I never believe anyone who says they don’t like art. What they usually mean is that they don’t like museums. And that I can believe.

Plenty of people have the experience wrecked for them by well-meaning teachers and relatives who insist that culture needs to be appraised and reviewed with the same stoic reverence as an open casket at a wake. People come away from these experiences feeling like they just spent a whole day trying to stifle a sneeze.

Of course, there’s another group: those who adore museums but can’t find either the time or the money to go. And while many San Francisco institutions have at least a few free days a month, it can be tricky to fit them in the calendar or to even get out there for the brief window of time during which they’re open. (I’m looking at you, Japanese Tea Garden! A one-hour window from 9:00 to 10:00 a.m. on a weekday? Would it kill you to block out a few hours on a Sunday?!)

The dilemma for either requires a new approach. If you don’t like traditional galleries or can’t wait for the next free day, why not treat the city of San Francisco as an art gallery in and of itself?

There’s so much great art that’s already free and available to the public at almost any time of day. You just have to know where to look.

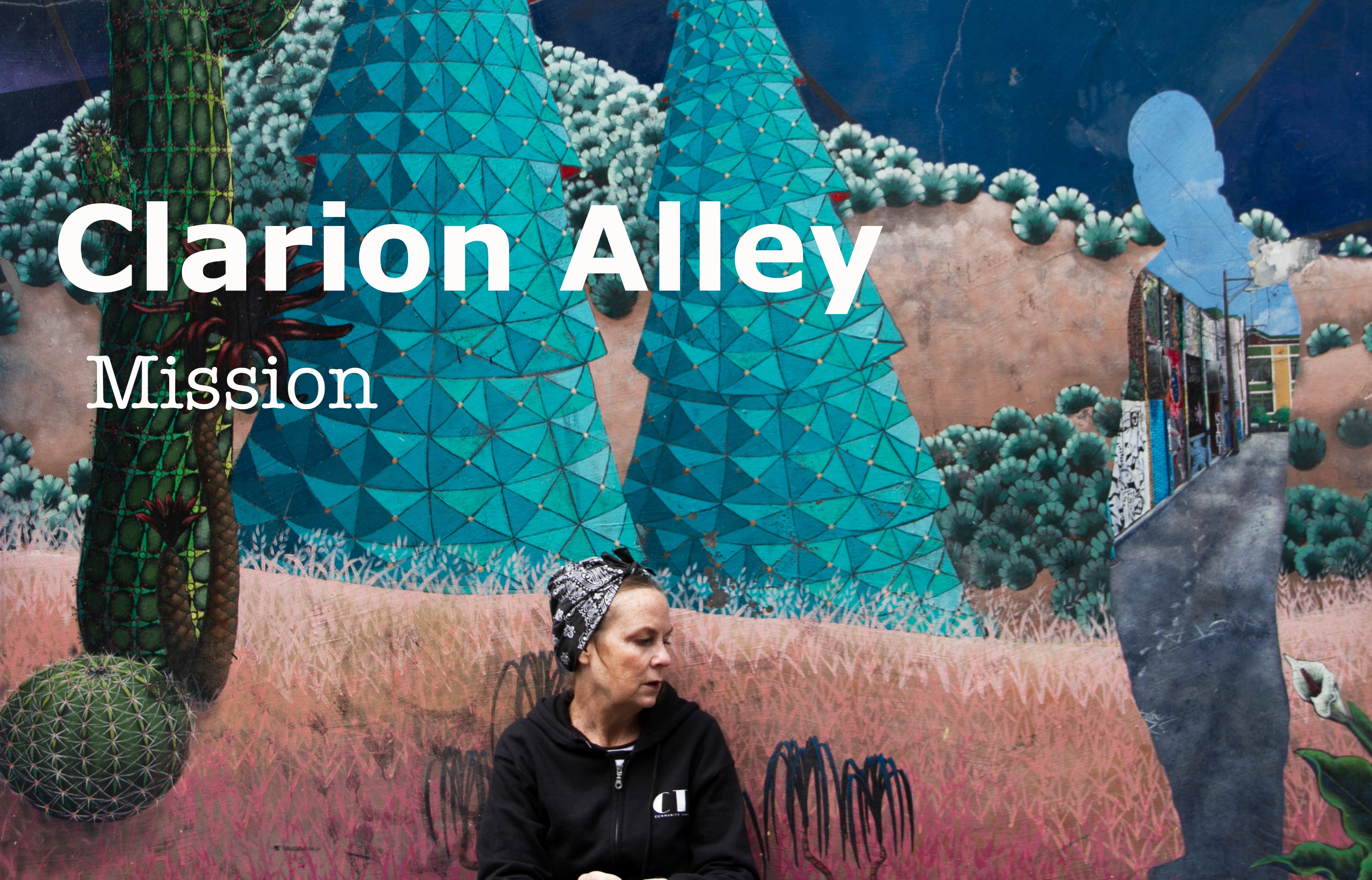

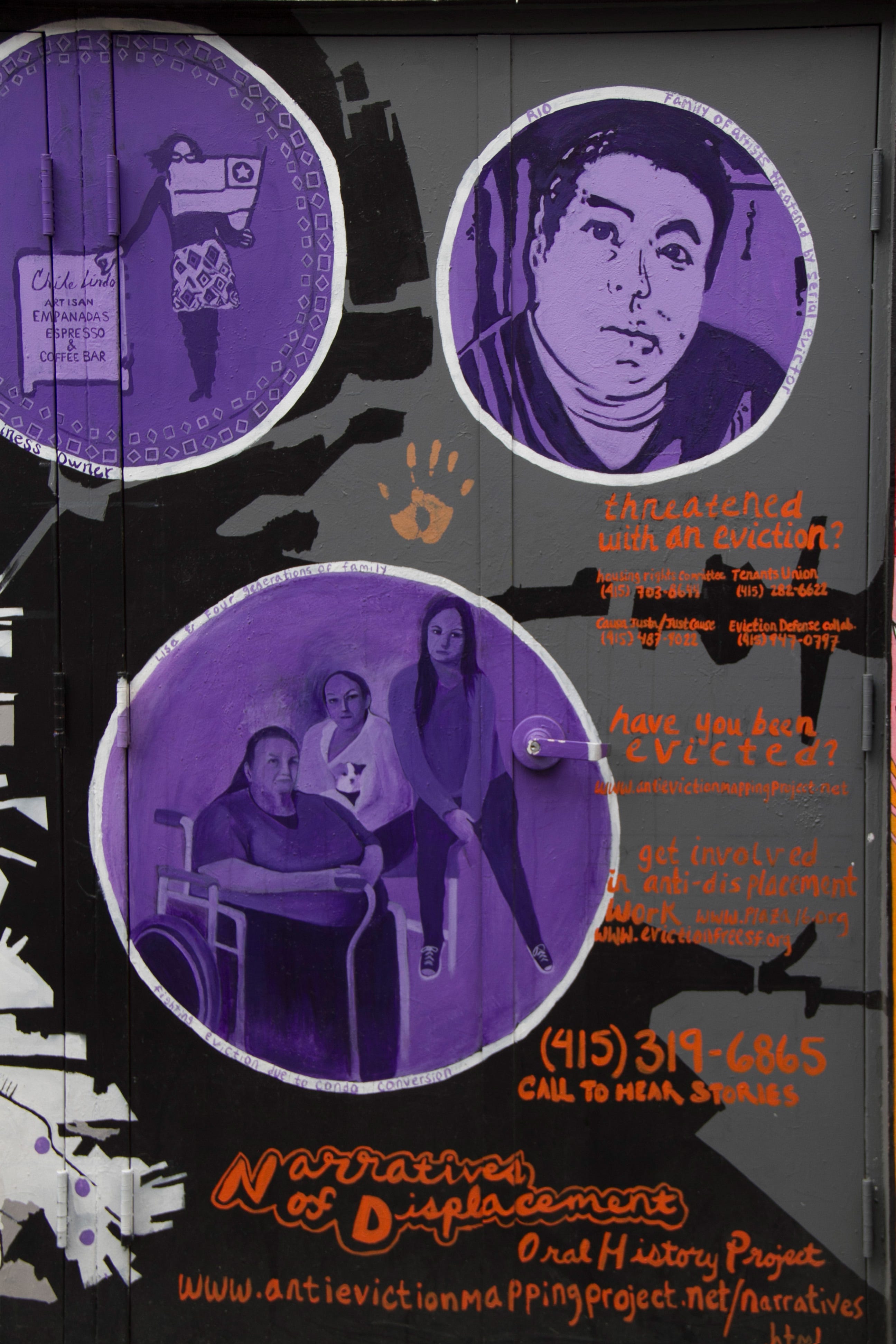

Murals are the Chronicle of street art, and Clarion Alley is its front page. Since its beginning in 1992, the Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP) has supported more than 500 artists — far too many to name and do justice to in a short article. But doing justice and giving voice to the unheard-of have been major themes of the project from the beginning.

The alley runs parallel between 16th and 17th Streets in the inner Mission and connects Mission and Valencia Streets both geographically and metaphorically. Only 560 feet long and 16 feet wide, Clarion encourages intimacy and engagement, and it can be hard to know if the audience is commenting on the art or the other way round. While a few of the murals are on “permanent display,” the majority are always changing as artists respond to new challenges with new ideas. Like the city itself, there’s always something new to see.

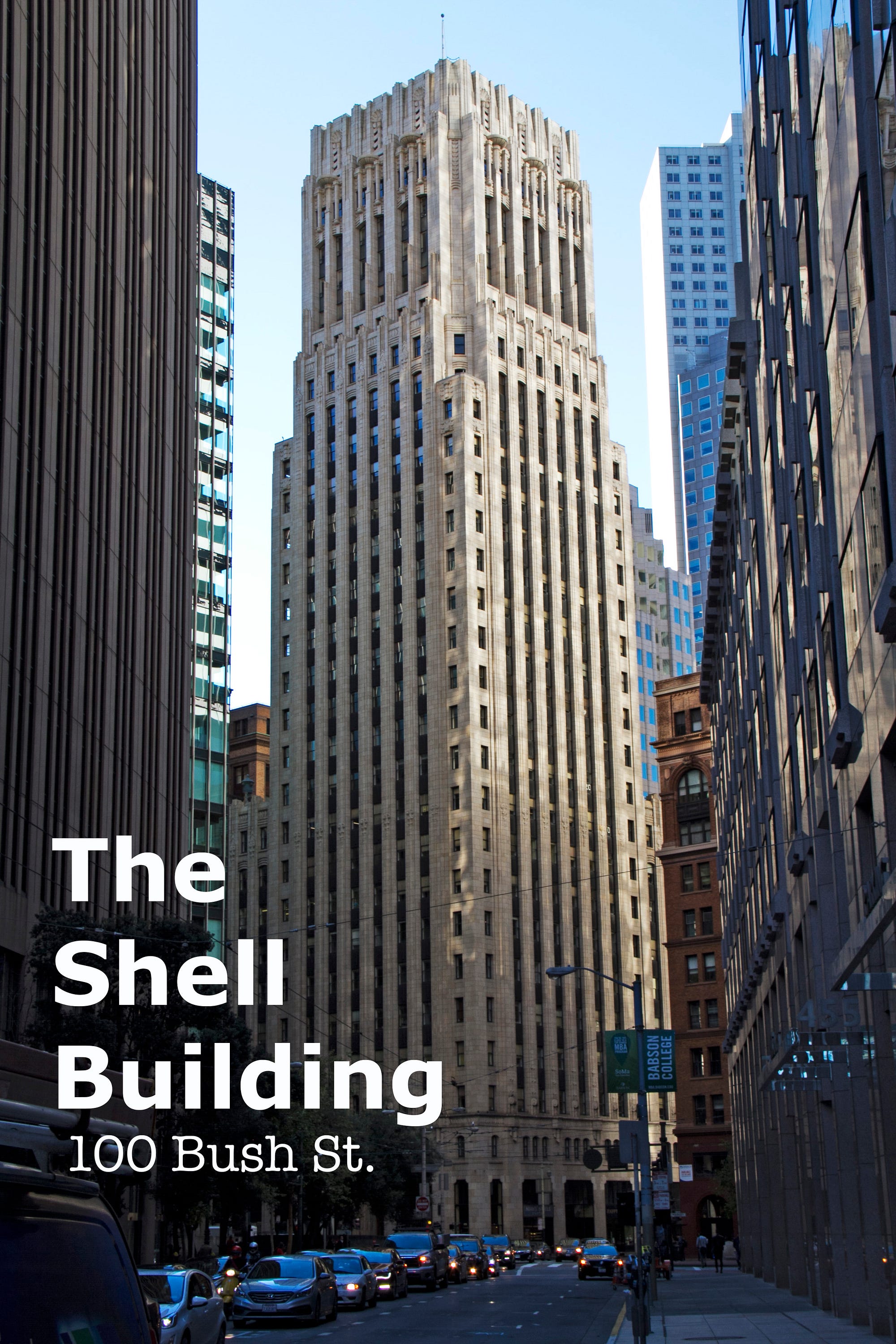

From 1910 to 1940, three architects controlled the shape of San Francisco. The most accomplished was George Kelham (for the other two, keep scrolling). While Kelham wasn’t particularly inventive, his work is reliably classy. It’s got swagger, verve, panache and all those other adjectives that fit with 1930s Art-Deco-meets-Gothic-Revival. Most of Kelham’s work has since been swallowed up in the concrete jungle. But in the hour before sunset, if you look north up 1st Street, you’ll see that the Shell Building glows like a beacon.

Film isn’t dead; it just likes to hang out in a gallery above Market Street. Begun by a collective of San Francisco artists in 1974, SF Camerawork encourages and supports emerging artists and new ideas in photography. SF Camerawork offers classes, portfolio critiques and lectures for a fee, but the gallery is free and open to the public from noon to 6:00 p.m. on Tuesday through Friday, and from noon to 5:00 p.m. on Saturday. Ring the doorbell, and they’ll let you up.

If you can think of a building you love in San Francisco that was built sometime between 1920 and 1950, it probably had something to do with Timothy Pflueger. The Castro Theatre, the Pacific Exchange, the McAllister Building and the Bay Bridge, for which Pflueger championed the long fight to paint the bridge some color — any color — besides the one chosen by the engineers: black. Perhaps because they saw a red bridge? After all, the Golden Gate Bridge had been finished just a few years before.

With his partner, James Miller, Pflueger designed the 450 Sutter Building. From the outside, the building is no eye-catcher. But the inside is an homage to Mayan-themed Art Deco. No elevator was ever more baroque. No parking-garage entrance more ornate.

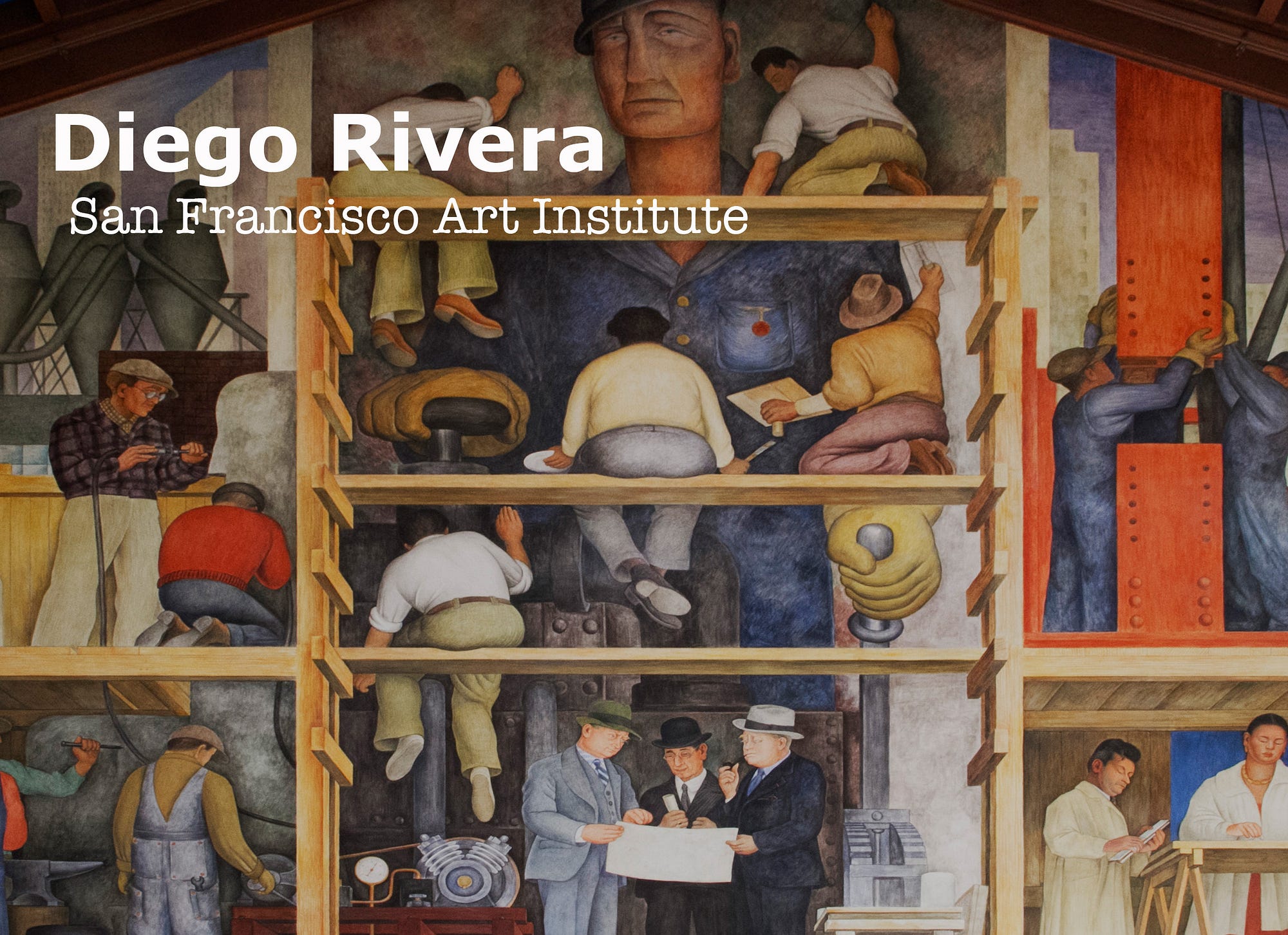

San Francisco actually boasts three Rivera murals (technically, they’re frescos but, you know, tomato/tomural), including the first mural the artist ever completed in the United States. Of the three, the mural at SFAI is probably the easiest to access and is certainly in the most tourist-friendly location. It’s halfway between Fisherman’s Wharf and North Beach, and a short athletic stroll from Coit Tower. Go through the gate at 800 Chestnut Street, then turn left in the courtyard, and, suddenly, you’re inside a gallery the size of a barn.

Rivera is known for his bright colors and for celebrating the working man. Layering the modernization of the city, the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge and the literal building of an everyman, Rivera includes political messages with the process of making a fresco — a kind of painting within a painting. As a sort of signature, Rivera put himself in the work. Although his face isn’t showing, he’s still easy to find (hint: look for the guy holding a paintbrush).

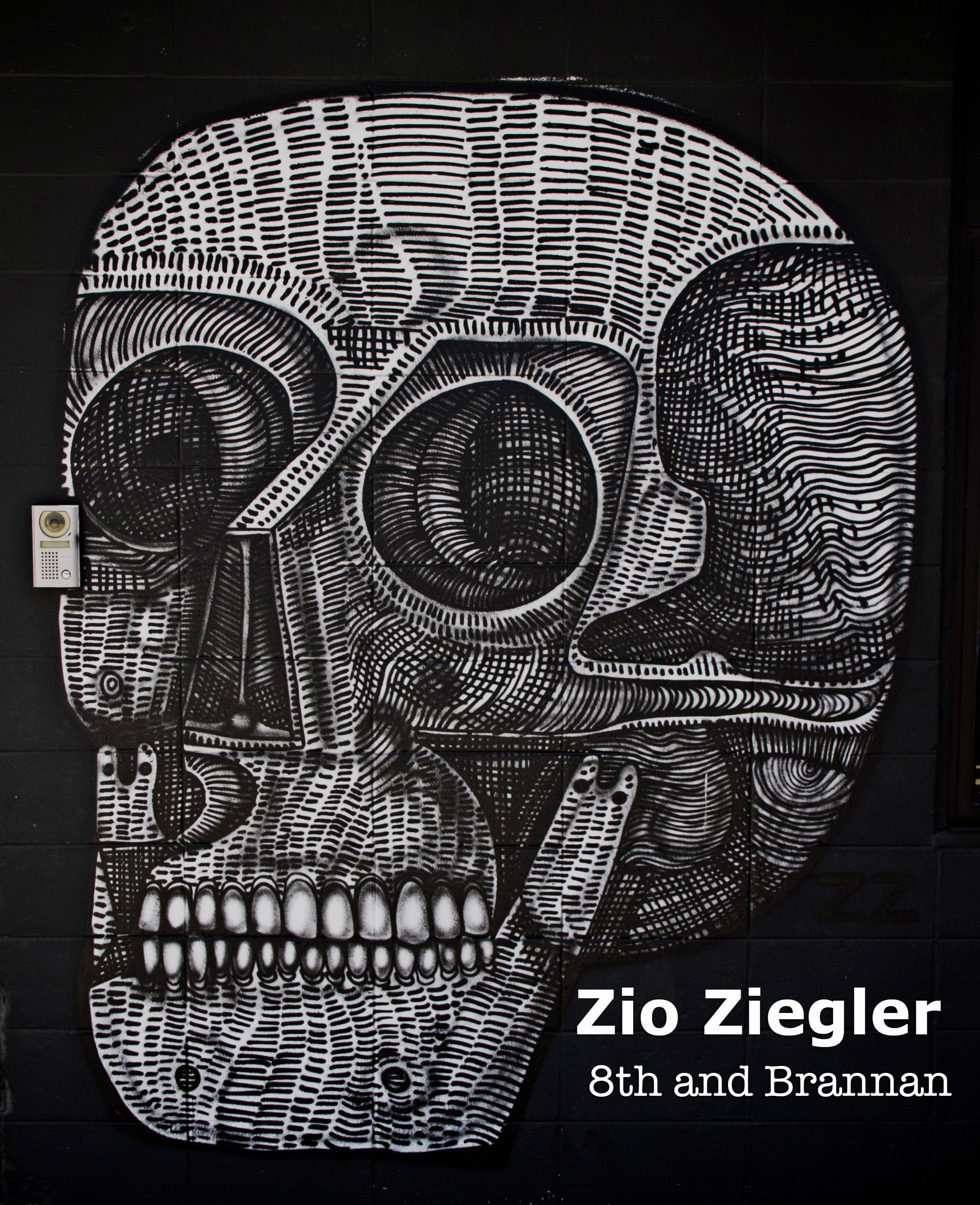

If it wasn’t already obvious, San Francisco has a world-class collection of street art, some by long-dead international artists (see above) and much more by young, active and local ones.

Polymath and street-art wunderkind Zio Ziegler is a muralist, designer, essayist, videographer and documentarian. And although he’s spending more time in his Marin studio these days — or putting work up at tech companies and in European metro stations — you can still find his distinctive street art at several places around SF. Much of his earlier work from his up-and-coming days has since been painted over, but some gems remain. Once you know what to look for, you start noticing his work all around San Francisco. Ziegler’s improvisational style — once seen — can’t be unseen.

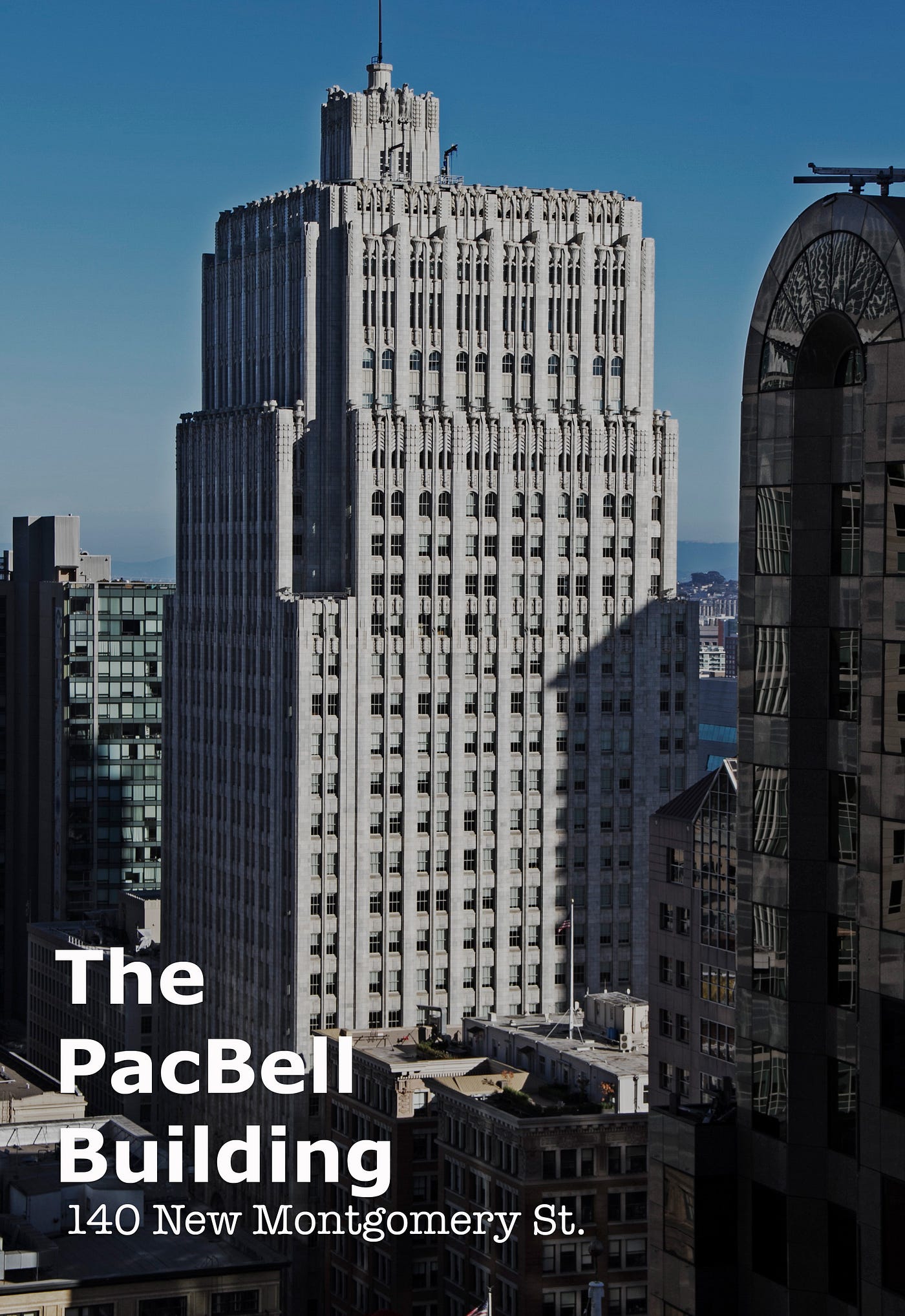

While the Pacific Bell Telephone Company may no longer occupy 140 New Montgomery Street (AT&T sold the building in 2007, and Yelp has been the main tenant since 2013), the PacBell Building is still a treasure of the industrial age. The 26-story terra-cotta wedding cake is another of Miller and Pflueger’s masterpieces, each tier making a Gothic reference to the client. The place practically drips in motifs of telephones and bells. A visiting Winston Churchill made one of the first transatlantic telephone calls here in 1927, and you still half expect the old bulldog to exit one of the lobby elevators as you go in the door. At its final tier, eight stone eagles stare out in the four cardinal directions, because why should Paris hold the monopoly on gargoyles?

Someday I would like someone important — preferably a publicist — to invite me to high tea at the Palace Hotel to discuss optioning the rights to my book in Flemish. And afterward, if there’s still time, I’d like to get into a fistfight with the Prince of Belgium at the Pied Piper Bar & Grill. The restaurant is named for the Maxfield Parrish painting that has hung above the bar since 1909. Parrish was known for images that paid homage to Pre-Raphaelite painters and to stories of myth. Although Parrish lived most of his life in New Hampshire, his paintings show a thorough western influence in their brightly saturated, luminous landscapes.

In the early months of 2013, the century-old painting was removed by the new hotel owners, Kyo-Ya Hotels & Resorts, for restoration. The intentions were far from noble. Deeming the piece too valuable and culturally important to be left on public display, Kyo-Ya really just wanted to spruce it up for auction.

But San Francisco be praised! When the news hit, public outcry raised enough of a stink to get the now-restored painting put back exactly where it had always been.

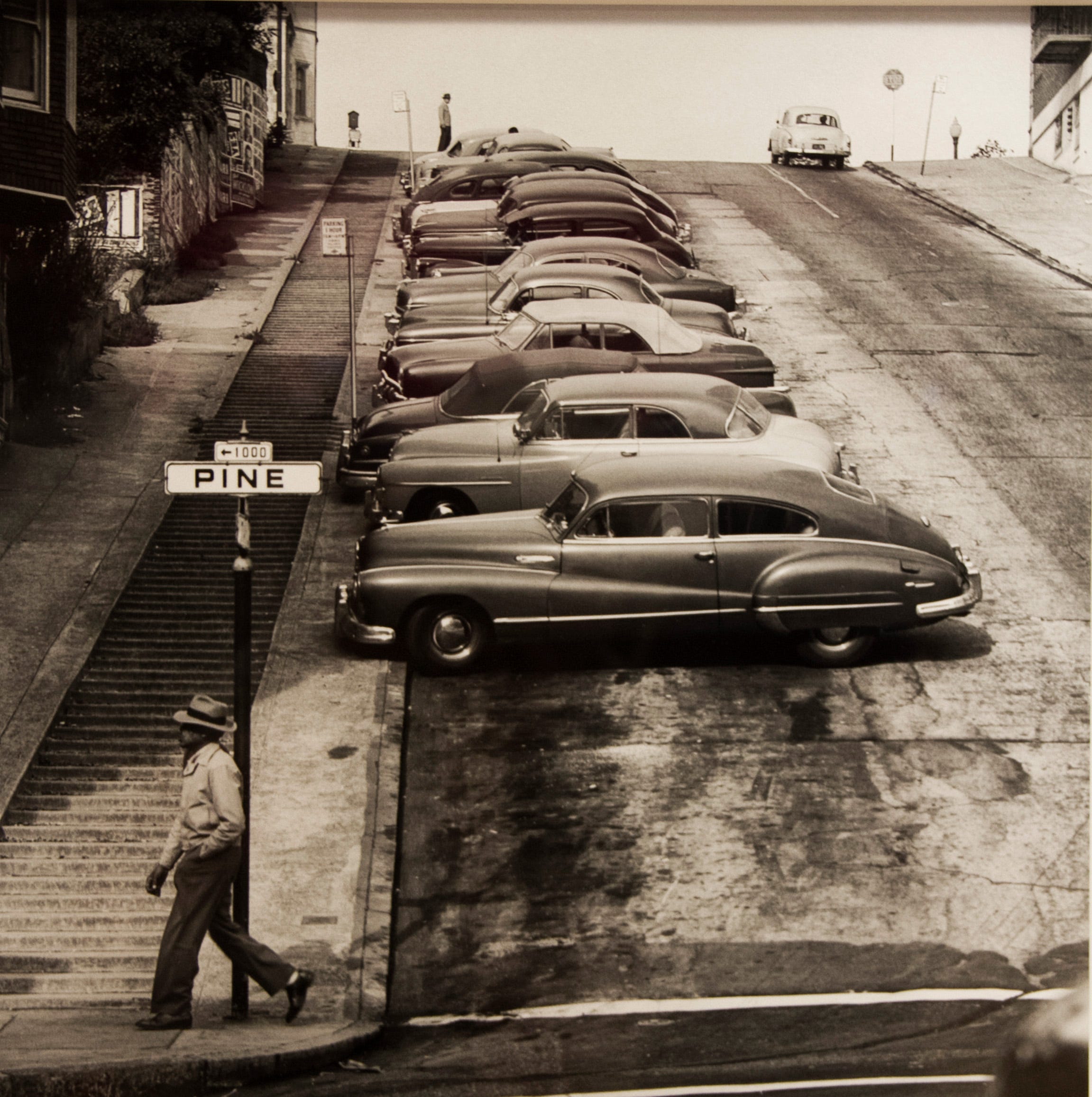

A Leica camera is arguably a work of art in and of itself. But the store also has an excellent gallery that is free and open to the public during business hours. The current exhibition of legendary photographer Fred Lyon is on view now through October 21.

Located across from the Chinatown Gate and next to Café de la Presse, at the edge of the Financial District, the store is an easy walk for a lunch break and a fantastic place to get inspired by photography and camera gear, and to dream of all the easy ways there are to blow a million dollars.

And gallery openings are always an excellent opportunity to see classy ladies in really big glasses.

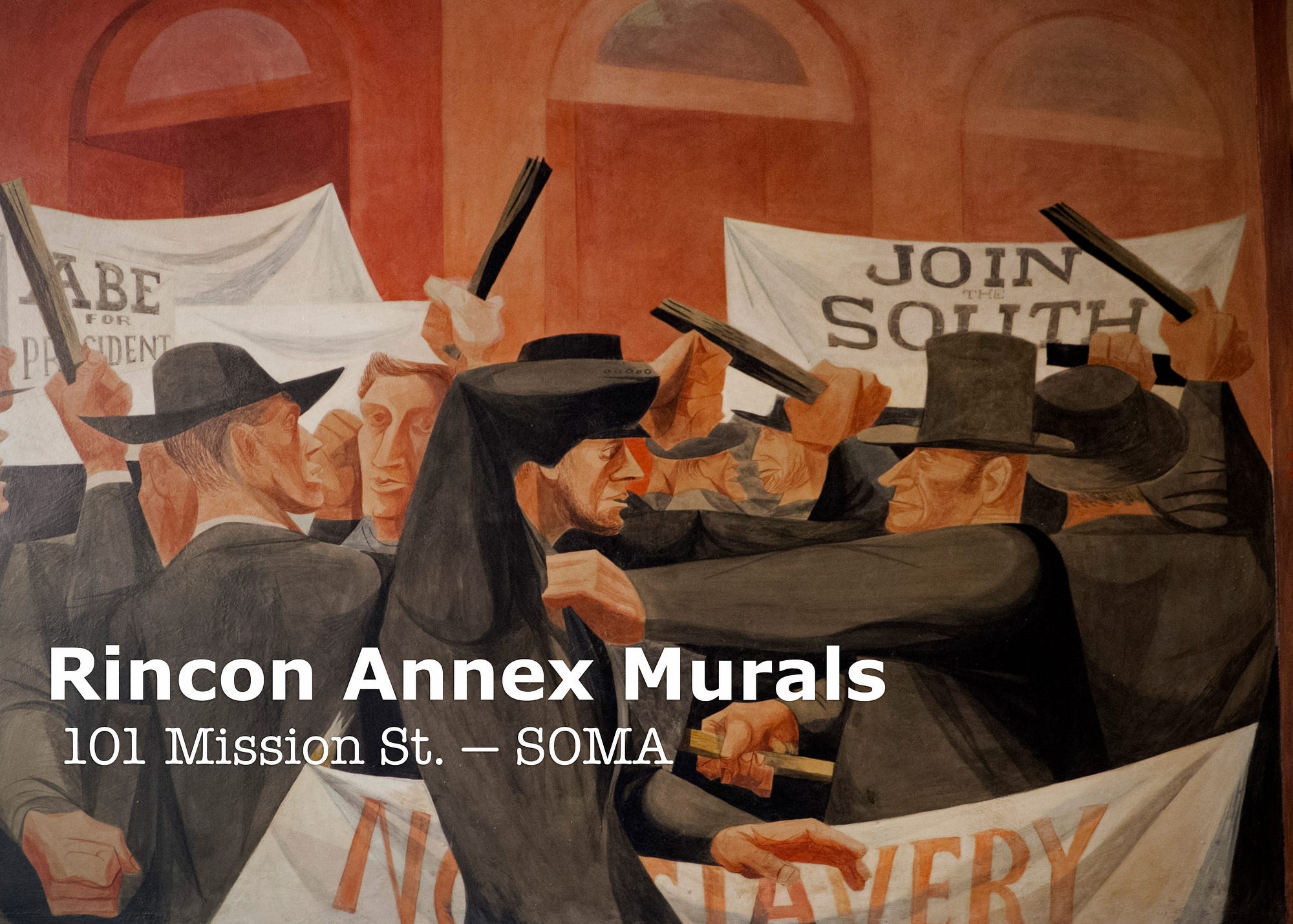

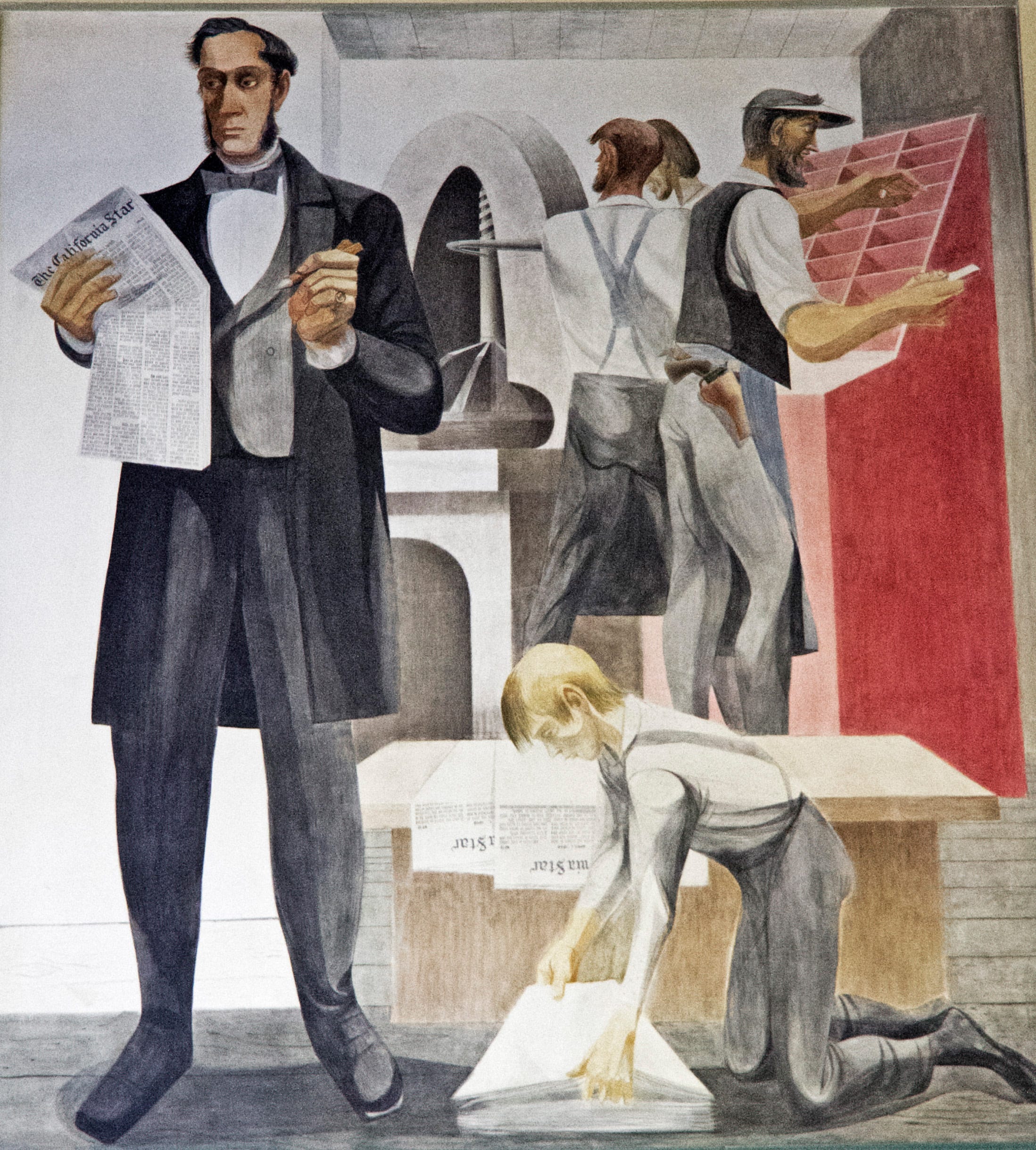

Painted as part of FDR’s Works Progress Administration, the Rincon Annex murals are remarkable for their bullet-point, warts-and-all history of San Francisco. Sure, they show the standard stories of the SF creation myth: the Franciscan fathers, Sir Francis Drake and the gold rush. But they also show the displacement of indigenous peoples, the abuse of Chinese immigrants, the Civil War riots, vigilante committees and the theft of the city from the Alcalde of California back when the state was still part of Mexico.

On a more progressive note, they also show the founding of the city’s first newspaper and numerous portraits of the black and Hispanic steel workers who came to work in the Bayview shipyards and on the Golden Gate Bridge. Like all art, the Annex murals tell you more about the time when they were made than the times they represent. But they’re proof that San Francisco, while a city, has also been a kind of madness contained on three sides by water.

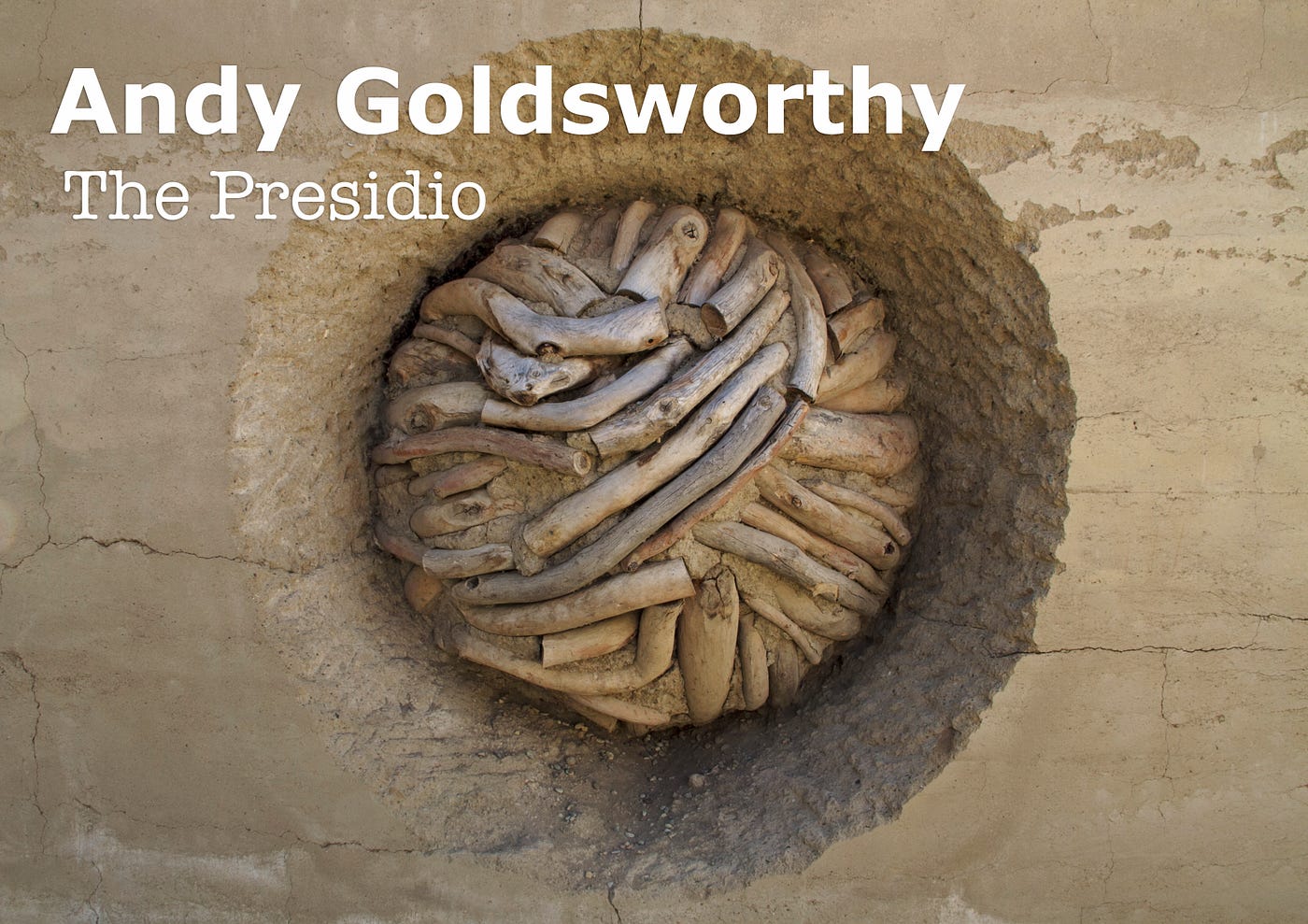

Chances are if you can name only one sculptor of the natural world, it’s Andy Goldsworthy. The British sculptor is known for his intimate attention to nature and for preferring to use only material found on-site and rarely using tools any more complicated than his own hands in the creation of his work.

Though there are several of his pieces around the city, his best are Earth Wall, Spire and Wood Line, all located in the Presidio and within an easy walk of each other. With the exception of Earth Wall , which is located in the Presidio Officers’ Club, all are open to the public 24–7 free of charge.

My suggestion? Phone a friend and pack a picnic for what is probably the easiest way to appear both curious and cultured on a date.

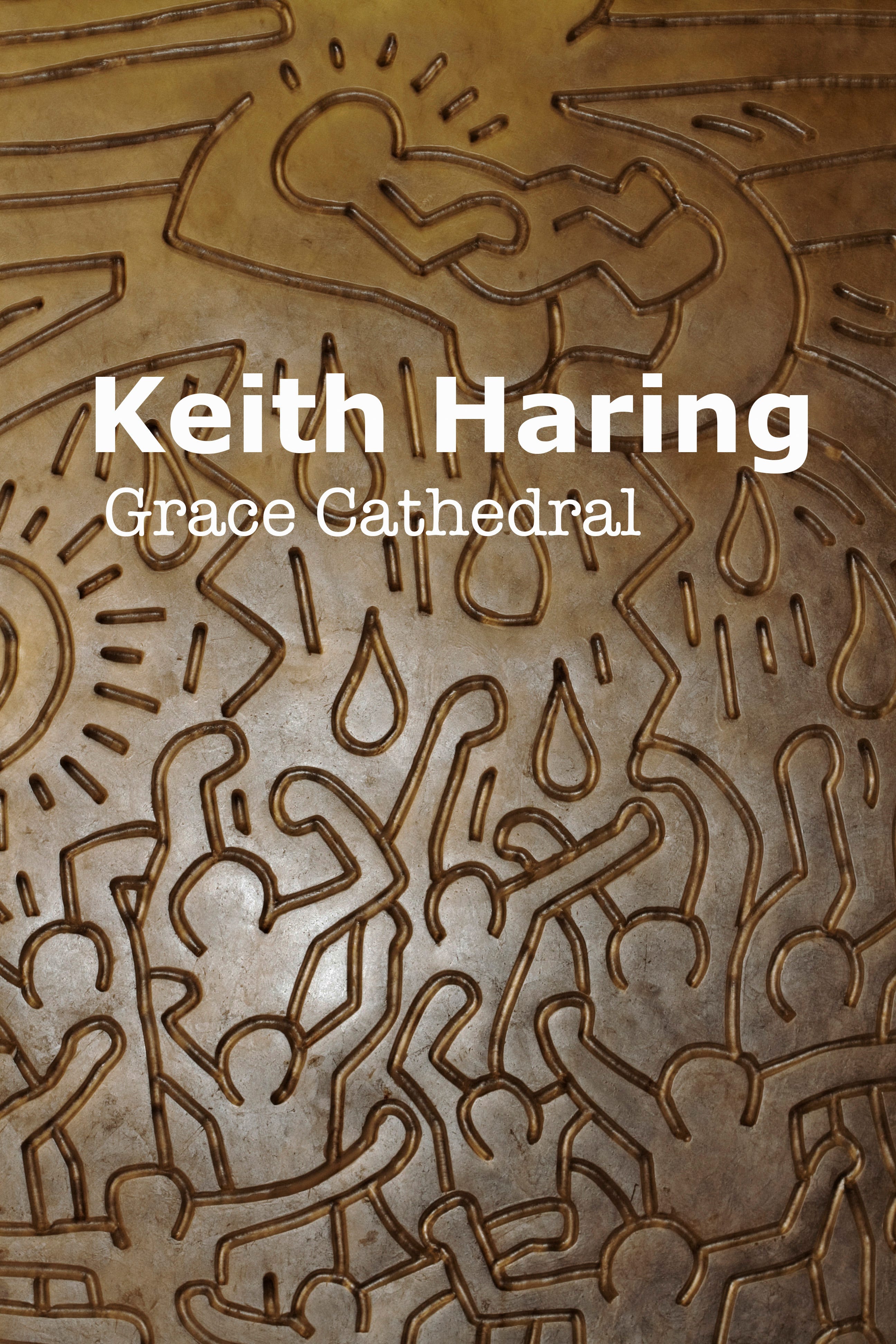

Probably the best lines ever written about Grace Cathedral come from the fictional Michael Tolliver of Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City. Numbers 10 and 11 of the “Valentine’s Resolutions”:

10. I will ease back into religion by attending concerts at Grace Cathedral.

11. I will not cruise at Grace Cathedral.

At the peak of California Street, on top of one of the city’s loveliest of hills, Grace Cathedral has some of the best views and best art in San Francisco. The Keith Haring altarpiece in the Interfaith AIDS Memorial Chapel is one of only three ever made in the artist’s lifetime. And the stained-glass windows by Gabriel Loire of Chartres are a bold, new treatment of traditional Judeo-Christian themes. How many cathedrals are there in the world that show the Holy Family and Albert Einstein? The cathedral also has a public gallery and artist-in-residence program.

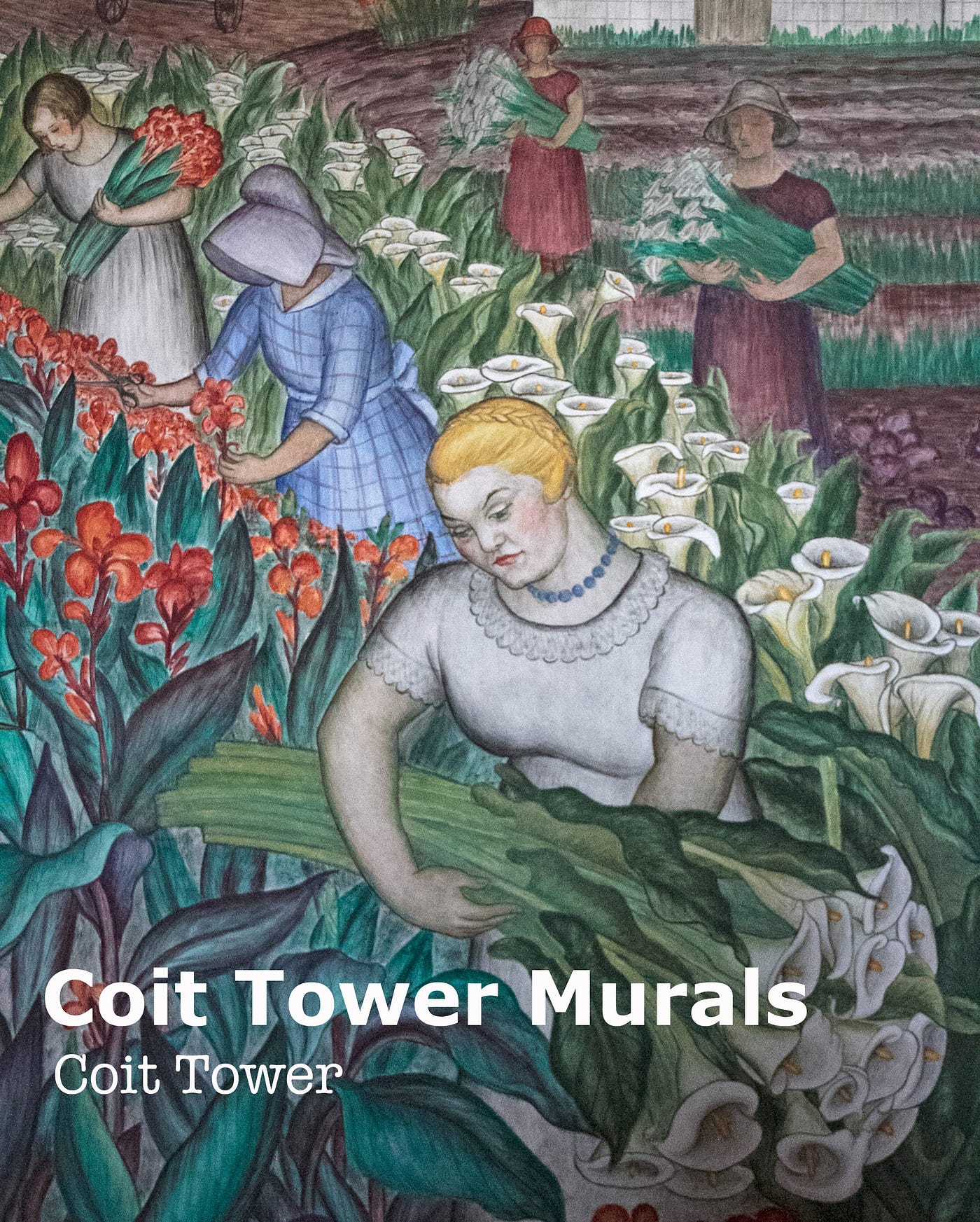

Though often attributed to Diego Rivera, the Coit Tower murals were painted by local artists, professors and students of the nearby San Francisco Art Institute, where Rivera had been in residence. At the time the murals were being painted, Rivera was in New York working on an installation at the Rockefeller Center.

All the same, the artists of the Coit Tower murals paid a good deal of homage to their beloved instructor by including direct references to his work (such as calla lilies), a portrait of the artist and the same political consideration for the working man that Rivera gave in his own painting. And there are also a few dirty jokes and graffiti that the artists placed in each other’s paintings, which makes for a fun Easter-egg hunt if you’re waiting in line for the elevator.

Like in the Rincon Annex murals, one sees the construction of the city, civil unrest among laborers, the founding of unions and the 1934 waterfront strike that shut down West Coast shipping from Seattle to San Francisco. In one corner, academics read newspapers, and at the top, you can just make out the headline for how Rivera was getting on with old Nelson Rockefeller.

While it will cost you to ride the elevator to the top, the first-floor murals are free to the public. And if you let the security guards know that that’s all you’re looking for, they’ll usually even let you cut the line.