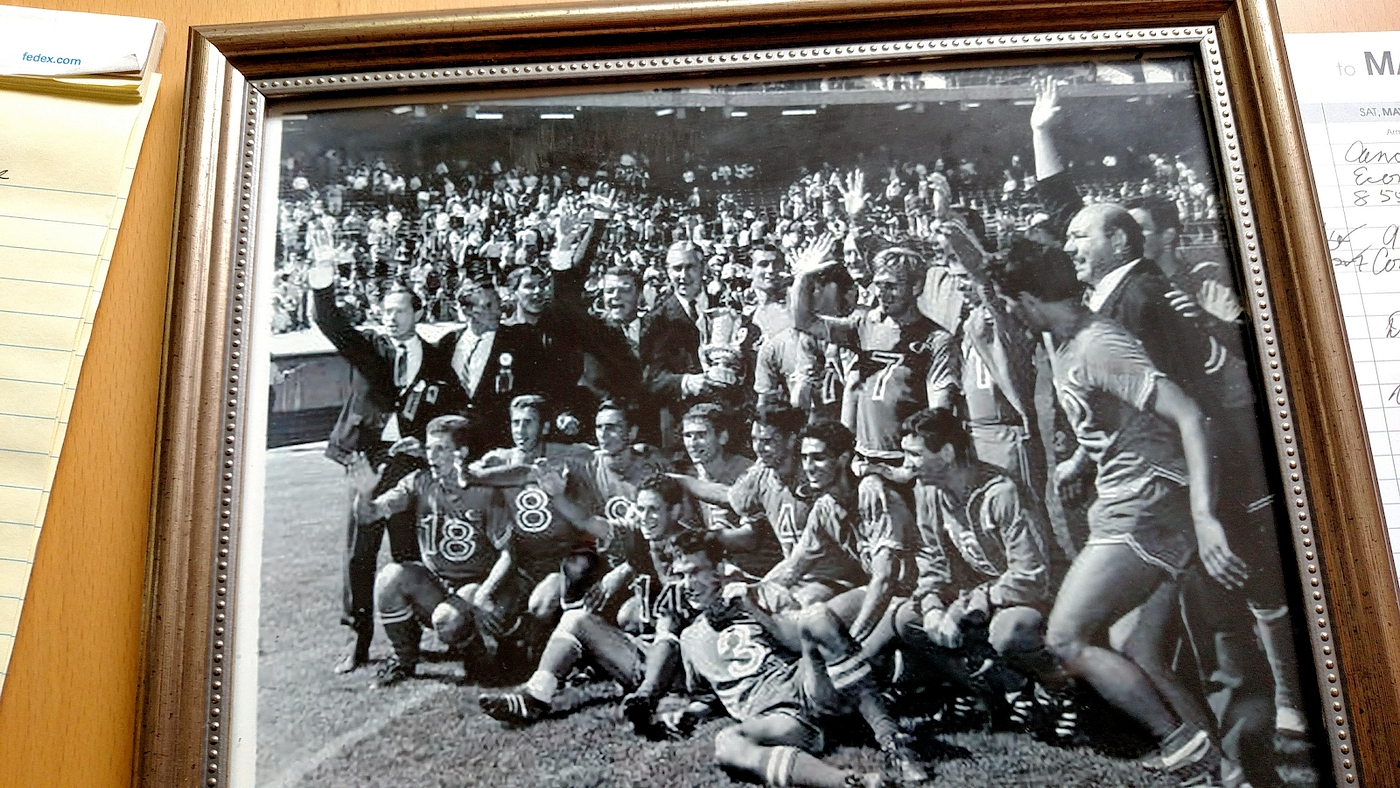

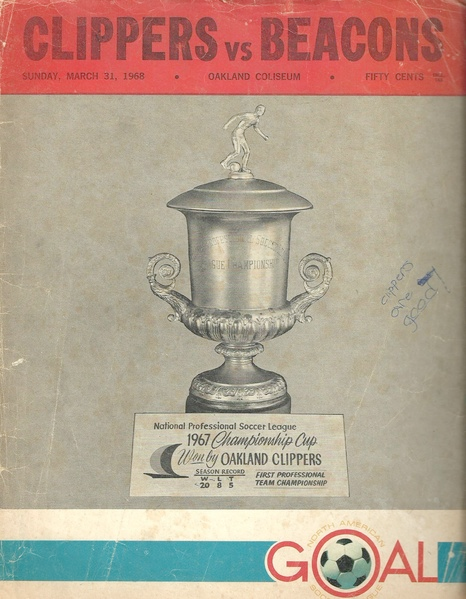

This is a story about the magic of an overlooked era in East Bay sports, about the beautiful and unthinkably improbable run of Yugoslavian, German, and Costa Rican immigrants who came to Oakland as footballers in a time and place where football meant that other, more popular sport that involves helmets and pads and, ironically, no kicking. This is also a tale about the man behind the team, Derek Liecty, a former soccer player who gifted Northern California its first pro soccer organization and helped curate an inaugural championship for Bay Area sports fans.

Maybe you don’t care about soccer. Maybe you don’t care about sports at all. But this is beyond the dimensions of a soccer field or your feelings; this is local legend. What of this legacy and community? What of this group of ragtag renegades who defied the expectations of their times — with nothing more than a passionate zeal for the unpopular game of soccer? What of those who brought the joy and excitement of an international sport to Oakland, California, back when the notion felt about as real as a Berkeley smoker’s pipe-dream? How do we honor that?

This is the story of the Oakland Clippers of 1967.

Derek Liecty’s California soccer dreams

Liecty, who is approaching 90 years of age, is one of the unremembered local sports figures who helped establish the short-lived success of the Oakland Clippers, formerly known as the California Clippers. Even after the team dissolved, he continued to shape the spirit of soccer in not only the Bay Area, but throughout the United States. Prior to the sport gaining any real recognition in the consciousness of U.S. sporting fans, Liecty— a former Stanford standout (he proudly tells me he was the team’s MVP and captain in 1954) — committed himself intensely to the game. His lifetime involvement in advocating for football (er, soccer) in California eventually led him to become a lifelong supporter of the game, even when he could no longer play.

Lietcy’s stories are fascinating and, as he tells me, filled with “insider’s info.” You can hear the zest in his voice as he recalls every memory. Behind each detail, you can sense a young man living in a different Bay Area during the vivid, vibrant 1960s — when the region was more affordable and rebellious, and when an individual’s dreams of building a comfortable home here could be achieved without a $1.5 million dollar price tag.

Liecty played at Stanford, where he learned the tactics of high-level soccer. After finishing, he needed to make a living, and couldn’t do so as a professional soccer player after enduring a grave injury, so he joined the military and later worked internationally.

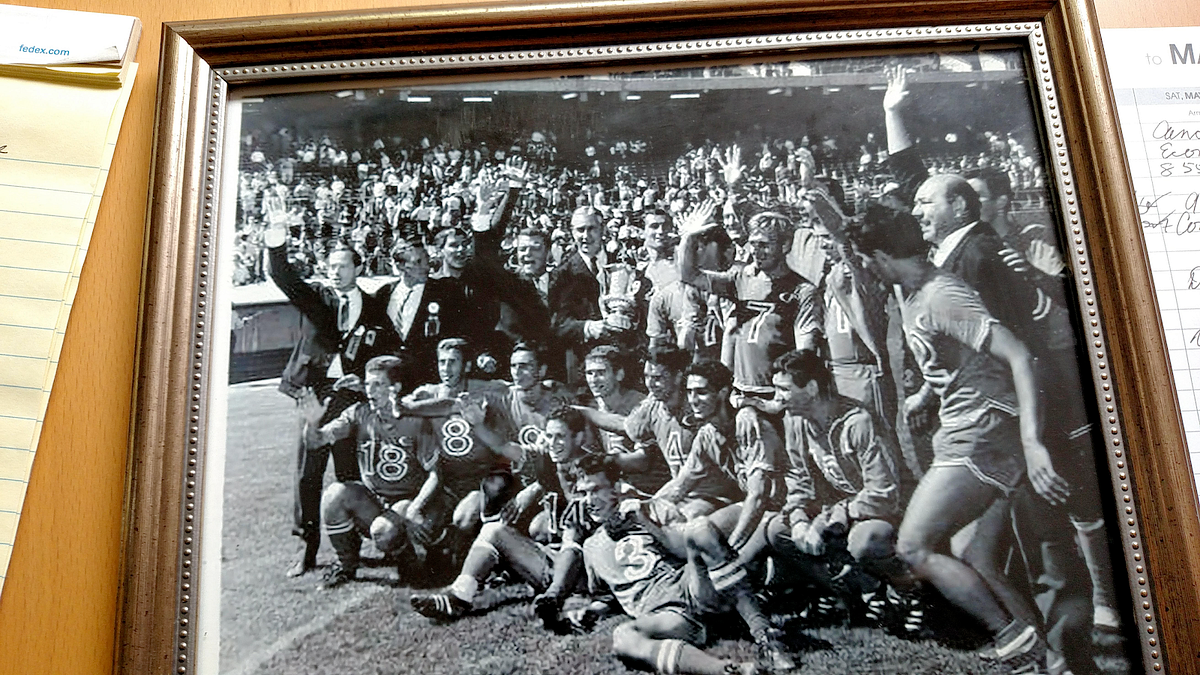

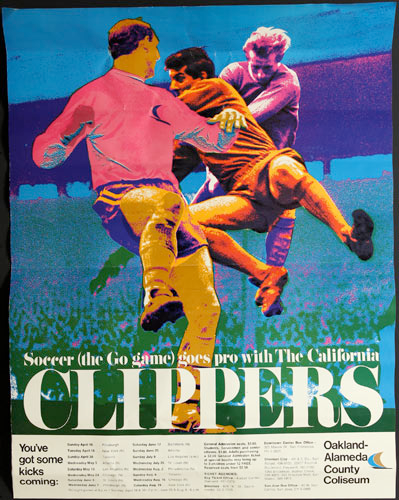

When the chance to return to the Bay presented itself in the 1960s, he migrated to Oakland as the General Manager of the Clippers and brought the region its first championship in 1967 by defeating the Baltimore Bays, a rival that Liecty was very familiar with, having worked closely with the team’s owner to help him gain entry into the world of soccer management. In the process, these teams helped launch a larger U.S. soccer trend. Eventually, the San Jose Earthquakes would emerge, separate from the Clippers, just a few miles down Highway 880, and would become a top-tier team, both locally and in U.S. soccer history, only after the Clippers showed that it could work.

The league collapses after kickoff

After hardships with soccer authorities in launching the first U.S. soccer league, the Clippers went on to host games throughout California against teams from Russia, Brazil, and Mexico — despite disapproval from the FIFA soccer gods, who labeled them an “outlaw” team and refused to show official support, essentially draining the club of any ability to rise in popularity or success.

Like the time the Clippers were able to bring Russia’s soccer champions, the Dynamo Kiev, to play a series of matches on U.S. soil for the first time in American history, much to the chagrin of politicians and other league representatives. But it happened, and it started with a phone call from Liecty’s house on 60th Street in Oakland to the Russian officials.

“This happened during the Cold War,” Liecty recalls. With the league already experiencing cultural and financial backlash, the Russians arrived and played a series of three games, which Liecty remembers as “a great diplomatic and soccer success.”

The teams split the opening games and drew a tie in the third. But as a result, the United States Soccer Football Association (USSFA) was angry at the Clippers for interacting with the Russians without its consent. “After that, we lost the ability to host international teams,” Liecty says.

“Unfortunately, being able to deny our team invitations to foreign teams was the United States Soccer Football Association’s biggest lever to put us out of business.”

Soccer isn’t complicated. But the world of money, politics, business, and fame is. In a time when two major soccer leagues were fighting to become the top-shelf brand for the emerging soccer market in the United States, the Clippers found themselves on the wrong side of the foul line, suffering from a lack of promotion, support, interest, and, as a result, revenue. After their rule-breaking games with Russia, the NPSL was never given official sanction from the USSFA, and thus, a war between the two organizations began, with the Clippers — the top team in the NPSL — as the primary target. Without support from a federation level, the team unraveled shortly after peaking as the inaugural NPSL champions in 1967.

Sports is often more than a group of athletes running around a field; it’s also the sacred intersection for diverse communities to exchange aspiration, pride, and hope in an otherwise chaotic society.

Although the Clippers were the most successful team both on and off the field, the league collapsed only a few seasons after launching, due to rising political and economic tensions with a rival soccer league: the North American Soccer League in 1968. The Clippers, sadly, disbanded just as quickly and unexpectedly as it had emerged. The 1960s, it appears, wasn’t the right time for soccer in the Bay Area, or any part of the country, for that matter. In fact, the Clippers were the final team to play in the American West, scheduling games even after the rest of its competitors had disbanded.

Oakland’s soccer roots are growing

In a way, the Clippers’ radical legacy was not so much about this singular team and championship as much as it was about the greater community that was organically cultivated in the shadows of Oakland’s hills. It reminds us how sports is often more than a group of athletes running around a field; it’s also the sacred intersection for diverse communities to exchange aspiration, pride, and hope in an otherwise chaotic society.

And it all started from overcoming the doubt that Liecty initially faced in San Francisco, before moving the team to Oakland.

“The San Francisco Chronicle’s owner didn’t believe in us,” Liecty says. “He said our team would only bring the newspaper more work he didn’t need, so he sent cub reporters to cover our team instead of real reporters. But those cub reporters fell in love with us, including Glenn Dickey, who went on to become very established in the Bay Area as a major sportswriter after he started out with us.”

Perhaps this is an indication of why Liecty loved playing in Oakland and not in San Francisco, as originally planned. Oakland, in his telling, was eager and willing to collaborate with the Clippers upon the team’s arrival, whereas San Francisco was dismissive. But even with the support of Oakland’s media, it wasn’t enough.

“It was a hard sell,” Liecty admits. “The team went out to do clinics with kids, we tried everything we could to show we were part of the community and this was a new sport, we went through ticket promotions and the whole nine, but the attendance was frankly miserable. That aspect of it was depressing, but for me personally, running the GM position and dealing with the players and visiting teams like Santos and Pele put me in seventh heaven, and I was fulfilling my dream. But it ultimately ended up as a flop.”

The team — which trained in Redwood City, California, on an unused sporting field behind Veteran’s Hospital — faded away in 1969, as did all the other soccer teams trying to fight their way into sports relevancy back then, including the New York Cosmos.

Perhaps the United States wasn’t ready for soccer back then, and maybe we still aren’t. But Liecty still hasn’t given up on his belief that the most universally celebrated game in the world can find success here in the East Bay. He is now unofficially affiliated with the Oakland Roots Soccer Club, a grassroots team playing in the National Independent Soccer Association since 2019 and has quickly gained fans and recognition as one of the few remaining sports teams in Oakland. (The Athletics are the only traditional team remaining after the recent exodus of the Raiders and Warriors.)

So, poetically, it seems this sport that was never given a real chance may finally get its big shot at winning over the hearts of Oaklanders with a culturally diverse, locally owned, and socially aware management, who — like the Clippers, decades ago — want to provide families with a fun, affordable, and authentically East Bay soccer experience, collaborating with independent Bay Area artists like Zion I, The Grouch, Timothy B., and Lateef the Truthspeaker.

When asked why the Clippers never gained the respect or recognition they deserved, Liecty tells me they may have been overly confident and impatient. But, he adds, “we’re doing it better with the Roots. We are being humble and growing the team organically and locally. We’re doing it right this time.”

The Roots may never bring a national title to Oakland like the Clippers did, but, as the name suggests, the team is aware of the legacy that has already been planted in Oakland’s soil. Maybe this time we’ll give them a chance to thrive as a positive sporting organization for local fans — especially in place of the recently jettisoned teams — and show us what it means to feel good, express pride, and just kick it as one unified sports family in these difficult times.

To join Oakland’s new soccer family, head over to Ale Industries on August 29th for a Roots watch party. In true East Bay fashion, money raised from the game and event will be contributed to local organizations as part of the the Oakland Roots Justice Fund, “a charitable fund created by Oakland Roots Sports Club to support racial and gender justice.” For more information, visit the Roots’ website. And who knows, maybe you’ll see Derek Liecty there enjoying the soccer dream he’s always hoped for.