In some cities, up to half the land is owned by churches. How does notoriously irreligious San Francisco measure up?

San Francisco’s collective real estate is worth $180 billion. That equates to $2.1 billion in property taxes collected each year, money that goes to parks, schools and transit.

But religious organizations don’t pay property taxes; they qualify for what’s known as the “church exemption.” This exemption amounts to a subtle form of subsidization from taxpayers, who pay for the streets, sidewalks and infrastructure that make these churches’ existence possible. Moreover, property tax is one of the main ways that educational institutions are funded, including K–12 public schools, City College of San Francisco and SF State.

There are 528 “religious locations” in San Francisco, and the “average value” of a US church property is $1.7 million, so a conservative estimate puts the value of all church property in SF at around $900 million.

But since property values in San Francisco are much higher than the national average, this is almost certainly a lowball estimate. Indeed, the average sale price of a house in San Francisco is six times the national average. But when you dig into public databases to try to find church-property values in San Francisco, you immediately run into a problem: Proposition 13.

Prop 13 is a constitutional amendment that taxes property on the basis of its value when it was last sold, rather than its actual current value. Though it was marketed to voters as a means of staving off increasing property taxes for middle-class people — during a period in the 1970s when California real estate values were skyrocketing — many argue that its main function has been to serve as a tax loophole for the very wealthy, and to make housing scarcer by incentivizing corporate owners not to sell. Some argue that lost revenue from Prop 13 is the reason that California’s public-education system, once the envy of the world, has been slowly going down the shitter.

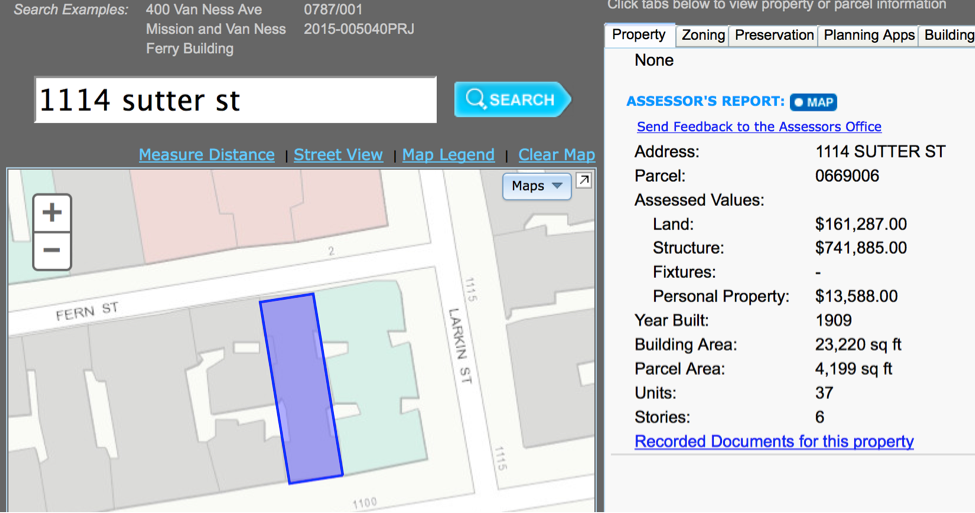

So when you try to search the San Francisco Planning Department’s maps to see how much a given church (or any other property) is worth, you don’t see its current assessed value, thanks to Prop 13. Instead, you see the value of the building the last time it changed hands. My old apartment at 1114 Sutter, a 37-unit, six-story building, has an “assessed” value of around $900,000 — a fraction of its actual 2015 value, likely in the tens of millions.

Even if the assessed value is way off, the Planning Department’s online tool does let you see the square footage of all properties in the city, including churches. The San Francisco Business Times reports that San Francisco office space in 2014 sold for around $750 per square foot. So I took a random sample of San Francisco churches, looked up their square footage, calculated their property value from that number and got an average of $4.9 million for my sample size. Multiplied by 528 churches, this comes out to about $2.9 billion in church-owned properties, which deprives San Francisco of $52 million in property-tax revenue.

What is the logic behind the religious exemption? Historically, the rationale was that churches performed some inherent social good and deserved not to be taxed. (As recently as 2012, an Oklahoma judge sentenced a drunk driver to 10 years of church attendance.) In today’s pluralistic world, the idea that churches are inherently good — and therefore deserve a tax break — is less convincing than it used to be. Many Californians were outraged at the outsized hand that the Mormon Church had in promoting Proposition 8 in 2008, which made gay marriage illegal until it was overturned in court in 2010. The Mormon Church’s “involvement […] was concealed under the façade of a coalition with Roman Catholics and evangelical Christians called the National Organization for Marriage,” writes Stephen Holden in the New York Times. “Mormons raised an estimated $22 million for the cause … [and] financed a sophisticated media barrage” to sway the vote. For the record, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has at least two buildings in San Francisco — the LDS church at 1900 Pacific, at 19,327 square feet, would be worth around $13 million according to today’s real estate prices, and hence it averts paying $234,000 a year in property taxes.

Likewise, 701 Montgomery, the iconic flatiron-shaped building in North Beach, is owned by the Church of Scientology — a tax-exempt religious organization whose controversies over the years surely don’t need repeating. Nonetheless, the building’s 25,395 square feet of office space would be valued at around $17 million, meaning that $306,000 per annum is missed in tax revenue.

This is not to say that religious organizations — Scientology included — don’t often have a positive effect on civics, ranging from feeding and clothing the homeless to providing them with showers. But there are plenty of reasons to question whether churches really should be tax exempt for billions of dollars of property in a city that could probably use the tax money to end the homeless crisis or break MUNI’s embarrassing record as the slowest public transit system.

Of course, if you think the religious exemption is unfair, you could always start your own religion and claim a tax exemption. An apocryphal story tells how the Universal Life Church, which will ordain anyone online for free, was created so that the founder could make his garage tax exempt. (It’s only half-true — founder Kirby Hensley did start the church in his garage, though it’s unclear if his main goal was tax savings). According to California state law, the courts have defined a “religion” as having the following elements:

— A belief, not necessarily referring to supernatural powers

— A cult involving a gregarious association openly expressing the belief

— A system of moral practice directly resulting from adherence to the belief

— An organization within the cult designed to observe the tenets of the belief

— The content of a religious belief is not a matter of government concern. Neither the county nor the state should question the validity of a religious belief

That’s pretty vague. You might argue that this definition could apply to some of the cult-like Silicon Valley tech companies. Of course, those companies have their own means of avoiding taxation without having to (formally) declare themselves a religion.