By Tienlon Ho

“Dad, you’re Chinese,” I said, producing a malformed packet with two beaks. “What do you think makes a good dumpling?”

With a blur of motion, he conjured a wonton so perfect, I could hear it chirp, and then looked at me, puzzled. “Well,” he said, “it all depends on what you mean by ‘dumpling’.”

There are at least as many different dumplings in Chinese cuisine as there are sandwich varieties in the States, and just as with the Philly cheesesteak or the New Orleans po’ boy, which is best depends entirely on where you happen to be.

Chinese food is so tied to place that the particular spring from which you draw water to cook is considered an ingredient. Among the varieties of dumplings readily found in San Francisco, there are jiao zi, what many of us think of when picturing the proverbial dumpling; originating in the northern part of China, wrapped in wheat dough and shaped like fat, silver ingots. When fried, they become guo tie, what most of us know as potstickers.

Wontons also originated in the north but are the explorer Zheng He of dumplings, having first crossed China and then found its way all over the globe.

From Shanghai came xiao long bao, round dumplings shaped like lotus seed pods, cooked in bamboo steamers, and bursting with a rich broth upon first bite. And then in the south, there are the many varieties comprising dim sum that are wrapped in everything from rice, wheat, or bean doughs to assorted leaves. In China, these are just a start.

So, when forced to make some generalizations, my dad with his decades of making and eating dumplings offered some wisdom. First off, you can judge a dumpling by its cover. The texture and thickness of the pi — the skin — has to be just right and always delicate. When it comes to jiao zi and xiao long bao, “the pi has to have jiao tou,” dad says, the sort of texture where “you have to chew a few times — but not too many — to work through it.” When it comes to Chinese food, English can be a blunt tool, so let’s just say that jiao tou falls somewhere in the chewiness spectrum between al dente and gummy.

I discovered just what jiao tou is at the Shanghai Dumpling King in the Outer Richmond — or rather, my four-year-old niece did. The shop is loud and cramped, with sticky tables, but people endure long waits for a taste of the signature “Hung Zhou” crab and pork steamed dumplings (eight for $8.95).

The Dumpling King crew makes nearly a thousand daily, using the clever old method of stuffing the dough with aspic (gelatinized crab and pork goodness) that melts into a mouth-watering broth when the dumplings are steamed. The shop also kneads its own dough, letting it rise multiple times to give it just the right firmness, so that it holds everything together without being leathery. After a month in Shanghai eating the real thing, my little niece had a hankering for soup dumplings that no joint in the city had fixed. It was at the Dumpling King that she finally peeled each of her dumplings, setting the meaty centers aside, and chewed contentedly on the skins with a glazed expression. I ate them more conventionally — set in spoon, cool, bite and drain like a vampire, top with ginger and black vinegar, and then chew.

A good dumpling also knows that true beauty comes from within. The xian’r — the filling — should be flavorful, tender, and moist, but not fall apart, dad says. In my experience, the most ornate dumplings — those shaped with hundreds of tiny folds into multi-tiered fruit baskets or Mickey Mouse — tend to fall short. But I found a dumpling with both form and substance at Kingdom of Dumpling in the Outer Sunset. Kingdom of Dumpling makes 24 different types of jiao zi (about $6 for a plate of 13), with the tastiest involving lamb or some combination of pork, shrimp, napa cabbage, chives, and mushrooms. As I sank my teeth into a portly dumpling, it was clear the secret of filling is as much about the quality of the raw ingredients as it is about pounding the hell out of those raw ingredients.

After overdoing it with three rounds, I drove a few blocks to Kingdom of Dumpling’s factory arm for a chance to see how the perfect filling is born. The factory doesn’t offer an official tour, but I got an informal one peering into the back kitchen, which is tucked behind four rows of massive freezers. There, a gaggle of ladies in white smocks wielded cleavers the size of toddlers in each hand as they pounded pork cutlets at the pace of jackhammers. With precision no food processor could mimic, they slowly turned the cutlets into a soft, peach paste. They did the same to the vegetables, adding those to the paste. Then a tiny woman with a long pair of chopsticks slowly stirred stock into the filling until it disappeared like magic. It was enough to persuade me to buy a few bags of frozen dumplings for another day ($4.50 to $6.99 for bags of 24).

One other thing about good dumplings is that they always get their math right. “Dough and filling have to come together in just the right ratios,” dad says. If not, they fall apart during cooking, or worse, you end up with a blob of dough clinging to a dry wad of meat.

I discovered what he meant by perfect proportions at Yank Sing in SoMa, which serves up an awesome array of dim sum dumplings piled high in steaming, rolling carts and made by clearly obsessive hands. Yank Sing is the place I hate to love. It defies the Native Eater Rule, that unspoken understanding that the authenticity of the food is equal to the number of customers who appear to have grown up eating it. The glassy, gilded décor has all the charm of a tourist trap in a Hong Kong mall. The bill always comes out to twice as much as any other dim sum joint. But Yank Sing’s perfectly bite-sized dumplings are undeniably delectable. On a recent visit, the warm curry flavors of a savory vegetable dumpling stuffed with crunchy bamboo shoots and gingko ($4.65 for four) were enough to distract me from a cart as it ran over my foot.

On another Sunday morning, when the line of parents in weekend-casual khakis snaked out Yank Sing’s door, I headed to Chinatown in search of the golden dumpling ratio without the wait. I found it at three very different restaurants.

Great Eastern has both the pomp of starched linens and waiters in matching vests and the efficiency of an In-N-Out. The dumplings are made to order rather than carted about, so I ticked off 12 very different dumplings off the menu and settled in with a pot of chrysanthemum tea, expecting a wait. Before I finished my second cup, a cacophony of tinkling plates appeared on the table, bearing everything from peanut-filled zhiu zhou to cilantro shrimp dumplings ($3.30 for four). I gorged on them, animal style.

Just up the hill from Great Eastern are even speedier options, assuming you don’t need a menu and are willing to learn some Cantonese (or at least how to politely gesture toward your favorites).

At Yong Kee, a narrow bakery with no seating, the dozen of us patrons jockeying for attention had a full meal in hand for less than $5 and in less than five minutes ($1.20 for three of most anything on the menu). The menu here hasn’t changed since it opened more than 40 years ago, and so when I asked for one, owner Kwa Wong had to dig under some newspapers for what appeared to be the last of its kind. I took it to write this article, so hopefully Mr. Wong has made more copies since.

At Dol Ho, the regulars treat the cafeteria-like space as their community center, reading the paper and playing chess while downing dumplings and tea. They may be whiling away the hours, but evidently not patiently. When the lady at the counter kept me waiting for my shark fin dumplings ($2 for four) all of three minutes to restock her supply, she apologized profusely. The tantalizing, porcelain-white dumplings lasted about as long on my plate.

After my dad and I cooked up and devoured the wontons, he offered one more dumpling observation. A well-made dumpling is a perfect food. It contains almost all the food groups in one tasty, pretty package. It’s the kind of thing that can bring families together as they sit around for an afternoon, wrapping the few hundred morsels that it takes to make a meal. It’s the sort of perfection that inspires poets.

It was at this point that dad leaned back in his chair and recited a poem that had been thought up by some anonymous foodie, who had been stirred by a bowl of jiao zi long ago:

“Among delicious things, nothing compares to dumplings.

Of comfort, nothing’s better than lying down.”

And with that, my dad went to the living room to do just that. I did the dishes.

Try dim sum at Great Eastern, Dol Ho, Yong Kee in Chinatown, or Yank Sing in SoMa; Shanghai soup dumplings at Shanghai Dumpling King in the Outer Richmond; and jiao zi and guo tie at Kingdom of Dumpling in the Outer Sunset. Kingdom of Dumpling sells frozen bags of dumplings ready for boiling (or boiling and then frying) at its Noriega Street factory.

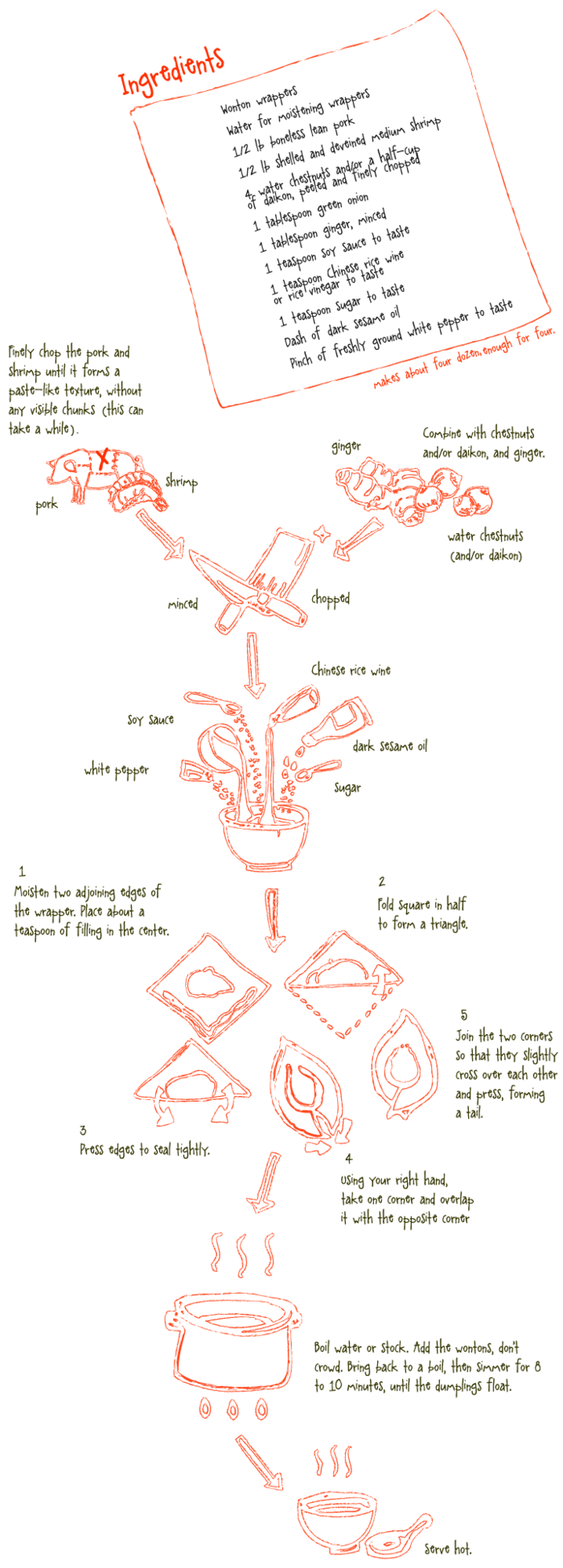

Or try making some at home. Wontons are the easiest to make of the dumpling genre, especially if you buy the wrappers premade.

Design: Caroline Wiryadinata