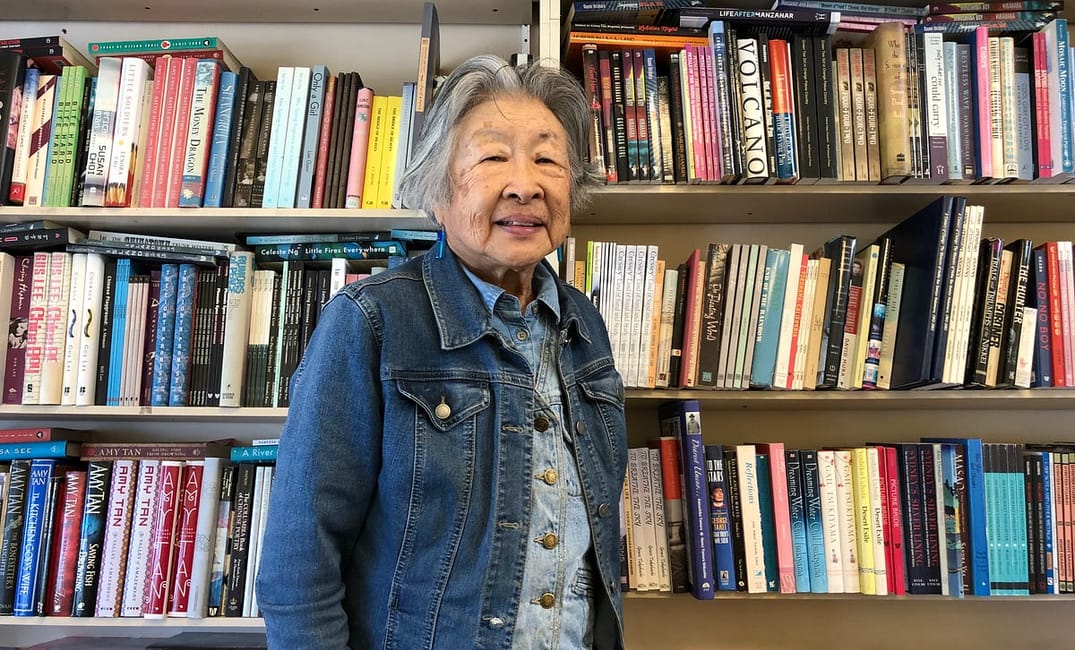

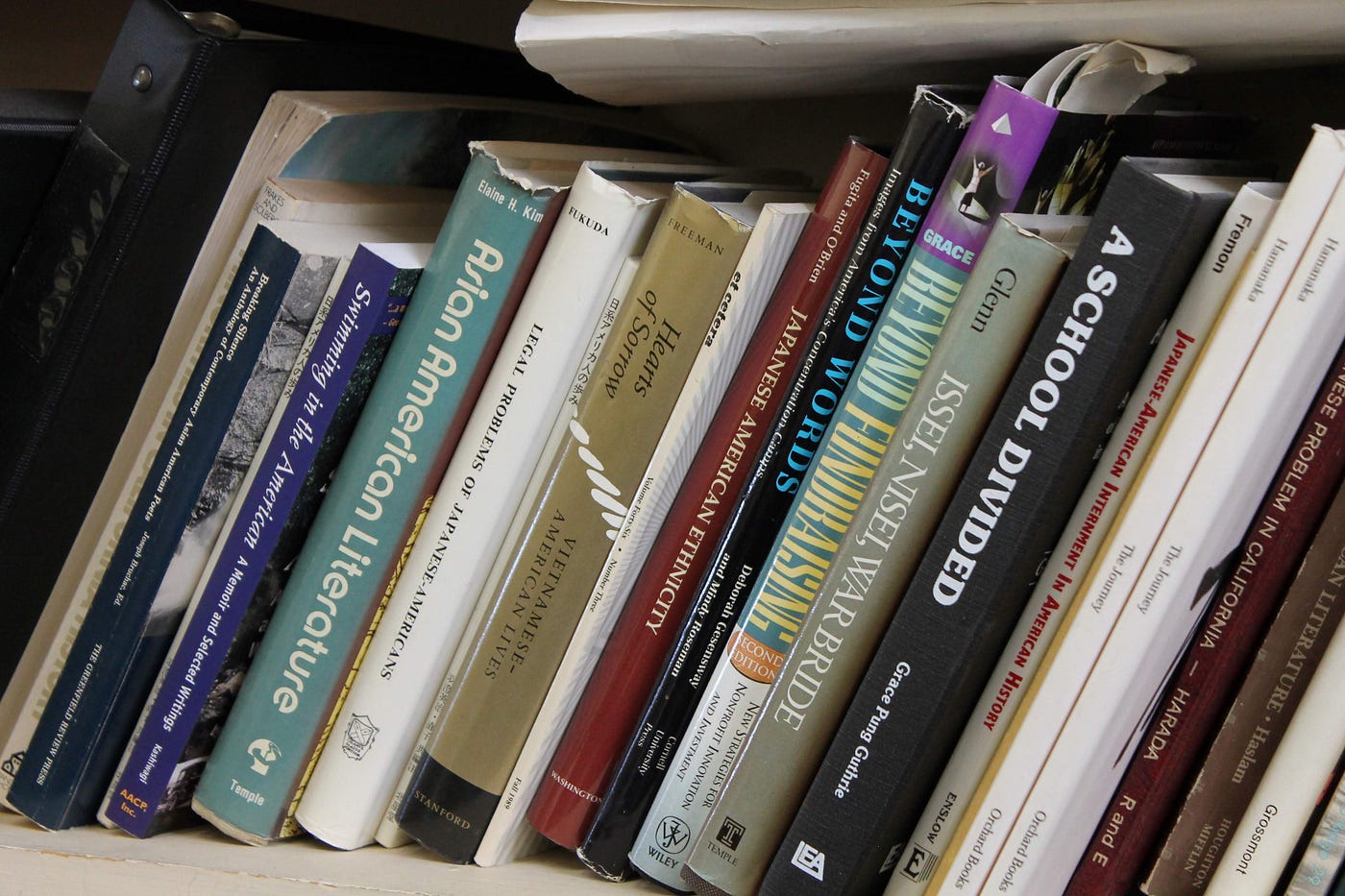

The story begins on the bookshelves. Volumes of Chinese American author Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior sit next to iconic works by Korean American novelist Chang-Rae Lee, which are crammed alongside books by Indian author Arundhati Roy. The newer additions, marked by their glossy jackets, lie horizontally across the tops of shelved literature, like the uber-popular Little Fires Everywhere and Crazy Rich Asians. Across the store, a wide smattering of others include picture books in Khmer, Tongan historical publications and a cookbook devoted solely to Spam.

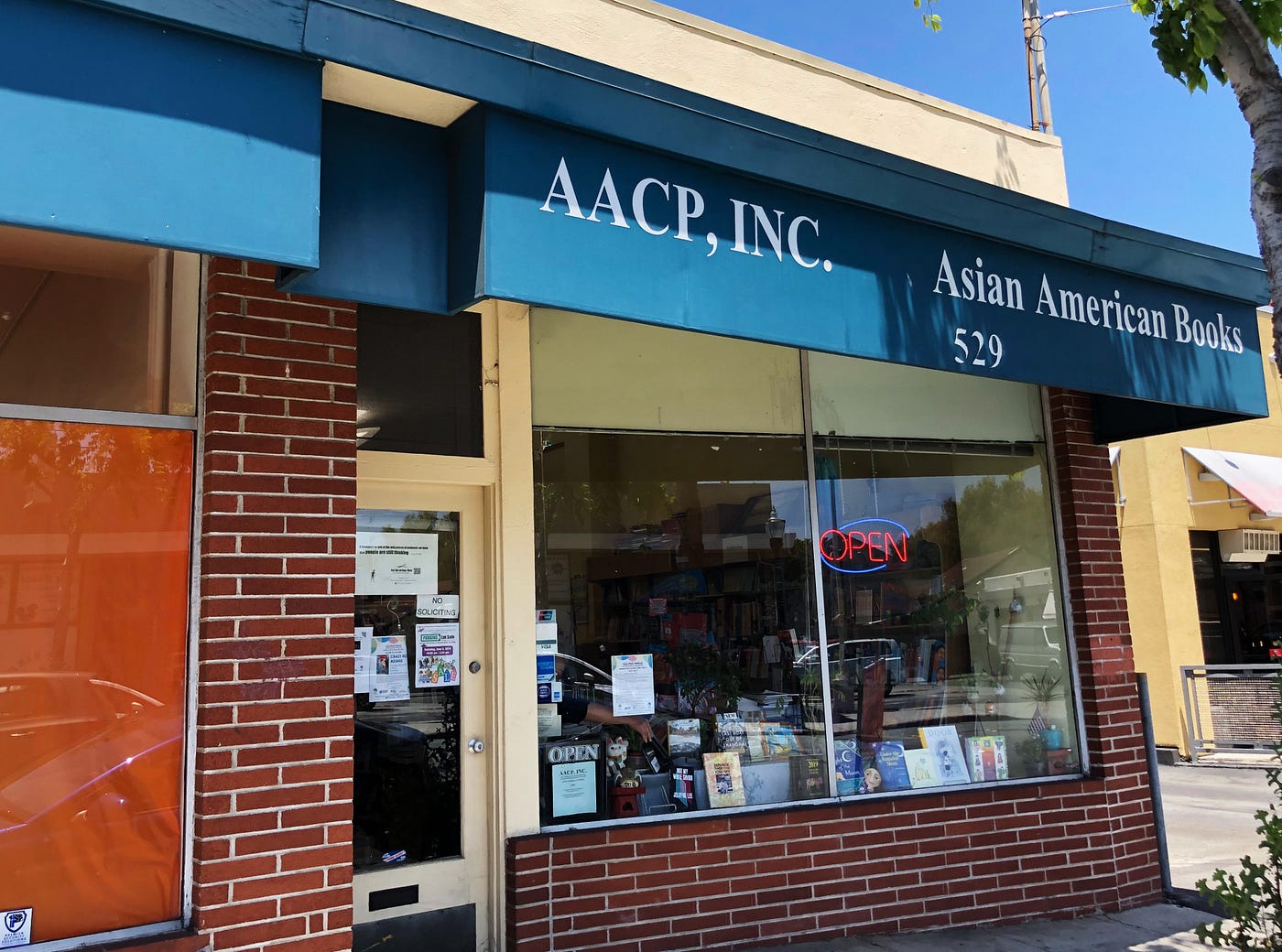

Within this humble store in San Mateo, called the Asian American Curriculum Project (AACP), are the many stories of Asian Americans and, often, the activism they’ve pursued.

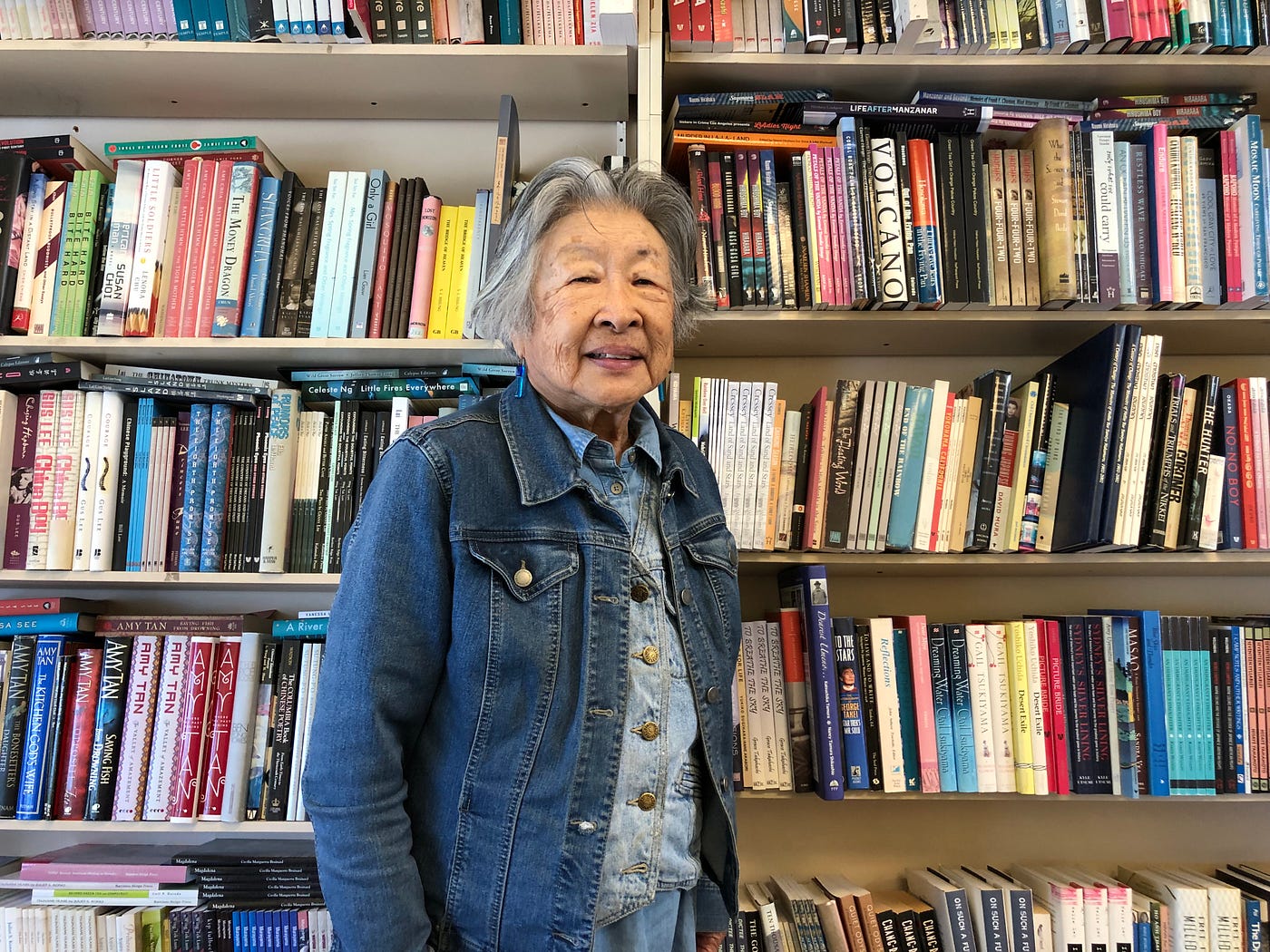

On one particular Saturday, just around 10:00 a.m., volunteers—myself included—gathered near a long table toward the back of the store in an office area separated by desks stacked high with files and boxes. There are seven of us. Most are older with children around my age. I’m 23, the youngest. The table’s center of gravity is owner Florence Makita Hongo. At 91, she’s sharp-eyed; age spots crinkle and bloom at her temples.

The bookstore’s origins are entwined with Hongo’s own history, which encompasses imprisonment at a Japanese internment camp through the Asian American civil-rights movement, when, 40 years ago, she rallied schoolteachers with the goal of combating racism against Asian Americans, using books.

“Activist organizations rely on people’s memory,” Leonard Chan, the vice president of the AACP, tells me. He’s been a volunteer here for over 20 years, and when he says this, we both glance at Hongo.

Outside, the store is nondescript, folded unassumingly among the beige facades on 3rd Street, its to-the-point name announced by a sun-faded blue awning.

Its looks may be modest, but this shop has played a vital role in the Bay Area, where the roots of the Asian American civil-rights movement run deeply. In 1969, against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and the Black Panther movement, a group of UC Berkeley students coined the term “Asian American” to mobilize under a collective political identity. In the 1970s, activists rallied against the eviction of elderly Filipino residents of the International Hotel in Manilatown and joined a multiracial coalition to advocate for the first Ethnic Studies department in the country, at San Francisco State University.

During this climate of change, Hongo, a mother of five living San Mateo, was hired to serve on the school district’s new multicultural advisory staff. She says that when she brought up teaching the history of Japanese internment during World War II, the teachers, who were mostly white, seemed not to know what she was talking about.

But internment was branded into her own memory. Hongo was born in 1928 to Japanese immigrant parents on her family’s farm in Cressey, California. After Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, calling for the interment of 120,000 Japanese Americans. She, then 13 years old, and her family were imprisoned at Camp Amache in Colorado.

Years later, she recounted her efforts to talk about internment in schools, in the bookstore newsletter: “When I first told the public the story about Japanese internment in America, the people did not believe me! They called me horrible names. They accused me of being a liar.”

So in 1969, she, along with 11 teachers and school administrators, started the Japanese American Curriculum Project, or JACP. Sponsored by the San Mateo City School District, they typed out K–12 syllabi and reading lists that highlighted parts of Japanese American history that were left out of textbooks. “Before [prejudiced] attitudes change, a foundation must be built first based on extensive research and documented historical data,” Hongo told the San Mateo County Times in 1969.

In the 1970s, the curriculum project expanded into a bookstore — first in Hongo’s garage, then to a store on 3rd Avenue, in San Mateo, where the JACP invited local Japanese American authors to sell and read their books. The JACP expanded to become the Asian American Curriculum Project in 1985, and its volunteers traveled to schools and libraries across the West Coast with boxes full of picture books, novels and histories.

That’s what makes the AACP so unique: it has always brought the books out of the brick-and-mortar store and into schools and community events, like the San Mateo Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Festival, which the AACP used to organize. “If we bring the bookstore to them, it becomes a really interesting part of a festival,” she said.

In the late ’90s and early 2000s, the bookstore hosted panels and ran a robust newsletter. But running an independent bookstore in 2019 brings a new set of challenges. Grant money has dwindled. Walk-ins are fewer. Overall, the advent of online retail has made it more urgent for the AACP to pour energy into community outreach to make up for people not coming into the store.

“Amazon almost killed us,” said Hongo.

Selling books is usually enough to pay for rent, but when finances are strained, she pays for the bookstore’s expenses out of her own pocket.

Hongo was just one of the original founders. Several others have passed away in recent years, taking with them their community connections and institutional memory. There are only two surviving: Hongo and Rosie Shimonishi, a retired teacher living in San Jose.

“I’m not sure how much longer I have to run this operation,” said Hongo without a trace of sentimentality. It’s unclear who, if anyone, would carry on the bookstore after her.

The blue awning, lightened under years of sun, drew me into the store two years ago. I came in to browse for books and met Hongo working behind the counter. I came back the next month as a volunteer.

The shelves were what had first caught my attention. Packed and overflowing, they recalled a concept that Pulitzer Prize–winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen calls “narrative plenitude.” In a New York Times op-ed following the opening of best-selling Crazy Rich Asians, Nguyen wrote, “We live in an economy of narrative scarcity, in which we feel deprived and must fight to tell our own stories and fight against the stories that distort or erase us.”

I can recall the Asian stereotypes that I had grown up reading: the illustrations in The Seven Chinese Brothers, rendered with lemon-yellow skin. In fact, as a child of Filipino immigrants to California, I couldn’t name a single book or movie that had featured my ethnic identity at all.

Plenitude, on the other hand, constituted what Hongo and the AACP had been advocating for: a cultural bookstore filled with complex representations of people from historically marginalized groups. The bookstore resists racism in the way that only stories can, by providing not only factual historical accounts but also the narrative plenitude that portrays “Asian Pacific Islander” not as a series of stereotypes, but as a multiplicity of narratives that might help advance a more equitable reality.

It’s a mission that seems all the more urgent, as the bookstore’s history recalls uncannily relevant parallels in present-day civil-rights struggles.

“People think that Japanese internment and Chinese exclusion are all ancient history,” says Philip Chin, a longtime volunteer and history teacher. “And then the election of Donald Trump came along.”

In 2018, the Supreme Court officially acknowledged the unconstitutionality of Japanese internment while in the same breath upholding President Trump’s travel ban targeting Muslims.

“I don’t think the Chinese American community is worried enough,” Leonard said.

This fear is consistent with the adage that history, if systematically erased or simply forgotten, will repeat itself. It’s a mission shared, at least in some part, by other bookstores in the Bay Area. Eastwind Books of Berkeley, founded in 1982, carries Asian American literature and hosts authors and artists. Arkipelago Books in San Francisco, founded in 1994, specializes in Filipino literature and culture.

“This isn’t as glamorous as, you know, creating a bill or running over to protests,” said Leonard. “But this is more than just selling books; it’s educating people to be more compassionate to other people and help groups to understand each other.”