Death and burial

By Beth Winegarner

When Angie Cope’s mom died last year at the age of 69, Cope wanted her mom’s remains handled in a way that was true to her ideals. Ann Taylor — a longtime Silicon Valley worker — loved dancing, being outdoors, and running, particularly on the beaches in Pacifica. Cope chose one of the most planet-friendly options she could find: Aquamation.

Aquamation, also known as water cremation and alkaline hydrolysis, is similar to cremation in the sense that a person’s remains are reduced to powdered bone. But it doesn’t require harvesting and burning wood, or releasing smoke and chemical emissions into the atmosphere, making it more environmentally friendly.

“I’ve researched how caustic burial is,” Cope said, referring to commonly used embalming chemicals. “And cremation is not much better.” Taylor originally asked to be cremated, but Cope landed on aquamation after discovering the process among other “green” alternatives. Her mom’s friends and family said she would have loved it.

You cannot bury loved ones in San Francisco since its ban in 1901. The popular option is to lay them to rest in Colma. While you can cremate, aquamation is a rare alternative only available to us locally in the last three years.

California legalized aquamation in 2017, and the law went into effect in 2020. At the time, Christopher Taktak was in his junior year of an Urban Studies program at Columbia University in New York. Suddenly thousands of people were dying due to Covid-19, he learned about aquamation, and his priorities shifted. Taktak graduated early, came to California, and founded Pisces in January, 2022, to offer water cremation services across the state.

During aquamation, the deceased’s body is loaded into a stainless-steel cylinder, which then fills with 400 gallons of liquid, 95 percent water and 5 percent alkali salts (commonly known as lye). Over the next four hours, as the heated liquid swirls around the body, all of the soft tissues are dissolved. This fluid, once its pH is neutralized, can be used as a kind of liquid fertilizer; it contains all the macronutrients the body once held.

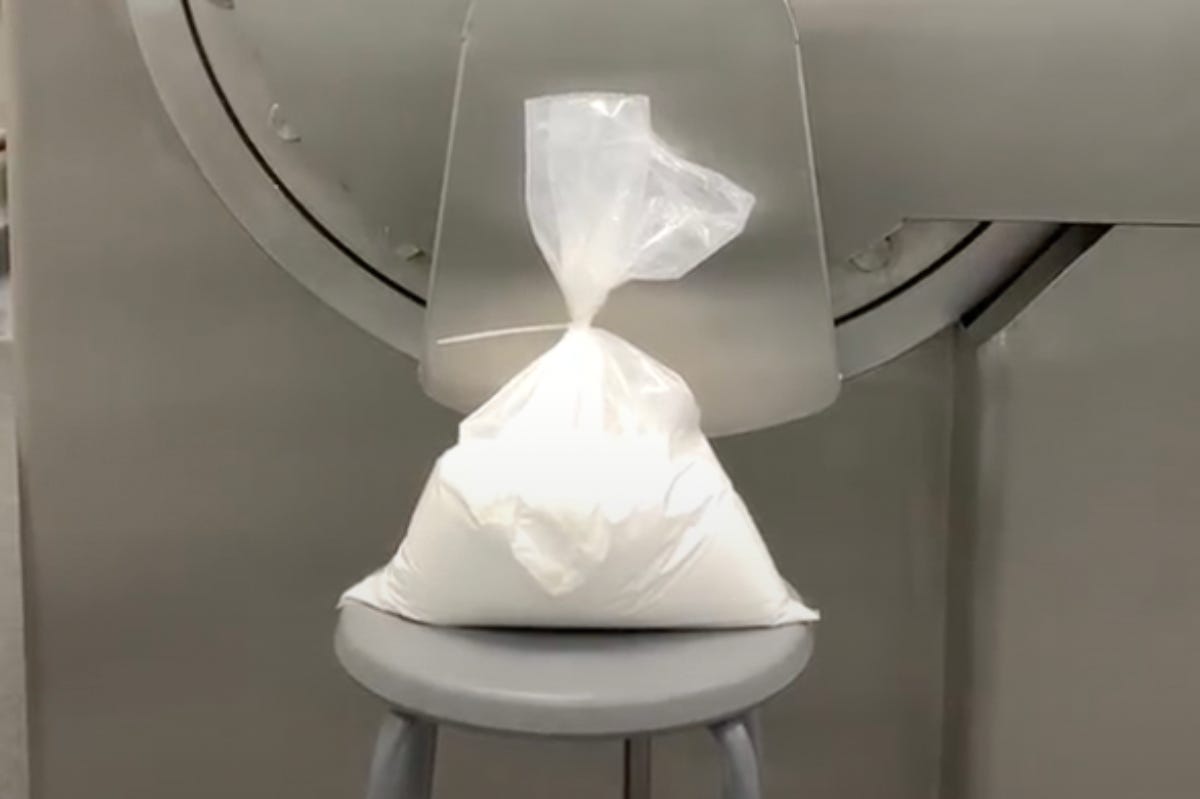

The now-brittle bones emerge pure white, and are turned into powder, as with cremation. “Some customers compare them to pixie dust, confectioner’s sugar, or snow,” Taktak said. “They’re lovely to look at.”

The whole process costs $3,850 with Pisces. Direct cremation without any funeral or burial services costs almost $2,000 in San Francisco, while burial costs an average of $7,000 to $10,000. Even though it’s a bit more expensive than cremation, Taktak said people are seeking more eco-friendly options, and aquamation uses 90 percent less energy than cremation.

Since the process was legalized in California, 46 people in 2022 and 15 people so far in 2023 have chosen aquamation for themselves or a loved one. That’s just a fraction of a percent of deaths, according to data from the California Department of Public Health.

That’s likely to change as more people learn about it. Nationwide, 2.5 percent of people said in 2023 that they would choose aquamation, according to the National Funeral Directors Association. Another 40 percent said they would choose cremation, 25 percent wanted a casket burial, and about 16 percent chose a green burial or composting.

For now, Pisces picks up bodies across California and takes them by van to Seattle, Washington, where its current aquamation facility is located. Taktak admits that isn’t ideal, given the emissions involved in transporting bodies 800 miles each way. He hopes to partner with a second facility in Palm Springs soon, and set up a third spot in Sacramento in early 2024. Each machine costs about $475,000, and the permitting process in each city can take months, if not years.

One reason permitting takes so long is that Taktak finds himself teaching officials what aquamation is. This can be an uphill battle, especially after early headlines claimed it “leaves only bones and brown syrup” or that “liquefied people” might wind up “in sewers.”

Caitlin Doughty, the advocate and author behind Ask a Mortician, mobilized support for legal aquamation in California in 2017. She asked her followers to shower Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, then the head of the state Appropriations Committee, with cute animal GIFs while urging her to move the aquamation bill out for a vote. After all, Gonzalez, in her guide for online advocates and campaigns, explicitly asked for animal photos and .gifs.

“I’m not saying it was 100 percent your cat GIFs that did it, but I think they really helped,” Doughty said in a video on aquamation in 2022.

Despite some people’s preconceived notions about aquamation, Taktak feels like he’s on the right path. The established funeral process is “quite antiquated,” and can be “predatory and manipulative,” he said. For a growing number of people, aquamation is “the most benevolent, low-key way to leave the Earth; to leave the Earth with little noise.”

Beth Winegarner is a San Francisco-based journalist and author. Her new book, “San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History” is out Aug. 28.