This article is part of SF Throwbacks, a feature series that tells historic stories of San Francisco to teach us all more about our city’s past. It’s also an excerpt from Alec Scott’s book, Oldest San Francisco — with some edits and additions from The Bold Italic.

City Lights is commonly cited as not just San Francisco’s, but the United States’ first all-paperback bookstore.

On a routine walk from his Mission Street studio to his home in North Beach, Lawrence Ferlinghetti had a meet-cute that would change the landscape of American literature. It was on Columbus Avenue that he crossed paths with Peter Martin, the editor of a culture magazine named after Charlie Chaplin’s iconic film, City Lights.

Peter Martin, the son of a renowned anarchist, was venturing into the world of book publishing with plans to sell and promote literature through his new “Pocket Books” series. As Ferlinghetti introduced himself, Martin immediately recognized him as the person who had sent in the Jacques Prévert translations. This small meeting would soon sprout into a revolutionary idea, as Ferlinghetti would later write: “It was Peter Martin’s brilliant idea to have the first all-paperbound bookstore in the country.”

Paperbacks were mainly pulpy, bodice-rippers before the midcentury, sold in spinners at drugstore and bus stations. But across the Atlantic, Penguin was starting to release great literature in soft covers, and American publishers were starting to follow suit. With an investment of $500 each, the pair soon set up shop in a part of this odd triangular building, with unusually large windows, taking the name of Martin’s magazine.

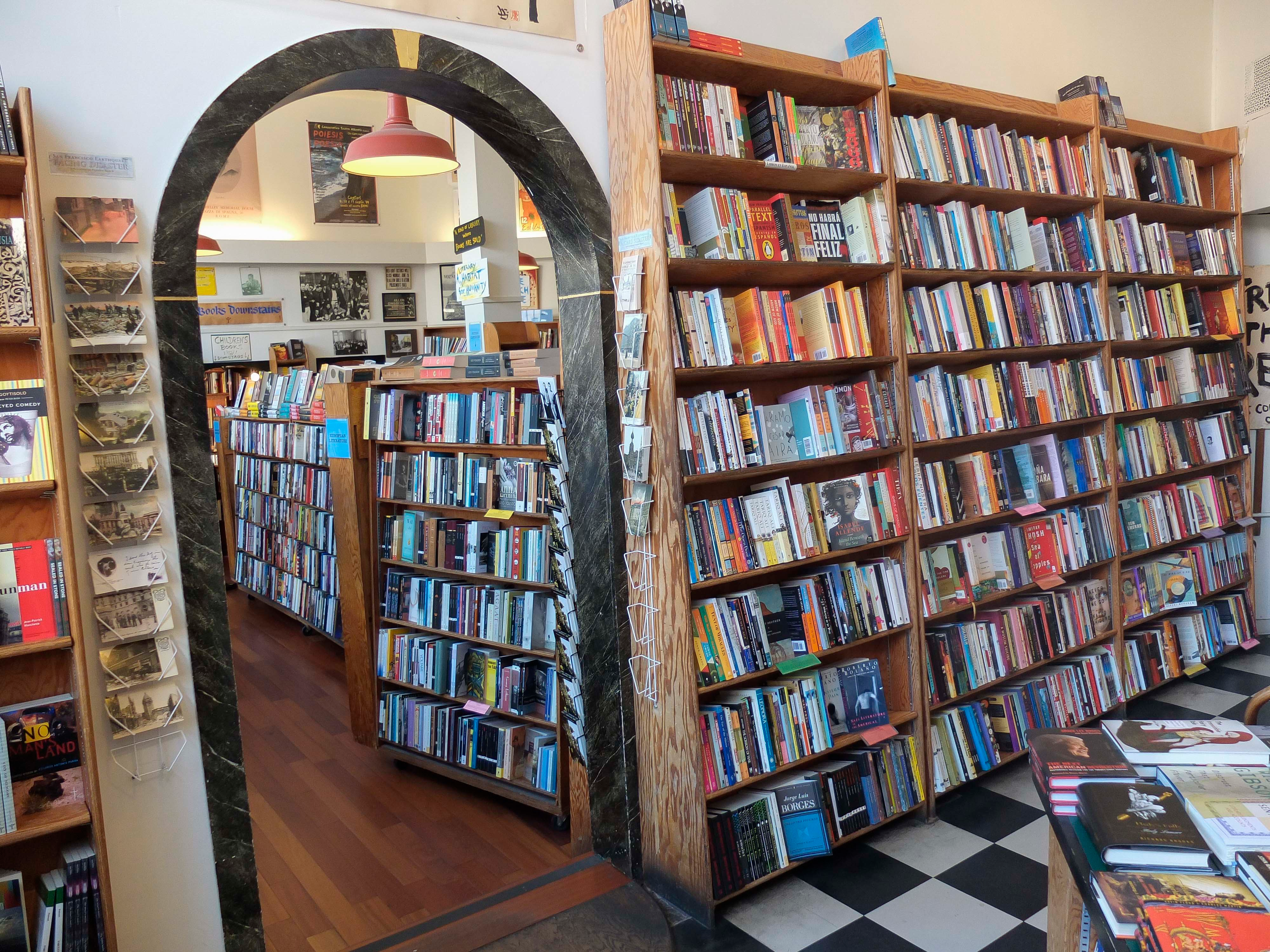

It’s somehow right that the pair’s first exchange related to a French author, and that the shop was located in a building named for two French brothers, Émile and Jean Artigues. French-ness was in City Lights’ DNA, from the kiosks of used books out front that could be closed at night (like those on the Parisian quays of the Seine), to its love of avant-garde art movements (there’s a Surrealism shelf here), to the leftism in its mix (non-fiction downstairs is filed on shelves labeled Muckraking, Class War, and Stolen Continents).

Like Shakespeare & Co., the bookstore started in Paris by a friend of Ferlinghetti’s, City Lights has become a global mecca for readers, a hang-out spot where you can read all day, with no staff throat-clearing nearby.

I made a pilgrimage here on my first trip to San Francisco in 1987, drawn by its association with Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, published in 1955, and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. I bought both, reading the latter on my own cross-country road trip with the San Francisco friend I came to visit. In college, we’d read about the obscenity trial launched against Howl and Ferlinghetti’s spirited defense of its “starving, hysterical, naked” message.

There were still envelopes addressed to itinerant readers and writers on the way down to the basement, reminders that a Christian fundamentalist sect once occupied these premises — “I am the Door” and “Remember Lot’s Wife” were painted on its subterranean walls. Gone, in the building’s bowels, was the fabric dragon used in Chinatown’s New Year’s parade, that Ferlinghetti found stored here when he punched through some plywood at the back of the shop and descended.

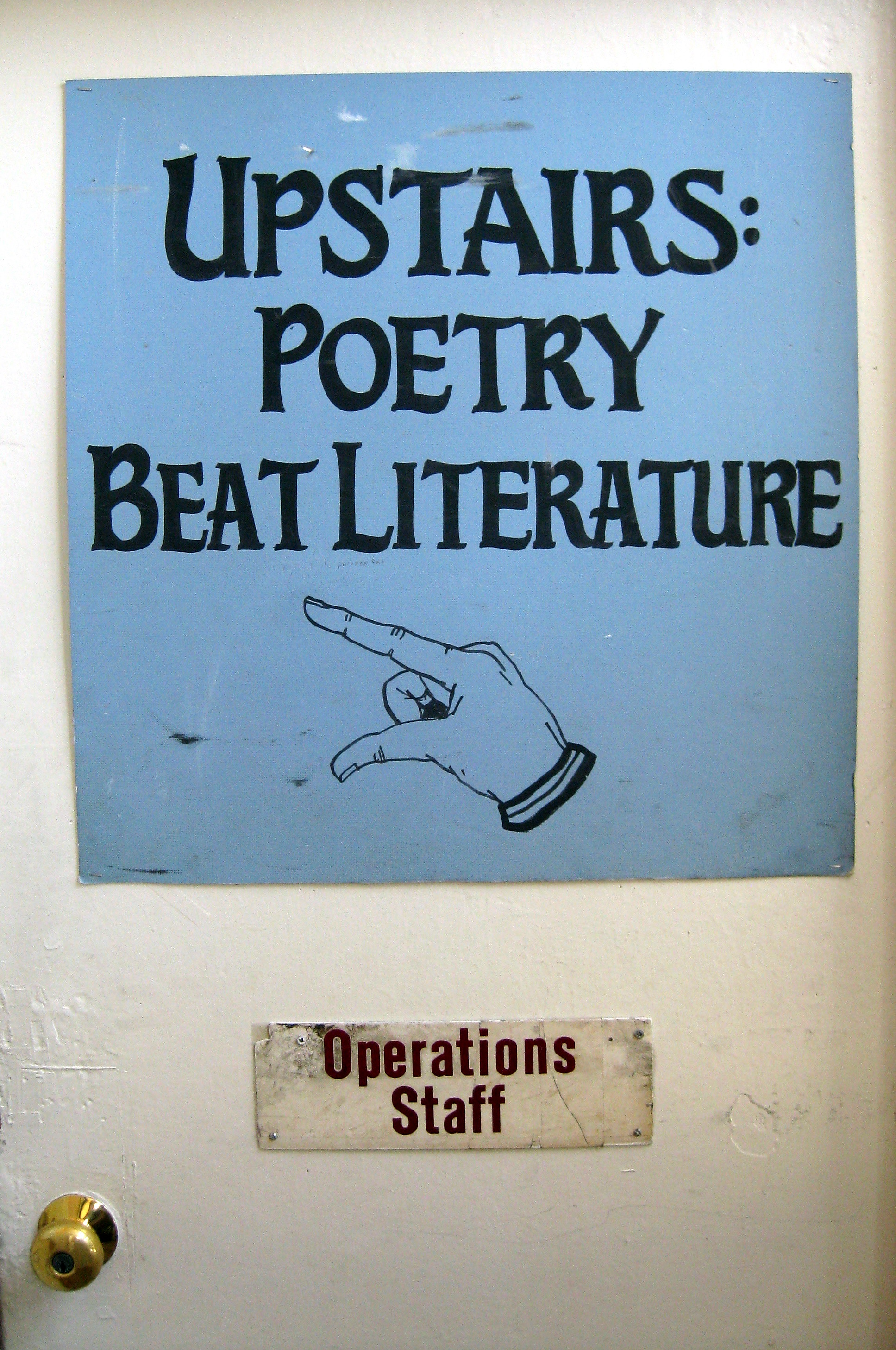

On three stories were books to blow one’s mind — Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the U.S., Armistead Maupin’s early Tales of the City, Denise Levertov’s 1957 poetry volume Here and Now, less celebrated than Ginsberg’s work, but equally vivid. By then, Martin had long returned to New York, and the store had begun carrying hardbacks. It was tidy on its black-and-white tiles, an author reading upstairs less unruly than the legendary ones I’d read about.

But there was still something here — There is still something here. To riff on the title of the first book of poetry it published, Ferlinghetti’s Pictures of a Gone World, here are the remains of a noble world, one celebrating assorted artists and seers and the gifts they bring to this fallen place.

Part of the second floor is still devoted to Martin’s vision, publishing. The small but reputable house produces literature in translation, poetry (in the format made famous by Howl), memoir, and political non-fiction. The shop has changed over the years — it’s had to. “When COVID came, it jumpstarted a redesign of our website,” says staffer Stacey Lewis. “It’s not the same as being here in the store, but we needed it to help people access the books we think are important.” There’s now a Latinx reading shelf, a room devoted to Third-World Fiction.

Luckily, Ferlinghetti and longtime store staffer Nancy Peters were able to buy the building in 2000 as rents in tech-era San Francisco began to spike. “Without that, it’d have been a struggle,” says Lewis, before speaking briefly of what a challenge it can be for their approximately 20 staffers to afford to live here.

No longer can many young, aspiring poet-painters cover the rent on a crash-pad in North Beach and a studio on Mission Street. At the grand age of 101, Ferlinghetti died in February of 2021, leaving behind a threefold legacy: the shop, the publishing house, and his defense of literature’s prerogatives to turn on and offend.

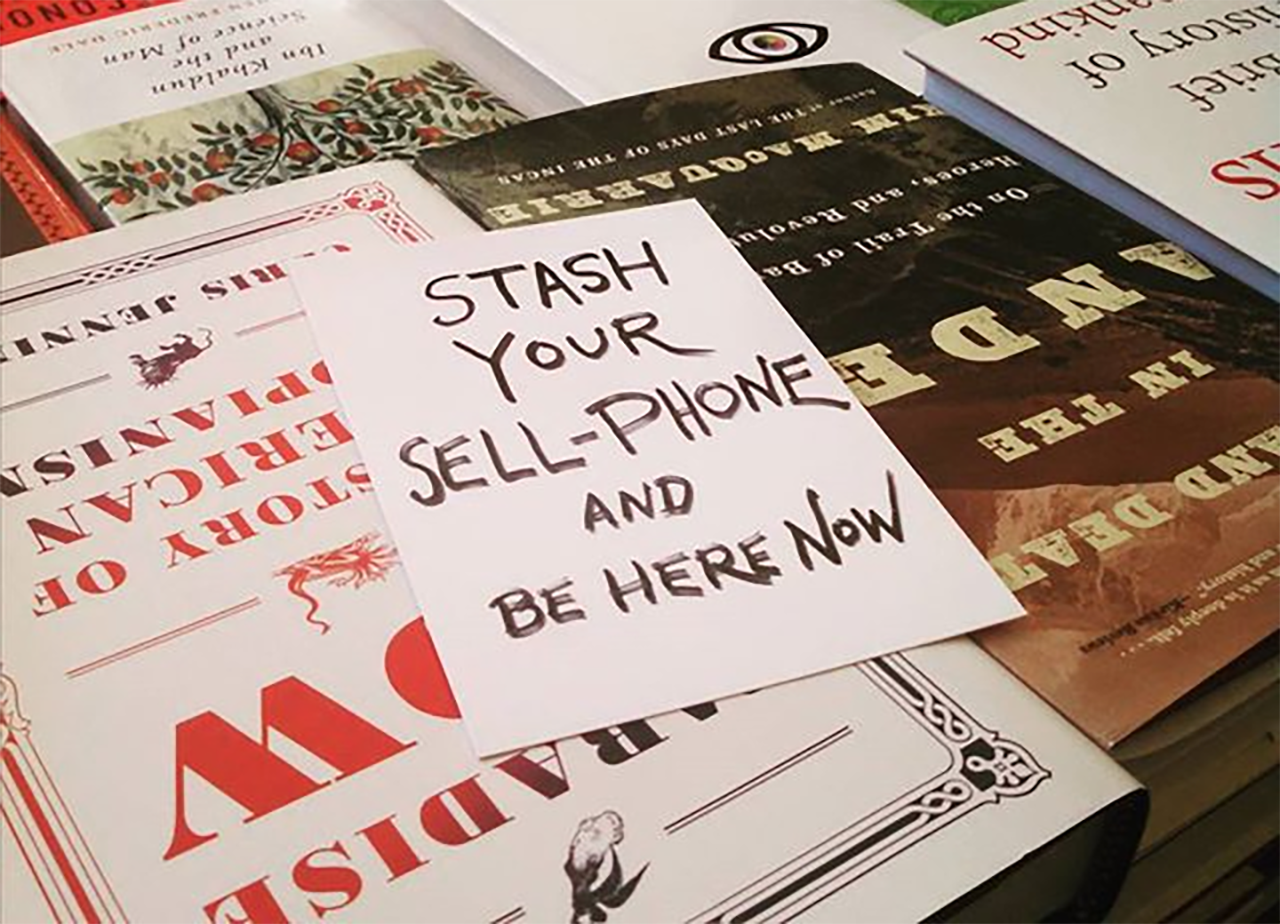

To rising generations, he has addressed a hand-lettered sign that still hangs in the shop: “Stash your sell-phone and be here now.”

Alec Scott is an award-winning journalist, with features in The New York Times, Guardian, Smithsonian Magazine, Los Angeles Times and Sunset.

Learn more about Oldest San Francisco, his latest book with stories of the institutions that helped make San Francisco the place it is today.

The Bold Italic is a non-profit media organization, and we publish first-person perspectives about San Francisco and the Bay Area. Donate to us today.