“When it all started, no one knew what to expect, so we just plowed ahead like it was a normal year,” owner of Two Dog Farm Mark Bartle says of the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic. But Bartle, who also operates a stand at the Heart of the City Farmers’ Market in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, says it quickly became clear that closures of surrounding offices meant no workers to shop at the midweek market, and overall, a slew of regulations would change the way they did their business.

Throughout the pandemic, vendors like Bartle at the farmers market — open Wednesday and Saturday — have served as an essential service to a neighborhood that’s mainly low-income residents without access to a supermarket offering a slew of innovative programs to help those in need. This is true even as farmers have struggled through a combination of the pandemic and California’s devastating wildfire season.

“Heart of the City Farmers’ Market has served this community for 40 years and for the first time, we fear for the survival of this market,” says Kate Creps, Heart of the City’s executive director. “We’ve closed all nonessential programs to narrow our focus to providing food relief for a devastated neighborhood that lacks a supermarket and has limited access to fresh foods during this pandemic.”

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

Overall, the market (which has operated for the past 40 years) has lost over $100,000 in expected stall fee income. The market’s leadership reports that more than 50 vendors have had to reduce or suspend participation, while at least 16 have been forced out of business permanently. Those farms that are still able to participate, many of which are families and longtime vendors with Heart of the City, are cutting costs and working longer hours.

“We still have expenses,” says Isabelle Pardez of Paredez Farms, located in Tulare County. “We had to cut down on how many people were working on the farm. Along with the fires, it’s had a drastic impact on our livelihood. We travel five hours in one direction. We’ve been doing this for more than 30 years. I grew up out here.”

For Bartle of Two Dog Farm, the fact that his business is still operational is just short of a miracle: His family home and farm building structure burned down in the fires earlier this season. While the crops were preserved, the farm fell within the burn zone — so they had limited access to harvesting. They lost, for example, a month’s production of peppers.

A big part of their survival: their supporters. A GoFundMe for the farm has raised $33,000, helping Two Dog get back on their feet. While it’s not enough to recover everything lost to fire, Bartle is appreciative of what he has and still shows up at Heart of the City twice a week. “You have to roll with the punches and do what you can.”

With this year’s record-setting fire season in California, five of the 10 largest fires in California history happened in the past few months. San Francisco residents are acutely aware of their severity. In September the smoke from the wildfires was so thick that it obscured the sunlight. Market customers shopped for produce amid a deep orange haze.

Even in areas where the wildfires haven’t been active, their smoke has affected many farms throughout the state. Poli Yerena from Yerena Farms in Watsonville has been serving Heart of the City since it began in 1981, and also serves on its board of directors. Smoke has impacted his berries and tomatoes, in particular, leaving visible marks from the ash, an example of how pervasive the impacts of the wildfires are no matter how close a grower’s farm is to the fires themselves.

Amid the chaos the issues the smoke and fires brought up, Heart of the City has continued to operate. Farmers have learned how to adapt to selling food during a pandemic, including how to reconfigure the way they manage their stands. Before the pandemic, customers would select their own produce, sifting through piles of mushrooms, tomatoes, and onions for a preferred texture and ripeness. Now, everything is pre-bagged, and yellow caution tape separates customers from the food.

At Far West Fungi, a Bay-Area family-owned business that grows and sells mushrooms, additional staff are now sent to the stands to help with the transfer of food from the stand to the customer when a purchase is made. This is a new burden on the business and adds to concerns about their team’s safety and health. Sean Garrone, one of the four brothers who run the farm and a current Heart of the City board member, says that they’re taking all precautions, including gloves, masks, and social distancing.

While Covid-19 has affected sales and changed the usual layout of the farmers market, there are reasons to be optimistic. Garrone says that the boost from customers cooking at home more often has helped. This trend is as much a reflection of life during the pandemic as it is of the importance of farmers markets and grocery stores in the day-to-day lives of urban dwellers.

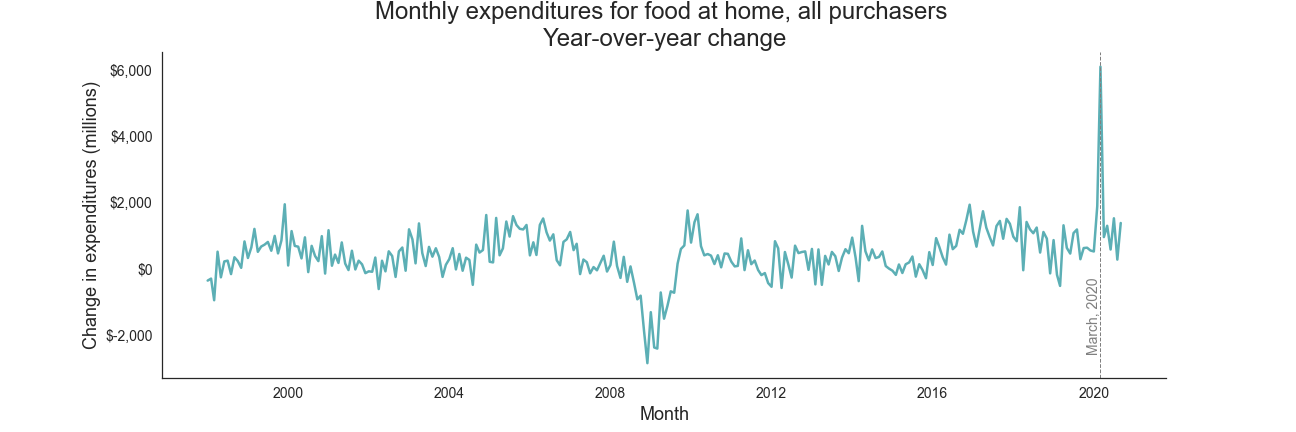

“We’re very fortunate that it was decided to keep these farmers markets open,” says Garrone. According to national data from the USDA, monthly sales for food consumed at home has increased since the start of the pandemic and shelter-in-place policies, while food purchased away from home is just now beginning to slowly recover.

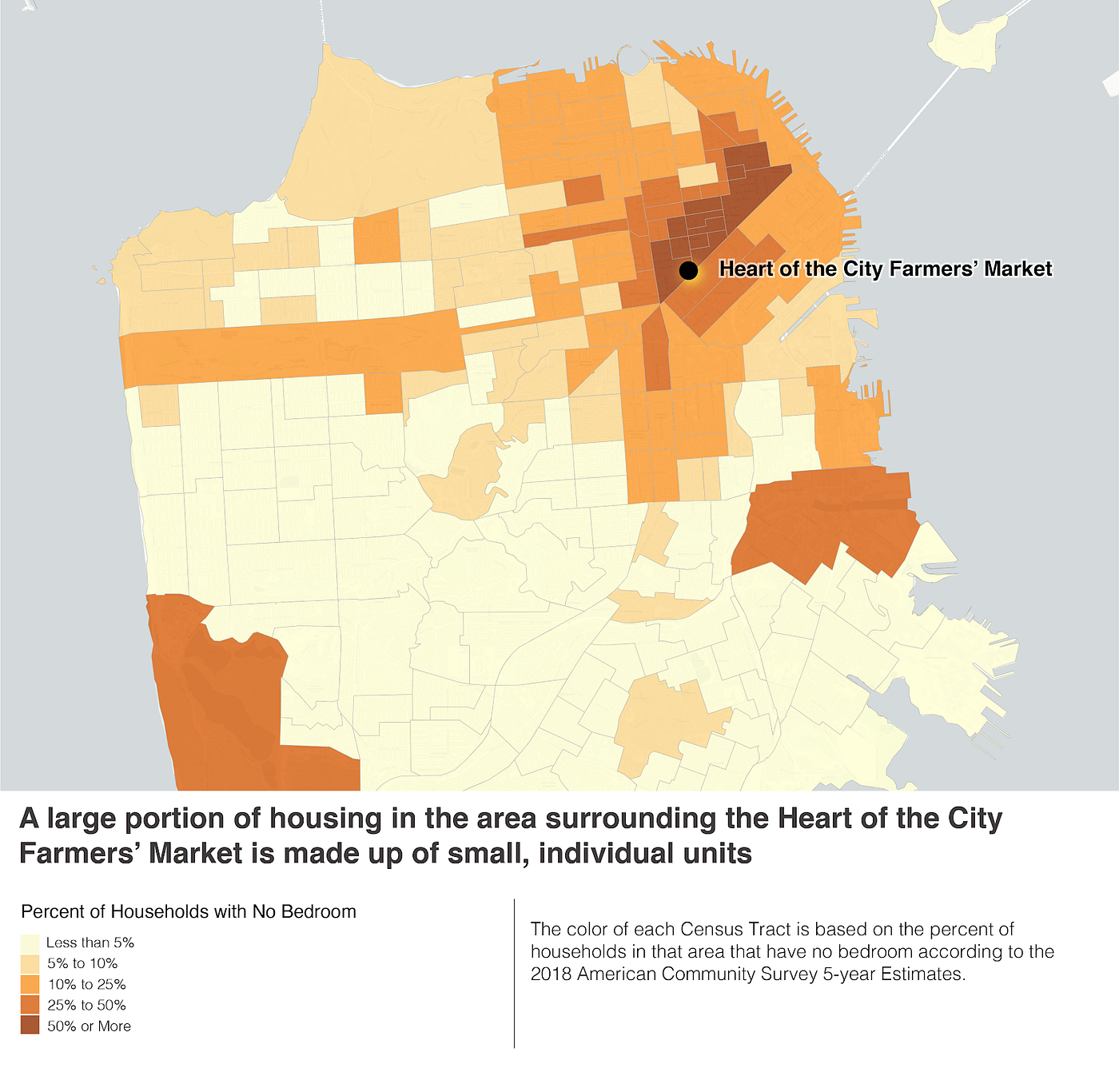

However, even as urban dwellers are cooking at home more, this may not be an option for many Heart of the City customers. With nearby offices closed, shoppers are predominantly residents of the surrounding neighborhoods, many of which are low-income. Housing in the area is largely single resident occupancy units with shared kitchen spaces, which face strict guidelines to prevent transmission of Covid-19 due to the increased risk their residents face. While Heart of the City provides access to fresh food for surrounding neighborhoods, it’s only one component of helping families prepare healthy food at home. Lack of kitchen space presents a significant barrier.

For Tony Mellow of Mellow’s Nursery and Farm, a Bay-Area-based family farm that produces a wide range of fruits, vegetables, and plants, frequently changing rules for vendors about handling produce have added friction and frustration. In an industry that requires months of planning ahead, these quick changes in guidance are difficult to manage. On top of this is the stress of bringing produce from crop to pallet. Farmworkers are essential to the supply chain of fresh food, and their work requires them to be on-site, which places them at the top of the list in terms of health risks. “Those who make the rules don’t know what the situation is out in the fields,” Mellow said.

While some farmers maintained a steady presence at the market, others were reluctant. Ken Phan of Ken Phan Farm, a local farm specializing in Vietnamese herbs, was nervous after the shelter-in-place announcements and new restrictions on the market. He paused his activity at the market during March, April, and May of this year. Even while he was taking a break from selling at the market, his farm was still producing, leading to a surplus of food he was unable to sell.

“I discounted, donated, gave away here and there. I took a loss for three months. No income, no nothing for three months,” he said. Since returning to the market, Phan has been able to bring in more income, but business has dropped by about 25%, and while he tried to apply for support through government stimulus programs, he was ultimately not able to navigate the complicated system. He reflected on the dilemma with empathy for other farmers who are struggling, “It is what it is. The same thing that happened to me has probably happened to a lot of people too,” he said.

Restrictions on cross-border travel between the U.S. and neighboring North American countries further complicated farmers’ operations. Muz Afzal from M.A. farms, a small farm specializing in seasonal fruits, and his family found themselves taking on more of the responsibilities than they normally would.

“We had issues finding workers this year,” he said. “Right when Covid hit and the season was starting, a lot of workers didn’t come in to work. It was me, my dad, and my sisters for the first three months of the season.”

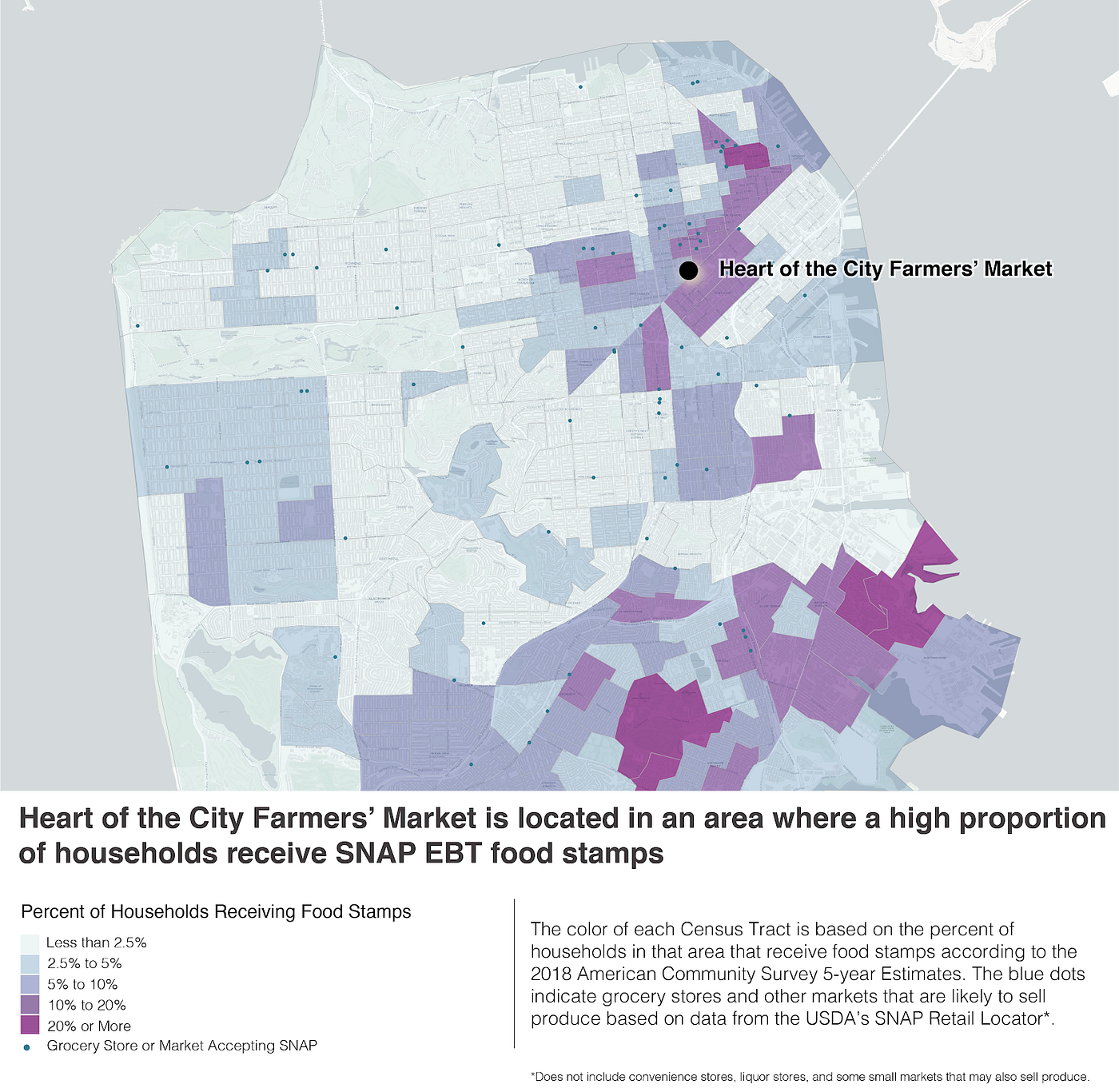

Overall, people are glad the market has remained. Located in an area that’s underserved by grocery stores and in which many rely upon food stamps, the farmers market provides a much-needed service. There is no supermarket within walking distance of the Tenderloin, and stores that accept food stamps are primarily made up of convenience and liquor stores that stock alcohol, junk food, and canned goods that, while they have long shelf lives, have limited nutritional value.

Heart of the City is dedicated to filling that gap. Through their support for small farms, they help make fresh food accessible for low-income customers who struggle to afford healthy food in a city with the highest cost of living in the nation. The organization minimizes operating costs to keep participation fees as low as possible for small farmers. The market has a flexible attendance policy, which means that vendors only need to pay their stall fees when they participate and have crops growing to sell.

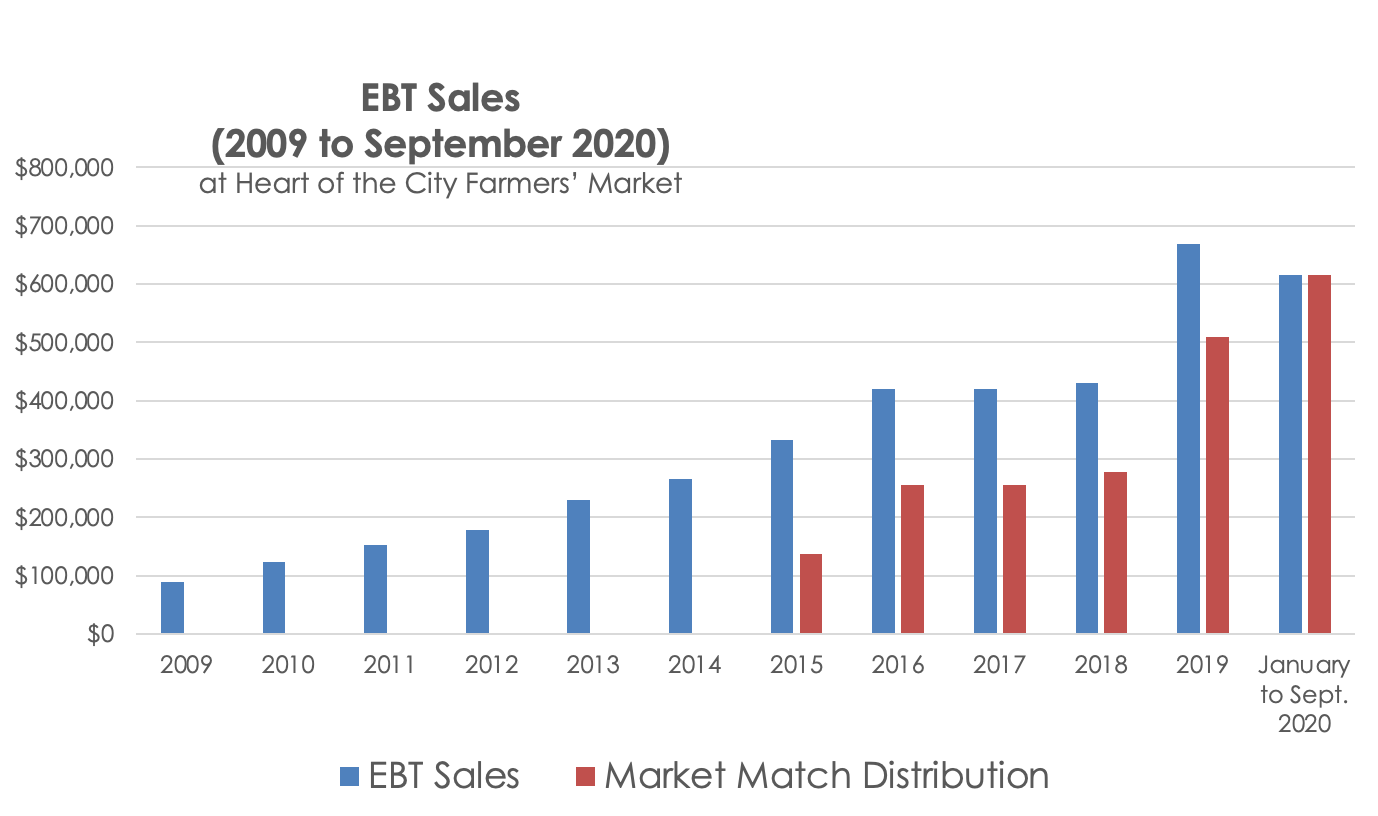

So far this year, they’ve raised $650,000, which has been passed to low-income customers to buy healthy food from vendors. In a typical year, they collect and distribute around $1 million in food assistance. It is the largest farmers market EBT program in California and one of the three largest in the nation. Much of their attention is on the Market Match program, which doubles the spending power of customers using an EBT card. Creps says, “It is critical that we continue to build the infrastructure to sustain programs like Market Match support small farmers and our neighborhood.”

The importance of the market during Covid-19 is borne out in the numbers. Participation has increased 47% in Heart of the City Farmers’ Market’s food access programs during the pandemic and they estimate that they serve more than 1,400 low-income CalFresh EBT customers each market day. Over 2,000 new participants have joined their food access programs since the start of the pandemic.

In just nine months, Heart of the City has already exceeded the amount of food relief distributed in 2019 by $115,000.

The market relies on the generosity of its community partners and customers for financial support. Those who would like to donate can find out more here.

Considering that farmers’ lives and businesses have been thrown off track, their passion for providing customers with quality produce doesn’t appear to have been scratched — if anything, just the opposite. Toward the end of our interview, a Two Dog Farm customer interrupted to ask Mark Bartle about the best way to prepare peppers she purchased. “What do you suggest I do if I want to use these all at once?”

Bartle’s attention quickly shifted away from our conversation to the question at hand: “Pan fry them, squeeze a lemon on them, have a plate of coarse salt next to them, dip them and eat them while they’re still hot, right out of the pan.”