As a 17-year-old at Oakland Technical High School, I was required to complete a senior research project in order to graduate. Daunted by the high stakes, yearlong assignment, my advisor, Ms. Maureen Nixon-Holtan, and my senior English teacher, Mr. Brennan Nicholas, assured me that all I needed to start was to think of a question that I really, really wanted to know the answer to.

What I landed on: Why do teachers choose to work in Oakland?

With the clear inequity that exists between Oakland schools and the city’s surrounding districts — something I had been acutely aware of for years — I truly wondered why anyone would choose to work here when they could make more money over the bridge or on the other side of the tunnel. The project, though rooted in data about inequities, really came down to listening to teachers’ stories. Each educator had their own unique reasons to stay, but there was an intertwining theme: their ineffable love for Oakland kids.

The decision to return to the Oakland school district isn’t easy for many to do — financially or practically. Every year, one in five teachers leaves the district.

That was just over a decade ago. Now, I’m in my fourth year of teaching English at Oakland High School, understanding more than ever what my teachers meant back then. My love for my students is what keeps me coming back at the end of each summer.

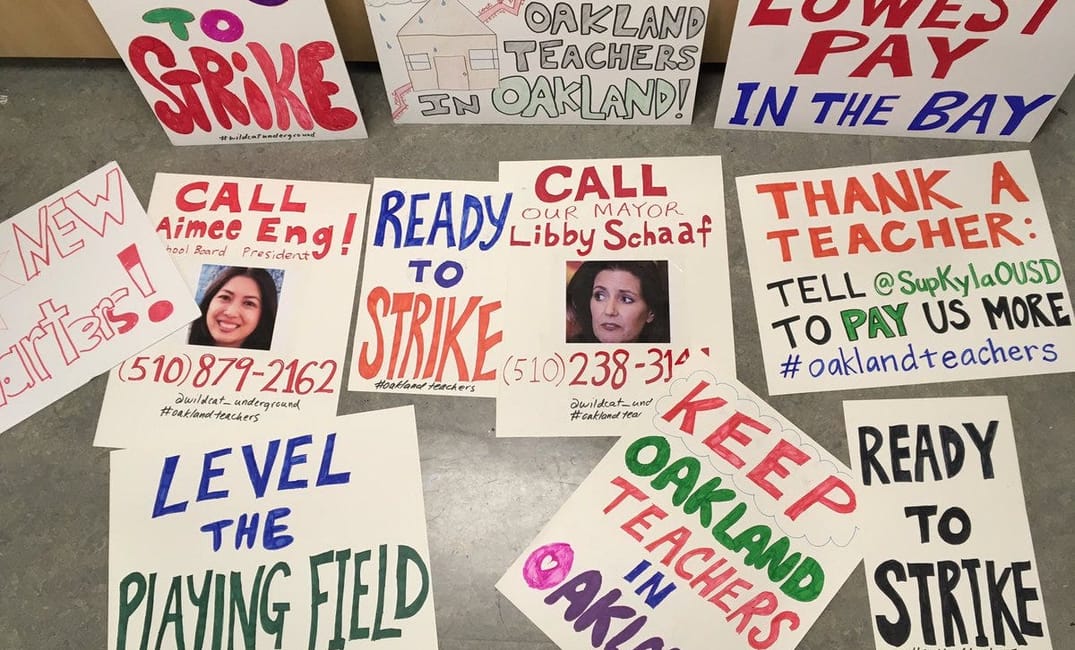

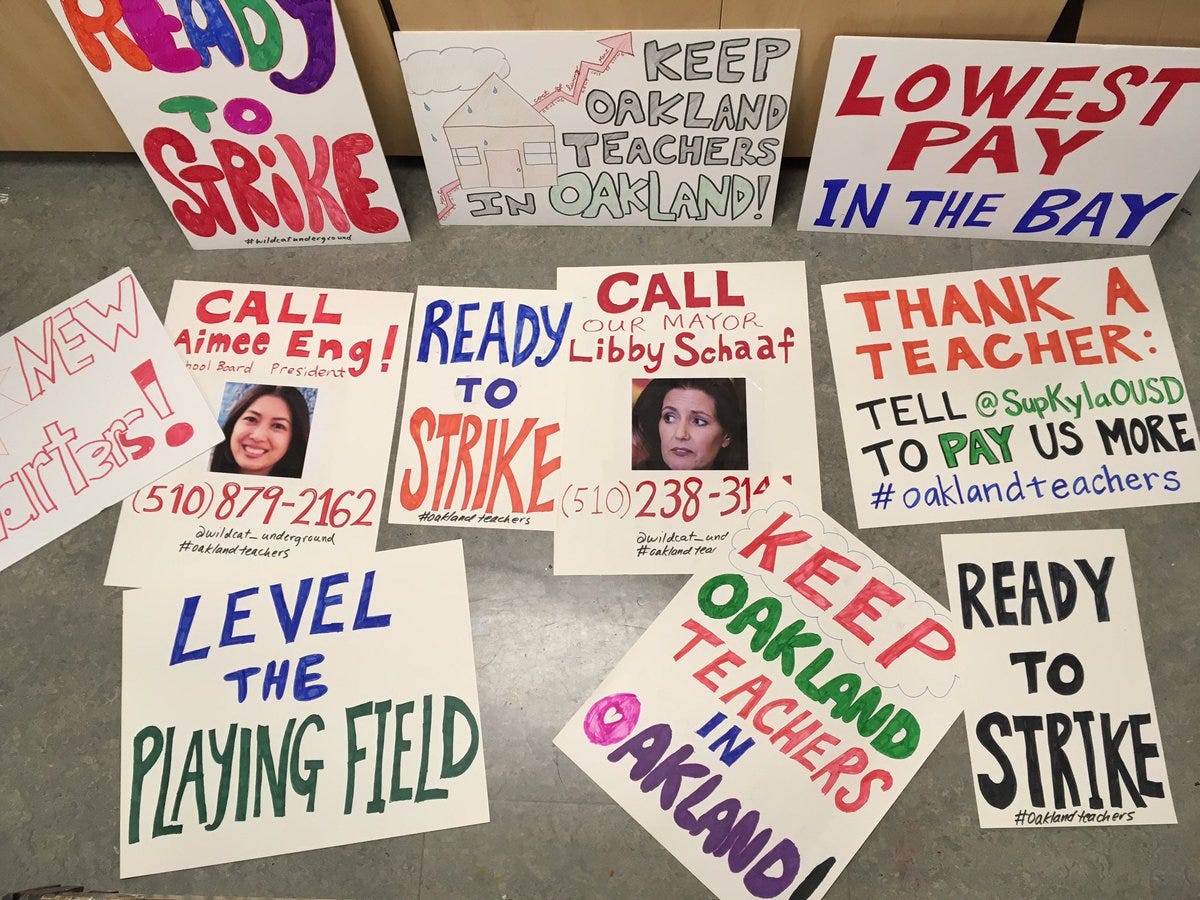

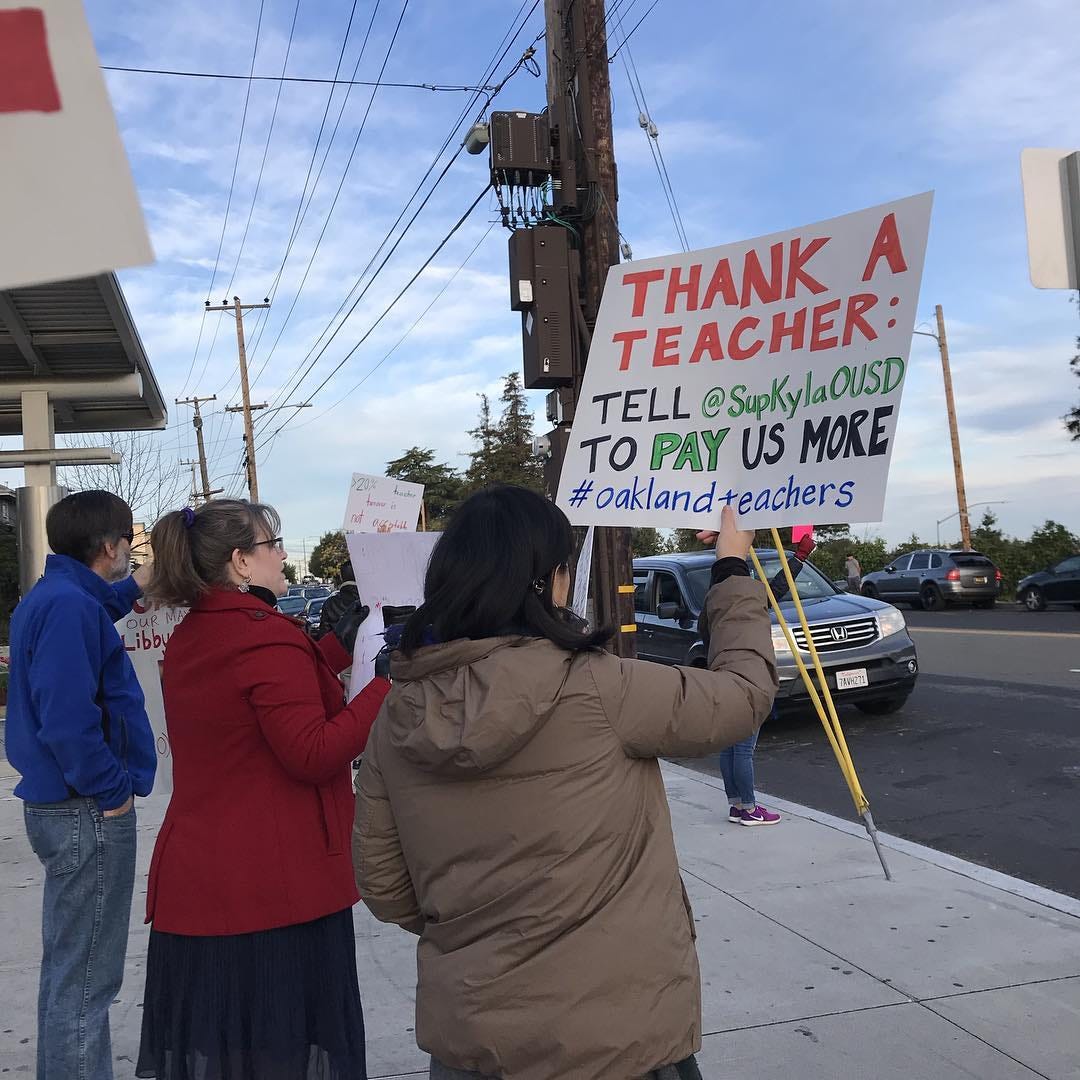

But the decision to return to the Oakland school district isn’t easy for many to do—financially or practically. Every year, one in five teachers leaves the district. The reasons for that are plentiful, but a top one is low pay in a city with astronomically rising prices. That’s why today, along with many of my fellow teachers, I’m participating in a wildcat walkout to warn the district that we need serious negotiations, or else we are committed to striking.

Since July of last year, Oakland teachers have been working with an expired contract due to ongoing negotiations resulting from the district’s failure to award us a decent pay increase (we were willing to settle for 12 percent, but they only offered with 5 percent).

I have lived in six different housing scenarios over the past five years out of economic necessity (as opposed to what many might assume to be Millennial whimsy.)

Similar action is being taken in the streets of Los Angeles, where 30,000 educators are striking. For many who have seen these teachers walk out on TV, it’s easy to understand what they’re asking for, but harder to truly understand what has led us to this point.

For me, even though I grew up in Oakland and still have family here, like many people my age, I struggle profoundly with housing instability. I have lived in six different housing scenarios over the past five years out of economic necessity (as opposed to what many might assume to be Millennial whimsy.) When I first started my credential program at San Francisco State University, I was forcibly displaced by a profit-motivated landlord, which meant I spent the first weeks of learning how to be an educator couch-surfing at friends’ places.

I’ve squeezed into a studio apartment with a partner over 45 minutes away from where I worked and across a six-dollar-toll bridge. I’ve lived in and been offered temporary short-term housing. I’ve spent over 50 percent of my monthly income on rent. (During that time, I tried to sell my beloved guitar to make ends meet, but the sympathetic music-shop employee behind the counter urged me to rethink, while kindly trying to assure me that everything would turn out OK.)

And even just before this past winter break, I came very close to living in a backyard trailer. As a December move-out date loomed, with no new apartment leads in sight, I began to open up to my students about my situation. Usually, I keep my hand close when it comes to divulging personal information with them, as I don’t like to add my problems to their own. But the stress around transitioning housing is so palpable, I couldn’t help but mention it.

One afternoon, a senior in my drama class asked me how my housing search was going, and when I told him about how relieved I was to have been offered access to a short-term trailer rental, narrowly avoiding another round of couch-surfing, he replied, “No teacher should have to live like that!”

Luckily, a friend and I found an apartment together at the last minute, but it was not without sacrifice. My commute has grown by 25 minutes, I had to re-home a pet, and my status as an Oakland resident expired, meaning I no longer get to share a city community with the students I serve.

On top of that, like many teachers across the country, I often pay out of pocket for classroom supplies, including snacks and school-supply basics for students. I work outside the limits of what is expected of me as outlined in our inadequate and outdated contract, not because I am a do-gooder or a martyr, but because my students need and deserve it.

The alarmingly high rate of teacher turnover in Oakland is not due to “bad kids” or twenty-somethings just “trying out” teaching as an experiment. It’s because the school district has failed to make investments in teachers’ salaries and student supports. Turnover in surrounding districts is not nearly as bad, because they have made those investments.

Within Alameda County, the Oakland Unified School District’s average teacher salary sits at $63,060 per year, nearly $10,000 less than the salaries of teachers in Albany and Alameda districts. We have the lowest starting salary in the county, as well as the lowest maximum possible salary teachers are able to earn after decades of teaching. When new, qualified teachers are researching job offers in the Bay Area, they notice these differences and make decisions based on them.

Oakland youth deserve nothing less than teachers who are valued and invested in.

As a senior in high school, I didn’t choose my research topic because I wanted to be a teacher. Like most teenagers, I truly had no idea what direction my life would take at the time. I was simply a kid who needed to hear that I was worth sacrificing for.

I needed to hear that I was worth teaching.

And my students today are worth teaching. They are worth the extra time, energy and resources — both emotional and economic.

Oakland youth deserve nothing less than teachers who are valued and invested in. They deserve district leaders who are responsible and transparent with our finances, who will make sure class sizes are small enough to allow for responsive relationships and who will make sure teachers are able to afford to live in the communities in which they teach.

My decision to strike, if and when the time comes to do so, is yet another iteration of the extra work I am willing to do on behalf of my students.

Oakland students are amazingly goofy, unique, dynamic and hungry for high-quality learning. The fact that they maintain persistently high expectations continues to impress me, considering they are the ones who have watched that revolving door of the teacher-retention crisis spin out of control for their entire primary and secondary careers. Despite witnessing one in every five teachers make the tough decision to pursue opportunities beyond the district, their optimism (while sometimes admittedly cynical in presentation) remains unshakable, and I admire them deeply for that.

The incredibly bright and passionate kids of Oakland deserve equally bright and passionate teachers — the best of the best, for the best of the best.

My decision to strike, if and when the time comes to do so, is yet another iteration of the extra work I am willing to do on behalf of my students. Oakland Unified School District must recognize that our teachers, alongside countless educators across the nation, are united and determined to fight, as our shared future is on the line.

They are worth it. We are worth it.