This article is part of SF Throwbacks, a feature series that tells the stories behind historic photos of San Francisco and the larger Bay Area in order to learn more about our region’s past.

In 1961, two students named Huey Newton and Bobby Seale met at Merritt College in Oakland. Together, they went on to form the cornerstone of the Black Power movement: the Black Panther Party. As protests calling for justice and an end to police brutality following the murder of George Floyd have erupted across the nation, we wanted to take this opportunity to look back at the history of Black activism in the Bay Area.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

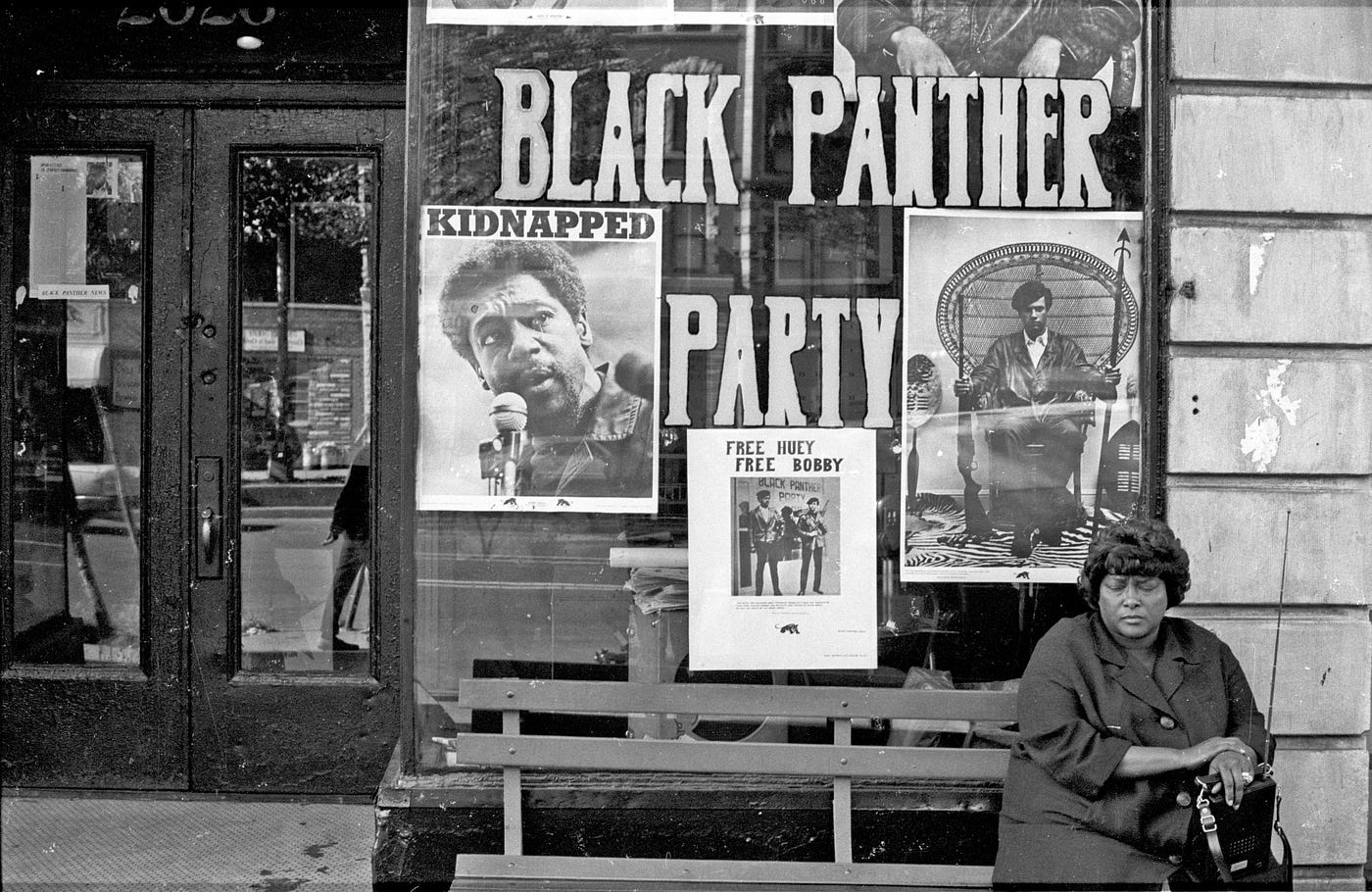

Newton and Seale founded the Black Panther Party in 1966, publishing a Ten-Point Program that called for systemic change and upward mobility for Black and oppressed communities in the forms of employment, housing, health care, an end to incarceration and police brutality, and other reparations. They were inspired to act following the assassination of Malcolm X as well as the murder by police officers of an unarmed 16-year-old named Matthew Johnson in Hunters Point, San Francisco.

The Black Panthers went on to be active until the early 1980’s. Throughout the 60’s and 70’s, they were largely vilified by politicians and the media. Even now, they are often remembered for their defense tactics — like using guns to protect themselves against police violence —over their commitment and significant contribution to mutual aid and community support in the Bay Area.

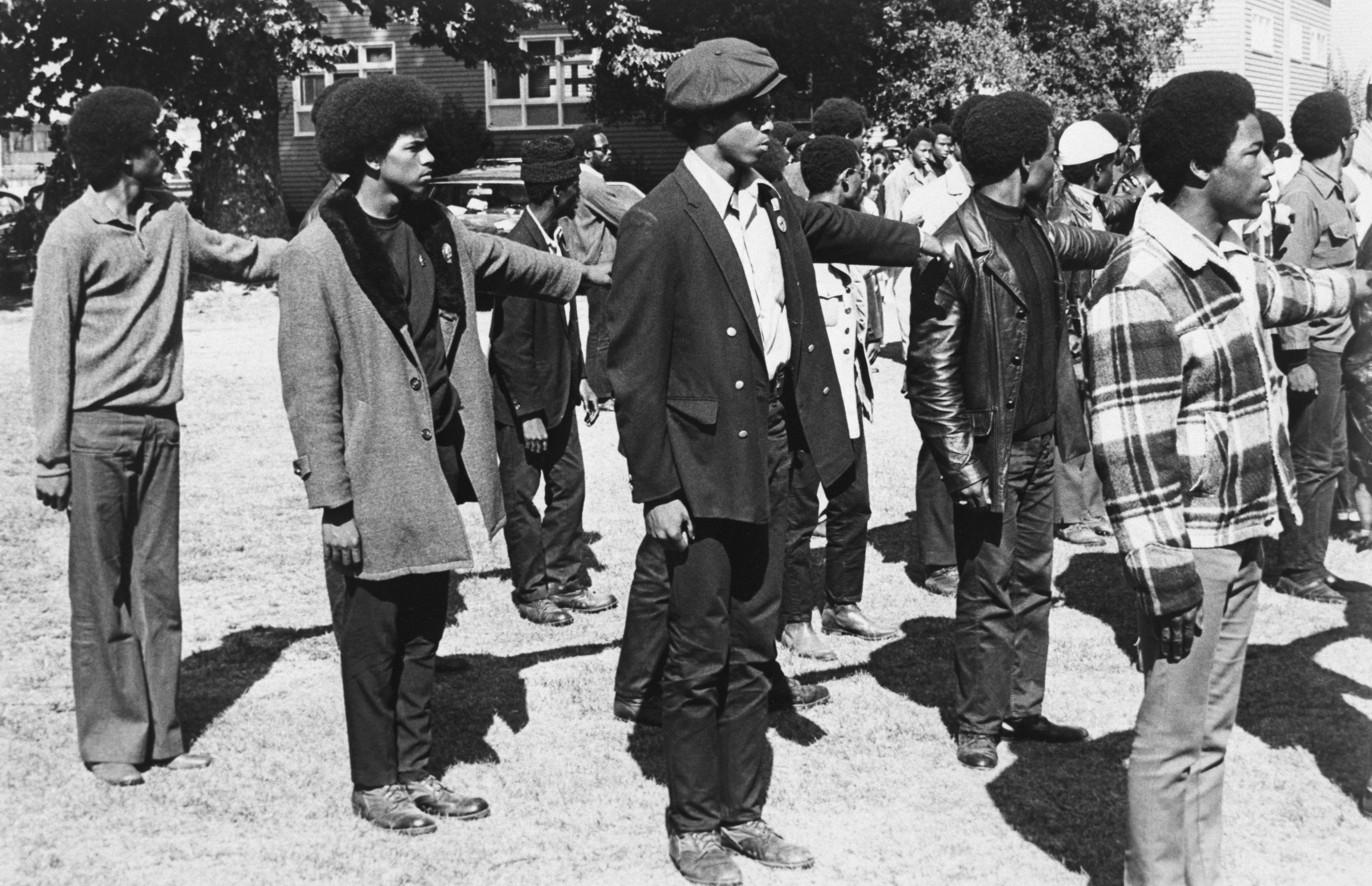

Originally, the goal of the Blank Panthers was focused on ending police brutality in Oakland. But when Newton and Seale met Stokeley Carmichael, they also included black power as part of their platform. At first, they focused on organizing patrols monitoring police activity in predominately Black neighborhoods, and expanded out to organizing rallies and marches, as well as a slew of social programs, including health clinics and serving meals.

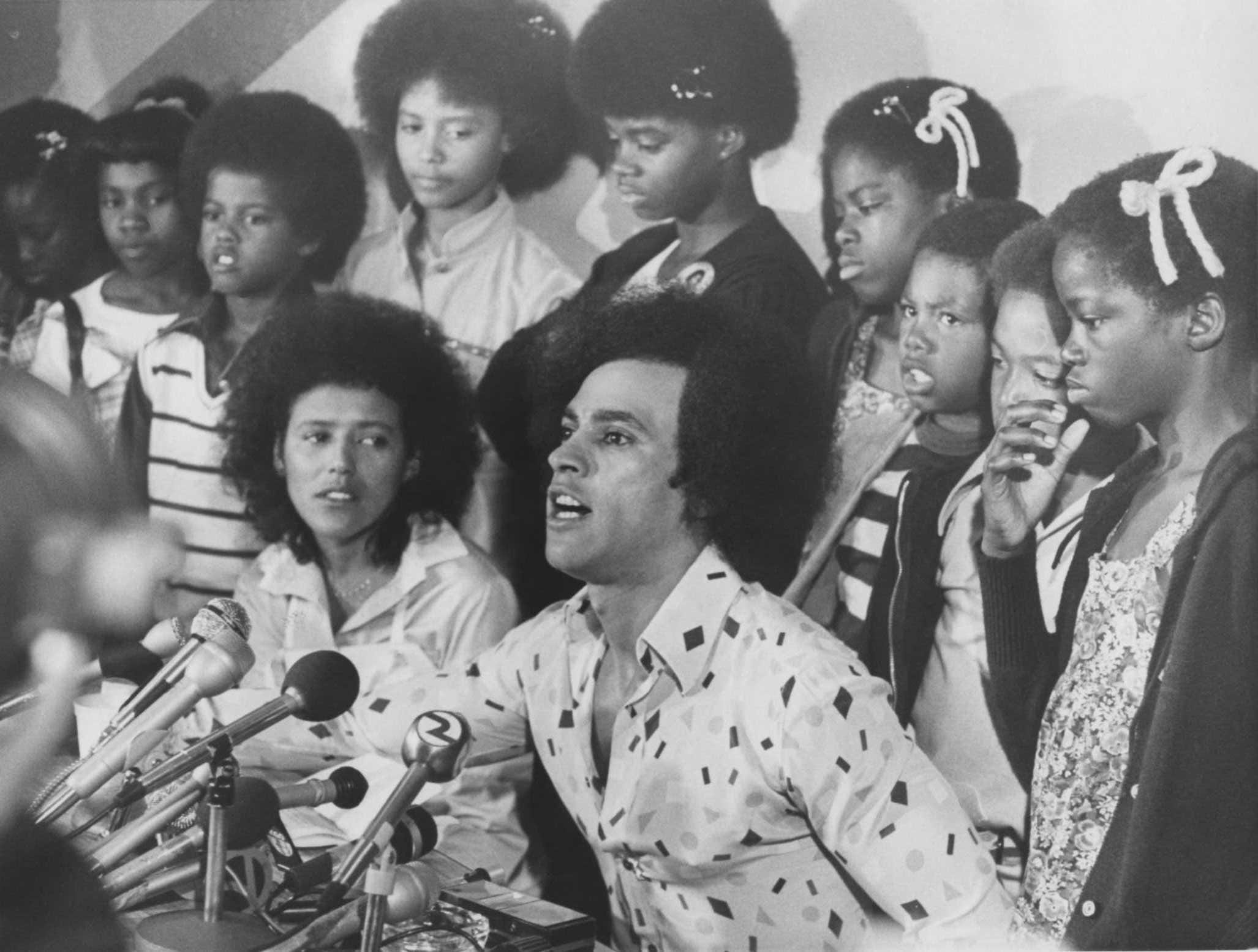

After reading studies on how children who didn’t get breakfast didn’t perform as well in school, the Black Panthers started its Free Breakfast Program, which ended up being one of their most impactful social impact initiatives. It kicked off in January 1969 at an Episcopal church in Oakland, and within weeks, the Black Panthers were feeding hundreds of kids nutritious meals before school every day. The Black Panthers’ solicited donations from grocery stores and consulted nutritionists to make sure they were offering Oakland’s children the healthiest meals they could: usually milk, eggs, meat, fruit, and juice for every child.

School officials said the kids were more focused and doing better in class, and soon, Black Panther outposts around the country followed Oakland’s lead. By the program’s peak in the early 1970s, the Black Panthers were serving 20,000 meals a week to black children in nearly 20 cities. This endeavor served as the impetus for the federal public breakfast programs we have in place today.

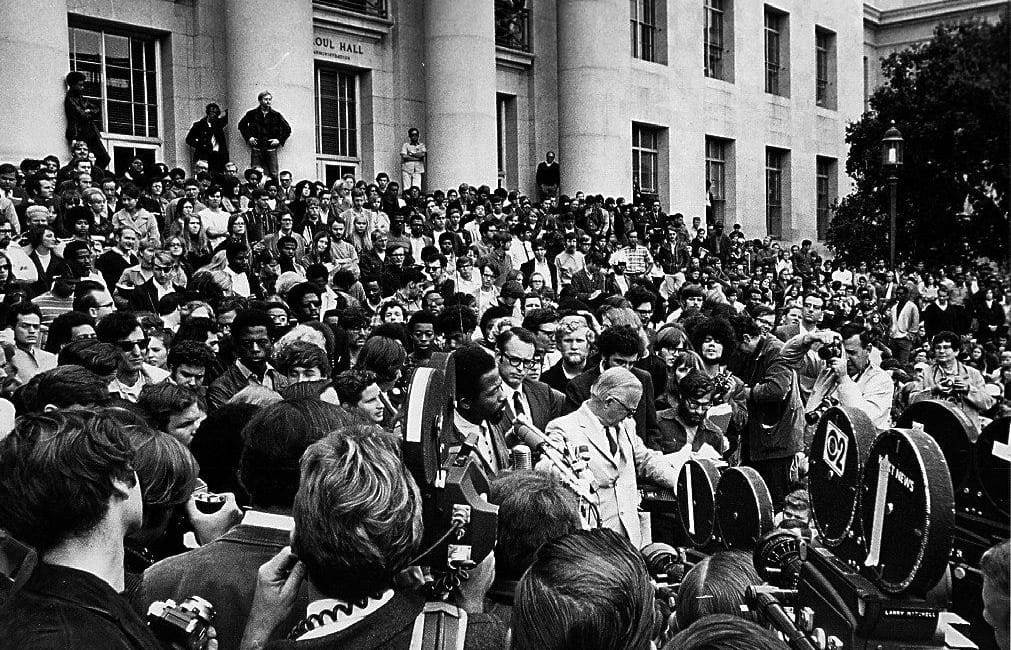

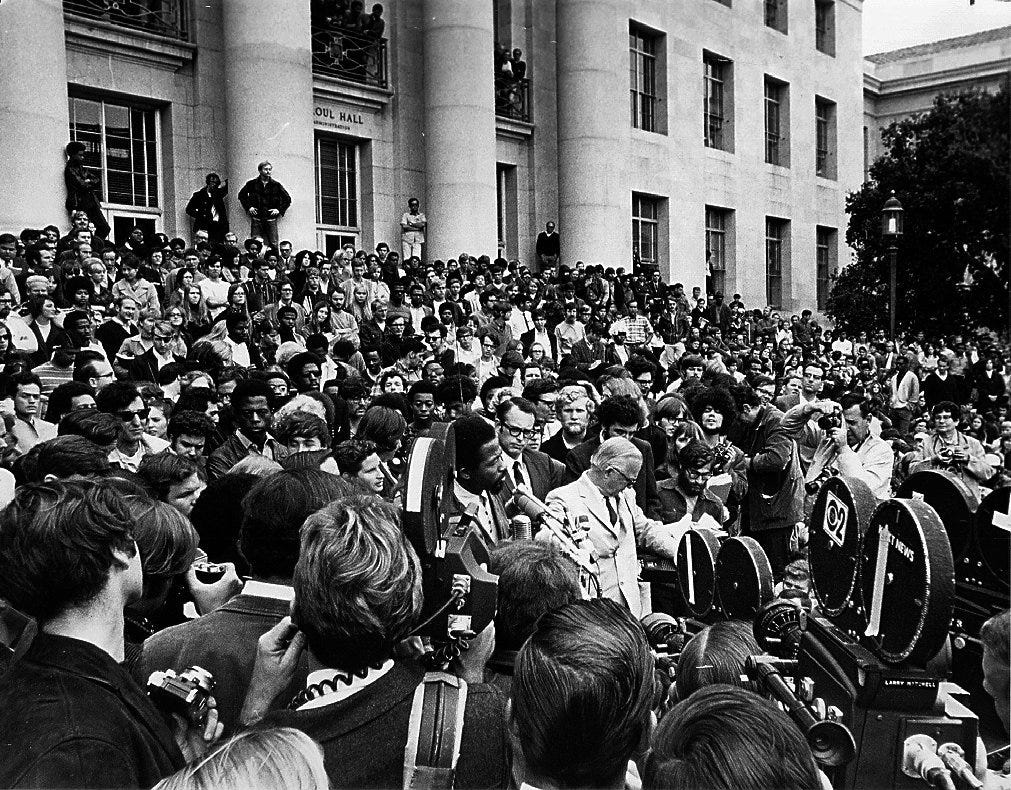

The Black Panthers grew quickly, and by 1968, the group had 2,000 members all over the country, including in Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago. But as we can see in the photos below, the Black Panthers’ remained rooted at home, leading actions and demonstrations in Oakland and speaking to packed crowds at UC Berkeley.

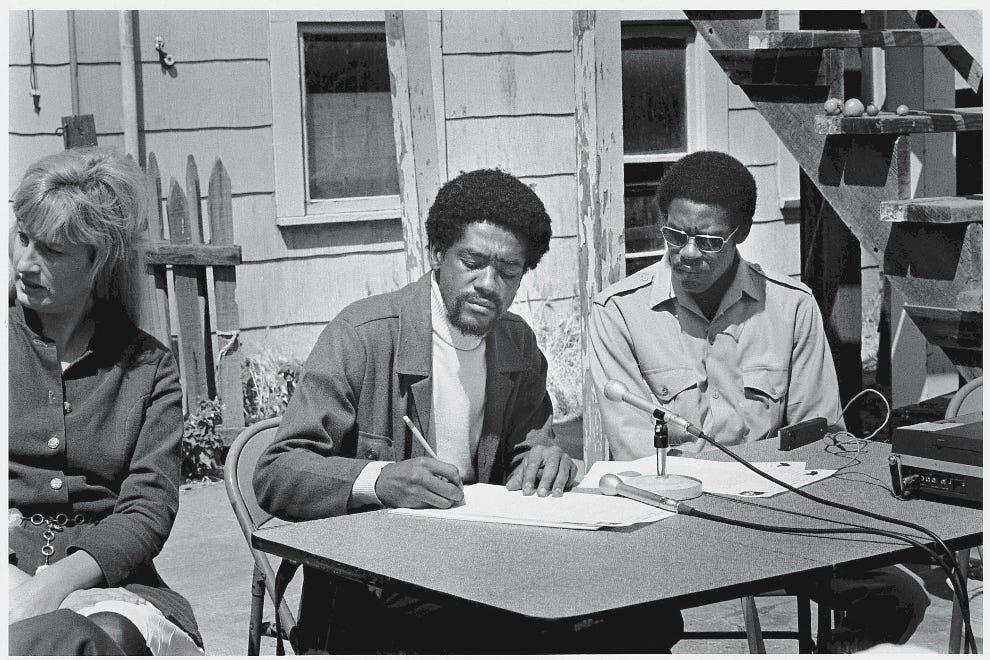

In October 1967, Newton was arrested for the murder of a police officer named John Frey, although no weapon was found on either man. Thousands gathered to protest Newton’s arrest and called for his release at marches like the one in Oakland and across the country, with rallying cries of “Free Huey!” heard around the world.

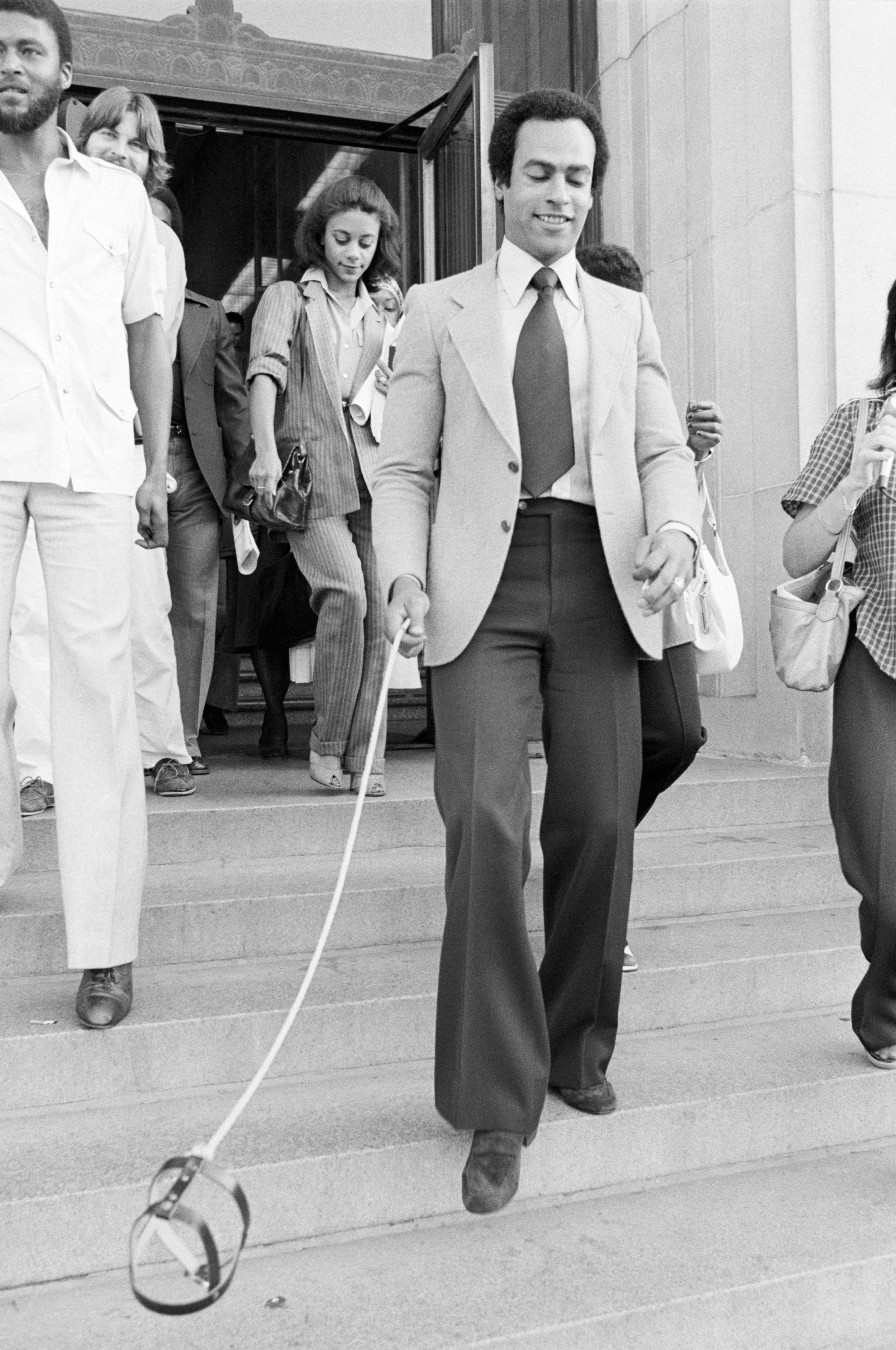

Newton’s charges were eventually overturned, and he was released in August 1970.

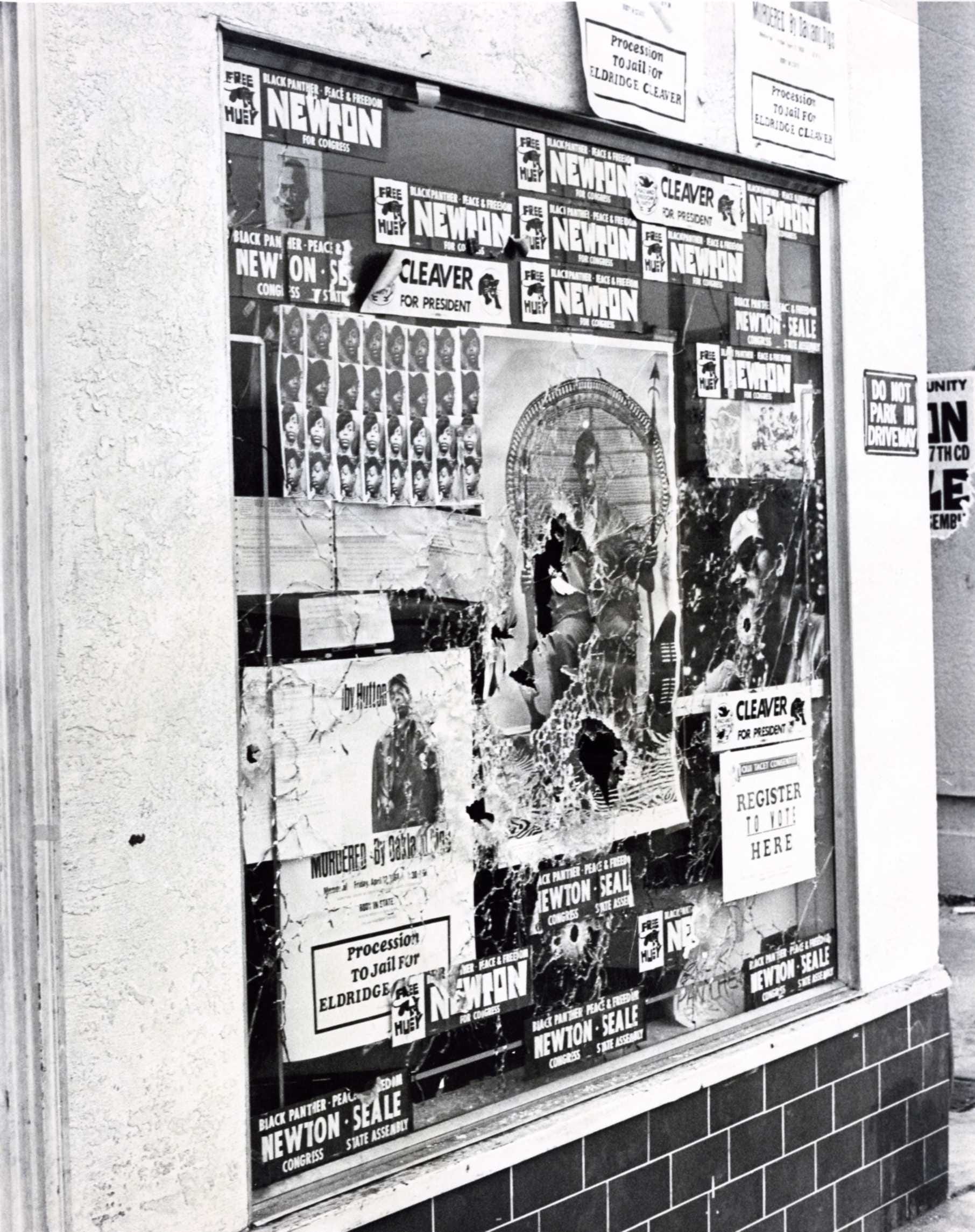

The government — at the regional and federal level — made it a point to target the Black Panther Party. The Oakland Police Department targeted the Panthers through shootings, arrests, and stakeouts. The photos below show the damage to their Oakland headquarters from a shooting by the Oakland Police Department and a stakeout of a home where a Black Panther was in hiding.

The FBI’s first director, J. Edgar Hoover, called the Black Panthers “one of the greatest threats to the nation’s internal security.” The party became the target of a secret counterintelligence program run by the FBI called COINTELPRO, which targeted dozens of social justice leaders in the Black Power movement, the feminist movement, the U.S. Communist Party, the Native American sovereignty movement, and more. The COINTELPRO program was designed to dismantle these groups through both psychological and violent tactics as well as erode public opinion of leftists in general. The group’s actions were secret until a group of activists burgled an FBI office and revealed its records in 1971.

Things escalated for the Black Panthers when the FBI declared them an enemy of the United States in 1969. The FBI, along with local police, worked to dismantle the party and undermine their social programs like the free breakfast initiative by destroying the Black Panthers’ offices and donations and going door to door to tell parents that the Black Panthers were serving poisoned food and teaching children racism. The FBI purposefully pitted Black Power groups like the U.S. Organization (the group that created Kwanzaa) and the Panthers against each other and even contributed to a police raid in Chicago in 1969 that led to the murder of Black Panther Party members Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, who were asleep in their apartment.

Newton tried to keep the Black Panthers alive after his release from prison, but the consistent attacks were weakening the Black Panther Party’s cohesion; and disagreements between party leaders led to many of the veteran members, like Seale, leaving the party. Seale redirected his energy toward working within the political process as the Black Panthers faded, even running for mayor of Oakland in 1973.

Seale, now 83, is still an active advocate for racial justice and has also expanded his work to focus on climate justice and sustainability. Newton fled to Cuba in the mid-1970s, and although he eventually returned, he never fully regained his footing as an activist, and the Black Panther Party dissolved in 1982. Sadly, Newton was murdered in West Oakland by a powerful gang called the Black Guerilla Family in 1989 at just 47 years old.

Today, the Black Panthers’ message of liberation for Black and Brown communities — and an end to police brutality and systemic racism — has lived on. Oakland and the larger Bay Area have always played a crucial role in the fight for racial justice and continue to today.

The protests in Oakland, San Francisco, and other major cities around the Bay Area and the nation are a continuation of decades of activism by civil rights leaders in our own backyard. The Black Lives Matter movement (one of the co-founders, Alicia Garza, is also from Oakland) uses many of the same principles of the Black Panthers.

This moment is hundreds of years in the making.