In his play of the same name, playwright John Guare popularized the concept of six degrees of separation — that everyone on average is six, or fewer, social connections away from each other. From the moment I first met Alessandro Baccari Jr., I discovered we shared more than a few personal connections and a love for our Italian heritage.

Spanning nearly 93 years, heart-driven by spiritual purpose, unbounded compassion, and love of God and humanity, on April 30 Baccari completed his passeggiata through life.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week

Baccari was renowned for being a walking oral history of North Beach, where he was born and raised by northern Italian immigrants Alessandro Sr. and Aida, who once lived in a flat above Mario’s Bohemian Cigar Store Café. His friend, San Francisco Chronicle columnist, Sam Whiting, called him “an unstoppable, one-man North Beach booster club, chamber of commerce and historical society.” A dedicated historian of San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf and all things Italian American, he was also famous for his colorful stories, often told while giving guided tours on his walks — passeggiatas — through his beloved Italian neighborhood.

I first met Baccari for lunch in the summer of 2017. Over the next four years, it was the first of many meetings at the North Beach Restaurant, a block from Washington Square, and Saints Peter and Paul’s church where we both attended grammar school, a generation apart, nurtured by our Sicilian-Italian community. As he sat before me in sartorial Italian elegance, I decided to forego my formal interview as our conversation soon went to a panoply of personal stories — mine as well as his.

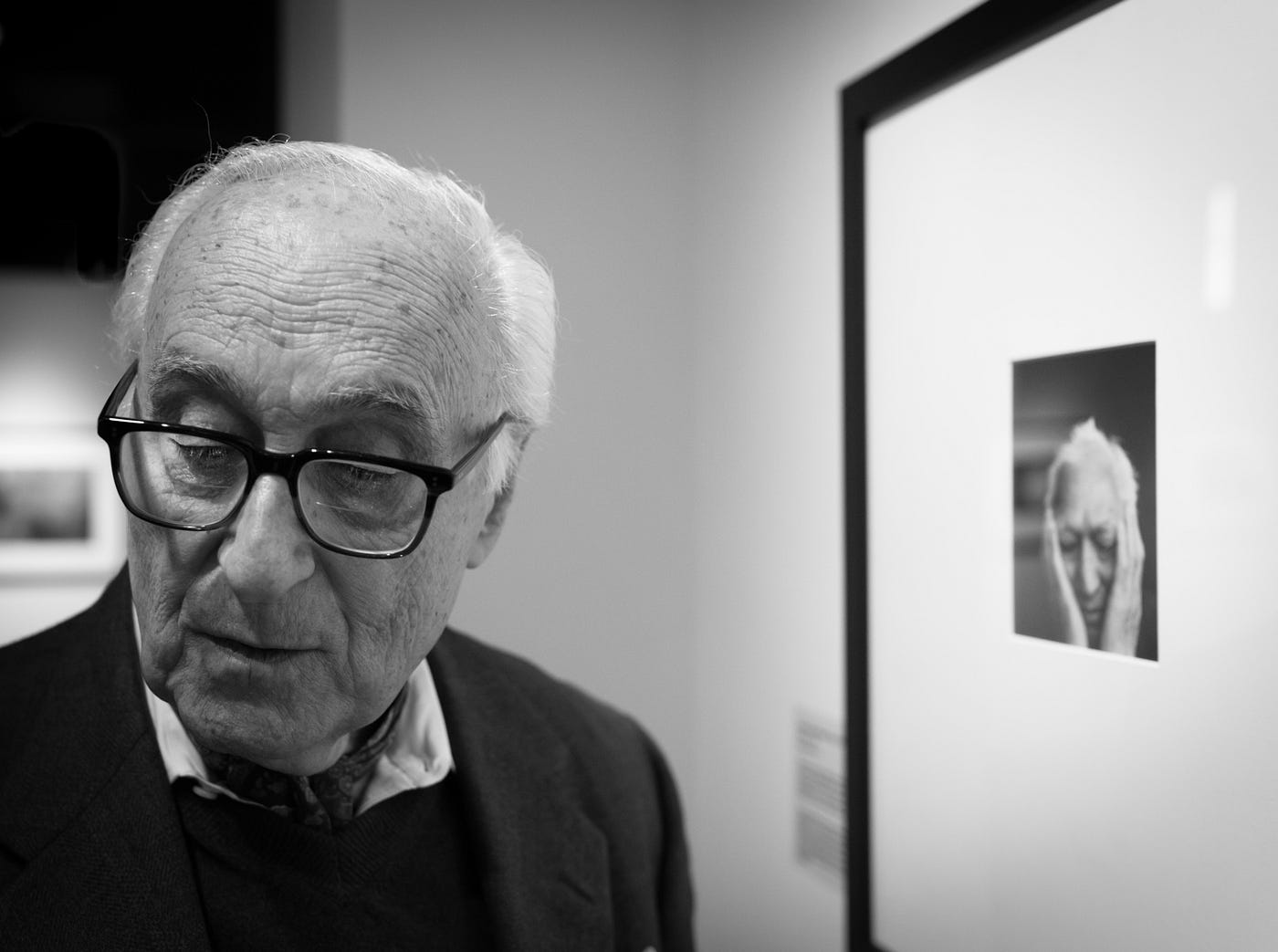

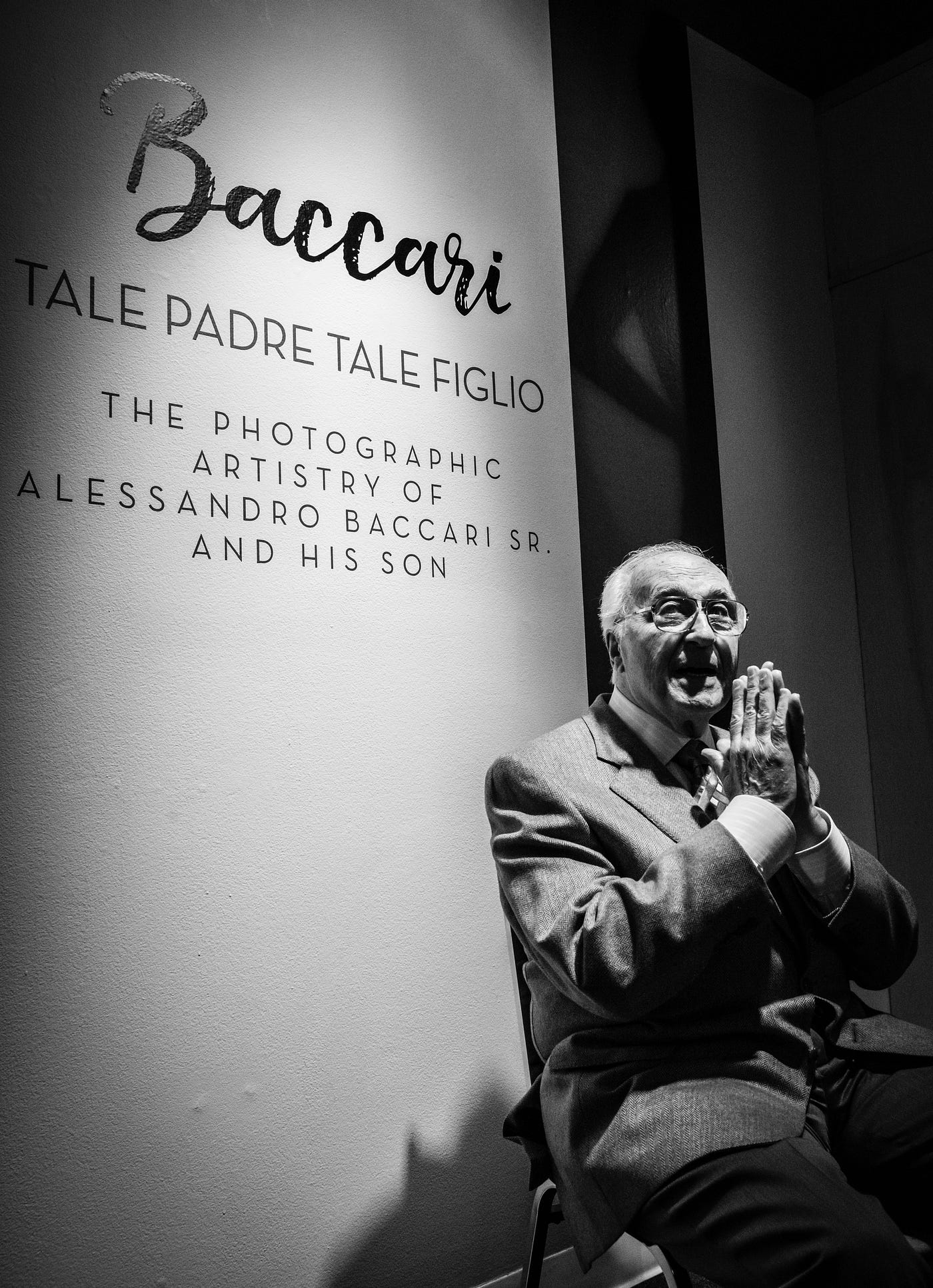

An articulate man who speaks as much with his hands as with his warm eyes and gentle face, Baccari appears to be giving Catholic mass, gesticulating as if to give the benediction. With wise eyes beaming large through his thick glasses, his animated voice and light-hearted laughter reminded me of the 1930s comedic actor, Ed Winn, known for his Perfect Fool character. But Baccari is no fool, nor does he suffer them lightly. I felt I had met a holy man, wise as the Dalai Lama, with the presence and spirit of the pope. Like his father, Alessandro Baccari Sr., he had a rich life encompassing many lives that touched me and so many others because he embraced and celebrated humanity.

A major theme of our conversations was the central importance of family and how North Beach was once a thriving community of Italian families that cherished its residents.

While Pavarotti sings Nessun Dorma over the sound system, a Chinese waiter delivers our orders: Baccari’s favorite soup — farinata, a chicken broth of cannellini beans, Tuscan kale, and polenta, drizzled with olive oil, seasoned with Parmesan cheese. Our main course is local fish. “Look at that — beautiful petrale sole!” he gushes.

“I’ve heard people often roll their eyes at your storytelling,” I said, sipping my soup, tongue-in-cheek.

Baccari throws back his head and laughs. “Oh, yes — stories. I’ve got a-million-of-um!” he says in what could be a San Francisco accent, his words running together. “Once I hear something, I’ll always remember it.”

Recognizing a regular patron, the Italian maître d’ comes to our table to greet us. “Senore Baccari, come va?”

“Sempre avanti!”

“Always forward!” was Baccari’s living mantra. And what an inspirational life, modeled after the Italian Renaissance, he lived. Once an award-winning fencer for the Olympic Club, trained in boxing as well as ballet, he was ambidextrous and could touché or sucker punch you either way. Baccari attended Saints Peter and Paul’s grammar school and is a graduate of Sacred Heart High School. With degrees in political science from Santa Clara University and UC Berkeley, he could outmatch speech rivals with a sharp riposte as well as a quick repartee.

He was a lucky boxer. No broken nose, no head injuries. “God, I did a lot of fighting. I was afraid of my maternal grandmother, Amelia, who lived in the Marina. If I ran away from a fight, she’d beat the hell out of me. She was a demon.”

On Saturdays, his grandmother would take him to ballet lessons and then to Newman’s Gym (where George Foreman trained) in the Tenderloin to learn how to box. “I remember coming home from school. Richie Napolitano jokingly slaps my face, and I turned the other cheek. My grandmother, watching from her flat, opens her window and says, ‘What’ta you do’ing?!’”

“I’m doing what mommy told me to do. Do like Jesu’ — turn the other cheek.”

“My grandmother says, ‘If I pull’a your pants down you got’ta two more cheeks and I’m gon’na beat the hell out of ‘em! You go get’em and don’t come home till-a-you beat’em up!’

“So, I chase him down to his father’s café, and his father sees me beating him up. His father starts hitting me. My grandmother comes down with a broom and she whacks him. ‘Mr. Napolitano, if you ever hit’ta my grandson again my husband’s coming after you!’ Nobody wanted to fight my grandma.”

Baccari was close friends with the older Joe DiMaggio, a second-generation Italian who also grew up in North Beach. He was an altar boy in DiMaggio’s first wedding to actress Dorothy Arnold at Saints Peter and Paul’s church, built by Baccari’s great, great uncle, Father Raffaele M. Piperni, who brought the Salesians of Don Bosco religious order to America. (Its history is chronicled in Baccari’s book, “Saints Peter & Paul’s Church — Chronicles of the Italian Cathedral of the West, 1884–1984.”)

“What a crowd!” Baccari said. “Some 30,000 people in front of Saints Peter and Paul’s church. Contrary to popular lore, DiMaggio’s second wedding to Marilyn Monroe was not here. No, I arranged that for him at San Francisco City Hall.”

“Creativity fosters longevity” is another mantra of Baccari, who managed to compress more than one life into his 92 years. In addition to being a Fulbright award-winning photographer, poet, painter, and author of three books — and a coloring book on North Beach more popular with adults, he was a city planner, speechwriter, research economist, historian, museum curator, lecturer, and an associate dean of business at San Francisco State University. During his early career, he was a radio broadcaster, filmmaker, and Peabody-award-winning TV producer working with Mike Wallace as host of the P. M. West-P.M. East show which originated from San Francisco and New York simultaneously.

With his Italian-born wife Catherine (Piccirillo), who died in 2012, he co-founded Alessandro Baccari & Assoc. in 1963, a public affairs firm that publicized entertainers and supported several city planning projects. Baccari served as a consultant to eight San Francisco mayors — including Mayor Joseph Alioto who was his close friend and mentor. His clients included the hungry i night club and the Playboy Club, and he helped to introduce Lenny Bruce, Bill Cosby, Mort Sahl, The Gateway Singers, The Kingston Trio, and Barbara Streisand, among others. “I did all the ads for the hungry i,” he said. “Enrico Banducci still owes me $12,000!”

Fisherman’s Wharf was one of Baccari’s key accounts; but more than just work, the wharf, and its people were the love of his life. His book, “San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf” (2006), remains one of the best historical accounts on the subject. As a founding member of the Wharf’s Historical Society, he was pivotal in establishing the non-denominational Fishermen’s and Seamen’s Memorial Chapel in 1981, which honors the names of those who perished at sea.

Across from Pier 45, the chapel is the site of The Annual Blessing of the Fishing Fleet and Madonna Del Lume (“The Mother of Light”) Festival, a Sicilian tradition originating in Porticello, Sicily. At the age of seven, Baccari spoke in English and Italian at the first Madonna Del Lume festival in 1935. Not long thereafter, he would serve as its master of ceremonies for most of his life.

Baccari once wanted to be a Broadway song and dance man. He knew Frank Sinatra who’s act he once followed at the Cal Neva Lodge & Resort in Lake Tahoe. “Sinatra just finished his act. I would put my head between the curtains, get a spotlight, and tell the audience, ‘You’ve heard all these great acts. Now, you ain’t heard noth’n yet!’ And the curtain opens: ‘Toot, toot, tootsie goodbye’ — my cane tapping. I could tap, run against the wall, and flip over like Donald O’Connor. I can’t do that now, I’d kill myself!”

Over one of our lunches, I learned Baccari knew my baptismal godfather, Joe Conforte, the world-reputed “King of Prostitution,” founder of Nevada’s most notorious house of ill repute — the Mustang Ranch. While working as a broadcaster for local Westinghouse KPIX TV, he did a broadcast from Virginia City, profiling Conforte and what it was like running a brothel.

Conforte offered to fly Baccari to the brothel on his private plane to sample his special services. “I don’t want you to worry. Every girl is certified with a stamp on their ass. I’ll fly you back,” Baccari recounted, exaggerating a gangster accent. He politely declined.

Like his son, Alessandro Baccari Sr. was also a Renaissance man. An Italian immigrant from Tuscany who grew up in Naples, he was a highly accomplished painter, playwright, musician, and photographer who had studios at Powell and Sutter Sts. and above Fugazi Hall on Green St. He knew Paul Robeson — the black-listed actor, deep bass singer and Civil Rights activist; Guglielmo Marconi; Edward Weston; Ansel Adams; Eugene O’Neil; Benny Bufano; and Harry Bridges — San Francisco’s famous leftist labor leader who led the four-day longshoremen strike that resulted in “Bloody Thursday” in 1936.

“Marconi loved him so much, he made him his official photographer,” Baccari said. “Dad was the photographer for all these great ballet dancers, opera singers, and play-actors.”

Baccari’s father introduced him to Luciano Pavarotti and Benny Buffano with whom Baccari Jr. became good friends. “If she walked, talked or crawled, Pavarotti would try to screw her,” he said. “For 30 years I spent Christmas with Bufano — he was helluv’an artist.”

It’s August 2017. Baccari stands at the lectern before a small crowd of admirers at the Museo Italo Americano, at San Francisco’s Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture. He’s here to introduce Tale Padre Tale Figlio (“Like Father, Like Son”), a joint photo exhibit illustrating the unique insights into composition and design he and his father shared.

Baccari explains how his father would ask his friends William Saroyan, Eugene O’Neill, Paul Robeson, and Edward Weston — “Would you be the father of my son for a day?” In this way numerous surrogate fathers helped train him about their professions, and informed “The Fathers My Father Gave Me,” the last book Baccari Jr. was writing before his death.

“My father sent me on the train to Monterey to meet Edward Weston — I was 12 years old,” Baccari recalls. “Weston said, ‘Your dad wants me to talk to you about life, and we’ll talk about life…but first we’re going to go photograph the beach.’

“So, I said, I’ll go get my camera. ‘No camera. Your father wants me to explain how to photograph with your eyes.’

“So, we go to a Carmel beach. We’re not there one minute. He says, ‘Close your eyes!’ I close my eyes. Jesus, I got scared.

“‘What do you see?’ I see the water, rocks. ‘You’ve seen nothing!’ We spent days just shooting with my eyes. To this day, I record everything in my head before I commit to a photograph.”

For Baccari “Every image is a prayer,” and ended his evening talk: “The greatest gift a camera can give a serious photographer is that of seeing, and through seeing, understanding a little more about humanity, the significant details of life, and the world around us. And in the hands of a perceptive person, the photographer’s work becomes an art form.”

I regret that I had not met Alessandro Baccari earlier in my life and treasure the short time we spent together. What started as a photo essay assignment, ended in a deep connection of the heart. He was a very special person who illuminated and inspired me with his gift of loving friendship. He was truly a man of purpose who lived with integrity, compassion, and love for his fellow humans, regardless of their heritage.

Nobody is truly gone as long as we remember them. Grazie mille caro amico. Ti voglio tanto bene.