The long-awaited San Francisco Transbay Transit Center is finally open. And like its neighboring Salesforce Tower, it’s a bold and sweeping vision of the “new San Francisco.”

As someone who works in architecture and has lived in the Bay Area for most of his life, I’ve followed this project’s development closely. Though I currently live in Boston, I consider SF my home and am increasingly concerned about the city’s changing cultural and architectural landscape. These concerns come into focus with the Transbay Transit Center and its most popular attraction—a 5.5-acre rooftop garden named Salesforce Park.

I’ve repeatedly heard Salesforce Park called the “High Line of the West Coast.”

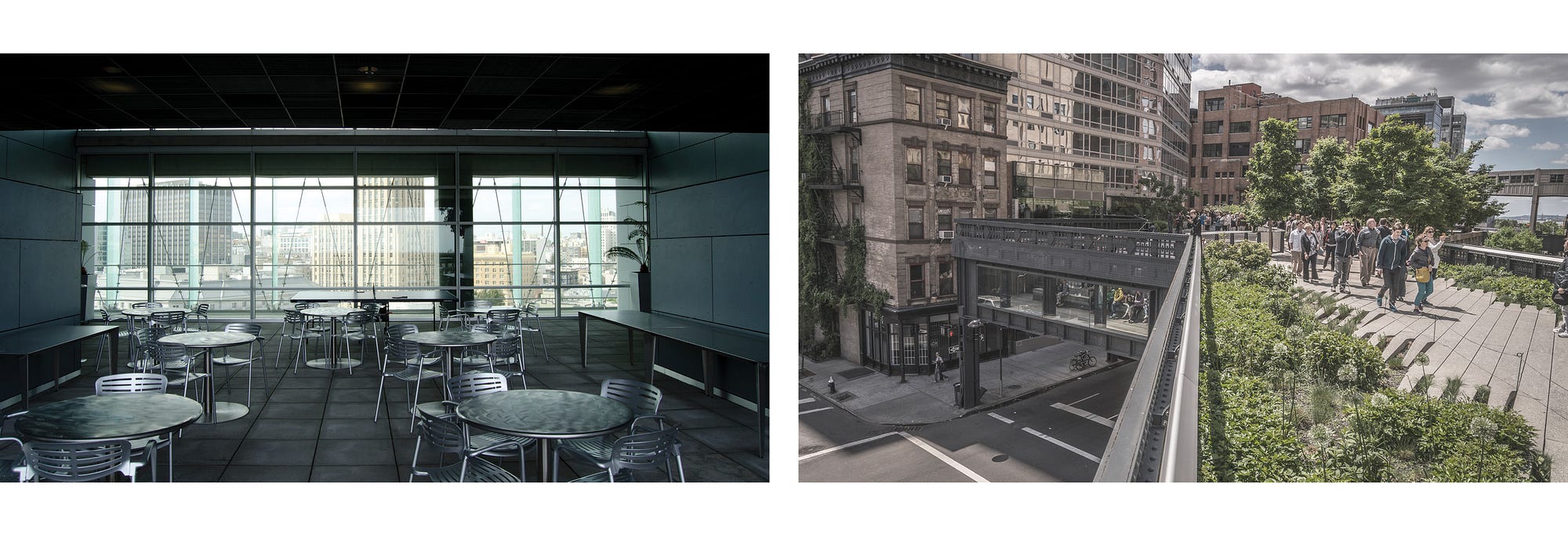

Of course, the Transbay Transit Center is first and foremost a transportation hub, which, when finished, will connect 11 major transit systems, including BART, Greyhound, Muni and the potential future SF-to-LA high-speed rail. However, the park—with its sprawling lawns, skyline views, water features and lush gardens — is the part of the project getting the bulk of the attention.

Over the past few weeks, glossy pictures and high-res aerial photos have appeared in nearly every major national outlet. Because of this hype, I’ve repeatedly heard Salesforce Park called the “High Line of the West Coast” — in the press, in coffee-shop conversations and among family and friends.

The comparison is deeply frustrating. The two parks — namely, the way they integrate into their respective cities—couldn’t be more different.

Regardless of its future popularity and success, Salesforce Park is a missed opportunity in the urban integration of old and new San Francisco.

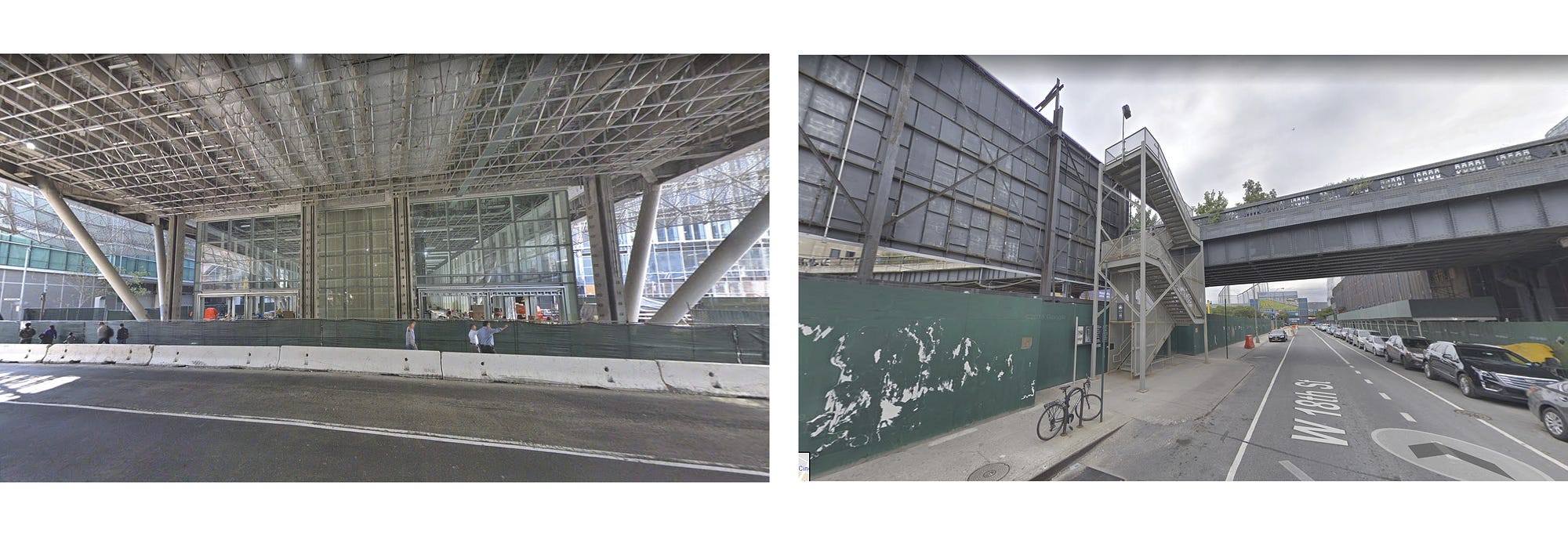

The High Line—a 1.5-mile-long public park built on a repurposed elevated rail line—is an urban element that fully integrates into its existing urban setting and weave pieces of the city together.Salesforce Park, on the other hand, is a walled-off green space in the sky that’s all too symbolic of SF’s contemporary development mindset—one that values isolation and exclusion over inclusion and integration.

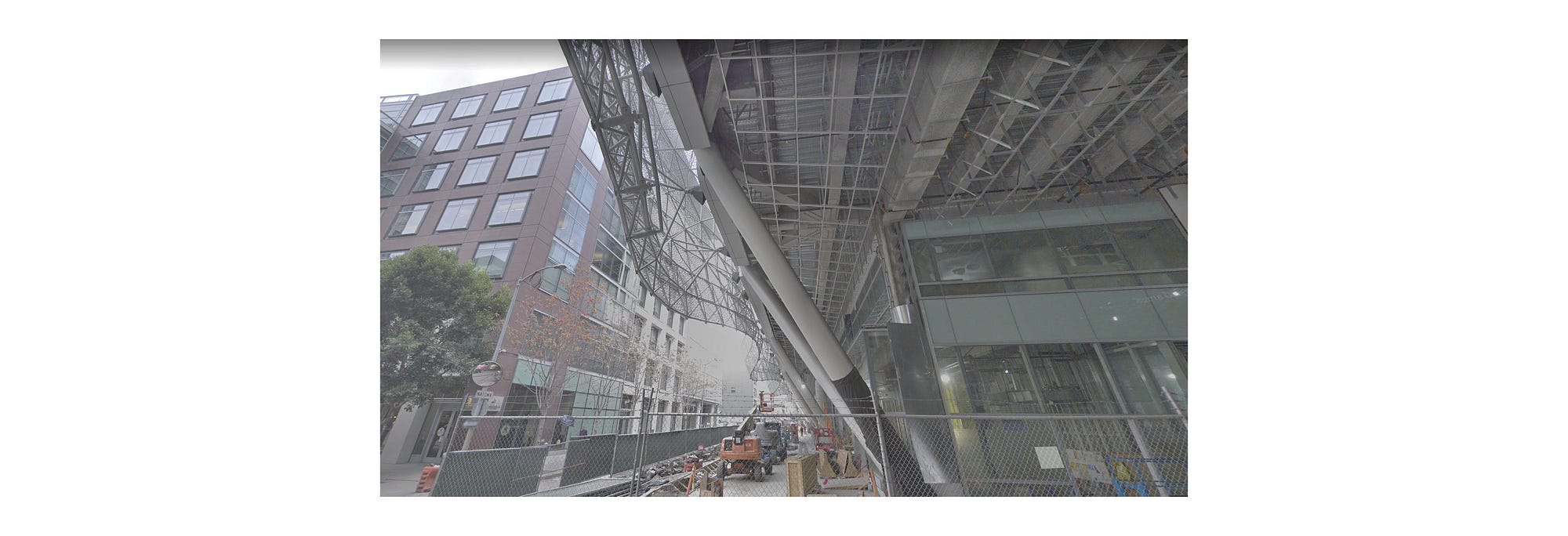

Regardless of its future popularity and success, Salesforce Park is a missed opportunity in the urban integration of old and new San Francisco. Its design is one that proudly celebrates its difference from the rest of the city and refuses to engage with the old—it’s a declaration of something shiny, new and different. Rather than a proposal for a growing and changing city, the Transbay Transit Center is a proposal for an entirely new city.

To better explain my reasoning, let’s take a closer look at the fundamental architectural differences between Salesforce Park and the High Line.

Access

For Salesforce Park, aside from the gimmicky 20-person cable tramway system (which still appears to be inoperable), there is no way to access the public park except through the Transit Center itself. The High Line, however, has multiple access points from the streets and sidewalks of Manhattan. I realize that the Transbay Transit Center is primarily a transit station, but when we consider access to both parks, one is a clear extension of the existing street and the other a displacement.

Organization

The High Line is an elevated walkway that channels people through Manhattan and helps them avoid congestion. It’s an example of a street in the sky — a concept popularized in the 1950s that envisioned social and civic engagement occurring in the air, unimpeded by the rigid street-block grid. Salesforce Park acts as a focal point where people can gather but never just pass through it. It may become a popular destination, but without a proper network, it’s also entirely possible it might turn into a desolate urban zone similar to the many privately owned public open spaces in San Francisco, or the tragically underutilized Kaiser Center Roof Garden in Oakland.

Relationship to Surroundings

The High Line is dynamically engaged with its urban elements, influencing and being influenced by spaces like the HL23 condominiums at 515 West 23rd Street as well as the amphitheater-style observation deck at 10th Avenue and West 17th Street.

The Transbay Transit Center doesn’t engage with its surrounding urban environment. In fact, the design of the façade even seems to create a type of architectural buffer zone between the building and its neighbors.

Given the terminal’s isolation and independence, I can’t help but recall many of the urban-renewal projects of the 1950s and 1960s, where demolition and replacement were favored over integration. In fact, there are only two apparent instances where the Transit Center does appear to architecturally engage with the city, albeit in a relatively minor way: the bus ramp, which connects the building to an on-ramp for the Bay Bridge, and the lobby of Salesforce Tower, which stretches to meet the park but only with a thin platform bridging the two.

I only wish that when we choose to use $6 billion on public infrastructure, we get the most out of its civic use.

It’s no secret that San Francisco—and most American cities in general—are becoming increasingly privatized and commodified. The commons is quickly disappearing. And so it’s worth noting that a piece of civic work at the scale of the Transbay Transit Center is quite incredible. That a large majority of San Francisco’s residents supported the development of such a project and were willing to shell out the cash for public infrastructure is a massive feat. I only wish that when we choose to use $6 billion on public infrastructure, we get the most out of its civic use.

I want to be completely clear: my critique of Salesforce Park lies in its comparison to the High Line and the park’s architectural relationship (or lack thereof) with the city, not the design of the park itself. In other words, my criticism lies in the Transit Center’s architectural and urban design agenda, and not in the landscape architecture itself. I’m certainly rooting for the park’s popularity and success, and hope that it becomes a well-loved part of the city.

If the objective were to serve as a symbol for the city, why didn’t it attempt to better connect the city and its citizens?

I also understand that Salesforce Park was not necessarily built to be “San Francisco’s High Line,” but perhaps it should have been. Both Salesforce Park and the High line are developments of public space by public entities, but only one is successful at integrating into its surroundings and celebrating the city’s existing culture. Of course, the High Line came pre-embedded into the city of New York, and one might attribute the success of the park to its already engaged infrastructure. Yet this certainly does not preclude entirely new architecture and new construction from having the same ambitions. The Transbay Transit Center was as close as it comes to a blank-slate urban-design opportunity. So why couldn’t this project have had similar ambitions in engaging with its immediate surroundings, especially given its public ownership? Why couldn’t it have taken a cue from the High Line and been a driver for urban growth in a more lively and dynamic way? If the objective were to serve as a symbol for the city, why didn’t it attempt to better connect the city and its citizens?

I recognize San Francisco’s need to adapt to the times, but it must do so in a manner that doesn’t completely erase the old in its search for something new. It must tap into the existing city fabric rather than completely disregard it. The High Line openly embraces and engages New York City — its past, present and future. I only wish the Transbay Transit Center did the same for San Francisco.

Hey! The Bold Italic recently launched a podcast, This Is Your Life in Silicon Valley. Check out the full season or listen to the episode below featuring Jessica Alter, founder of Tech for Campaigns. More coming soon, so stay tuned!