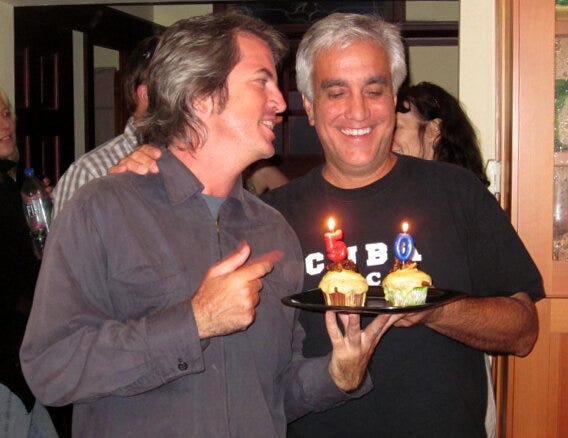

Six days after my great friend Pedro Gomez of ESPN died of sudden cardiac arrest on February 7, 2021, I stood at home plate in a baseball stadium in Scottsdale, Arizona, and gave a speech comparing Pedro to the ideal friend evoked by John Cusack in a 1980s movie called The Sure Thing.

“Nick’s your buddy,” I quoted. “Nick’s the kind of guy you can trust, drink a beer with.”

“That’s Pedro, our buddy,” I continued, looking out at the Covid-tested, socially distanced, invitation-only crowd, “and it’s a little surreal to see this outpouring of love and respect for Pedro, ripples emanating out from a point in the middle, our Pedro, occasionally a goofball, interrupting himself with fits of laughter in the middle of a story he’s already told you eighty-three times, but also a truly beautiful soul, a man of courage and commitment so deep, it reached people who could not be reached.”

Pedro’s death inspired an outpouring on social media — “RIP Pedro” was trending on Twitter — and emotional tributes on ESPN and elsewhere by, among others, Rachel Nichols and Peter Gammons. The New York Times ran an obit, calling Pedro “a Pillar of Baseball Coverage for ESPN.”

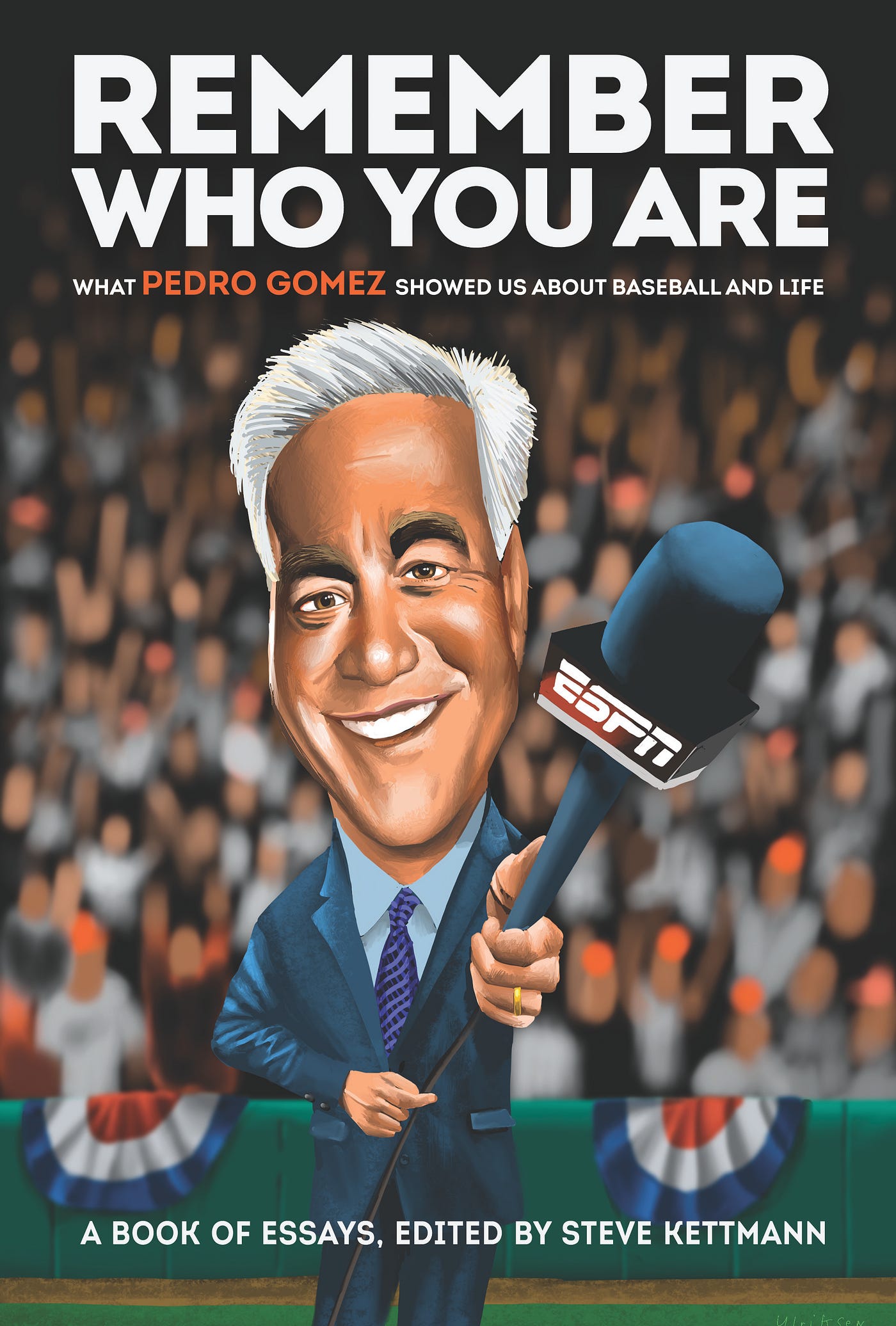

Back home in California after the drive to Arizona for that memorial, along with my wife, Sarah, and two young daughters, Coco and Anaïs, I threw myself into three months of intense work assigning and editing a book of personal essays: Remember Who You Are: What Pedro Gomez Showed Us About Baseball and Life, which we will publish in July through our Wellstone Books imprint with national distribution through PGW and national media attention.

(The book eventually ended up a doorstop at 440 pages, room enough for sixty-two essays and 185 black-and-white photographs.)

My friends kept reaching out to tell me not to push myself quite so hard, reminding me I’d lost a close friend and had to take care of myself. I thanked them and said I understood but actually I had no idea what they were talking about: My friendship with Pedro was all about conviction, all about giving a shit and acting on what you believe.

There was no time to waste. I needed other people who also cared about Pedro to tap into the strong feeling he inspired and to share that with readers in a way I knew would be unusual and powerful. If I could not rise to that challenge, what was I?

(Brad Mangin, a great sports photographer Pedro had been talking to me about for years, took to the project in the same spirit as I did, appointing himself picture editor and working long hours to fill the book with amazing shots.)

I reached out to one of Pedro’s and my favorite writers, Tim Keown, a former San Francisco Chronicle columnist turned ESPN writer. In writing as in life, Pedro and I loved to talk about people who went for it and put it all out there, like Roberto Clemente in the corner, wheeling around to unleash a laser throw to third base. Tim was a Clemente-in-the-corner guy all the way, and Pedro and I never tired of quoting one line of his about showing up pregame at Yankee Stadium one October with the sound of the 4 train “rattling overhead like a diseased lung.”

“Packaging, over time, is indistinguishable from the product,” Tim wrote in the searing essay he emailed to me after two or three times insisting he didn’t have much eloquent to say. “Along the way, as we’ve macheted our way through the thicket of superficiality and false humility, the search for authenticity has become a subversive act. To seek authenticity is to risk being branded a cynic.”

As with so many of the essays sent to me those weeks, I was frozen in my chair as I read, leveled by the power of the words.

“Pedro sought authenticity the way a wildfire burns toward dry fuel,” Tim said, adding “he was a one-man rebellion, chiseling through the hagiography to get to whatever story lay buried inside.”

Tim continued: “There were enough stenographers out there; Pedro sought to understand, in both of his languages. If he felt a ballplayer or a manager was spinning him, Pedro would take a step back and plead with those arms again. ‘Come on!’ he’d say, refusing to hear another word. It was an authentic appeal to authenticity, and, suitably disarmed, the ballplayer or manager would laugh and proceed to tell Pedro what he was there to discover. He was a man who lived out loud in a world that was inexorably retreating into its own self-reflection.”

The book also contains moving essays from major figures like AJ Hinch and Ron Washington, who both had the experience of going from center stage in the baseball world, managing in the World Series, to the agony of scandal — in Hinch’s case, the fallout from the Astros’ sign-stealing, in Wash’s, a years-old revelation about cocaine. Both describe talking to Pedro in those darkest hours — and having him be there for them, a reporter doing a job, yes, but also a friend offering support and understanding. Both describe Pedro giving them some of the best advice of their lives, which boiled down to this: Dare to keep being authentic, in the middle of trouble, and the truth will set you free.

Pedro’s singular gift for bringing out the best in people he loved — his family and each and every member of his impossibly vast network of friends—is something many of us find very hard to go on without. To talk to Pedro in a moment of joy was to have that joy amplified and extended.

Pedro’s and my close friend T.J. Quinn, an investigative reporter for ESPN, also contributed an essay, “How Do You Want to Be Remembered?” T.J. and I keep sharing examples of those times, nearly every day, where it seems impossible that we can’t call or text Pedro.

“Mikey Quinn 3-for-4 in Teaneck’s crucial win over powerhouse Pascack Valley today,” T.J. texted me in mid-May. “He’s up to either .392 or .435, depending on how they scored one play. And it hurt me physically not to share it with Pedro.”

It hurt me physically to read that, as it hurt me physically earlier that day when something amazing had happened, and I had to remind myself that no, I could not just tap the phone and hear Pedro’s voice instantly rising with enthusiasm to hear what I had to tell. A friend so solid that when he’s gone you feel part of yourself is missing, like a lost limb.

One day later, my six-year-old, Coco, called out from the garden after unwrapping a book that has just been delivered to our door.

“Dusty Baker!” she cried out, happily.

I walked over to see her holding up a hardcover of Len Koppett’s classic The Man in the Dugout: Baseball’s Top Managers and How They Got That Way. Sure enough, there on the cover, over on the left, was Dusty in his days as Giants’ manager smiling that cool-dude smile, and I loved that Coco recognized him. Again, it wasn’t so much that I wanted to call Pedro or send him a picture of Coco holding up the book showing Dusty, it was that I was already happy knowing that I would, aware at some foundational level of how these moments of connection had sustained and elevated me for decades, as essential and basic as breathing. It was, once again, jarring to reimagine myself into a world in which no more such calls would take place.

I’ve been thinking about “Nick,” your buddy, and dude friendship. I’ve been thinking about mourning and hurting, and how much time can elapse with it all feeling so raw, so fresh like a concussion just delivered by a blitzing linebacker on a frozen football field. (Yes, I was there in Buffalo in January 1994 covering the AFC Championship for the S.F. Chronicle when Joe Montana, by then quarterbacking the Kansas City Chiefs, banged his head on the frozen ground and had to leave the game.)

My wife has been amazing, she loved Pedro too, she finds it astonishing to imagine a world without his warm presence, and yet, I can’t talk to her every single day about the pain feeling fresh or the sense of loss feeling infinite. I have to bottle some of it up, play tough guy, go out and dig huge piles of dirt in the garden and almost throw out my back, and at least I’m doing something, physical labor, sweaty and dirty, dude stuff.

Does it help? A little. Did editing all those essays? Yes and no. It added to both the pain and the catharsis.

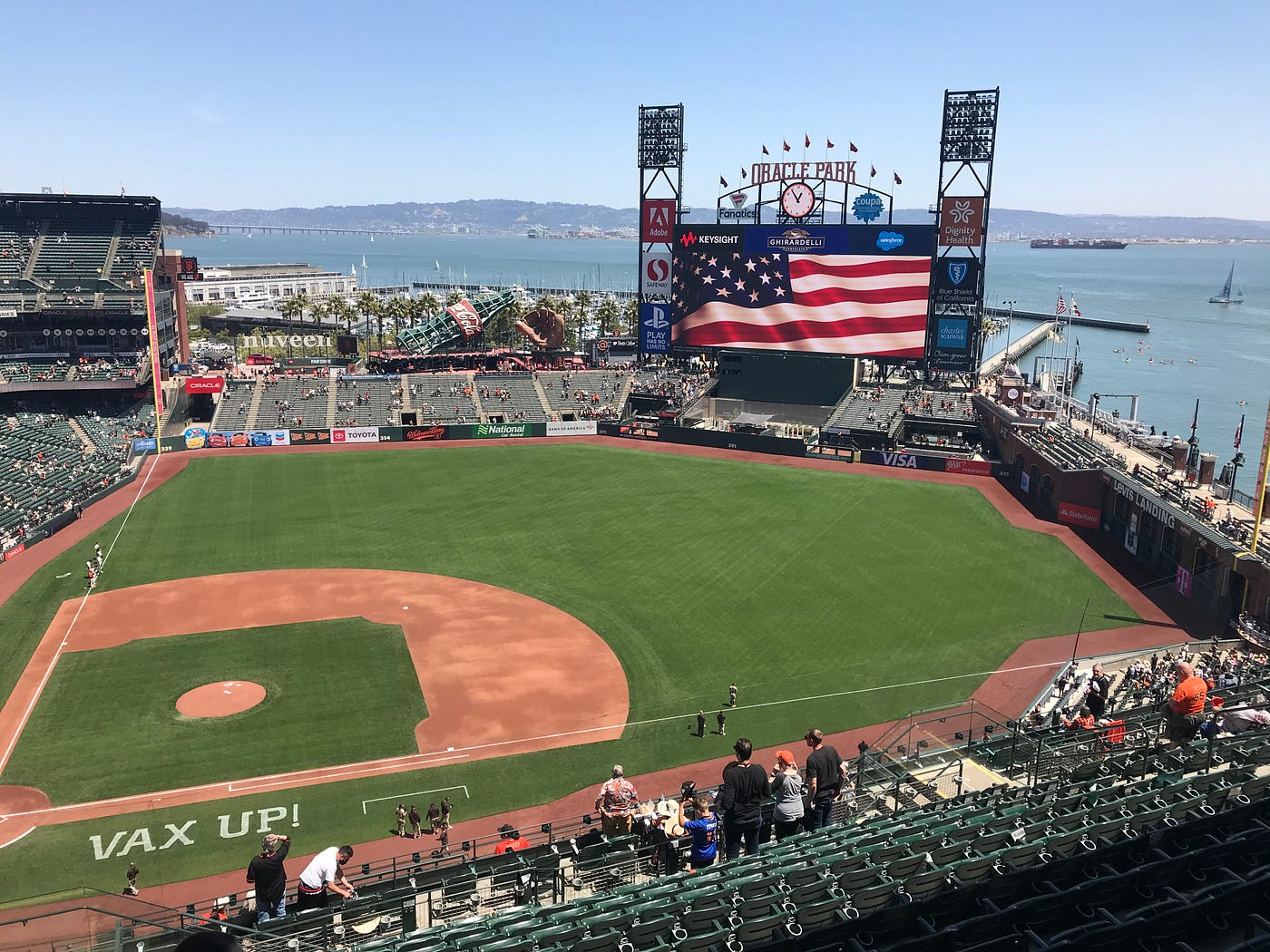

I drove over to San Jose with Sarah and the girls to celebrate my brother Dave’s birthday. (“Brother Dave!” Pedro called him, singing it out.) Two seasons earlier, my last time watching baseball in person, Dave and I had gone up to San Francisco to see the Giants play. This was our first family gathering since pre-Covid, and I presented Dave with tickets to the next Saturday’s home Giants game. We had a beautiful day together, almost like being kids together, bunk bed mates laughing and playing.

Except: As much as I enjoyed the exquisite day, the view out over the bay from our upper-deck seats, and as much as I enjoyed hearing brother Dave talk about the intricacies of his work as golf coach at a San Jose high school, it took me a while to admit that something for me was a little off. I tried to ignore it. But when I went to get us a couple of bratwursts, and had a minute alone, what I’d been feeling all along kicked in with more force. I felt what amounted to a dull ache, a feeling like hoping your cracked ribs have healed, only to find them jarred once again, a feeling of any visit to the Giants’ home stadium demanding multiple calls and texts and voicemails to and from Pedro, whose presence in that stadium is very strong.

I’m left with a sense that guys need a lot of help in navigating this kind of grief, and maybe the essays in Remember Who You Are can help them a little. Maybe stories of a guy always looking for a way to make his friends’ days better might inspire people to try to be friends the way Pedro was a friend, generous to a fault, but always himself. Or as Keith Olbermann puts it in the final essay of the book, “All Friends Are Best Friends,” which you can read in full here.

Pedro and I were like bench coaches to each other, there to think through a potential problem or intriguing but fraught situation, there to look ahead and anticipate. He often called me “Coach,” for a lot of years, like, “What do you think, Coach?” and that went both ways.

I’ve had moments, since Pedro’s death, when I knew I was failing in my ongoing attempt to try, in his absence, to be a little more like him. Pedro could get his back up, he called it going Cuban, but he was also very good at looking past the petty or the petulant to stay focused on what actually matters. Emulating that particular quality remains for me a work in progress.

It’s a little thrilling and scary, trying to be more like Pedro, which is of course an impossibility. They only made the one.

Then again, the impossibility of anyone filling his shoes is freeing in a way. Or that at least was what I kept in mind when I talked recently with Pedro’s son Rio, who I’ve known since he was a baby. The first diaper I ever changed, in fact, was Rio’s, one spring-training night when I filled in as babysitter so Pedro and his wife, Sandi, could have a date night.

Now Rio is a left-hander pitching in the Red Sox organization. He has an essay in Remember talking about how his dad was his biggest fan, and how every time Rio pitched, he’d always talk with his dad soon afterward. “We talked after every outing,” Rio writes in an essay that some readers have told me is their favorite in the collection. “All of college, all of summer-ball, all of pro-ball, any time I pitched, the first thing I’d do afterward was find a way to talk to my dad. The second I got in the car, the second I just had a moment away, I would call him. Obviously, he was following the games, watching if he could or listening on the radio, or finding play-by-play on the internet. He would know what happened, but we’d go through it pitch by pitch and play by play and break it all down. We’d talk about it all whether it was a good outing or a bad outing. It was basically: How can I illustrate a picture of what was going through my mind at every point during the game? I’d been talking baseball with my dad my whole life so nothing felt more natural.”

Rio’s first appearance of the 2021 season had gone pretty well, but he’d made a mistake pitch his second time out: leaving a fastball out over the plate, where a top Mets prospect crushed it for a no-doubt-about-it homer. Talking the sequence through with Rio, the decision-making that went into it, I knew that for him it was nothing like talking to his dad, and yet, Pedro had briefed me on so many Rio outings in such detail, it felt good just to be talking to Rio about his thought process on the mound. I told him I was sure he’d bounce back, and I am. Maybe not his next outing, maybe not even the one after that, but he’ll get his groove back, I know he will, too many of us are there with him, caring more than we maybe should about the peripatations of a small horsehide-covered ball spinning in the night.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.