This article is part of SF Throwbacks, a feature series that tells the stories behind historic photos of San Francisco in order to learn more about our city’s past.

Just south of San Francisco lies the little town of Colma, home to 1,800 living residents, plus an additional 1.5 million who are dead.

With such a dead-to-living ratio, it’s no wonder Colma has garnered nicknames like “Cemetery City,” “City of the Silent,” and the “City of Souls.”

Even the town slogan gets in on it with a tongue-in-cheek nod: “It’s great to be alive in Colma!”

Any San Franciscan with roots going back a few generations likely has family buried in one of the 17 cemeteries throughout the tiny town. The number of famous people resting there — including Emperor Norton, Joe DiMaggio, and coffee heiress Abigail Folger — has helped turn Colma into an offbeat tourist destination. There’s even a pet cemetery that’s rumored to have Tina Turner’s dog in an unmarked grave.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

I’ve been visiting relatives resting there since childhood, but I rarely questioned why this part of the Bay Area was filled with seemingly endless rows of headstones. Didn’t every metropolis have a cemetery city?

Turns out the backstory of how Colma became a cemetery city is pretty interesting. (Hint: In typical San Francisco fashion, high property values pushed out the voiceless.)

Until 1900, San Francisco proper had four major cemeteries on what is now University of San Francisco land in the Inner Richmond. Today, only two cemeteries remain in the city: the San Francisco National Cemetery, located on federal land in the Presidio, and a small remainder of Mission Dolores Cemetery, which the Catholic Church saved on the basis of historical preservation.

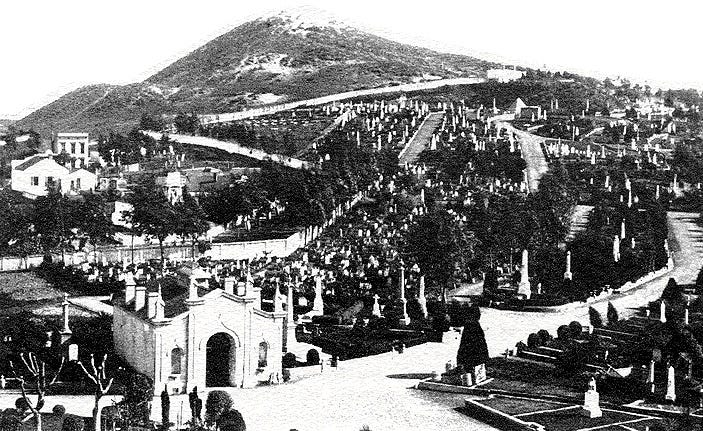

Since the city’s west side used to be a no-man’s land, many of San Francisco’s former cemeteries were concentrated there. There was Laurel Hill, pictured above, as well as Masonic Cemetery, Independent Order of Odd Fellows, and Calvary. Public dissatisfaction with the cemeteries became clear around 1880, a time when housing was quickly growing around them and streetcar lines had to weave around the plots.

As a result, San Francisco banned new burials in 1901. With no revenue from new clients, the cemeteries fell victim to neglect and became sites of robbery, vandalism, and taboo gatherings.

At that time, Colma — located near Daly City, south of San Francisco — was mostly farmland. Publications such as the Redwood City Times-Gazette note that the fog in Colma was good for growing cabbage, potatoes, and flowers. But in response to the growing city unrest in the 1880s, cemetery associations began buying up plots of land in Colma with a plan to repurpose the fertile soil for a different type of organic matter.

Mass exhumation of bodies from San Francisco cemeteries commenced in order to move several thousand remains. Some families had the means to pay the $10 fee for relocation, and some even had small processions to Colma. For those less fortunate, thousands of bodies were moved to unmarked graves.

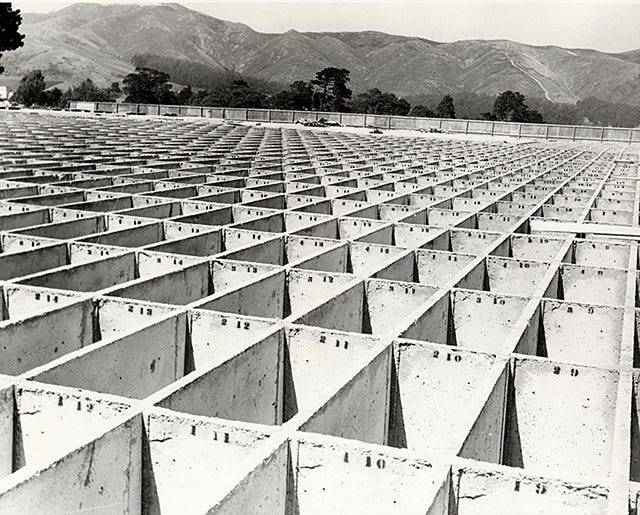

The construction of the new cemeteries was to be a long undertaking, as illustrated by the massive number of vaults pictured at just one cemetery.

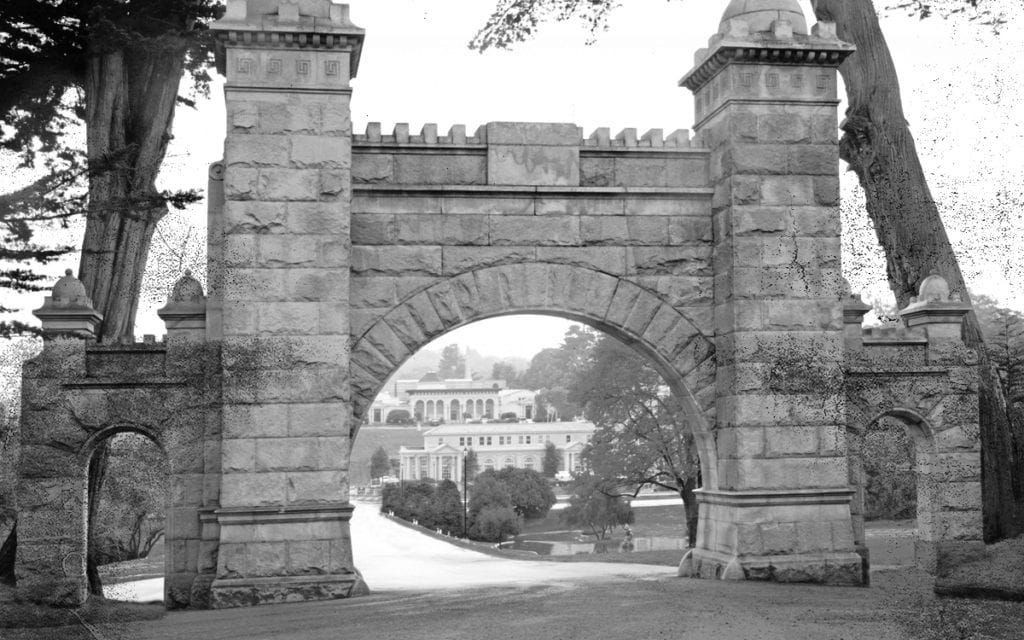

Cypress Lawn, built in 1892, is one of the bigger cemeteries in Colma. It is nondenominational and provides culturally appropriate services for a number of religions and cultures. There are also cemeteries designated for Catholic, Serbian, Chinese, Japanese, and Jewish people, all with their own designs.

The Brooks and Carey Saloon was built in 1883 to serve the cemetery construction workers. It was later called the Brooksville Hotel, and then renamed Molloy’s after being sold to Frank Molloy in 1929. The Molloy family still owns the bar today.

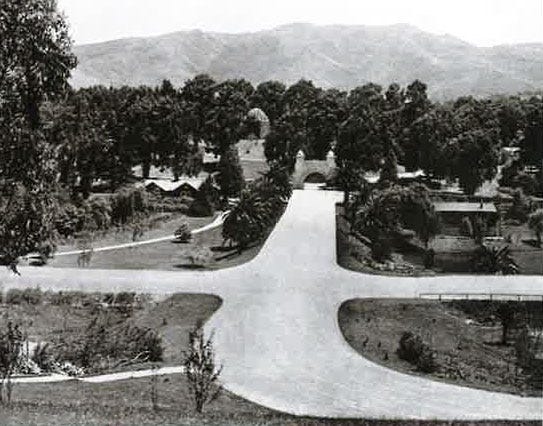

Pictured below is a streetcar stop located near the pub. Part of the train line, which was originally built for the residents and small businesses of Colma, was repurposed to transport coffins. Bay Area Rapid Transit later purchased the rail line for its Colma extension.

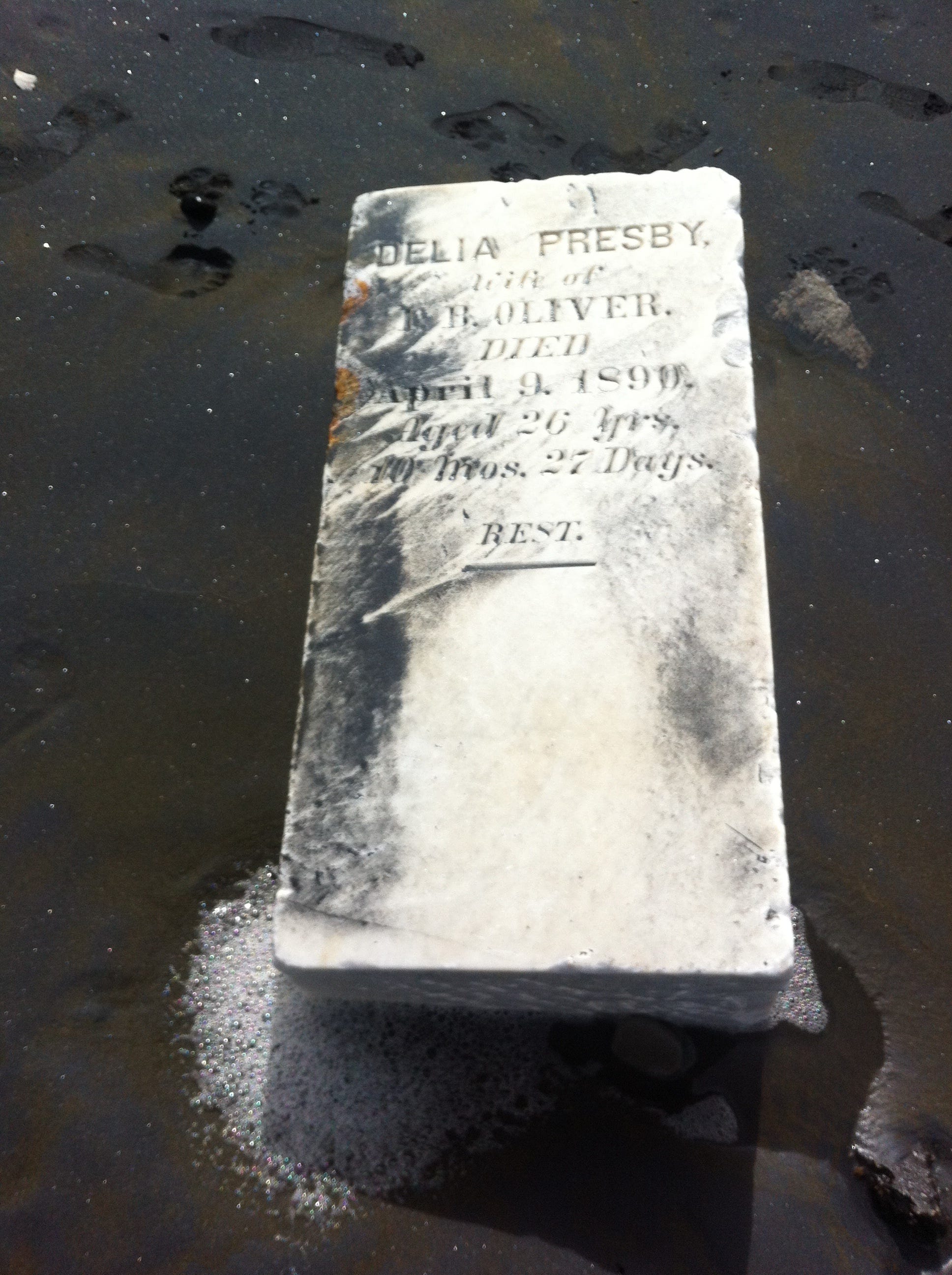

Because exhumations were done hastily and messily in some parts of the city, many grave markers and even bodies were left behind — some of which have been found in recent decades.

What started as a dumping ground for San Francisco’s dead has become a peaceful place of respect and contemplation, and even a tourist destination. However, as the overpopulation issue begins to echo in the afterlife, the City of Souls may have to expand into the surrounding abandoned land as its plots continue to fill up—or else get creative in celebrating passage to the next world in tiny spaces.