the shop is bustling and a cadre of vintage Hondas are lined up in front. Sometimes my 1975 CB360 is among them. Today is Sunday, though, and Charlie O’Hanlon, the namesake of Charlie’s Place, meets me on his day off to talk about how he accidentally became the local authority on vintage Hondas, as well as a sculptor of motorcycle parts.

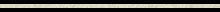

The shop is closed and bikes fill the small garage. They are lined up side by side, end to end, a testament to the constant stream of work local riders provide. San Francisco’s vintage-loving culture has grown to encompass motorcycles, especially old Hondas, which seamlessly marry riders’ desires to avoid abysmal public transportation while decreasing their ecological footprint in coveted style.

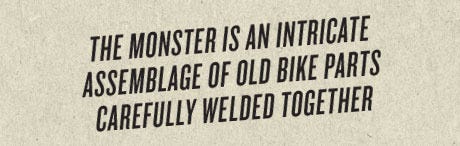

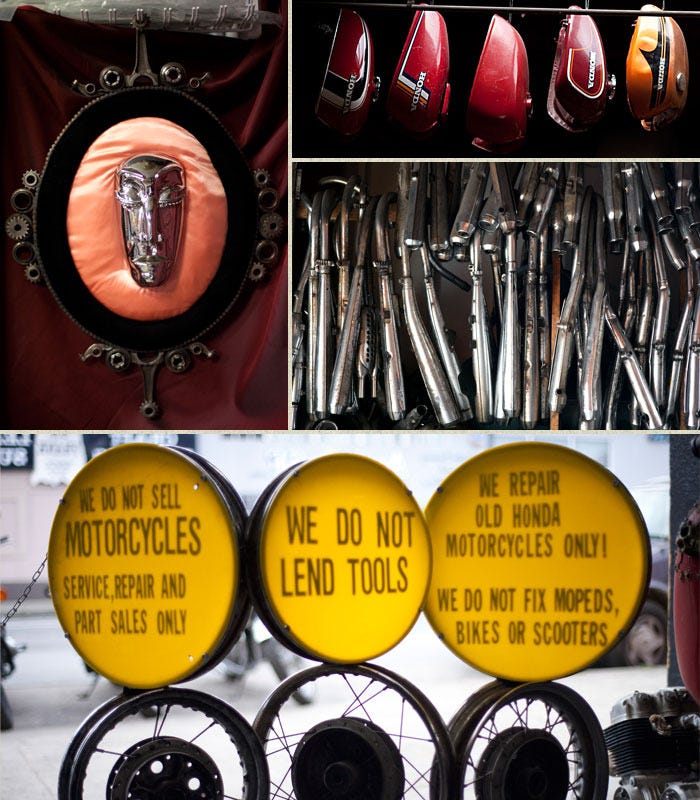

As I come up to the metal Godzilla that guards the entrance to the shop, I see the space with new eyes. The monster is an intricate assemblage of old bike parts carefully welded together. Past him, old gas tanks line the balcony railing in a rainbow of rust-tinged metallic hues. Amidst the chaos and motor oil grease, there is an order here that reflects the personality of an owner who is an accomplished mechanic and artist.

Charlie has serviced countless vintage Hondas since opening his shop in 1998, and has witnessed the evolution of bike culture in one of the best places to be a motorcyclist. A New Yorker by birth, he didn’t start driving until he moved to San Francisco. He came here for art school, but had a hard time buying into the idea of being taught how to make art. So he dropped out, and then needed transportation to get to the various jobs he picked up, so be bought a bike.

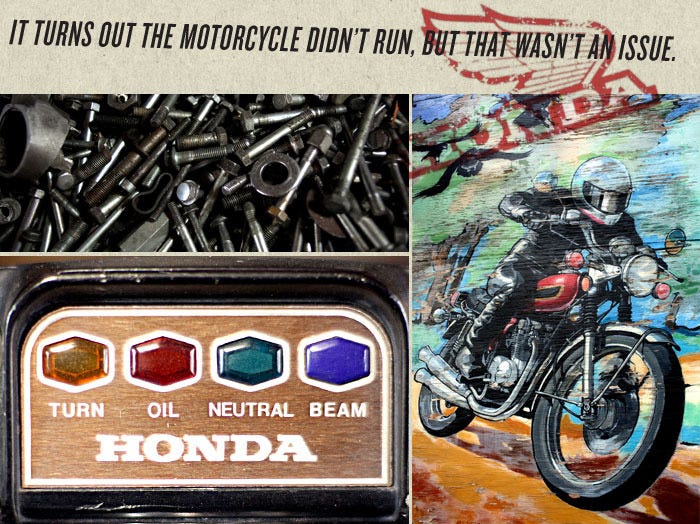

It turns out the motorcycle didn’t run, but that wasn’t an issue. “I can fix almost anything with my hands, so that’s what I did,” Charlie explains, as if teaching oneself to be a mechanic is an everyday feat. He also figured out how to ride, because the Motorcycle Safety Foundation, which teaches DMV-approved riding courses, didn’t exist yet. “The way you learned to ride was to find a friend who knew how to ride,” he adds.

As Charlie started fixing up more cheap bikes, he found he’d unwittingly started a small business and formed an identity in this city.

The decision to specialize in old Hondas is an odd one, though. Unlike Ducati, Moto Guzzi, or BMW riders, Honda riders are generally looking for reliability and affordability. Far from the stereotype of the motorcycle enthusiast as an adrenaline junkie on a sleek sports bike or a freewheeling hippie of the Easy Rider variety, Honda riders are everything from practical commuters to vetted road-trippers. I ride a 360 twin, a small bike by most standards, but larger than most two-cylinder engines. Charlie has long tried to convince me to abandon my ride in exchange for the more reliable, more commonly available 400-Four.

He started out working on 350 twin Hondas because nobody would service them. After carving out a niche for fixing them, he eventually began to see the beauty of the simple Japanese bikes. Someone brought him a Superhawk and asked, “Can you fix this? Nobody else will.” He was blown away by how beautiful and well designed the bike was. After he mastered that one, he was introduced to a friend who had a Honda Dream, which he figured out how to fix as well. Now the man who started out on a Kawasaki focuses solely on Hondas, and rides a number of them himself.

As much as he loves working on old Hondas, Charlie doesn’t limit himself to repairs. When I ask him what he’s riding these days, his face lights up at the opportunity to talk about a new electronic ignition system he’s testing. And when he’s not building bikes or inventing new parts, he’s using old parts to create things like the Godzilla sculpture, or a collection of guitars made out of recycled gas tanks and wheels. He plays one of his homemade guitars in his band, The Feral Cats.

The ultimate goal of Charlie’s Place, though, is to keep old Hondas running and help expand San Francisco’s amazing motorcycle culture. Charlie takes great pride in this state. He has zigzagged across both coasts and road-tripped through the middle, but says California takes the cake.

For beginners, he says the most important thing to consider before riding is that you have to be able to put both feet firmly on the ground. Charlie is constantly surprised by the number of new riders who aren’t on the right-sized bikes, thereby risking having a bad experience that could turn them off for good to the wonderful world of motorcycles.

In the end, he says, riding is like anything else you want to do — it depends on “how determined you are to persevere against anything that stands in your way.” He smiles as he says this, getting up to play me some of The Feral Cats’ latest music.

Charlie’s found his place, and I’m glad my bike and I have found ours, too.

Getting your motorcycle permit is as easy as downloading the DMV’s handbook and passing the written test. There is a driving test at the DMV, but the Motorcycle Safety Foundation offers a class that not only teaches new riders, but also certifies them to get a license without taking the DMV test.

Local shops like The Bikeyard rescue old motorcycles with more personality than you can shake a stick at.

Find an old Honda that suits you and take it to Charlie’s Place for a good looking over.