For many years, every summer, my brother Chuck and I would backpack over the High Sierra for up to a week. Strong blood ties aside, we possessed diametrically opposed politics, lifestyles, and to some extent, ideas on backcountry etiquette.

Yet wilderness survival is a sort of bonding ritual, even for enemies, even for quarrelsome siblings.

One fateful summer, we were doing a favorite route, the Rae Lakes Loop. The trail laces the southern Sierra, the loftiest part of the Range of Light, with most of the shiny, snow-laden peaks over 14,000 feet, including Mount Whitney, the Roof of the Lower Forty-Eight.

We had made our share of mistakes on our debut trek years before — carried too much food, not filled our water bottles before a long dry stretch that nearly dehydrated us. Our Whisper Lite cook stove was the wrong model and its pump failed us at altitude. So we had no hot water, hence no morning coffee, a terrible mistake that shall never be repeated.

We had also made the acquaintance of one Ursus americanus, the scientific name for black bears, at one campsite. This cub, all chestnut and sleek, would pad up a steep slope until we made noise to scare him, then noiselessly return, still curious. He kept returning, sniffing, even though the nearby meadow was a pantry of wild food — pale blue elderberries, huckleberries, and Sierra currants.

Our last full day was one hell of a long one, during which we donned all our raingear and prayed that our backpack frames didn’t act as conducting rods as we dodged lightning bolts. We reached Junction Meadow along Bubbs Creek for our last night’s campsite during a break in the rain.

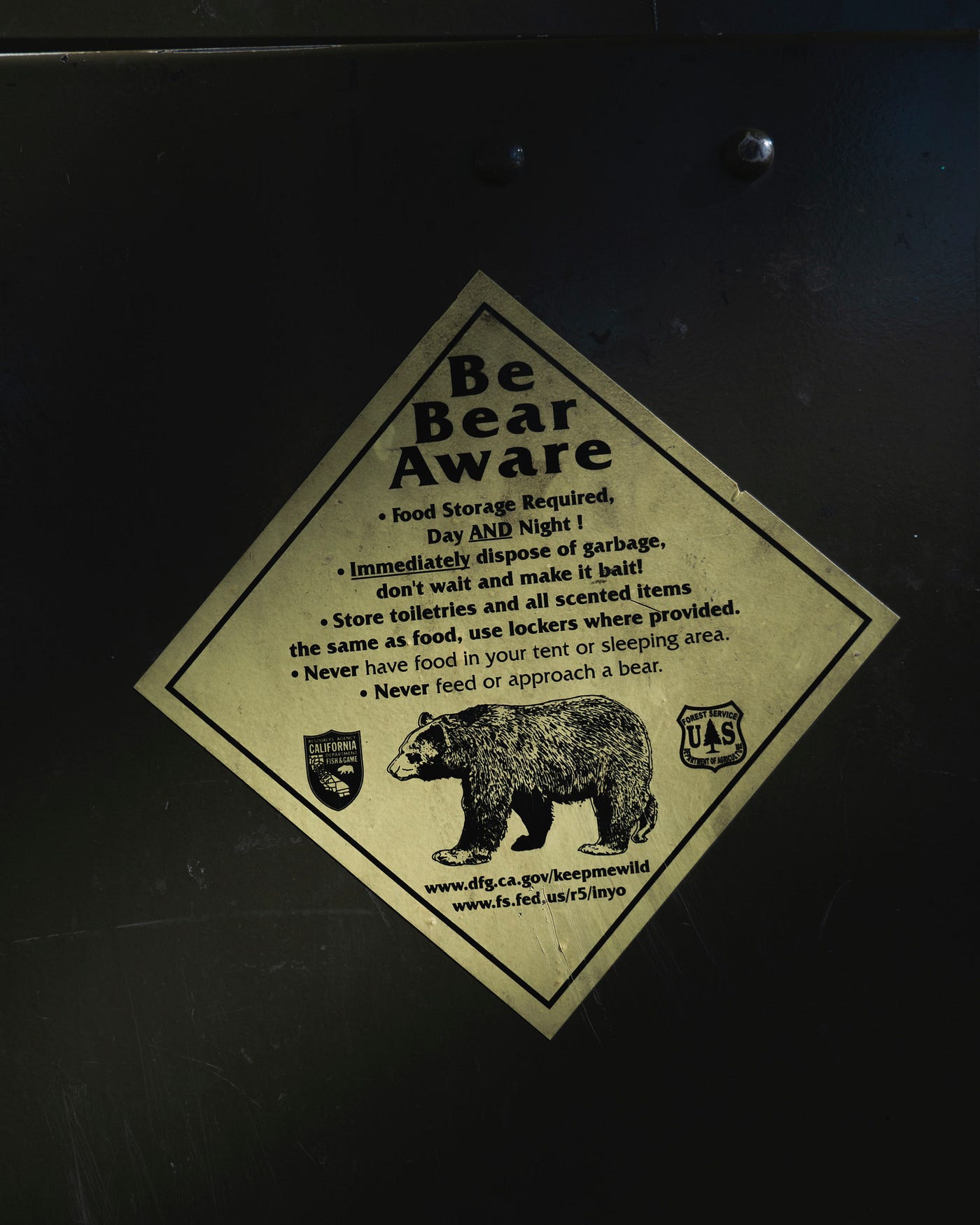

“There were bear boxes here last time,” Chuck said with the sangfroid of Henry Stanley greeting Dr. Livingston. We had just spent more than half the hours in a day hiking some 20 rigorous miles— 20 rocky-path, altitudinous, extra-long mountain miles.

“Park service wants you to call ’em ‘food storage’ boxes,” I said, equally dispassionate about our day’s accomplishment.

“I don’t care if you call them jack-squat boxes My legs are so beat, they think the dirt caked on them is doing the walking.”

“Yeah? Well, I’m so exhausted even my sweat is complaining.”

“Tell me about it.”

“I just did.”

Our movement was as circular and aimless as our conversation. We were in blood-sugar-deficit and perhaps our senses were impaired. We stopped and stood at the edge of the very high Bubbs Creek, scanning the far banks for the telltale orange of bear, or jack-squat, boxes. It’s not like the Park Service, an arm of our federal steward of the land, Department of the Interior, to put obstacles like rivers between you and the boxes. But, at that moment that was what we knew they had done. Just to add to our day’s hardship.

“Bridge must’ve been washed out by the storm,” Chuck said.

“Yeah, must’ve. No way to cross this.”

But Chuck was already trying to walk across the creek that rushed up his thighs. He leaned steadily into his $200 adjustable walking sticks for security.

“Where you going?” I asked.

“Where’s it look like I’m going?”

“Is that a rhetorical question?”

“Does it sound like one?”

I stepped in the white water to follow my big brother. “People die doing this every year,” I said. The water was powerful and moving at least 50 mph, maybe 150 mph, for all I could gauge. Chuck turned around to retreat back up the bank. I turned to follow. Then, it happened really fast — Chuck slipped on a slimy rock and fell and was bathed up to his shoulders in the rushing water. And, somehow — the power of his suggestion? — I slipped too and got soaked up to my neck. We climbed to safe ground and watched in silence as both of his expensive walking sticks floated like toothpicks down the flume of furious white water, forever out of our sight. Somewhere in a reservoir of the Central Valley Project in the San Joaquin Valley would be their graveyard.

“Shit,” we cursed in tandem, briefly united against a cruel force of nature.

“I fell . . . I was trying to grab your sticks,” I said, shaking the water out of my deep pockets.

“Yeah . . . why didn’t you grab them. I was trying to hand them . . . to help you,” he said sloshing away from the creek.

“Why’d you throw them in?”

“I didn’t throw them in . . . I was trying to give you one to hold on to.”

To this day his version of the story goes, “Yeah, I was trying to save my sister from drowning in this raging river when I lost these sticks . . best walking sticks I ever had.”

Oh, the revisionist history I have to endure.

“Where could those bear boxes be?” I said.

“Let’s skip it — we’ll just hang the food or something.”

“. . . Fine with me.”

We changed into dry clothes, set up the tent, camp, and cooked our dinner, some dried concoction that was worth its weight more for warmth and ritual than for gustatory delight. It was a gorgeous, lush meadow and the charm of the trip was restored briefly by the singing of Bubbs Creek.

Chuck was sprawled out on his cushy ground pad — a full-length one. Mine was a skimpier three-quarters length. I’m sure we had argued, somewhere along the line, about the merits and demerits of both.

“Well at least we’re clean,” I said.

“Yeah, and it doesn’t look like rain tonight.”

We were sated enough to count blessings. And to ignore the 900-pound gorilla: where to stash our food for the night? There were no proper trees for doing the counter-balance hanging system. They were tall, but their limbs didn’t extend far enough from their trunks.

We had heard that wedging it between boulders sometimes works. So like little kids hiding contraband goods from parents, we found a haunch of granite with a deep crevice that we imagined, in our deluded state, to be the most clandestine slot in the forest.

We ceremoniously wrapped and wedged between granite boulders our remaining food, which included my precious coffee, and our energy food for the last 14 miles. We mustered enough energy to carry two heavy flat boulders to put on top of the wedged food. Together they probably weighed about 100 pounds. We placed our metal cooking pots on top of all, the standard forest alarm system, on the off chance that a bear might try to get our food as we soundly slept.

Exhausted, we climbed into our sleeping bags.

“I’m going to sleep like a lead balloon,” one of us, probably me, must have said.

“I’m gonna sleep like a dead door nail,” the other must’ve reported back.

But again that gurgling creek, which I have since decided is haunted, power-tossed rocks and boulders and tyrannized me with a dozen auditory hallucinations from marching bands to angry crowds to cattle stampedes to Beethoven’s Ninth. At one point it mimicked a chorus of shrill voices crying, The bear! The bear!

Sleep came at brief intermissions. I dreamed I was back in our childhood home running up dark stairs away from some scary presence in the cellar. I dreamed my mother was percolating coffee and I smelled the aroma and heard the ping of the aluminum pot with the glass bubble top. I heard the aluminum pans again, hitting rock. I turned over, knowing my mother was near and all was right. Something was out there, I knew in my shallow sleep, but couldn’t we just sleep through it? Hadn’t we slept through loud parties, our brother’s rock ’n’ roll band . . . My mother banged the pot really hard.

And my brother, whose survival skills were honed in places far more treacherous than the forest, sounded a reveille.

Bears! Get up!

I jumped up, my heart racing like an engine whose idle needs resetting. It was 2 a.m. and pitch dark. Stars salted the sky and we could barely make out the tall Jeffrey and Ponderosa trees around us. We stood 10 feet from where the food was. Chuck shone his light. It was not a bear. Six golden yellow eyes bored holes in the night. We could decipher two cubs and the mother nearby, apparently prompting her kids.

“Oh, my God,” I said, “the mother is preparing them for a life of crime. Stealing human food!”

We both yelled to them to get out of there. But it was clear the cubs had a mission this night, sanctioned by an adult. I blew my whistle. We made enough of a racket to wake our dead grandparents. The rangers say this works. The rangers say lots of things. And my brother listens to them. But those three bears stood their ground. You want us to do what? they seemed to mock us.

Chuck, ever dutiful to authority, moved toward the food to get it away. “We are not allowed to let the bears have it,” he said as if he were about to take his toy back from a child.

“Are you crazy? Chuck, let the bears have the food,” I yelled.

“What about your coffee?” he said.

“Chuck, get the food. Quick!”

What took us 45 minutes to set up, the beasts had undone in seconds, with the swipe of a talon. The bears, at least having a dose of shyness, kept at bay as Chuck edged in and grabbed the food. Which was crazy. Bears are dangerous, especially cubs-cum-mama. But my brother Chuck had been in war zones, including Santo Domingo and Vietnam, and, even more scary, he had graduated from Dad’s Boot Camp.

The food bag was a mess, torn up by the bears who also slobbered over it. I’m here to tell you that a bear’s incisors cut through nylon and Ziploc plastic bags like a needle through hot wax. “We have to destroy this food or we’ll never get rid of them,” said Chuck.

Right.

“Let’s throw it into the river so the bears won’t get it either and be done with it.”

Right.

“The coffee, too.”

Wrong.

“I have to keep a little bit of coffee for my last morning,” I said stupidly. I knew it was stupid as soon as it was out of my mouth.

“You can’t, they’ll smell it and just keep coming back.”

“I’ll get a bad headache if I don’t have my Peet’s,” I whined.

But it wasn’t only the physical discomfort. My strong morning coffee, I reasoned, was my only vice. It wasn’t just the pharmacological effect of caffeine. It was the brewing, the blossoming aroma, the first sip, during which I ritualistically made noise as I sucked in the proper mixture of air to open my taste and olfactory apparatus to Mother Nature’s very own design for getting one chemically balanced to seize the day. It was my carpe diem. It was the very beverage our own mother, as maternal as the cubs’ mama, gave us in a bowl with hot milk at a very young age. The beverage that loosened our tongues, my five sisters’ and mine. How could I face the day without its soul-stirring energy? How could this guy be my brother and even suggest such a travesty?

While Chuck was throwing food systematically into a deep part of the creek, I fiddled around with my stuff and my sacred grounds. “OK, here goes the coffee,” I said, casting the wad into the creek. Gone, washed away. I made the sign of the cross.

For the second time in three years, at Junction Meadow, we had to hurry and break camp in the dead of night, this time while three bears watched our every move. As we hiked with our headlamps on, a thin moon cast some light through the trees and shone on something off to our left, not many paces from our site. Even in the dark, I detected its industrial orange paint. It was the oblong metal food storage box we had failed to find. If bears have any reasoning power, they must’ve wondered about ours. We went a good mile under starry heavens and found a spot of soft duff where we simply laid out our sleeping bags to catch a few hours of sleep.

“I smell coffee,” said Chuck when we were settled.

“What do you expect — it’s all over my hands from handling it,” I said. “Don’t worry.”

We fell out quickly but were up early and without breakfast tramped the 14 miles back to Cedar Grove. I offered to share one of my walking sticks with Chuck, but he refused. My caffeine-withdrawal headache pulsed along with the bunions on my hip bones and spurs on my trapezius muscles. It was a beautiful sunny day, but thanks to the rain and thunderstorms that spurred us on earlier in the trip, we had covered the trail a day faster than the first time.

I was staying the night at the Cedar Grove Lodge in Kings Canyon, so I told Chuck to take a shower there if he wanted to before the five-hour drive home to Los Angeles. But, once out of the woods he is always eager to get home to his wife.

“No thanks,” he said, “I’ll just call Cheri and have her get the hot tub ready for me.”

“Sounds great,” I said refraining from my usual dig about his L.A. lifestyle. We walked to his car and agreed it was another good trip, notwithstanding the bear incident.

He shuffled around in the parking lot and beamed, “You know, you can’t really appreciate simple things like pavement til you’ve done this type of trip.”

“Yeah,” I beamed back. “You’re right about that.” I marched my overused feet in place “Flat pavement. Feels great.”

“Yeah,” he said. “Another great trip.”

“Wonderful. Wait til Cheri hears the bear story.”

“Whose version?”

“Aw, g’head, you tell her yours.”

We hugged and he was gone. And I couldn’t wait to get out my stash and make my Sierra Dorada. I’d saved just enough and it would be richly rewarding and uncommonly smooth, to borrow the marketing pitch from a vice I don’t have.

I heated up some hot water with my camp stove, brewed it, noisily took my first sip — ahhhhhh — and sat down with a local paper. I read with great interest a story about a man leading a Sierra Club trip a week earlier on the same trail. Apparently, he had taken his food into his tent with him at night after a bear came snooping. The bear returned and reached into the tent hoping to abscond with the food and swiped the man’s scalp in the process, bad enough to call for an emergency exit from the wilderness.

Imagine that. I just sipped my joe and shook my head. Never, ever fight with the bear. That much, even I knew.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.