Something happened to rock music in the 1970s. Musicians presented themselves as equally enchanting and grotesque. Boys went onstage in glittering, sky-high heels; their hair feathered; their shirts shredded; and their lips smeared with rouge. Anarchist politics suddenly exploded, in which anti-government, anti-war sentiments were expressed in visceral, blood-boiling fashion. These changes resulted in the punk movement, a subculture that’s still mobilizing young people in the Bay Area today.

Over the course of more than 40 years since its official coinage, the punk community has evolved and amassed most of America’s fringe—especially in Oakland, where this subculture is thriving.

Punk isn’t just about music and aesthetics — it’s also about having compassion, integrity, and values, said Penelope Spheeris, the first filmmaker to ever document the punk movement in her iconic trilogy, The Decline of Western Civilization (though she’s perhaps better known for her initially underestimated yet wildly successful cult film Wayne’s World).

Spheeris notes that punk was revolutionary because it rejected capitalist, mainstream American culture. She views it as an essence, a quality that a person naturally possesses. “We’re not gonna shove that idea on somebody else like some cult or religion or some shit,” Spheeris says. “You either got it or you don’t.”

To find out what this Bay Area community looks like, I photographed and interviewed the many artists, organizers, and LGBTQIA+ individuals who are part of it. Ultimately, what I discovered is that whether you wear studs and spikes or look pretty in pink, identify within or without the gender binary, it doesn’t matter: Punk celebrates the outsider.

Partners Athena Polia and Nick Schneider

Athena Polia, freelance makeup artist and veterinary assistant, and Nick Schneider, plumber and occasional doorman at Eli’s Mile High Club, a popular dive bar in Oakland, met through Instagram.

Described by Polia as “a true Southern Texan,” Schneider exudes the wide-eyed enthusiasm of a young boy when he talks about their relationship, and how he fell in love with Polia. Through social media, they “wrote each other novels” and made their relationship official before even meeting in person. After the couple met face-to-face at Manic Relapse in 2018, a massive annual punk festival that takes place at the West Oakland skatepark, they moved in together.

After attending the festival together a year later, they both hopped the fence at the Piedmont Cemetery, where Schneider proposed. Despite that Schneider didn’t have a ring at the time, he asked Polia to marry him anyway since he couldn’t wait. “They said yes and we went to Kona Club [a tiki bar] down the street and got a shot together!” writes Schneider through Instagram.

An alluring figure both online and in-person, Polia has a distinct look that draws from 1980s subculture, such as the New Romantic movement, a cultural movement in the U.K. which combined visual elements of glam rock and the early romantic period of the 19th century (think Ziggy Stardust). Their makeup is also heavily influenced by German punk singer Nina Hagen and brazen color schemes — especially red and yellow. Polia joked that that can make them look like a bottle of Rush, which is typically used as an inhalant drug. “Goddammit!” they say, laughing.

Partners Autumn Carroll and Luna Spook

Luna Spook and her girlfriend, Autumn Carroll, also initially followed each other on Instagram, and have been together ever since meeting in person at a Pride party. Spook says there’s a queer punk scene unique to Oakland, which is why it attracts so many LGBTQIA+ punks from all over. “I feel like a lot of us here are in the Bay for certain reasons. Carroll is from Oakland, and she’s still here. I moved here because I wanted to be in a community like this,” she says.

It’s understandable why LGBTQIA+ punks gather in a liberal city. Carroll, a musician and sound engineer who’s trans, says that the general public still has trouble accepting her community. “People are weird about trans people,” Carroll says, especially in places like Bakersfield, where queer punks are prone to receiving stares—and where Spook and Carroll were about to go to visit Luna’s family for Thanksgiving.

According to Spheeris, who has extensively documented the community in California, many people didn’t accept punks when they first emerged — specifically “that straight, normal, kind of established-mainstream-kind-of-person that would shop at Rodeo Drive and just buy into the whole late-’70s Reagan era bullshit,” she says. “They were afraid of punks. I think we kind of enjoyed that. They needed the shit scared of them at that point, they were just like zombies.”

Alex Rueda, photographer

There are also many LGBTQIA+ punks in the area who document the community through their artistic practice. One of them is Alex Rueda, a genderqueer, San Francisco-based film photographer who covers Bay Area subculture — particularly in the punk and BDSM circuit. Rueda says they feel welcomed by other punks here, despite that the queer punk community is still relatively niche.

However, for Rueda, a former dominatrix, photography is more personal; it’s a means of memorializing friends lost within the punk/sex worker community — which is more fragile than it seems. Rueda has lost friends to addiction, HIV complications, suicide, and car accidents.

But according to Rueda, the dangerous aspects of punk are what make it exhilarating. “In [my] 10 years in the punk scene I’ve seen some crazy stuff,” they write through email. In “pits,” where people consensually push each other around at live shows, Rueda saw “people throwing bottles at the bands… fireworks being thrown… baby carriages being lit on fire… a vocalist tossing around a whip… my friend Chi even burned the American flag at his show this past week a foot away from people watching his band’s set.”

Myron Fung, music photographer

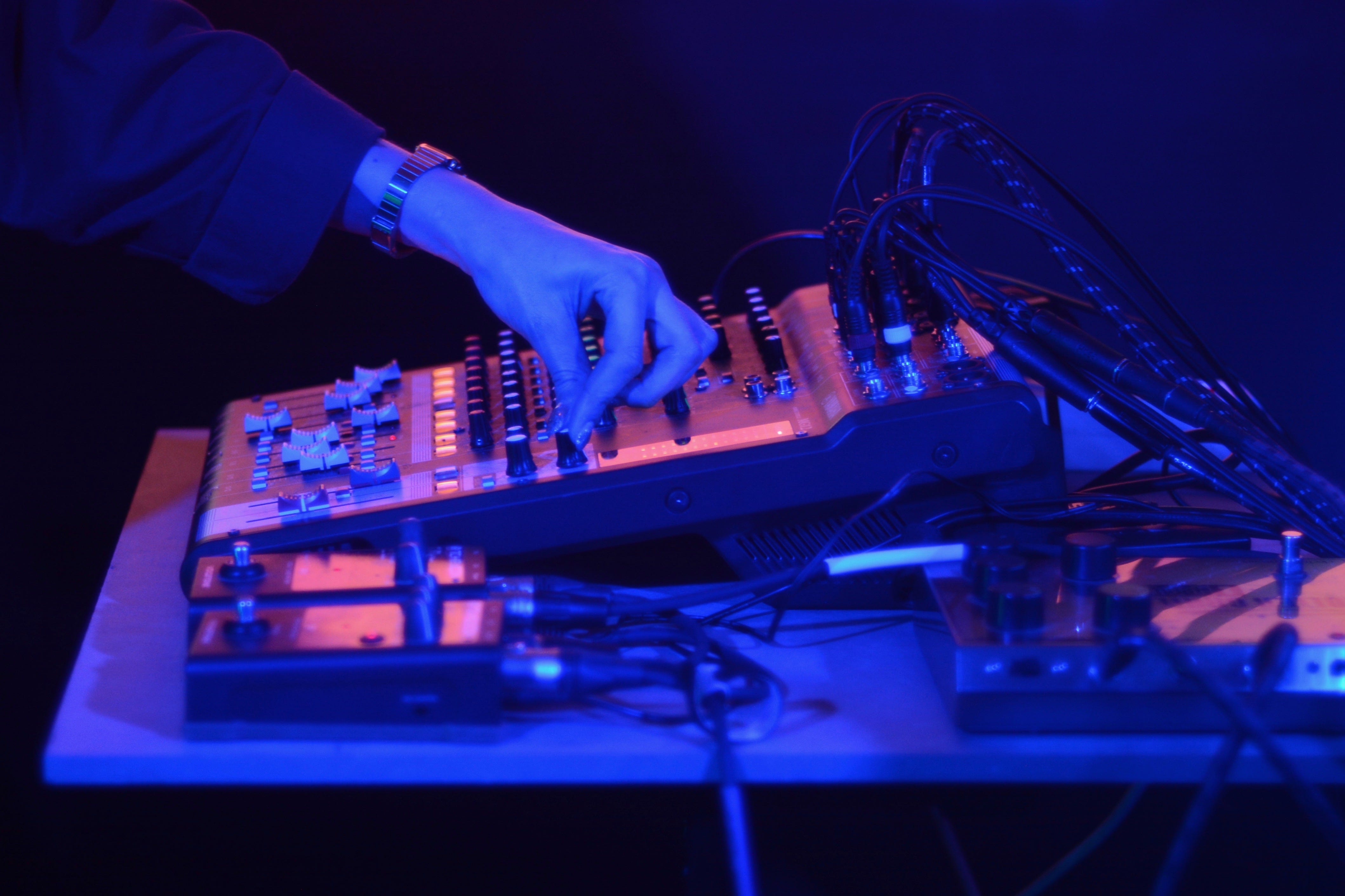

Myron Fung spends his time photographing Bay Area punk shows. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a backyard benefit, a rave under a West Oakland underpass, or a noise set at a vacant flower shop, Fung will be there to document it. And because of his fervid dedication to sharing and chronicling live music, Fung is an inimitable — and endearing — figure in the punk circuit.

Despite that he just bought his first camera in July of 2018, he’s taken more than 35,000 photos at more than 140 shows. A civic-minded photographer, Fung says that he’s happy when his images wind up on local bands’ cassettes or as zines. “I want to give bands the appreciation they deserve,” he says.

Though initially nervous about entering and photographing the punk scene, according to Spheeris, attending shows and looking the part isn’t what’s important—though some people certainly think that’s the case.

“There’s a lot of poseurs out there; I can smell them coming. They’re kinda funny,” she says. “They wanna look a certain way but don’t get what [punk] is all about — that it’s a philosophy and way of life with kindness, compassion, and integrity.”

Techie Blood, hardcore band

According to guitarist Trevor McBride, the band name Techie Blood refers to collective anger toward the tech industry and capitalism’s overarching effects on habitability—and the harmony of life itself. “It’s beyond just gentrification… we should all be hating it,” they say outside Tamarack, a cooperatively owned, collectively run bar and restaurant in downtown Oakland where they just performed. Proponents of education, McBride says that most of their band members are communist and politically left-leaning, and they’d personally rather have their audience read Lenin than listen to their music.

McBride also says that they can’t think of an Oakland punk band that doesn’t have queer members, and it makes sense why. “Not to say that [being queer] is easy, but our scene is blessed with acceptance… [punk music] has always been queer… it’s outsider music, it’s for freaks and losers and people who have been bullied.” And because of this, it begat a musical scene in Oakland full of “powerful and proud queer punks.”

Samuelito Cruz, independent record label owner

Oakland musicians are also keeping alternative music accessible through their own business ventures.

Samuelito Cruz, an independent record label owner, operates Smoking Room, which distributes Bay Area bands’ records, cassettes, band flyers, and screen printed “bootleg” band tees. Though he used to fulfill orders out of his bedroom, he recently expanded, and now mostly works out of a space in San Leandro. An inclusive label, genres distributed through Smoking Room include punk, indie, hardcore, “slow jams,” and R&B. As a musician himself, Cruz plays in Oakland bands Residue, Mop and Healer.

Will O’Connor, musician, electrician, and show organizer

For some, live music is an opportunity to mobilize and collaborate. Will O’Connor, a unionized electrician by trade, moonlights as a pro bono show and festival organizer in Oakland. Though he helps book bands for anarchic, high-octane music festivals like Manic Relapse—which attracts punks from all over the world—he also uses live music as a tool to benefit leftist causes.

Many local businesses are on board with this approach to music. On November 22, Tamarack, the restaurant and bar co-op, worked with O’Connor to book new-wave and post-punk bands for their Chilean Rebel Benefit—which subsequently raised $625 for community kitchens and street medical tents in Santiago. O’Connor says it’ll likely be the first of many musical benefits at the newly minted co-cop.

Spheeris lovingly referred to punk scenes as “termites in the woodwork of America.” And if America’s woodwork is a white picket fence, then Oakland punks welcome all to gently deconstruct it: through gender expression, anti-capitalist practices, and, perhaps most notably, compassion.

“When you’re around a lot of punks, they have a good set of moral ethics and you feel quite uplifted as opposed to my years in Hollywood, where people have zero ethics and they’re just a bunch of assholes,” she says.

From my interviews, I discovered the Oakland punk community is bold yet unpretentious, and many of its people radiate an energetic warmth that’s both uplifting and inspiring. And that’s when I finally understood what Spheeris meant when she said that certain people just have “it.”