By Chris Roberts

Traveling from the Sunset district to the Richmond by foot requires nothing more than a trek through Golden Gate Park. It’s a pleasant stroll, unless you do it at night, in which case it’s a test of nerves.

I’ve only done it once and it was spooky: Noises emanated from every bush and tree, I could hear voices, I could see figures, but nothing stayed out of the shadows long enough for me to figure out what it was.

“There’s something in there,” I said later to anyone who would listen. And anyone who would respond usually gave the same answer: Of course there is. It’s called homeless people. They live in the park. What, did you just move here? Idiot.

But that wasn’t it, I insisted. And as I found out, I was right. There is something ancient and mysterious in Golden Gate Park — and it’s connected to a few of San Francisco’s most famous figures.

Legendary park superintendent, John McLaren, was a master horticulturist and forester who designed Golden Gate Park, and lived in it, too, until his death at 96. His intention was for the park to be a place for all people to congregate and to recreate.

And also to worship.

McLaren, a Scot by ancestry and a Presbyterian by creed, is thought to have brought more than a mastery of horticulture to the Americas. He may have been a little bit pagan.

Nobody really knows for certain, of course, but it’s a theory. And a convenient one. It would help me explain a few things: namely, why exactly one of the oldest active druid circles on the West Coast is in his park.

The San Francisco Examiner isn’t an occult newspaper, but it’s where I find my first clue about the local pagans. “Nice people who like to wear robes and put twelve rocks in a circle and call it a church” worship in the park, an April article reads. Druids in the park? That’s a new one… but believable. This is San Francisco, after all.

Who are these druids, and what do they do? The article didn’t say much, except that a city worker disturbed one of the druid circles, moving rocks around in order to build a retaining wall. Soon after, more workers — quickly and with no questions asked — returned the stones to their proper places apparently requested to do so by the druids.

I had to know more. So I do what any self-respecting investigative journalist would do.

I google.

I search for “druids,” “San Francisco,” and “Golden Gate Park,” and find a website for the international governing body for pagan practitioners. I also find sites for the Golden Gate Park pagans — with names, email addresses, meeting times, and photos of folks in robes, wearing crowns of flowers.

I have plenty to work with. That is, until one day, about a week later, it’s all gone: error 404, website not found.

What is going on? Had I imagined it all?

I’m sitting with Rodney Karr, PhD, who up until I contacted him was the caretaker of what is known to the druids as Monarch Bear Grove.

He appears to be about 60 and sports a plaid vest, in what looks like a Scottish tartan over his oxford shirt. He could be a Celtic musician as easily as a psychotherapist (the latter of which he is). We’re in his office in a big Victorian home on Divisadero Street surrounded by tapestries, carved masks, and religious figurines of every creed.

Rodney is a druid elder. It took a while for Rodney to agree to our meeting — he wanted to know exactly what kind of story I was trying to write. Druids are welcoming to newcomers, he explains, but still wary of outsiders and the attention they bring. But far from being cagey, Rodney is open with his thoughts and generous with his time once we sit down. He offers me tea, and as I sip my Earl Grey, Rodney relates his story. He was a successful entrepreneur who owned beautiful Victorians until 15 years ago when a crisis (he won’t say what, even when pressed) caused him to lose everything. He was forlorn and dealt with it by walking in the park. Somehow, he found himself meditating underneath a few oak trees, near a pile of limestone rocks.

Those rocks form the druid circle in Golden Gate Park. Rodney took the websites down because it was time for change. It was the stones that told him so.

Druids defy a universal definition. One druid’s favorite ritual might not be another’s way to worship at all. But every pagan recognizes how special the Monarch Bear Grove is, for three reasons: the trees, the bear, and the stones.

Most important are the trees. Very old, tall, gnarled live oaks surround the stones. Oak groves are a druid’s temple, mosque, or church.

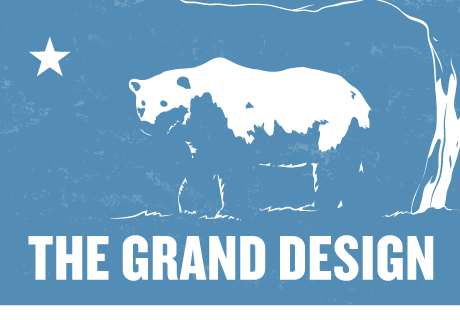

Then there’s Monarch the bear. Every druid respects and loves the spirits in animals as well as trees, and understands that every living thing leaves behind energy, even long after it has passed onto the next world. But this particular bear is special.

Every Californian has a connection to Monarch; its image is on the state flag. The bear is also a permanent resident of San Francisco, stuffed and set behind glass at the California Academy of Sciences, very close to the druid grove where his cage was when he was alive.

Monarch was caught in the woods near Santa Barbara at the request of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst and lived for 30 years in an animal enclosure in Golden Gate Park, a cage that McLaren’s architects had built in the oak groves.

It’s not necessarily significant that Monarch was a bear, even though bears are a member of the druidic pantheon of animal spirits. From a druid’s perspective, Monarch could be a giraffe, a deer, or a particle on a wave, and the worship of nature would continue on much the same. But Monarch did live below the oak trees, and his unique energy permeates the area. Thus, it is he who is honored in this particular druid circle, the Monarch Bear Grove.

Along with the bear, Hearst also brought the druids their stones. He had intended to build a castle near Mount Shasta using stones from a medieval Spanish monastery he purchased and had shipped to California. The Great Depression put the castle project on hold, and the stones were dumped in Golden Gate Park, near Monarch’s cage. They were left to gather moss in the park, forgotten. At least by Hearst.

Was it a coincidence that a powerful animal spirit should be incarcerated in a druidic church — the oak grove — at the very same spot where a heap of mystical stones should be dumped? Not according to the druids. There are no coincidences, they say.

“Monarch Bear Grove is a temple, just like Stonehenge is,” Rodney tells me. “When things happen there, we listen to them.” That the stones were moved by the park worker told Rodney that he, too, should move, dismantle the websites, and hand over stewardship of the grove to someone else. “But that they were replaced so quickly told me something, too. That we should continue our mission at the grove.”

Rodney thinks that San Francisco pagans began to secretly worship at the grove beginning in the 1920s, coming out only at night to avoid detection and the societal stigma that would be sure to follow. Was McLaren among them? “Probably,” he says. “That there’s a major druid grove in the middle of a major city, that’s really incredible,” he adds. “But it goes back to McLaren, and what his vision for the park was.”

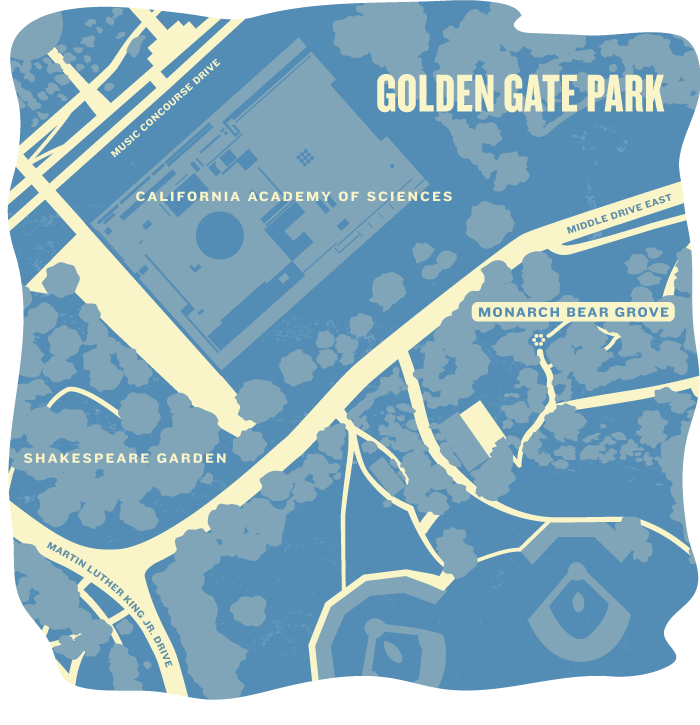

After hearing so much about this holy space in Golden Gate Park, it’s time to see it for myself. “We’re standing in the bear cage now,” my guide Jehanah, a druid elder, tells me. We’re on a trail in the park, within sight of the de Young Museum and the living green roof of the California Academy of Sciences. Jehanah is a kind, smiling, gray-haired woman who appears to be in her 60s, the kind who migrated to the Haight-Ashbury in her 20s and stayed. She looks the part of an old hippie: a hemp bag with an om symbol matches her green corduroys, and she stops every few steps to compliment a tree or a flower. She also runs a poetry night every Wednesday at the Sacred Grounds Coffee House near the Panhandle. Jehanah walks with a cane in one hand, but keeps stride with me, even as she totes a plastic bag full of eggs, seeds, and fruit in the other.

I’ve come with her to leave food for the animals, say hello to the trees, and get in touch with the spirits of nature. In a word: worship.

“Every time I go out, it’s a little bit different,” Jehanah says. She’s sitting in the middle of one of the circles. She points out a “ghost tree” — where an old oak once stood before park workers cut it down. “You probably can’t see it,” she says. As we talk, squirrels dart in and out of the stone circles grabbing seeds. Above, a few ravens sit perched in trees waiting for us to leave so they can dive down and grab the eggs we’ve left.

Being a druid isn’t occult at all, I’m finding out. It’s has to do with being a part of the land and nature. It requires very little, just a spot outdoors and some peace and quiet.

Even the stones aren’t really necessary, though there’s definitely something in them.

“The stones are alive, too, you know,” she says. “They’re just moving more slowly. We’ll all be stones someday.”

Take a walk through Golden Gate Park — in the daytime, preferably — and follow the energy waves. Follow them to JFK Drive, near the National AIDS Memorial Grove. Look for the oak trees. Sit on a rock and ponder how it was that William Randolph Hearst’s bear and monastery stones were both in the same spot. Refresh with a cup of coffee at Sacred Grounds, maybe on a Wednesday — when you can experience Jehanah’s poetry readings. Connect all the dots within and without with a psychotherapy session with Dr. Rodney Karr. No robe required, just an open mind and willing spirit.

Design: Wilfred Castillo