Pride as it exists today elicits a mixed bag of emotions. On the one hand, it’s heartening to see so many businesses present such a public pro-gay sentiment that could very well talk a young queer person off the ledge. It’s undeniable that seeing yourself represented and embraced in the mainstream can be validating and encouraging.

On the other hand, it can be an absurd waste of money for companies to tell the world they celebrate Pride when those dollars could be given directly to a community in need. My time spent working for a huge corporation that throws millions of dollars into an annual, monthlong Pride blitz has been disillusioning to this end. Why not sacrifice all the pomp and circumstance for an opportunity to take real action and actually show your solidarity with the queer community?

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best content about life in the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

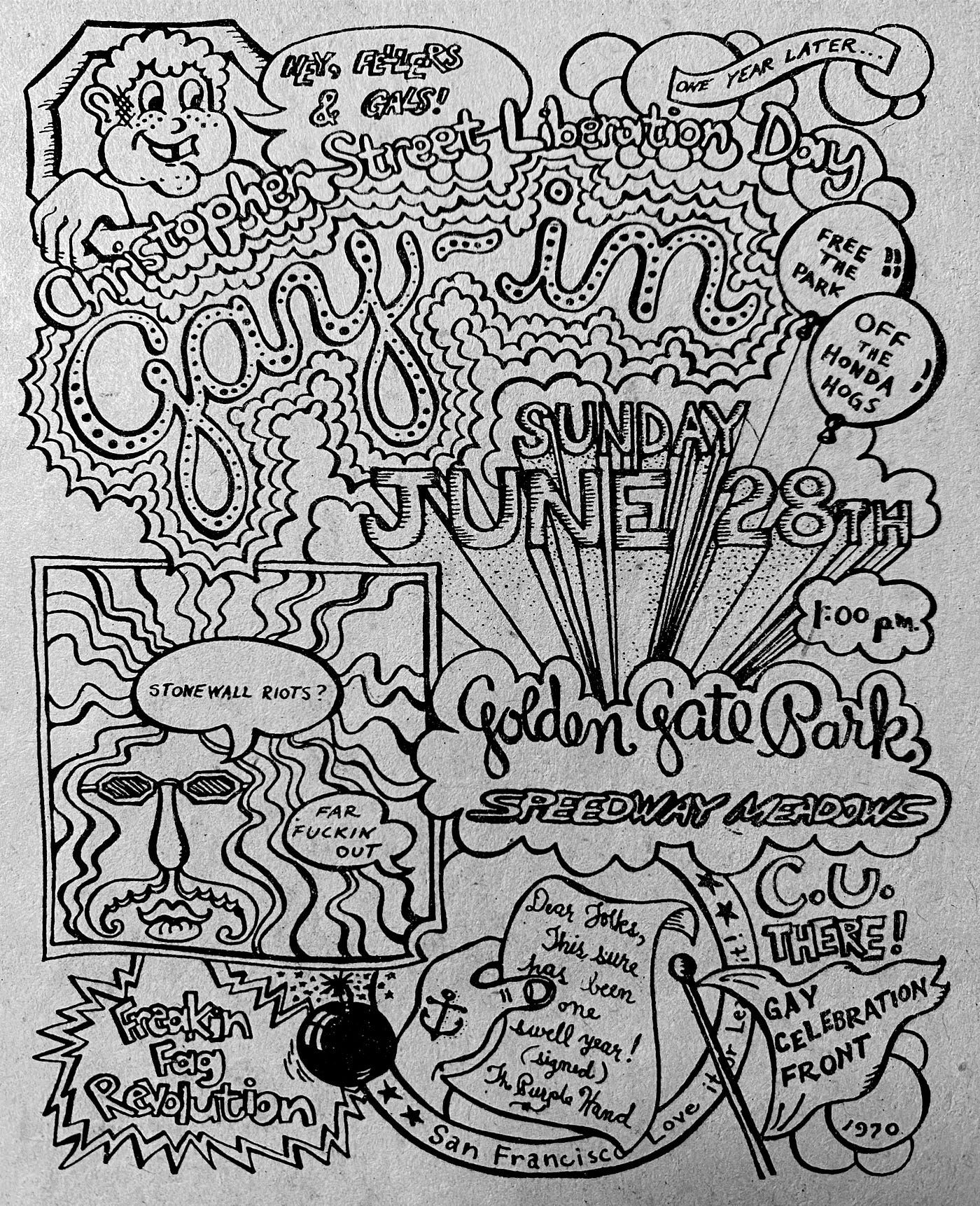

Pride began in San Francisco in 1970 as a march down Polk Street followed by a “gay-in” in Speedway Meadows at Golden Gate Park in solidarity with the previous year’s Stonewall Riots. It was actually the first Pride celebration to be held, a day earlier than Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City. The earliest iterations of Pride, from 1970 to the mid 1990s, were bold displays of the courage it took to be gay in the face of a society that didn’t care to understand queerness. The first days of Pride were jubilant showcases of resistance, rebellion, and radical self-expression. They were direct actions against oppression.

With in-person Pride celebrations (which would have been this weekend in San Francisco) canceled due to Covid-19 and a huge surge in anti-racist revolutionary activity, it’s a more important time than ever to think about what Pride means.

As a designer, I thought about how I could contribute to this cause. So I worked on a project called Pride Is a Protest that aims to elevate the potency of intersectional organizing. This project is a part of the San Francisco Arts Commission’s Art on Market Street kiosk poster series, responding to this year’s theme, “Celebrating 50 Years of Gay Pride.” From now until August 31, 36 unique posters telling the story of LGBTQ+ activists and history will be on display around San Francisco at Muni bus kiosks along Market Street, from Embarcadero to Civic Center. (View a full map of the poster locations here.)

My goal for this poster series is to recenter the narrative of Pride away from pinkwashing and rainbow capitalism to its roots as an act of protest.The posters employ a black-and-white color scheme to be visually alluring and starkly frame the content against the Technicolor backdrop of San Francisco, highlight the relationship of the pieces to each other as a series along Market Street, and make a statement — a protest — against the over-rainbowfication of Pride.

The 18 front-and-back posters are intended expose the public to the individuals, places, and protests that have made San Francisco a global epicenter of queer life. I sought to represent the full spectrum of our queer community and highlight as many lesser-known narratives about our various subcultures as possible.

By centering stories of resistance, the project tries to recapture some of the brave and defiant ways in which queers have liberated themselves and demanded their own freedoms over the past 50-plus years. I focused on the many firsts that have occurred in San Francisco, from the first National Deaf Gay and Lesbian Center to the first openly gay man to run for public office to the world’s first queer theater company.

We’ve known this all along: No one is coming to save us. It’s on us to save ourselves. We have to take our collective freedom into our own hands.

Below are a selection of seven people, places, and protests memorialized in this project. You can find more information about all 18 subjects here or by watching a recent talk I gave at the GLBT Historical Society.

I’m also on Instagram @PrideIsAProtest. After the installation portion of project is over, I will be evolving the account into a platform for racial and social justice .

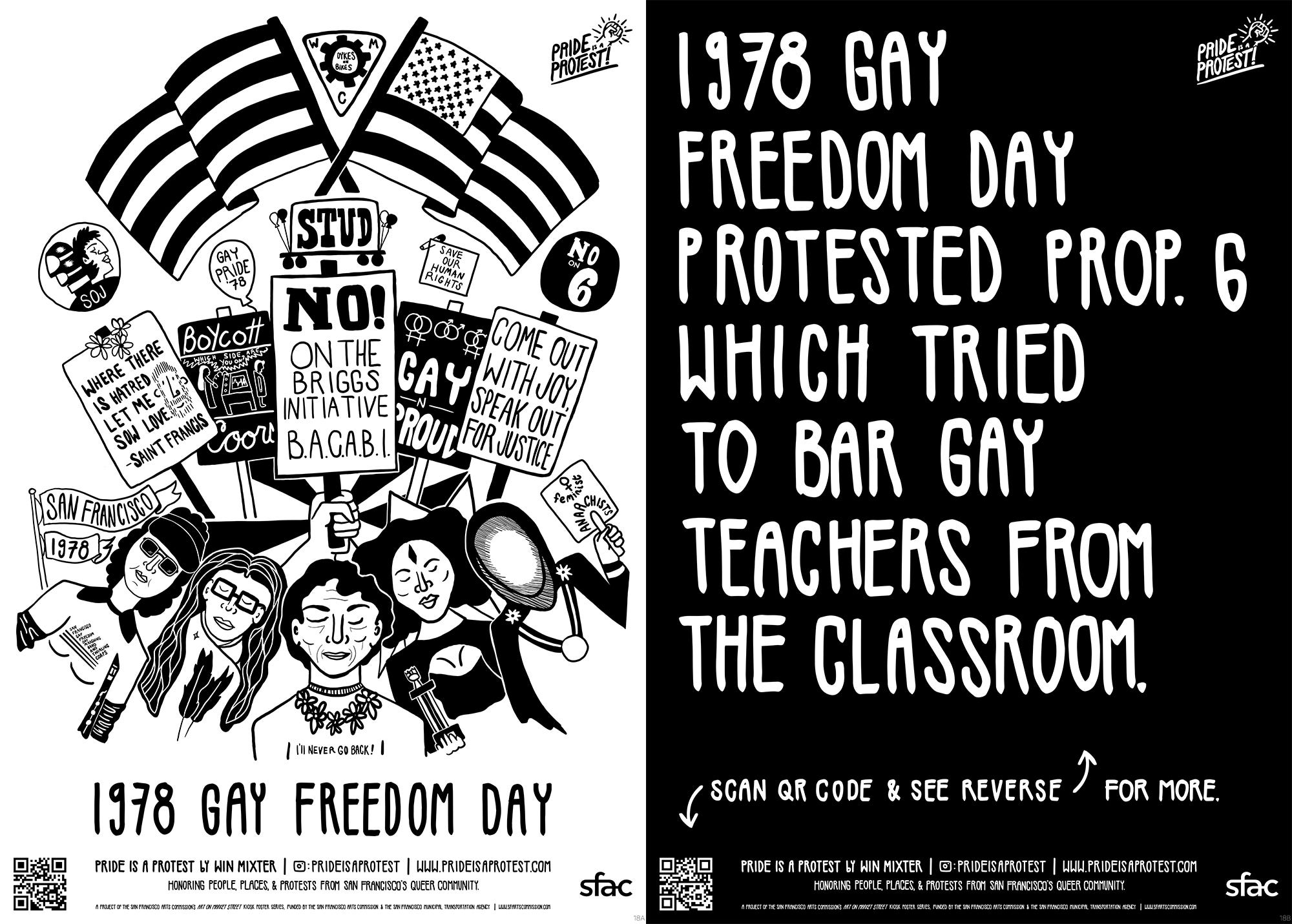

Gay Freedom Day

The 1978 Gay Freedom Day was the ultimate example of “Pride Is a Protest.” Not only were queers protesting CA Proposition 6, which would have barred gay teachers from the classroom, but they were also boycotting Coors, which employed controversial and exclusionary hiring tactics in which prospective employees were subject to a polygraph test and asked questions about their sexuality; queers were not hired.

It was also chock-full of firsts: the first appearance of Gilbert Baker’s rainbow flags; the first appearance of the SF Gay Freedom Day Marching Band and Twirling Corps; one of the first documented marketing campaigns by the Club SF Baths, which handed out free balloons that were everywhere. It was also the third appearance of Dykes on Bikes to lead the parade and an early example of internal disagreement between BDSM group Society of Janus and the parade organizers — assimilationist gays didn’t want this to cloud their march toward acceptance.

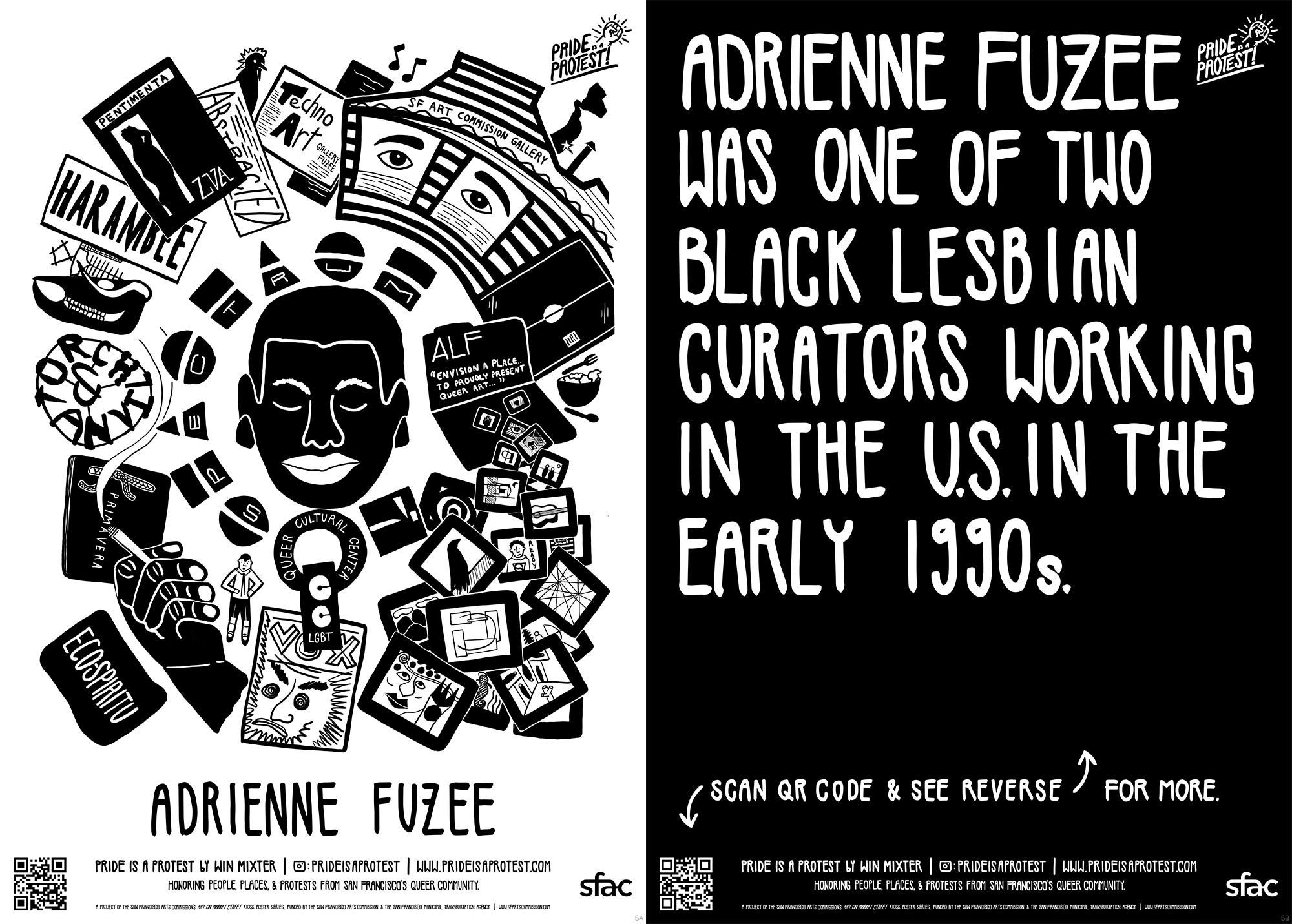

Adrienne Louise Fuzee

Adrienne Louise Fuzee (1950–2003) was one of two openly lesbian African American curators working in the United States in the late 20th century. She lived and worked in the Bay Area from high school onward. She was an educator, poet, author, and musician. Her radical self-expression came in the form of her visionary curatorial practice.

Fuzee was most active in the early to mid-1990s, curating shows that focused on computer-generated art, contemporary abstract art, and sculpture.

She was also a very reflective and personal author, penning journals’ worth of poems, found at the archives, as well as evocative curator’s statements for each of her shows.

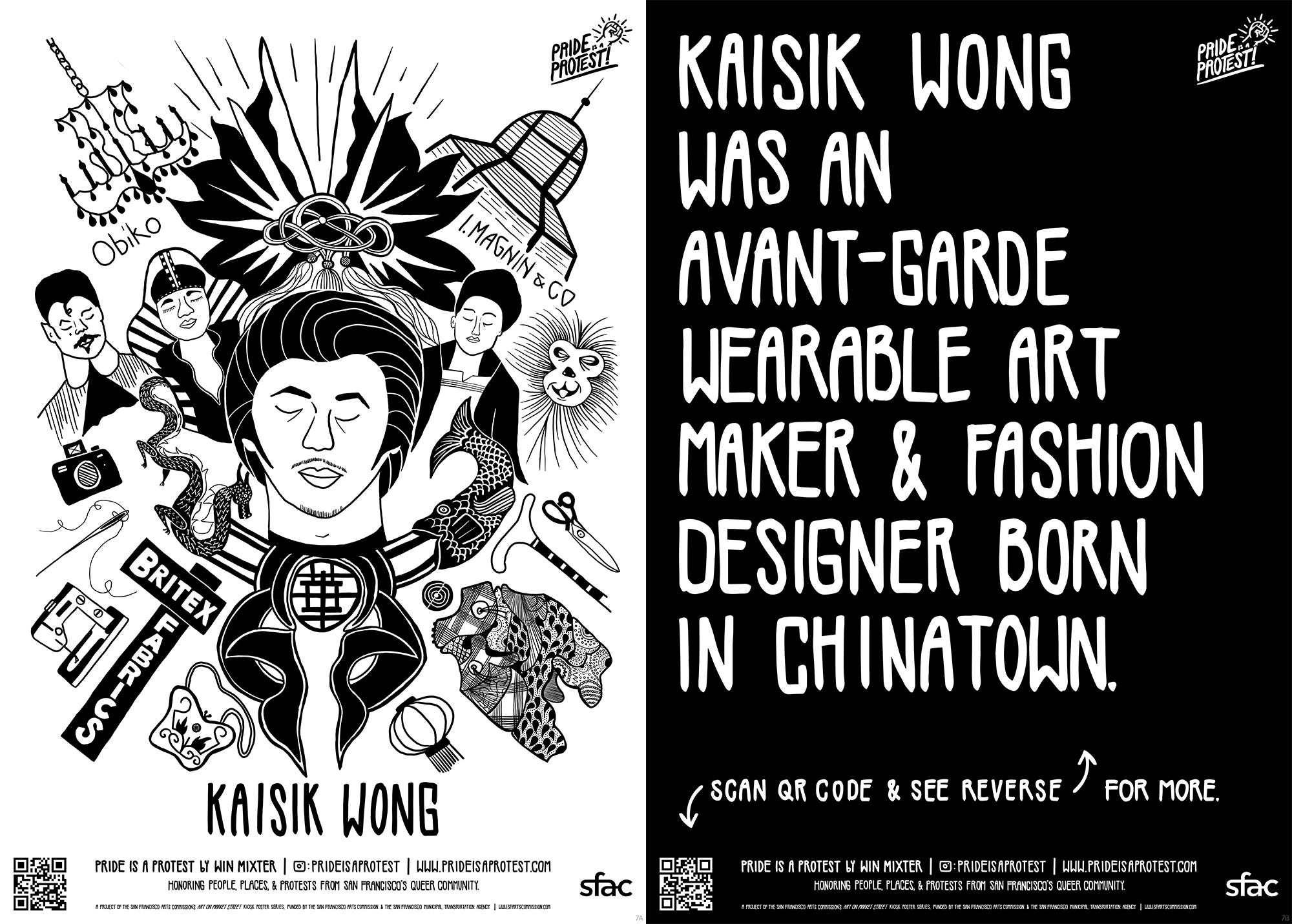

Kaisik Wong

Kaisik Wong (1950–1990) was an avant-garde Chinese American wearable art maker and fashion designer born in Chinatown, San Francisco. Despite a relatively low historical profile, he created custom designs for stars like Elton John, Tina Turner, and Angelica Huston. He was was a collaborator with Steven Arnold, famed Cockette originator and Salvador Dalí protégé.

Despite several forays into the business of fashion, including a ready-to-wear line called MuunTux and a brief stint in New York, Wong’s psychedelic, collage-style garments were a mismatch for the rigors of commercial fashion. He created wearable art.

Wong was thrust into the international spotlight a decade after his death when Nicolas Ghesquière, then the lead womenswear designer for Balenciaga, copied a Kaisik-designed vest for a pair of dresses in the company’s 2002 spring collection. When confronted with the plagiarism, Ghesquière simply said, “Yes, I did it.” There were zero repercussions to his credibility or his career—yet another white man stealing creative ideas from a POC designer.

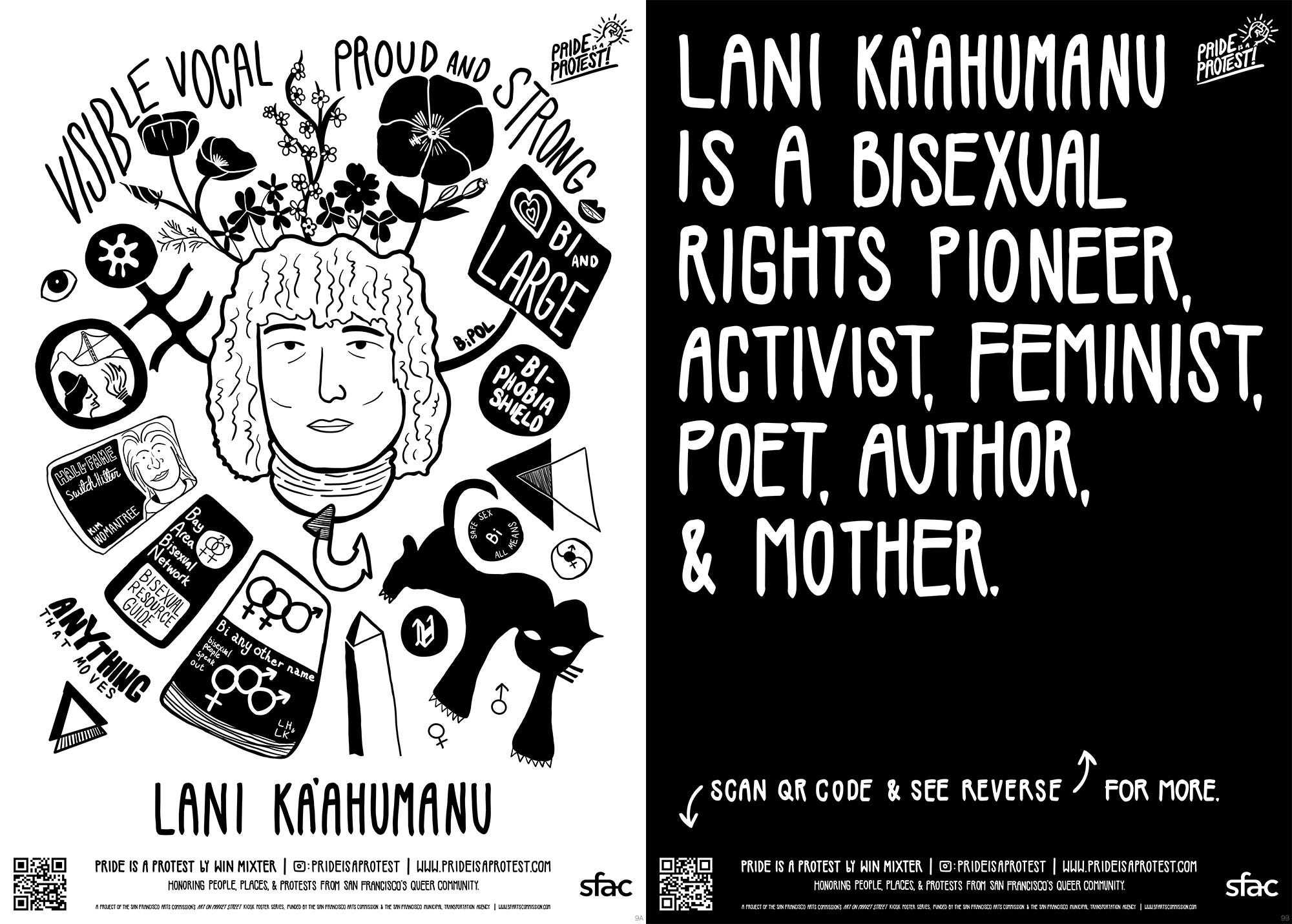

Lani Ka’ahumanu

Lani Ka’ahumanu (b. 1943) is a bisexual rights activist, poet, author, and mother. She is considered one of the foremothers of the bisexual rights movement, which began in earnest in the 1980s. She originally came out as a lesbian and moved to San Francisco in 1974, leaving her two children in the care of her ex-husband. Ka’ahumanu later came out a second time as bisexual after falling in love with a man who also identified as bisexual. She helped found the San Francisco State University Women and Gender Studies Department.

Ka’ahumanu was the sole bisexual speaker at the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation, speaking last. Organizers forced her to cut her speech drastically short moments before she was due to go on, but her words echoed powerfully across the national mall: “It ain’t over till the bisexual speaks!”

Klubstitute

Klubstitute was a weekly queer punk underground happening staged in San Francisco in the early 1990s. It was the brainchild of Michael Collins, aka Diet Popstitute, and his band of co-conspirators. His band, The Popstitutes, included author Alvin Orloff and Tyler Ingolia.

Klubstitute’s resistance came from the way it provided space for radical self-expression and as a gathering place for ACT UP and other activists. Its patrons embraced the DIY aesthetic of San Francisco—a kind of club-kid look with a grungy punk overlay. Klubstitute was a mashup of different artistic and creative genres, ranging from spoken word and comedy to punk rock and play acting.

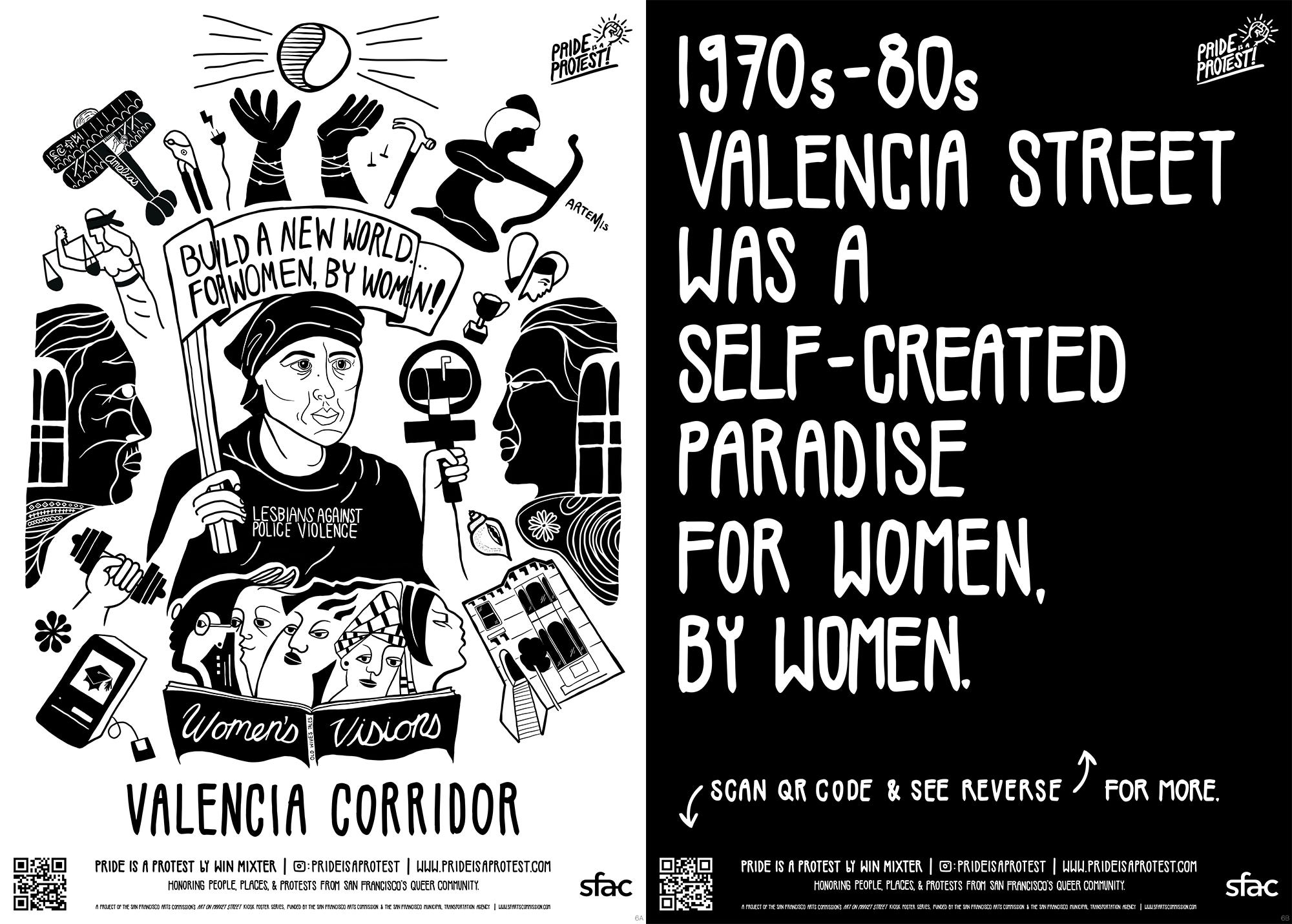

Valencia Corridor

In the 1970s and 1980s, Valencia Street in the Mission District was a daring microcosm of the queer community, a safe corner of the city carved out by visionary lesbians who sought freedom from the constraints of heteronormative mainstream culture.

Women did everything for themselves, from blue-collar trades like construction and electrical work to white-collar office jobs in the fields of law, medicine, and beyond. Creative collectives that focused on self-publishing literature, resources, and artwork for, about, and by women sprung up in rapid succession.

Lesbians also came together to protest police harassment in this era. An especially traumatic incident occurred in 1979, when intoxicated off-duty San Francisco Police Department officers forced their way into Peg’s Place, a lesbian bar in the Richmond District, and beat bloody the bar owner, the doorwoman, and several patrons. It was yet another reason lesbian women yearned to carve out a place of their own.

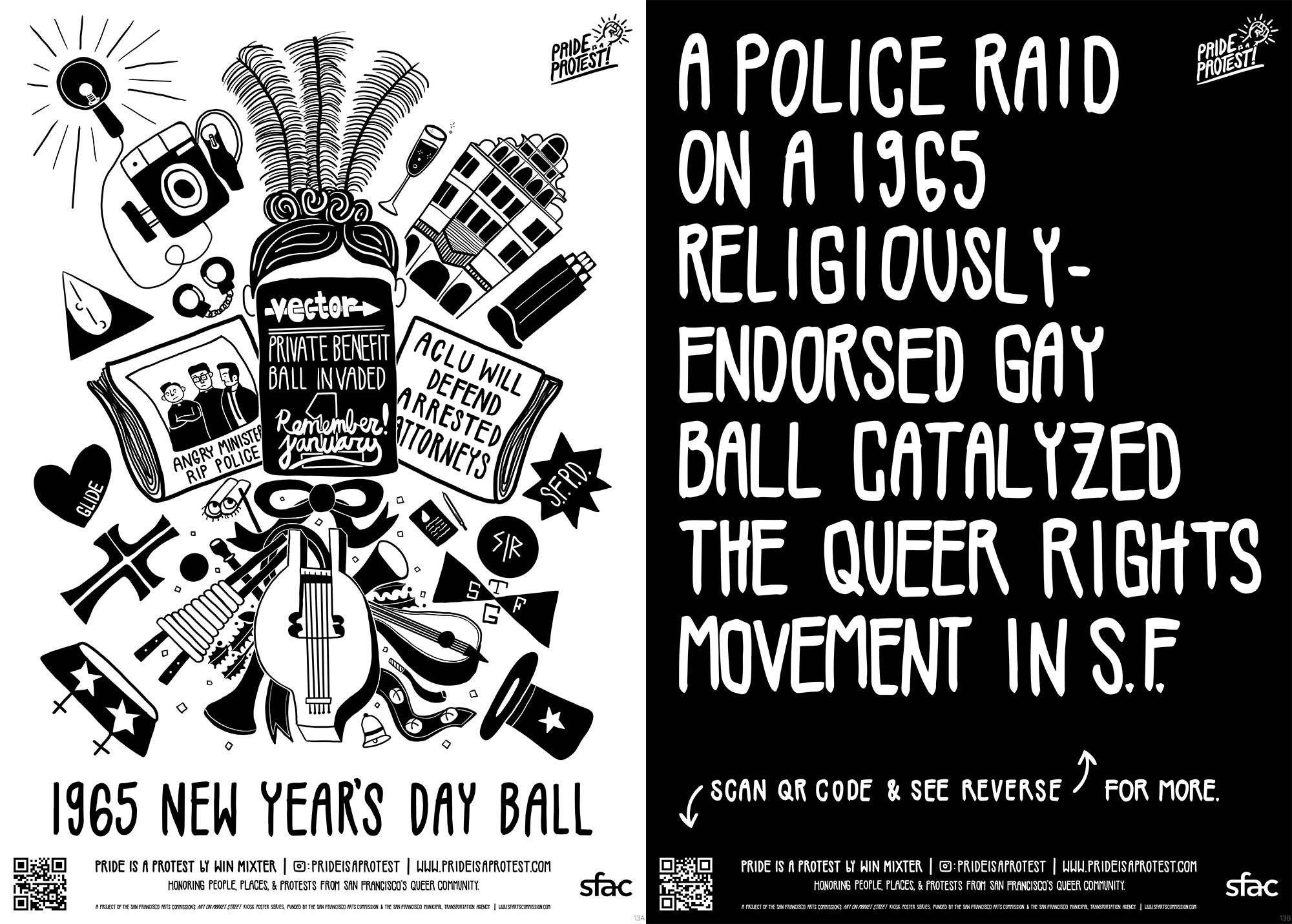

The 1965 New Year’s Day Ball

Called “San Francisco’s Stonewall” by the Bay Area Reporter, the 1965 New Year’s Day Ball gathered together San Francisco’s six homophile groups to co-sponsor a dance on New Year’s Day 1965 to raise funds for the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH), a group founded to encourage a dialogue between the church and various gay rights organizations in the 1960s.

The event was sponsored by ministers from Glide Memorial Church, whose clergy were organizers of the CRH. Private dances were a way for queers in the 1960s to circumvent stifling laws enforced by the SFPD that prohibited touching and dancing between members of the same sex in San Francisco public spaces.

Proper permits and liquor licenses were applied for and approved ahead of time. The CRH clergy also met with police beforehand to ensure there would be no harassment. When revelers began to arrive on the evening of January 1, 1965, however, they were met by a substantial contingent of SFPD officers and photographers intended to intimidate and expose attendees, particularly those dressed in drag. Police arrested three gay male attorneys and one female secretary on obstruction charges when they challenged continued police entry into the private event.

The ACLU later represented the attorneys in court, and the mainstream media picked up the story. All three defendants were acquitted when the judge threw out the trial — a monumental victory for queers in San Francisco and around the world.