It should be said straightaway that I am biased when it comes to the East Bay Regional Park District. I love it, and I will make no attempt at journalistic detachment. Parks in the East Bay offer the perfect blend of walking trails, scenic vistas, excellent bird-watching, and — best of all — a lot of creepy local history.

Before I start talking about ghosts, the park district has a lot to brag about in general. At 85 years old, it’s the largest urban park district in the U.S., comprising 125,000 acres in 73 parks across Alameda and Contra Costa Counties. But those aren’t the only attributes that keep me coming back; rather, it’s the local history behind them.

“Historical and natural resources are linked, and it’s hard to separate the two,” Ira Bletz, a manager with the park district, told me. “If these resources have value to people, then we have an army of stewards to preserve and protect them.”

It’s almost as though around any bend, you can expect to see a 19th-century miner appear through the trees, walking home after a day underground.

I’m the kind of person who will cross a busy street to read a historical plaque. I’m also the kind of person who insisted on seeing Hereditary in theaters and then couldn’t take out the garbage after dark for three weeks. I love history, and I love scaring myself. So if either of those passions ring true for you, or if you’re just looking to kill some time until the next season of Stranger Things, let me tell you about some local gems.

Black Diamond Mines, Antioch: a deserted mining town

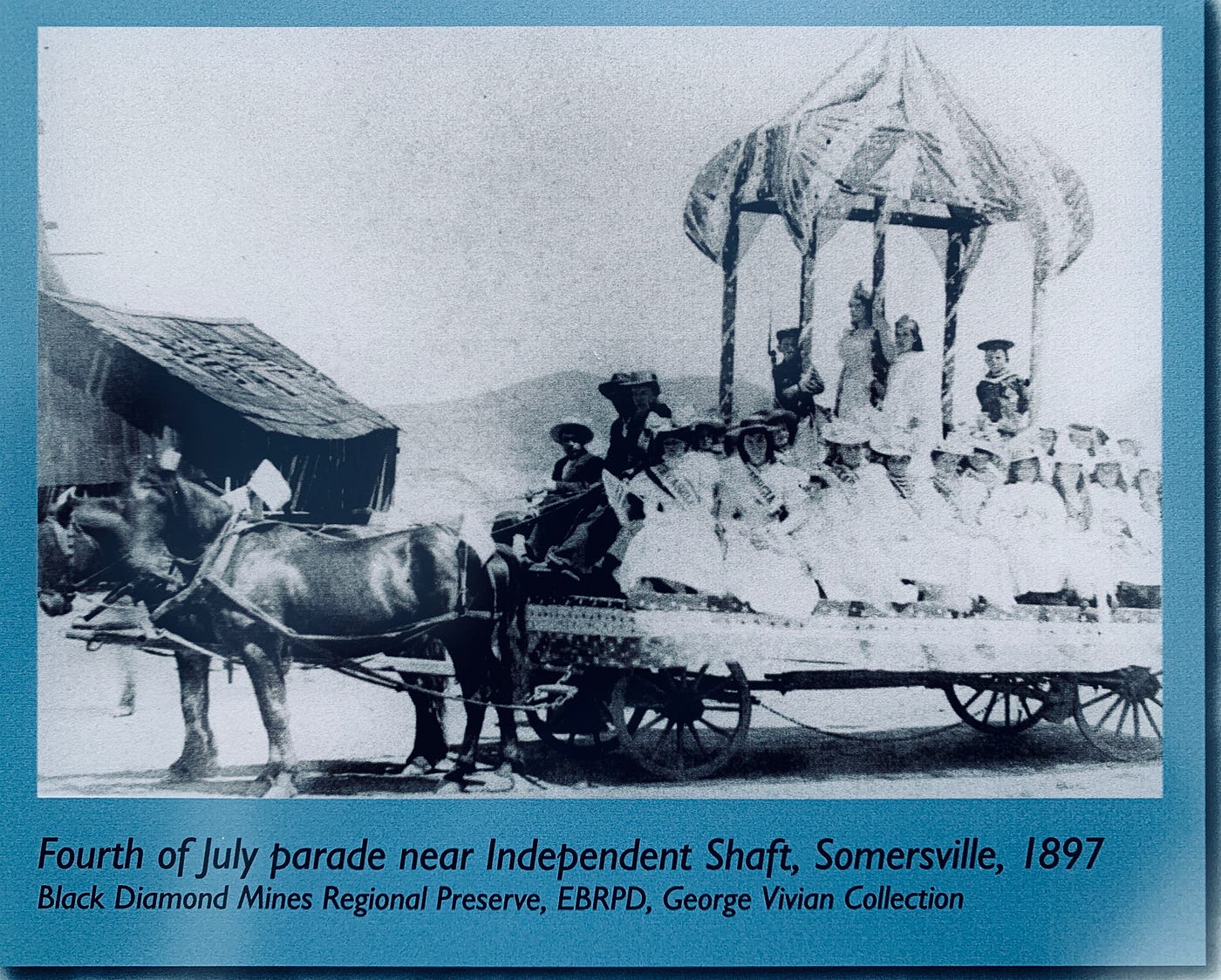

For a little over 50 years, the site of this park supported five thriving coal-mining towns and at one point was the population center of Contra Costa County. Today, it contains over 8,000 acres of rolling hills, red manzanitas trees, and closed mines shafts. There are few visible remnants of what was once a bustling network of towns from 1850 to the early 1900s. During its operation, workers mined nearly 4 million tons of coal from the area before the industry faded and residents packed everything up (including the lumber from their homes) and moved elsewhere. Whatever was left behind was destroyed over the years by fire or vandalism.

After seeing photos of what the town was, it’s surreal to walk down the main dirt path, which is surrounded only by grazing goats. For only $5 a person, you can get a guided tour of the Hazel-Atlas Mine, which produced silica sand between the 1920s and 1940s after the coal mines closed. I’ve taken the tour, and it’s worth the small fee. You’re able to walk through the mines to view fossils, old coal seams, mining equipment, and more, all while wearing an extremely flattering hard hat. The tours are closed for the time being for construction, but a spokesperson promises that an interactive coal-mining exhibit is in the works. I recommend making a reservation when it reopens.

One of the most striking elements of the park, however, is the unmistakable remainder of a town that once was: the Rose Hill Cemetery. A steep climb up the main path takes you to the cemetery. The park district believes that there were at least 235 burials in the cemetery, but only about 80 remain. Before the area became a preserve, the site was nearly completely destroyed by vandalism, and many of the gravestones were lost.

Since the 1970s, the district has worked to preserve the cemetery. It’s possible to get a sense of the families — sometimes several generations — who lived and died there. Many small children died from smallpox or scarlet fever, their gravestones carved with white lambs. Many of the adults were lost to mining accidents or childbirth. Wandering through the graves conveys just how far many of the pioneers came for their chance at success. Gravestones note hometowns such as Ohio and Canada and as far as South Wales and Australia.

Some locals have claimed over the years that ghosts lurk in the area, including that of Sarah Norton, a member of the prominent Norton family and namesake of Nortonville. The district doesn’t support the description of the cemetery as “creepy”; rather, he said they view it as an important and “spiritual” place where locals’ ancestors are buried. I didn’t see any ghosts, but it’s clear how much care has gone into preserving the history of the site.

Other notable stops along the trails include the remains of the Independent Mine Shaft, the spot where a boiler exploded in 1873, killing two men and shooting parts of the boiler as far as a quarter of a mile away. It’s this juxtaposition of what was and what is that gives this park its slightly eerie edge. The site of a heaving killer boiler is now grown over with long grass that’s perfect for meandering goats. It’s almost as though around any bend, you can expect to see a 19th-century miner appear through the trees, walking home after a day underground.

Point Pinole, Richmond: home to a deadly dynamite factory

The previous home of an ill-fated explosives manufacturing plant, Point Pinole today is a lovely waterfront park with more than 2,000 acres of eucalyptus trees, rocky beaches, and the crumbling remains of the Atlas Powder Company, one of the many companies that produced dynamite and gunpowder for over a century.

In 1867, the Giant Powder Company was incorporated in the present-day Glen Park neighborhood of San Francisco. Business was booming (ha), but it didn’t last long. Two deadly explosions were enough to convince the locals that the far-off land of Berkeley was a more suitable spot for a constantly exploding dynamite factory.

Giant Power moved to West Berkeley, now Albany. Unfortunately, moving didn’t quite solve the problem. Two more deadly explosions followed, including one in 1892 that destroyed the plant completely and killed all the workers, reportedly hurling one man all the way into the bay and shattering windows as far away as the Cal campus. Once again, the locals shooed them on down the road after two explosions too many. This time, they were acquired by the Atlas Powder Company and landed in Point Pinole, a remote area that they were able to operate in, apparently without major incident, for decades.

Today, you can check out old equipment, such as the Black Powder Press, a behemoth of a tool used for compacting black powder. According to the historical sign, workers said they “used to go outside when they started [compressing], because you never know if it was going to blow up!” Smart. Clearly, the company’s reputation had preceded them.

Crab Cove at Crown Beach, Alameda: abandoned amusement park

Crab Cove is a certifiably adorable mini aquarium and visitor’s center. When I visited to stare at the chubby starfish and tiny anemones, I was surrounded by a scene that every park district manager dreams of: a parent reading a book about fish to their child in one corner, a couple jogging by with their Dalmatian out front, and a grandpa snapping pics of his grandson climbing around the brightly colored fish sculpture.

Fewer than 100 years ago, though, Crab Cove was a much different place. During World War II, the waterfront visitor’s center was the infirmary for the Merchant Marine base. Before that, it was one building in a large resort and amusement park called Neptune Beach. Now we can all get behind why the site of a military infirmary could fall into the “creepy” category. However, a waterfront amusement park is much less bleak. And in fact, it seems to have been an all-around jolly place — Neptune Beach was known as the Coney Island of the West. It offered prize fights, professional baseball, beauty contests, a zoo, a carnival, and a giant roller coaster.

But when the Great Depression hit, the crowds left; the park went bankrupt; and it was sold off piece by piece in a public auction. Today, it’s just a sunny spot on the bay and clearly a great place to bring kids and dogs. I couldn’t help imagining, though, that after dark, perhaps the strains of carnival music and screams of a roller coaster might still drift over the water.

Coyote Hills, Fremont: shuttered Nike missile site

One of my personal favorites, this early 1,000-acre park is an excellent spot for bird-watching due to its preserved marshes. The hills offer great hikes and views of the salt marshes. A visitors center goes deep on the rich Ohlone history of the area. The center educates visitors on how the native Ohlone used the area’s plant life and resources to construct homes, boats, tools, and more. Local Ohlone tribe members still gather at the site annually for cultural, historical, and artistic demonstrations. In addition to the visitor center, there is an Ohlone shell mound at Coyote Hills, about half a mile from the park entrance. Shell mounds were mounds of earth and organic materials built by native populations over the course of thousands of years, and Coyote Hills is the site of a 2,000-year-old Tuibun village. It’s viewable only by appointment or on special occasions, and you can see the reconstructions of a sweat lodge, a pit house, and other structures near the shell mound site.

But Coyote Hills’ history does not end there. Not so far from the on-site Butterfly Garden is the site of a 1950s Nike missile site. From the 1950s to the 1970s, around 300 Nike missile sites in the U.S. protected against jet aircraft and nuclear threats during the Cold War. The site isn’t for touring, and the batteries are no longer there, but some of the guard stations and communications equipment are still visible.

I toured another nearby site, in Marin County’s Golden Gate National Recreation Area, where a veteran explained that they fully expected to die if they had ever needed to actually deploy the anti-aircraft missile in the event of a nuclear attack during the Cold War. Terrifying.

In addition to massive missile reminders of a world on the brink of nuclear war, the park was home to Stanford Research Institute’s studies with marine animals. As part of their Advanced Sonar Research, they housed dolphins in the marshlands. So the park ended up as a highly varied time capsule of sorts, taking visitors through the centuries — all the way from Ohlone shell mounds to Cold War terror to a study on dolphins.

Whether you’re a history buff or a hiker, the interesting backstories of these parks means they’re more than just pretty trails. The district has taken extreme care to layer centuries of natural, cultural, and human history throughout nearly every park in the system. For me, visiting them gives me a chance to relax, but it’s also a time to geek out on local history and sometimes let my horror-movie imagination take over. Obviously, not every park is going to be the site of a catastrophic explosion or a once-renowned beachfront carnival, but some are. And it’s pretty cool.

“People often think of history as boring names and dates — a bunch of things that happened a very long time ago somewhere else,” said Bletz. “We have the opportunity to bring local history back to something closer. These stories happened here, and they shaped the development of the entire Bay Area.”