If you’ve lived in San Francisco in recent years, you know about the honey bear. These cute, stenciled icons are smattered on building exteriors throughout the city. Sometimes, the honey bear wears a cozy beanie. Other times, it’s disguised with 3D goggles and popcorn. Recently, it’s been spotted wearing a Black Lives Matter sweatshirt and mask in response to Covid-19.

For many, the honey bears are a harmless, fun splash of pop art — a symbol of San Francisco’s quirky art scene and the city’s playful appeal. The artist behind the bears, who remains anonymous and is known simply as “fnnch,” has enjoyed a large following, especially on social media, even being dubbed “the Banksy of San Francisco.” He’s responsible for other lighthearted works, such as stenciled dogs (including an origami corgi and a balloon wiener dog) and a series of vibrant lips.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

Since moving to San Francisco from St. Louis in 2011, fnnch has made a name for himself by painting all over the city. His collaborations with galleries and major companies, including J.Crew, LaCroix, and Toms Shoes, have helped to establish his success and reinforce his vision to make art more widespread. His easy-to-digest brand has been quickly embraced — particularly by his 85,500 followers on Instagram — and he has since been heralded as one of the top artists in the Bay Area, gaining praise and recognition for his fundraiser during the coronavirus.

The story of fnnch seems easy, even lovable. Nothing could get f**ked (or should I say, fnnched) up, right?

Enter Ricky Rat, a San Francisco–born cartoonist who was raised by Chicano-Portuguese and Lebanes- German parents across the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County. Ricky has recently and very publicly pushed back against fnnch’s art, which he believes doesn’t deserve the massive recognition it has received, especially over what he views as the “Fisher-Price art” that often displaces the presence of local artists and issues.

“I’m not saying I’m more talented or deserving than fnnch is, because I’m not,” Ricky says. “But there are hella other artists from here, like Lucia Ippolito, who I think are just better. She’s dope, and she’s actually from the Mission. Someone like her deserves way more of that recognition than he does.”

However, it’s a complicated matter. Street art, by definition, is created in public, and is (in theory) open to anyone who is interested in participating. It can be made by any person from any background in any place, and as long as the creator has something to express on their citywide canvas, they can gain recognition and credibility from their independent hustle. There is no official rule book declaring who can or can’t participate or what their participation should look like. And who gets to claim what is good or bad street art?

But this story is more than just an aesthetic feud between artists. (Fnnch has yet to respond to Ricky, so it’s more of a one-sided affair than an actual feud.) Yet, the more you hear Ricky’s viewpoint, his background, and his beliefs, the more it becomes clear that this isn’t actually about stencils and spray paint as much as it is about space, representation, and equitable compensation.

Ricky’s abrasive callout over fnnch’s art represents a resistance against the city’s changing demographics. His opposition to fnnch highlights just how significantly gentrified and divided the city has become due to the unbelievably expensive living conditions for so many in San Francisco — a place where the Black population has been cut in half, to less than 6%; where anyone not making a salary over six figures has to flee; and where homelessness, drug addiction, and mental illness are constantly swept under the rug by city officials despite the concentration of public and private wealth here. Ricky is calling out how fnnch’s art reflects what San Francisco has given newcomers, versus what San Francisco has taken from longtimers.

To be blunt, San Francisco and the greater Bay Area have become a segregated dystopia for some and a curated destination of boutique art for others. And in Ricky’s opinion, that rift is obvious in how the city and its residents idolize the work of street artists like fnnch.

I contacted fnnch for this story, but he politely declined to speak on record. He has, however, told his backstory in past interviews. Fnnch moved to the West Coast to pursue a career in the tech industry, then left to enter the world of art. He flourished, benefiting from a popular, marketable style that eventually allowed him to open his own business and employ a few assistants — an achievement many would herald as successful, unproblematic, and even beneficial to the local economy. Yet Ricky — who has garnered support from other local artists — would disagree, saying it only highlights how disproportionately the city rewards those who reinforce a safe status quo, while rejecting those whose art isn’t as clean or idyllic, but who are instead rooted in the rebellious and revolutionary spirit that has made the City by the Bay what it is. One muralist I spoke with, who was born and raised in San Francisco, went as far as to say fnnch “has been problematic. I don’t like him. Especially that he’s so unapologetic makes us even more mad.” Though social media seems to embrace fnnch, it appears Ricky isn’t the only San Francisco artist with something to say against that. This isn’t a turf war over whose art is more popular; it’s a battle for the livelihoods and visibility of some.

It perpetuated the image that San Francisco is just a place that happy people can come to enjoy, rather than a place that is being systematically dismantled for longtime residents.

Ricky Rat — who teaches art to kids locally — recalls how San Francisco’s culture first inspired him to get into his creative pursuits.

“My dad was a Chicano, and he used to work as a counselor in the Mission with at-risk kids,” Ricky tells me. “I would go with him to work sometimes, and I remember seeing all the art, the people, and the real side of the city, which doesn’t really exist as much anymore, because it has all changed since then. But that always inspired and influenced me and what I’m about.”

Ricky emphasizes several times that he doesn’t think he’s better than fnnch, nor that he is trying to arbitrarily gatekeep anyone from sharing their art publicly. Rather, his beef with fnnch comes down to this:

“I don’t care where you’re from, but if you’re not doing something directly positive that reflects the real community, then I won’t support it. San Francisco has always had a transient population, and the people who come here don’t always have any real investment in our communities, because they can just come and go to build their own shit.”

Simply put, Ricky isn’t convinced that outside artists are always acting in the best interest of local communities — or that when they have, in rare moments, expressed any political views, they have been perceived as gimmicky or performative.

As a born-and-raised Bay Area educator myself, whose mom had to leave San Francisco years ago due to the rising cost of living, I don’t blame Ricky for how he feels. Imagine living in a place your family has fought to remain in and then seeing others literally paint over your home and have their paintings rewarded and praised online, while you’re asked to stay quiet about it and look the other way (something Ricky has alluded to fnnch doing with other artists — though this is purely speculative).

On the other hand, is what fnnch doing really that wrong? Are Ricky’s claims unfounded? What about the fact that fnnch’s art brings happiness to residents and might combat what others see as blight? And what of his recent fundraiser?

Of course, not everyone agrees with Ricky. An anonymous San Francisco resident who is involved in documenting the street art scene in her city said she thinks what Ricky is doing feels overly aggressive and uncalled for. “If fnnch is doing something that makes him and others happy, what’s the point of trying to tear that down?” she asks.

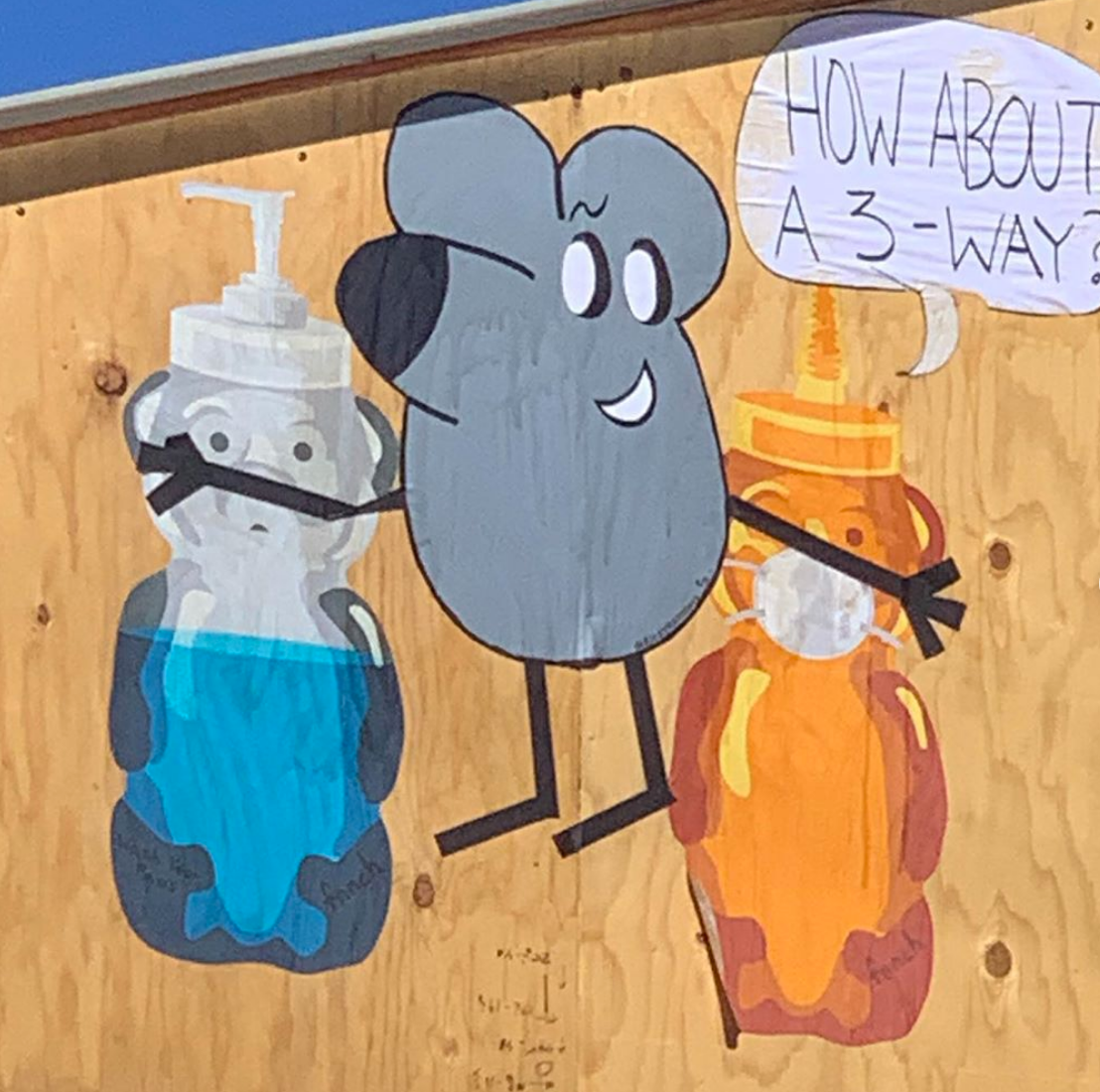

She initially noticed the spat between Ricky and fnnch when she was photographing images for her blog and saw something she had never seen before: a Ricky Rat cartoon painted next to a fnnch honey bear and sanitizer bottle, with the rat’s arms wrapped around both of the other characters, deviously asking, “How about a 3-way?”

Initially, she interpreted Ricky’s art as comical. But then she saw it again. And again. And again. All over the city, wherever fnnch had put up a new bear, Ricky had found a way to subvert it with his rat. And each time, the “attacks” became more direct, and the implications became clearer. This wasn’t some inside joke between collaborating artists. It was one artist with local roots criticizing another artist with established popularity about how the honey bears were tone-deaf to what was actually taking place in the city’s socioeconomic landscape, and how it perpetuated the image that San Francisco is just a place that happy people can come to enjoy, rather than a place that is being systematically dismantled for longtime residents who cannot compete against the steep, dramatic changes and social injustices.

Ricky knows fnnch is merely a symptom and not the singular cause of gentrification. He told me that he doesn’t blame one person for all of San Francisco’s problems. “He didn’t invent gentrification,” Ricky acknowledges. “But he most publicly represents what it’s about.” In targeting fnnch’s art in the open, Ricky hopes to bring more awareness to a conversation around these bigger social topics.

As the city has become increasingly appealing to transplants who want to bask in the city’s vibrant artistic and cultural aesthetics, it is simultaneously overshadowing other community members who have helped make it the destination it is today. The city has undeniably changed and embraced a new population and aesthetic and, in doing so, has pushed away the grassroots presence that has for so long sustained and nurtured what Ricky would say is a more “authentic” representation of the scene. Instead of elevating a space for original and emerging local artists to thrive, outside voices and identities have seemingly received the spotlight, while neglecting, underrepresenting, and perhaps exploiting homegrown talent. Ricky isn’t cool with that.

Is Ricky wrong in encouraging viewers to call out how the profitable actions of well-intentioned outsiders can fuel the root causes of socioeconomic disparities for longtime residents?

According to a National Community Reinvestment Coalition study released in June, San Francisco’s neighborhoods are the fastest-gentrifying areas in the entire country. Although fnnch isn’t the one single-handedly driving this upheaval, Ricky Rat believes artists like him are the “poster boys” for these changes, since their artwork and wheat-paste posters can be seen proliferating in redeveloped neighborhoods, while the local population decreases at historic rates. Is anyone’s art commenting on that?

“I like art that speaks on real issues or teaches something, that challenges me to think about things. Like, I want to see the police defunded on a larger scale. That’s what the Bay Area has always been about. I try to get people talking about issues and the local culture. But his stuff just doesn’t do that for me, to be honest,” Ricky says.

In contrast, fnnch has openly stated he doesn’t want to be political in his art. In a recent interview with Haute Living, he said “Something that is truly political is divisive, and I want it to be additive. So, if half the people who see the art are already going to be on the defensive, then my intention is ruined.” But is it a privilege to be able to choose to avoid divisive politics? And how does that choice reflect the reality of the city and what local residents are feeling and experiencing when they are evicted or priced out? Maybe fnnch doesn’t have to be political, and that’s okay, but should we then expect other artists who were born and raised here to be fine with his silence?

“I see myself as a cartoonist and not a street artist,” Ricky admits. “I just hope what I’m doing can maybe inspire other locals to get out and share their own voices. I want to provoke some thought and emotion and not just put up pictures of the same bear for five years in a row.”

At its core, this is about who gets to enjoy making art in a changing San Francisco — and who gets to take selfies in front of that art — while considering the deeper implications of this transaction. It’s 2020, and we are living in a moment as a society where we are questioning the systems and behaviors we have comfortably accepted and normalized for so long. No one is safe from the critical scrutiny of change and accountability, even if it’s an aesthetically sweet honey bear that brings joy to many — because even that same bear could be a factor that indirectly contributes to larger social realities in unintended ways, whether it wants to comment on it or not.

For the record, I don’t have anything against fnnch. In our short email exchanges, he was cordial and seems like a well-intentioned artist who has paved a path with his work and benefited greatly from it in his career. But is Ricky wrong in encouraging viewers to call out how the profitable actions of well-intentioned outsiders can fuel the root causes of socioeconomic disparities for longtime residents?

These are rhetorical questions. Still, it’s worth considering how something as innocuous as a spray-painted honey bear could symbolize our region’s growing capitalistic tendencies at the expense of our most vulnerable residents, and how those tendencies can lead to the displacement and erasure of many, even when unintended.

When it comes down to it, the numbers don’t lie: Neighborhoods in San Francisco are being lost, while others are comfortably reaping the artistic and financial benefits. Whether we blame one artist or actually work to create solutions, this problem needs to be addressed. So, why don’t we agree that this isn’t about two artists vying for your attention; it’s about one city vying to preserve its soul and legacy and about the voices who are fighting to keep that struggle visible.