People love to suggest that the “authenticity” of Chinatown has evaporated—that Chinese Americans have moved out in droves and that the best dim sum can now be found elsewhere, in places like the western Sunset or the East Bay. But those naysayers, who choose to paint an entire neighborhood as no longer of relevance, couldn’t be more wrong. While there’s no doubt that Chinatown has changed over the past few decades, it’s far from a relic.

I’ve lived in Chinatown for the past 20 years, getting to know the restaurants and the markets, the neighbors and the shopkeepers, the quirks and the charms. The sense of community and tradition run deep here; it’s not hard to see just how crucial of a role the neighborhood still plays in the local Chinese American community. Pick any day to take a stroll down Stockton Street, and you’ll see floods of Chinese people from the neighborhood and elsewhere in the Bay milling about, ducking in and out of shops like New Luen Sing Fish Market and Dong Hing Supermarket, plying their way through bags of bok choy and Chinese greens like yow choy and tong ho. It’s not just the older crowd either—teens continue to fill places like Uniq Salon and S & P Fashion Design Hair Studio, getting their hair done in the latest trendy K-pop and C-pop styles.

Yes, you may be able to find more innovative and trendy Chinese restaurants around the Bay Area, but those new establishments don’t take away from the authenticity of Chinatown’s own eateries, many of which continue decades of service and uphold a tradition of a neighborhood restaurant serving neighbors food they crave.

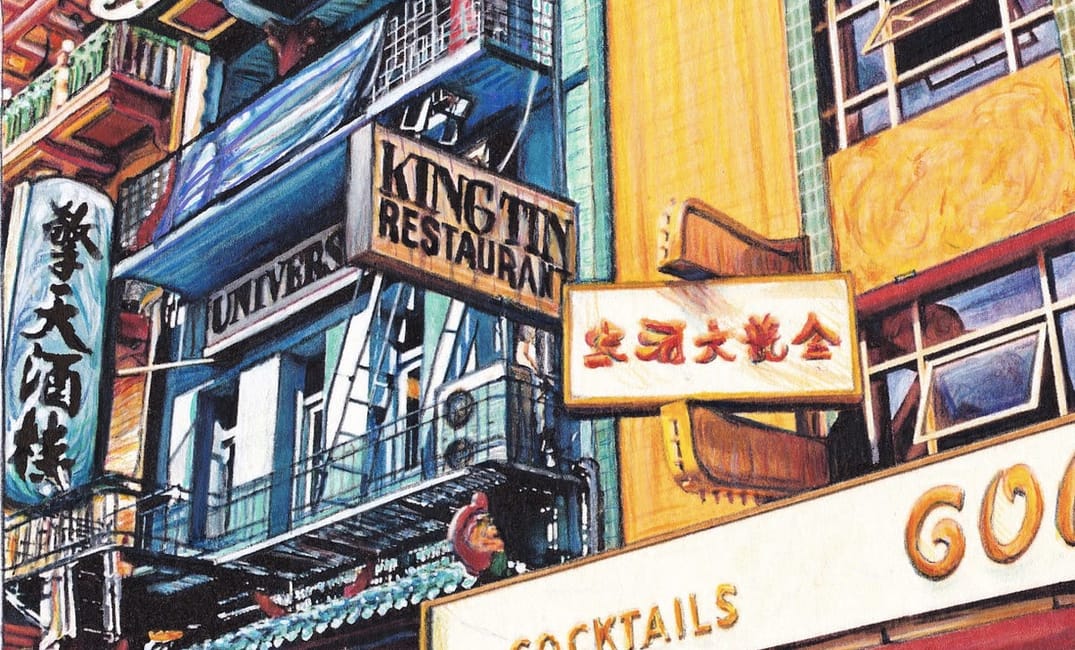

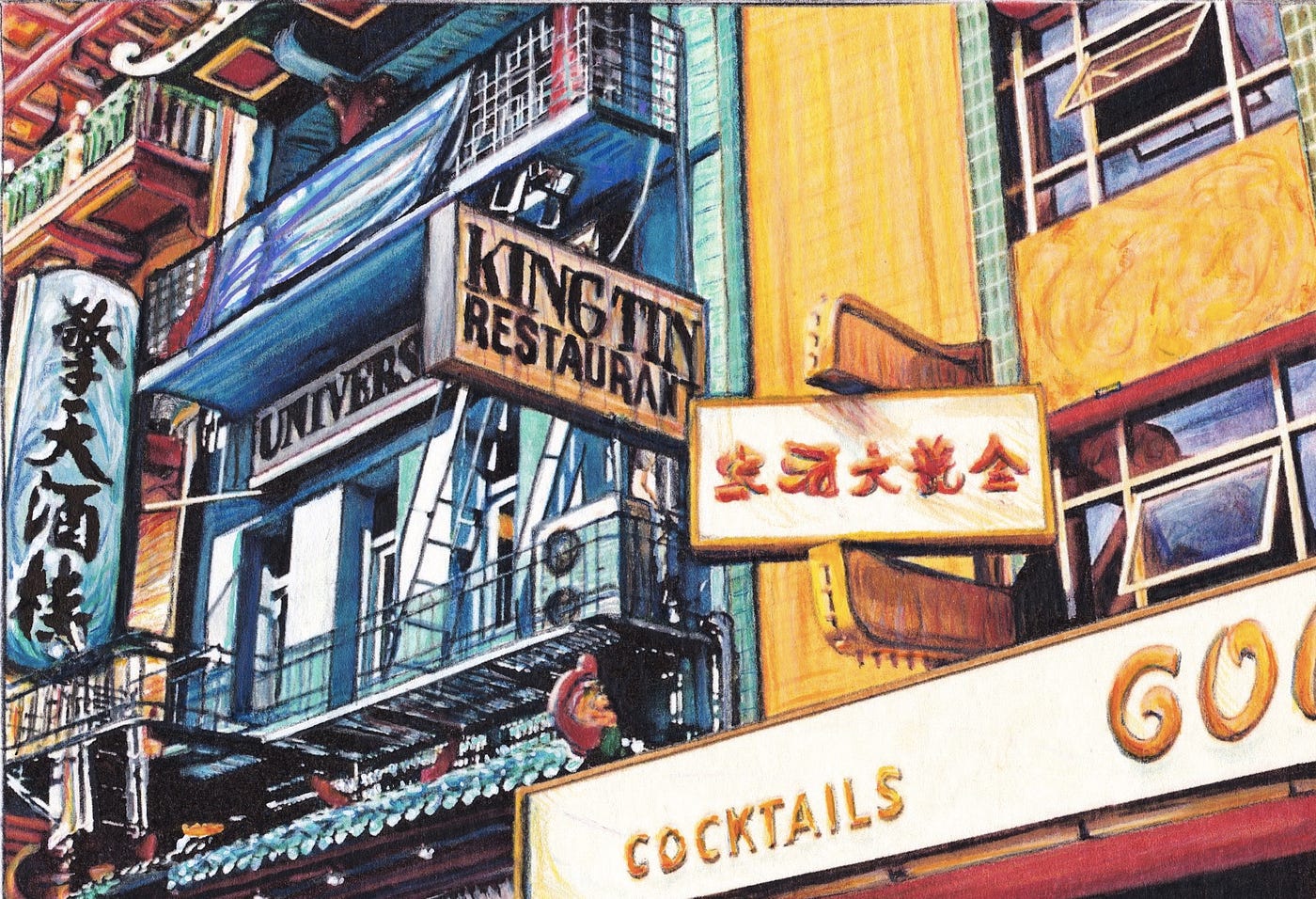

When it comes to food, Chinatown has always been a culinary destination in SF, with longstanding restaurants serving up affordable, delicious regional cuisines of China. Some may complain about their environments, but they remain as busy and beloved as ever even as new, fancier ones have popped up, like China Live. Yes, you may be able to find more innovative and trendy Chinese restaurants around the Bay Area, but those new establishments don’t take away from the authenticity of Chinatown’s own eateries, many of which continue decades of service and uphold a tradition of a neighborhood restaurant serving neighbors food they crave.

San Francisco’s Chinatown arose in the 1850s due to the need of immigrants from China — mostly from Guangdong in the southern part of the country — to have a place to live. The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad especially drew in such immigrants to San Francisco, along with the gold rush. The City of San Francisco permitted the area to welcome Chinese immigrants and allow their property to be deeded to them and passed down to future generations. With these incentives, Chinese people gravitated to the area, and many businesses, including restaurants, sprung up here to cater to them.

While the vast majority of Chinatown restaurants serve Cantonese dishes (including dim sum), it’s home to at least eight major cuisines of China — Anhui, Cantonese, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan and Zhejiang — as well as many more lesser known cuisines.

Of course, much of what we encounter now across United States as “Chinese food” is a cousin a few times removed from authentic Chinese food. In any Chinatown, whether in SF or New York City or elsewhere, people expect to eat more authentic food, food that Chinese people want to eat and not the Americanized version. At their smartest, SF Chinatown restaurants have done just that, creating food for their peers and staying close to their roots.

SF Chinatown is special for thesheernumber of regional fare available here. While the vast majority of restaurants serve Cantonese dishes (including dim sum), it’s home to at least eight major cuisines of China — Anhui, Cantonese, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan and Zhejiang — as well as many more lesser known cuisines. It can be hard to know where to look for the best fare, but there are dozens of both well-known and lesser-known places serving up incredible food, places like the following:

- Hong Kong Clay Pot Restaurant, a bastion of the type of comfort food Cantonese Americans have depended on, including savory chicken, lamb or seafood clay pots; Shanghai-style spare ribs; West Lake beef soup; and Kam Lok’s signature steamed ginger chicken and fish dishes

- Yuet Lee Seafood, which serves up Cantonese-style seafood — think salt-and-pepper squid, garlic crabs, clams with black bean sauce and sides of steamed bok choy — into the wee hours of the night, drawing lines of club-goers, students and police officers on the night beat—an experience similar to late-night Hong Kong snacks

- Hang Ah Tea Room, the oldest purveyor of dim sum in the city and possibly the country, along with Yank Sing, which reigns supreme for a nice sit-down dim sum meal in an atmosphere appropriate for business lunches or visiting relatives, and Delicious Dim Sum, a good spot for quick to-go dishes like har gow, shumai and other dumplings

- Good Mong Kok Bakery, a Hong Kong–style bakery known for its steamed pork buns, steamed rice rolls and dumplings, as well as sweet and savory baked goods (hot tip: get the pineapple buns)

- Z & Y Restaurant, a bulwark of Sichuan in the neighborhood. It may now be a bit overly trendy since president Barack Obama and other luminaries have paid a visit, but it’s still a tasty spot serving classic Sichuan spicy dishes such as lamb with peppercorns, Hunan-style chicken, Dongpo pork and dandan noodles. The much newer Chong Qing Xiao Mian focuses on Sichuan noodle dishes, a staple of the regional cuisine.

- Bund Shanghai, featuring Shanghainese cuisine with the famed xiaolongbao, or “soup dumplings,” plus yang chun noodles, lion’s head (beef meatballs) and a variety of plump steamed buns both large and small.

I could go on. As you can see, with such delicious fare continuing to be served, I don’t fear the importance of Chinatown restaurants slipping. Both tourists and locals are still drawn here, a historic and vibrant place where they can taste a variety of Chinese fare in one walk, whihc is much easier to do in Chinatown than in the Inner Sunset or Outer Richmond. If you’re still skeptical of Chinatown, you should go and hang around, observing for yourself someone trying to carry an impossibly large rice cooker out of a housewares store or people wandering in and out of Louie Bros Book Store clutching magazines from Hong Kong or rare Chinese books on special order. They’re all the daily signs of a very vibrant community at play and at work — and certainly out and about for lunch or dinner, when the time comes.

With so much talk of Chinatown “not being what it used to be,” it’s as if the chattering class would prefer that the neighborhood succumb to a loss of authenticity and be little more than the vast collection of tacky stores selling Asian-themed gifts and furnishings to tourists over on Grant Avenue. But that hasn’t—and won’t—happen.