When the first round of urban settlers came to the Mission in the 1850s, the landscape was not flat. There were streams, grassy rolling hills, and wetlands. The area between Division and 20th Streets had so many creeks that it was faster to get downtown in a small boat than try to walk — otherwise you’d risk getting your boots stuck in the thick mud of the swamps.

Swampiness aside, Valencia Street was a citywide destination for diversion. It was famous for its dense collection of saloons, restaurants, specialty shops, and apartments. This early Valencia was built directly over the saturated mud of Arroyo Dolores, the creek that ran down where 18th Street is today.

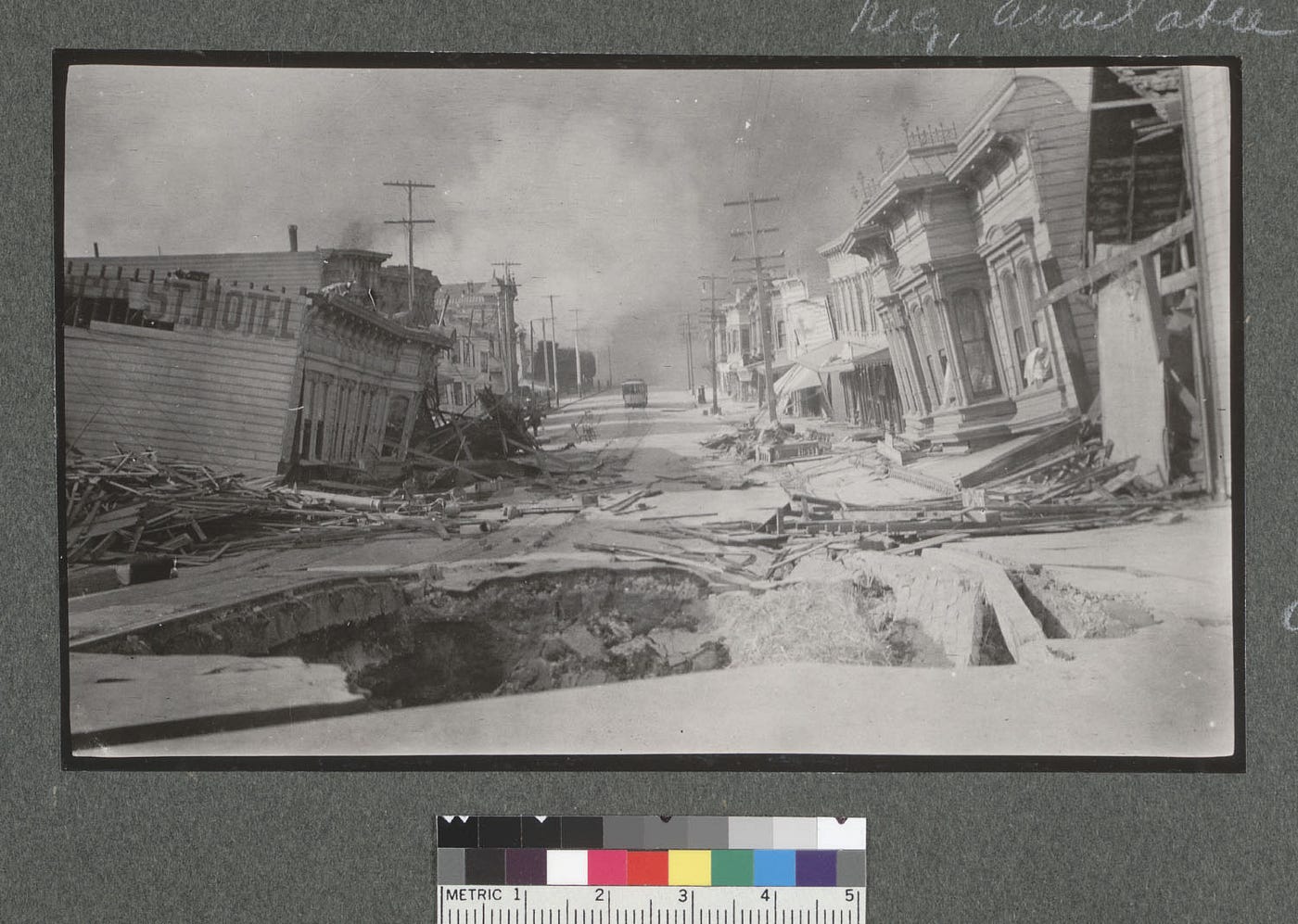

Wet soil acts like liquid when it vibrates, so on April 18, 1906, when the great earthquake struck, mud became quicksand, collapsing and swallowing up buildings. Gas lines broke and flames went up, spreading into a giant firestorm. The inferno incinerated everything in its path, including Valencia Street, until it reached 20th Street, where it was fought back by the only working hydrant left.

After the disaster, higher parts of the city were cleared and used to fill in lower parts. Since the northern end of the Mission was low and soggy, the remains were left in place and rubble was hauled in to fill up the area. Some six feet below the current street level remain what is left of the saloons, restaurants, shops, and homes that occupied the same footprint before the fire. Like the ruins of Pompeii, everything stayed where it was — covered over by soil. That catastrophic moment in time lies intact under today’s Valencia Street.

During most of this year I have been working on a construction project right in the middle of the block at Valencia and Albion between 16th and 17th. This project involved a lot of excavation, like the pit shown above. I was intrigued by the tons of remains I found. I marveled at how easy it was to see the layers of history in the soil. As I kept digging up objects, I couldn’t help but wonder who these things had belonged to. Piecing together information I found in the 1905 Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory and the 1905 Sanborn-Perris San Francisco Atlas, I was able to get a better idea of what the objects were and who they might’ve come from. Below are some of the things I found.

Then as now, many stores lined Valencia that catered to Edwardian consumption. A. J. Dehay & Son Liquors sat where We Be Sushi (between 16th and 17th) is today. Emile, one of the sons, lived upstairs with a clerk, Albert Mourot, from his store. A dry goods store, Rauhut Brothers, sat at 508 Valencia St. and sold the kinds of things you’d expect to buy at Walgreens today.

In the wake of the fire, nearly all the wood of the buildings burned away leaving only hardware, ceramics, masonry, and stone. Before the fire, Eastman Brother’s Hardware occupied the location where Thai House 530 is today. One of the brothers, George, lived upstairs with a clerk, Bertram Shephard, from his store.

Desmond Elsworth, the owner of a marble company, shared a flat with the owner of United Construction Co., Joseph F. K. Carpenter, over where El Toro is now. On the opposite corner of the block, William S. Rhodes, another construction contractor, lived with his foreman Rudolph Leonhart in 508b.

At the time of the fire, electric lights were not always reliable. Gas, kerosene, and candles were still popular sources of light. Two lamplighters named Harold and John McCarthy lived over the shop at 572 Valencia Street.

PG&E became established the year before the fire but had a number of competitors. The earthquake and fire ruined all the power companies’ gas and electric infrastructures. But lucky for PG&E, its Potrero power plant was unharmed. This competitive advantage ensured that this one power company became a monopoly during the city’s reconstruction.

Saloons were an important part of the raucous character of the neighborhood. Before the fire there was a watering hole and liquor warehouse where the 16th Street entrance to Sunflower is now, and other similar establishments where Blondie’s and El Toro are today.

First, San Francisco was a city of only men. Then after building a settlement, the pioneers began to send for their wives, but it took decades before there were as many women as men. By the time of the fire, the city was established enough to be fit for families.

Where the Money Mart now occupies the corner of Valencia and 16th, Edwardian children once gazed into Cokales Candies store windows. Mrs. Sarah Markowitz sold toys where Urchin Bistrot is now.

The center right bottle shown in the photo above is Miss Winslow’s Soothing Syrup — a morphine syrup given to teething babies to stop them from crying. It played a key role in the formation of the FDA because it was revealed to have caused the death of millions of babies and stressed-out mothers. A druggist, Rodolphus W. Coffin, worked at the corner of 16th and Valencia and lived two blocks down Valencia near 18th St.

At the turn of the last century, horse-drawn trolleys and buggies were the most popular form of personal urban transport followed by walking and bicycling. It wasn’t until the burned city was rebuilt in the early teens that cars outnumbered buggies.

A horse outfitter named Alfred Schudel made harnesses for draft horses where furniture store Monument (572 Valencia Street) is now located. For some reason, one apartment over where Blu Dot is now was rented exclusively to horsemen. A teamster, a stableman, and four drivers lived there together. A bicycle shop occupied some of the space where West of Pecos is today.

Outside the city, vast farmlands occupied most of the Bay Area. Fresh local organic produce was carted in daily. Henry C. Tonnemacher ran a grocery store where El Toro is and lived over modern-day Frjtz.

Animals were butchered outside the city center at “Butchertown” in the Bayview. There the Islais Creek would carry away all of the putrid horrors that come with butchery. Before the fire, the charcutier Charles Selinger made sausage where Blu Dot is today and lived overFive and Diamond. Hugo Futterer ran a smokehouse preserving meats where Limón is now.

In the days before ready-to-wear, most clothes were made by tailors or dressmakers, such as Rein Anema, a tailor who lived in one of the apartments over current-day Blu Dot. The Deering Brothers, George and William, sold shoes and lived where Puerto Alegre is now. In the building next door where West of Pecos is, Dennis F. Riordan fixed shoes at California Shoe Repair and lived around the corner on 17th St. and Capp.

John Hondet lived and operated a hand laundry shop where Frjtz is now. Around the corner, the huge mechanized laundry complex Metropolitan Laundry took up the corner of 16th and Albion where Delirium and the Roxie Theater are today. A bunch of laundrymen who worked there lived on the block, including assistant manager William Biggie.

It is chilling to imagine the remains of many homes and livelihoods interred under modern Valencia Street. Our city was given to us by the many people who came before. People lived here, people died here, and people live here again. It is important to honor the humanity whose blood, sweat, heartache, and perseverance built our city.