It’s official. Last week, beloved Lucca Ravioli Company closed shop in the Mission District, breaking the hearts of customers and lovers of all things Italian in San Francisco. Since 1925, the little shop had been selling imported wines, cheeses, cold cuts, olive oils, pastas and more. But more than that, it had served as a landmark, preserving what was left of the Italian community in the Mission District.

With Lucca’s departure, we aren’t just losing out on delicious homemade marinara sauce or fresh manicotti; we’re also saying goodbye to the remnants of Italian culture and food shops in a neighborhood where they once thrived.

Back in the day, the Mission was like a little Italian suburb.

“There used to be quite a population of Italian Americans here,” said Michael Feno, the heir of Lucca, who’s been working at the family-owned business since 1966. At just 11 years old, Feno started chipping in and sweeping the floors. When his father passed away in 1987, he inherited the shop; it had been passed down through the family over the years, starting with his great-uncle Francesco, who migrated to San Francisco in 1921 and opened Lucca the next year.

Back in the day, the Mission was like a little Italian suburb.

Before the modern-day gentrification that’s resulted in the eviction of a large fraction of the Mission’s residents over the last decade, the neighborhood went through many changes as various groups inhabited it over the past centuries. Before the 18th-century Spanish colonization, the area was mainly home to indigenous tribes, but the Gold Rush brought a new wave of immigrants of German, Irish and, yes, Italian descent in the 1850s. Today, people think of the neighborhood as an area where Mexican and Central American immigrants settled—and, of course, they did and maintain a strong presence today—but that shift didn’t take place until the 1950s.

“Being Italian in San Francisco and Northern California is different from being Italian in the East. Italians did pretty well out here.”

Throughout its transitions, the neighborhood has been a place where different communities could coexist, eat each other’s food, share the same streets for funeral homes and even worship at each other’s churches––like the first Italian national parish, the original Archdiocese of San Francisco, which has celebrated being an “immigrant church.”

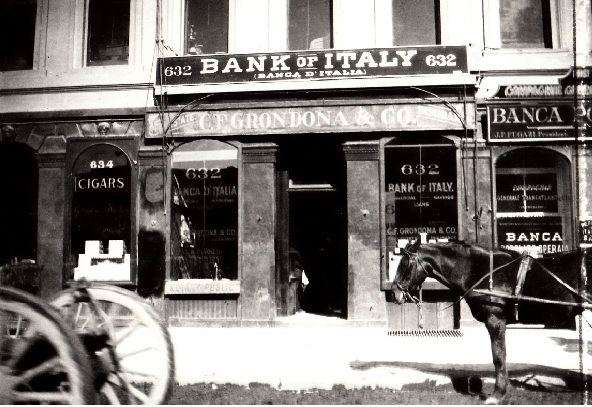

But not all Italians were part of the upper echelon that could afford booming San Francisco. The city attracted provincials from Northern Italy who mostly worked in banking. In fact, in 1907, the first Bank of America branch (formerly known as A.P. Giannini’s Banca d’Italia or Bank of Italy) opened in the Mission with the goal of “building up” the neighborhood to compete with the predominantly Italian North Beach, which claimed the “Little Italy” title.

While Northern Italian bankers grew to like to wealthy San Francisco, Sicilians and Southern Italians in American mostly worked as fishermen, who resorted to settling on the East Coast.

“Being Italian in San Francisco and Northern California is different from being Italian in the East,” said Lawrence DiStasi, board member of the western chapter of the Italian American Studies Association. “Italians did pretty well out here. They had access to banking and wide-open farmland.”

It’s no coincidence that the largest contingent of Northern Italians who came to San Francisco were Lucchese, from the Tuscan region of none other than Lucca.

For its historical significance, Lucca Ravioli was more than just a retailer.

“I’ve been coming here for over 30 years,” said customer Robert Diaz on a crowded day one week before the store closed. Born and raised in San Francisco, Diaz is now based in Oakland but still travels to the Mission just for Lucca. “It’s the way they prepare it, how they slice everything. That’s what makes a difference.”

Although soft-spoken, Feno was always seen chuckling with his customers — new and regular alike. But he wasn’t an identifiable boss. The Lucca crew shared roles. On average, his daily crew included 10 preppers, who’d go from slicing mortadella or prosciutto to ringing you up at the counter — all wearing the same triangular paper hat, a token of authentic delicatessen attire.

In the back were fridges full of turkey meatballs, veal tortellini, beef manicotti, stuffed gnocchi, fresh pesto, grated parmesan and tubs of marinara. Oh, and—of course—boxes and boxes of their darling homemade raviolis.

After World War II, the majority of the Italian community in the Mission and even North Beach began to disperse to more affluent neighborhoods in Marin County and the East Bay. While North Beach still emulates “Little Italy,” the shops that once catered to the demographic in the Mission have closed. Before it closed, Lucca had stuck out like a sore thumb. With its green, white and red awning, which embodies the Italian flag, and its hand-painted paper signs, drawn by its manager, Jim Langell, customers treasured its authentic vibe.

Walking inside the small deli of just 1,700 square feet, you were immediately greeted by a ticket dispenser and the pastry corner, featuring SanSiro panettone, traditional pizzelles and classic sprinkled-cookie assortments. Temptation always invited you in. In the back were fridges full of turkey meatballs, veal tortellini, beef manicotti, stuffed gnocchi, fresh pesto, grated parmesan and tubs of marinara. Oh, and—of course—boxes and boxes of their darling homemade raviolis.

“There’s nowhere else like it,” said Ricardo Cascio, an Italian American from San Francisco who’d been shopping at Lucca for 25 years. He complained that North Beach delis were always too touristy and expensive for him.

The ceiling — a map of Italy––paid homage to the cuisine and culture of this place, which attracted swarms of shoppers every day.

So when Lucca announced its official closing, it was undeniably a heartbreaking moment for longtime shoppers, Missionites and Bay Area residents alike. Feno couldn’t pass down the family heirloom to anyone, so he listed the property for sale. The building and its adjacent properties are listed at $8.28 million for the bundle but are also being offered separately.

“It’s not just a deli; it’s a destination,” said Elizabeth Vasile, an urban geographer and academic administrator at UC Berkeley, and former tour guide of the notoriously Italian North Beach. Vasile said that even authentic delis don’t have market value in cities anymore, especially ones like San Francisco.

But Lucca, unlike most historic delis, wasn’t in competition with local markets and supermarkets, despite them all selling Barilla and De Cecco pastas. People traveled from all across the Bay Area to pick up their 50-count raviolis and imported Italian goods at Lucca. Despite its success, Italian cuisine like Lucca’s will be hard to find anywhere else.

So what’s left of Italian culture in the Mission District? Not a lot — only a few spots have sprouted up, mostly only through revitalization. On the edge of Potrero Hill, for example, you’ll find the swanky Italian American social club Verdi Club, built in 1916, which is now a popular event space. Similar changes are happening in North Beach too. Last month, the notorious Beach Blanket Babylon, which performs in the former Italian community center Club Fugazi, announced it would shut down after 45 years too.

You can still find Dianda’s bakery, often overshadowed by its famous next-door neighbor, the tourist attraction that is La Taqueria. Known as the Italian American Pastry Company, the bakery has survived 57 years in the Mission. Another family-owned business, Dianda’s was passed down to the sons of Mr. and Mrs. Dianda, who immigrated from Lucca, Italy.

Across from Dianda’s is the last real ristorante in the Mission—La Traviata. While Lucca’s ravioli might be extinct, there’s comfort in knowing that at least a taste of unadulterated Italian cuisine remains––and as Italian-Americans would say, it’s like dining at your Nona’s house.