It’s a bad idea to fall for a barista. They only ever bring you just what it was you wanted.

This one in particular was tall and bookish and bought his shirts at Macy’s. A dweeb, you might say. But perfect in all the ways boys are when you admire them. I tried for the window seat, where I stared at him while he was at the counter, then averted my gaze to the street when he noticed me staring.

The cycle of lovelorn hangouts goes like this: you go to a place and like it. So you go back and back again. The staff notices you, makes your usual as you step in the door and then … well, it gets complicated.

When you’re a regular, it’s not hard to feel like you’re the object of especial adoration. You start to feel cared for, and you get to caring about the place and about them, thinking about the wait staff in your off time and wondering what drinks they’re mixing when you’re not there.

At the time I was living in Seattle and frequenting a tea place in Ballard some distance away from the Wallingford basement I shared for $370 a month with a bio-statistician/yogi and her cats. I went most days to the tea shop, from mid-morning to early afternoon, where I fell for the barista.

Why is it that nearly all gay men seem to have had at some point in their lives a professional friendship with an attractive older woman who resembles Vanessa Redgrave?

My usual hours and preferred seat coincided with those of an older woman who had been working on a novel. She looked like an elderly British actress, with her tweed jackets and long gray hair pulled back in a no-nonsense ponytail or bun, and brought to writing the same dedication she brought to her personal accounting practice. (As a side note, why is it that nearly all gay men seem to have had at some point in their lives a professional friendship with an attractive older woman who resembles Vanessa Redgrave?)

We usually sat together, a pair of familiar strangers, to drink tea, flip through books and only occasionally gossip about whatever we were reading.

One day, when I was neglecting my book and staring into space, she noticed and asked me about it.

“Why do you come here?” she asked.

“Red shirt,” I said, with the slightest of gestures, not wanting to give myself away.

“Which one?”

“Tall, angular, glasses, perhaps a quarter Asian.”

“Oh yes,” she said, approvingly. “He is handsome.”

“I know,” I said, feeling incapable. In the time that I had become a regular, there was no hint that the interest was mutual. I had also received a job offer that week in San Francisco and would be relocating during the second week of January. My time in Seattle suddenly had an expiration date.

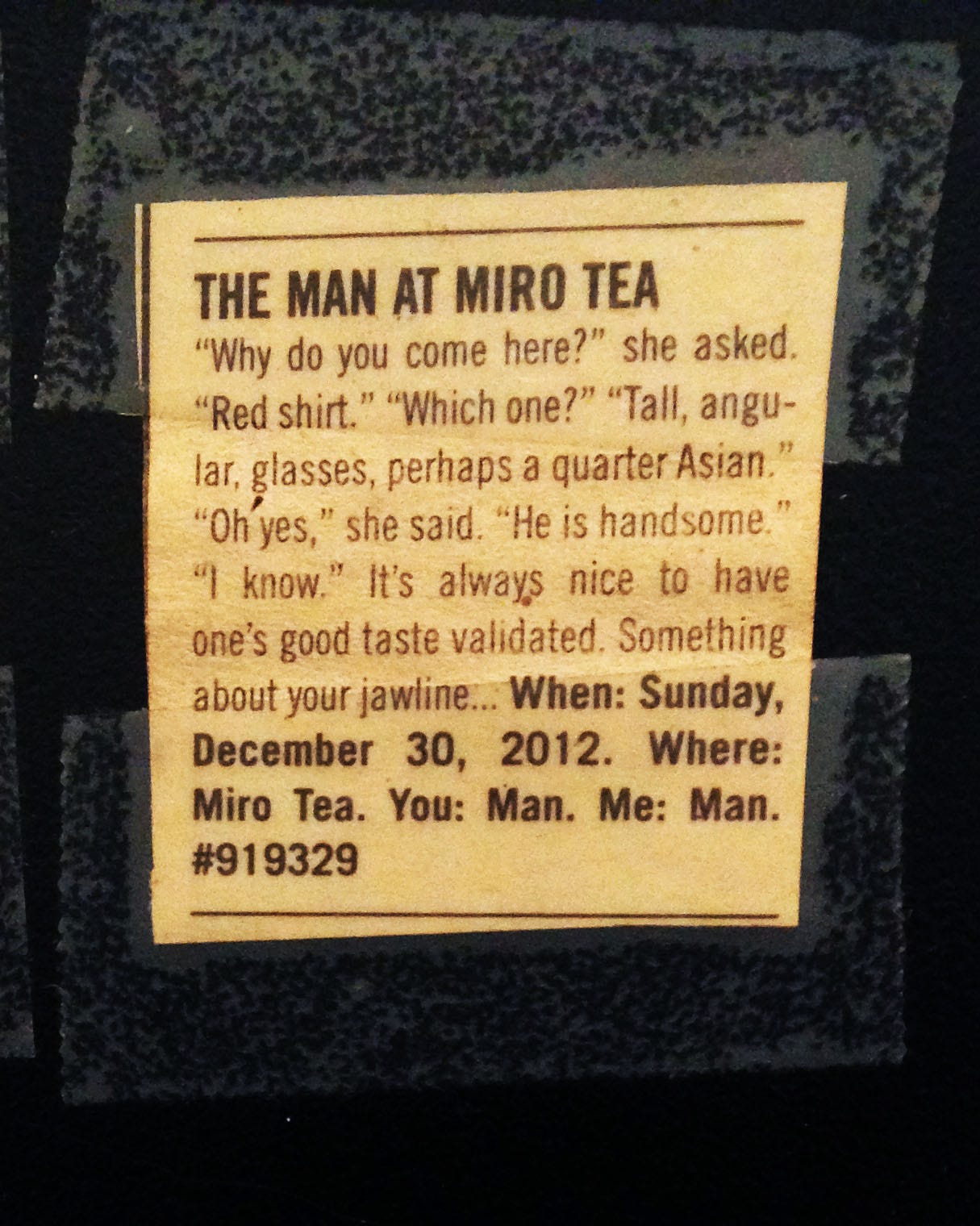

Just before I left, before I boxed the last of my things and shipped them off to Oakland, before I bought a new pair of shoes and a tie, before 2013 and all its individual disappointments had any chance to arrive, I wrote a piece to him — and about him, and about her, and about the tea place. Too little for an article. Not enough for a story. Just enough for Lovelab, the missed-connections section of the Seattle Stranger.

Four years later, when I was back in Seattle, another friend (not the writer, nor the yogi) suggested the tea shop as a meeting point.

We went at about 10:00. We sat at the window. I faced the counter. Even with all this, I still didn’t remember, until we went to pay, and I noticed by the register a yellowed newspaper clipping the size of a postage stamp, taped to the side of the display case, dated December 30, 2012.

Not every wordsmith, but most, has some target demographic in mind when they write. In my case, twentysomething tea-shop workers with dashing jawlines and attractive taste in eyewear.

My first piece of published work — ever — had been made real on paper, and I had forgotten all about it. And to be honest, I had forgotten him as well. And Vanessa Redgrave. And even the tea shop.

He wasn’t there. Four years is a long time to be a barista. But it was the best compliment I could have received. The words had found their reader and left him affected. My intended audience of one noticed that I had noticed. A 100% success rate. Bull’s-eye. So it was perhaps not only the first piece I had ever gotten published, but in its way it was also the most successful.

And yet neither of us ever knew the other’s name.