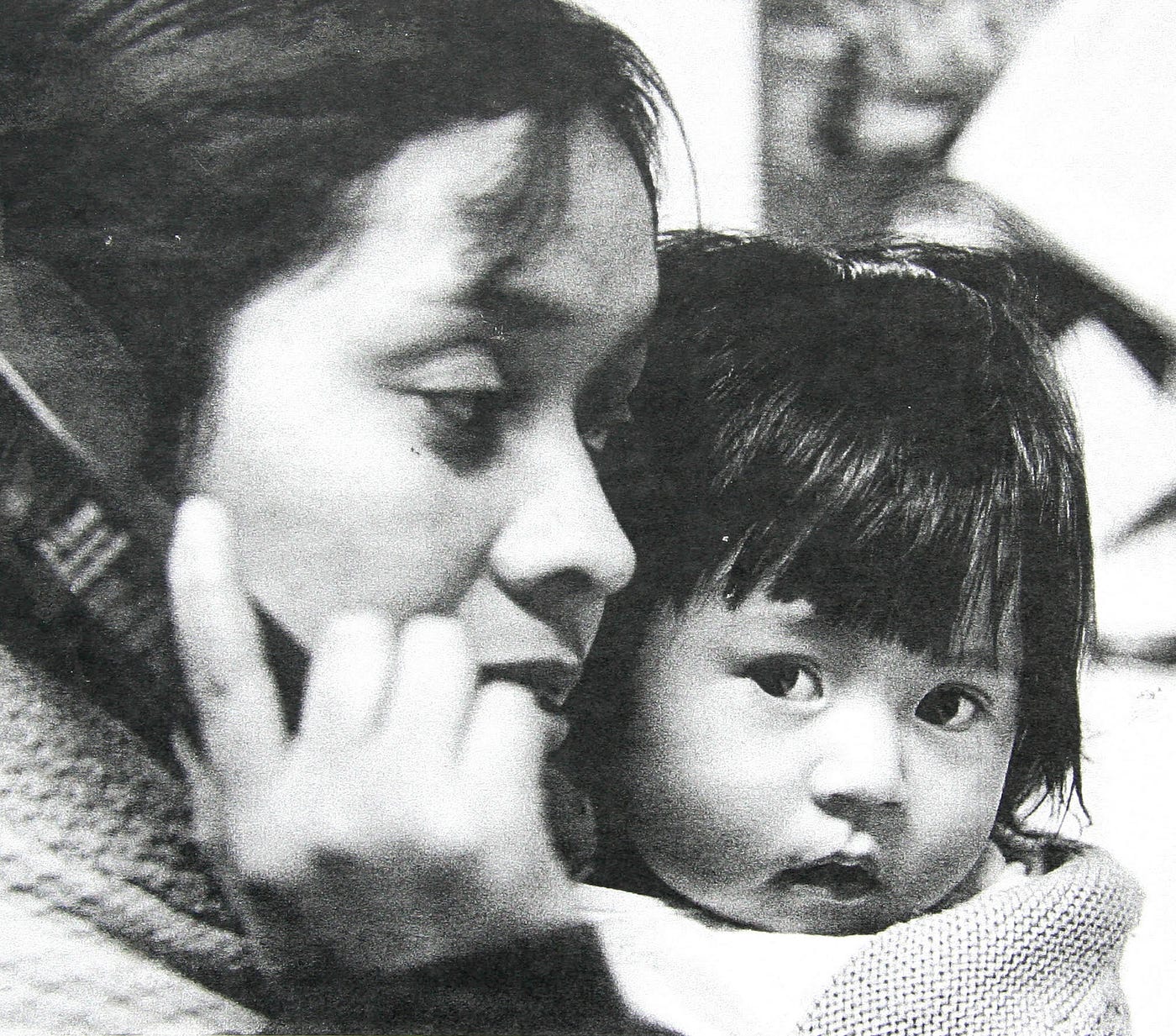

“We’ve seen an increase in the numbers of people seeking our services,” said Hoffman. “We’re seeing more unaccompanied minors who are making the treacherous journey on their own. People do not flee their homes unless they’re desperate.”

And de Paz, too, has noticed the effect the national conversation is having on immigrant and refugee communities here in the Bay Area.

“I think people are more afraid,” he said. “We can feel the stress in the community as well as in the staff who are working here.”

This came to a head in November 2018, nearly 47 years to the day since Berkeley passed its first sanctuary resolution. In response to reports that a caravan of thousands of people were nearing the southwest US border, President Trump signed a proclamation banning migrants from applying for asylum if they did not request it at a legal checkpoint. This new rule was in opposition to “longstanding asylum laws that ensure people fleeing persecution can seek safety in the United States, regardless of how they entered the country.”

In response, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Constitutional Rights and the SPLC filed a lawsuit on behalf of the EBSC and other plaintiffs—East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Trump. Shortly after, a federal judge ruled in favor of the EBSC. In December, the US Supreme Court upheld the block on Trump’s asylum ban.

Their work, however, is not over. Hoffman believes the EBSC and the larger sanctuary movement are just as important as ever.

“I have friends who say, ‘I don’t know if we can put the toothpaste back in the tube,’” Hoffman said. “Well, it’s not out yet. It ends up being a question of values and the kind of world we want to live in. Each of us needs to speak up in every way we can.”