This article is part of SF Throwbacks, a feature series that tells the stories behind historic photos of San Francisco in order to learn more about our city’s past.

Covid-19 has completely changed the way we live, and it feels unprecedented. But the world, and San Francisco, has actually been here before, a little over 100 years ago during the deadliest flu epidemic in American history, referred to as the 1918 Spanish Flu. Back then, the city — like now — shut down schools, emptied streets, improvised hospitals, canceled events, encouraged mask-wearing, and most of all, firmly warned to stay at home.

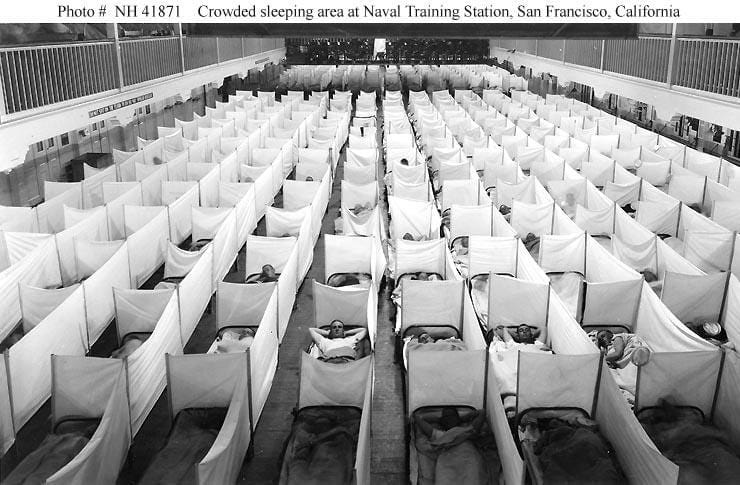

Taking a look back at photos from that year, it can be jarring to see such similarities to today and interesting to see what they did differently (for better or worse.) In the image above, dozens of men lie in a warren of narrow beds separated by simple cloth screens, forming a sea of white. It’s reminiscent of photos we’re seeing today of hospitals crowded with Covid-19 patients around the world. But the men in this photo weren’t sick yet — like us, they’re practicing social distancing. Although… not up to our standards today.

These men were sailors at the Naval Training Station on Yerba Buena Island, and the screens around them were an attempt to stop the spread of the disease altering their world.

The 1918 flu started at the tail end of World War I, when everyone was exhausted and ready for an end to all the fighting. Little did they know, another deadly battle hadn’t even begun. The first case of what would later become known as the Spanish Flu was detected in March of 1918. The epidemic ended in the summer of 1919 with more than one-third of the world’s population having been infected with the virus and more than 50 million deaths. More people died from the disease than from the war.

San Francisco saw 45,000 cases, and over 3,000 deaths. The “Spanish” nickname was coined after Spain’s king at the time, Alfonso XIII, became ill with it and the Spanish media was first to cover the disease, due to fewer restrictions during the war than other countries. Although the actual origin of the epidemic isn’t known for certain, historian J. S. Oxford, among others, hypothesized it actually started in the French trenches.

Much like Covid-19, the Spanish Flu spread rapidly around the world. It was far more severe than the common flu and sometimes fatal to even young adults between 20 and 35.

Similarly to today’s novel coronavirus, city officials believed a returning traveler brought the first case to San Francisco — back then, it was a San Franciscan coming home from Chicago in September of 1918. By mid-October the city had over 2,000 cases. Officials encouraged citizens to wash their hands frequently, avoid crowds, and be cautious about public transit at rush hour. Still, cases climbed, and San Francisco’s hospitals became overwhelmed.

That’s when the city put in place what we now refer to as “shelter-in-place.” After some debate, on October 17 of 1918, the city ordered all “places of public amusement,” like movie theaters and dance halls, to close, in addition to shutting down schools and prohibiting social gatherings.

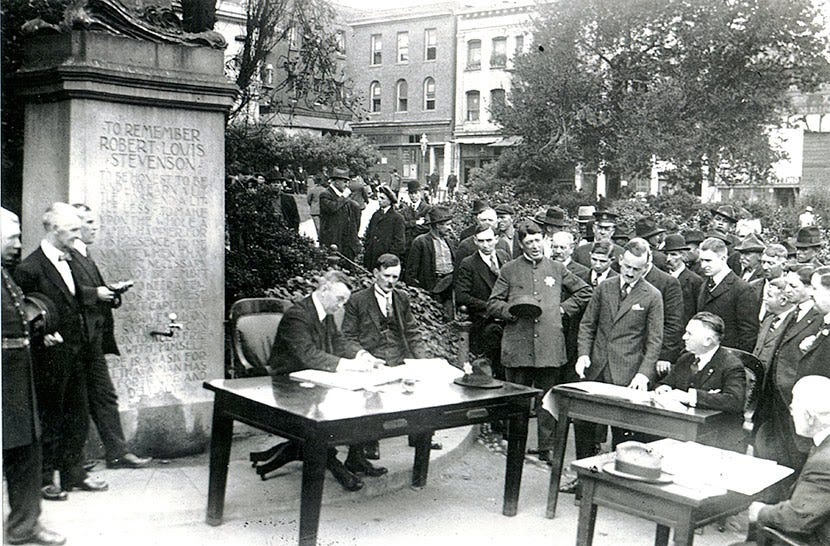

One difference: Rather than postponing court cases as we are doing now, the courts chose to hold fresh-air trials outside. As we can see below in this photo taken in Portsmouth Square, it was a bootstrap operation.

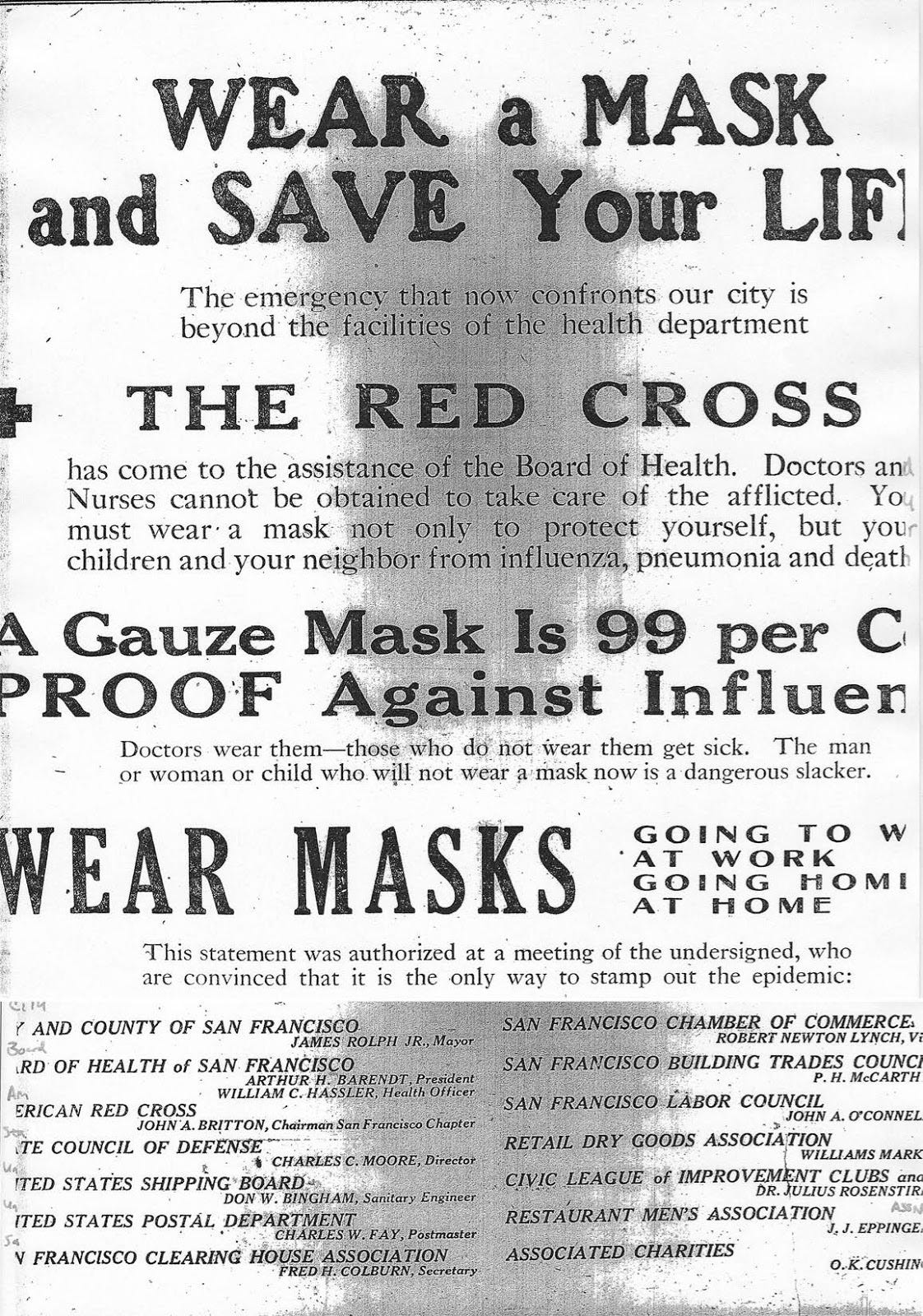

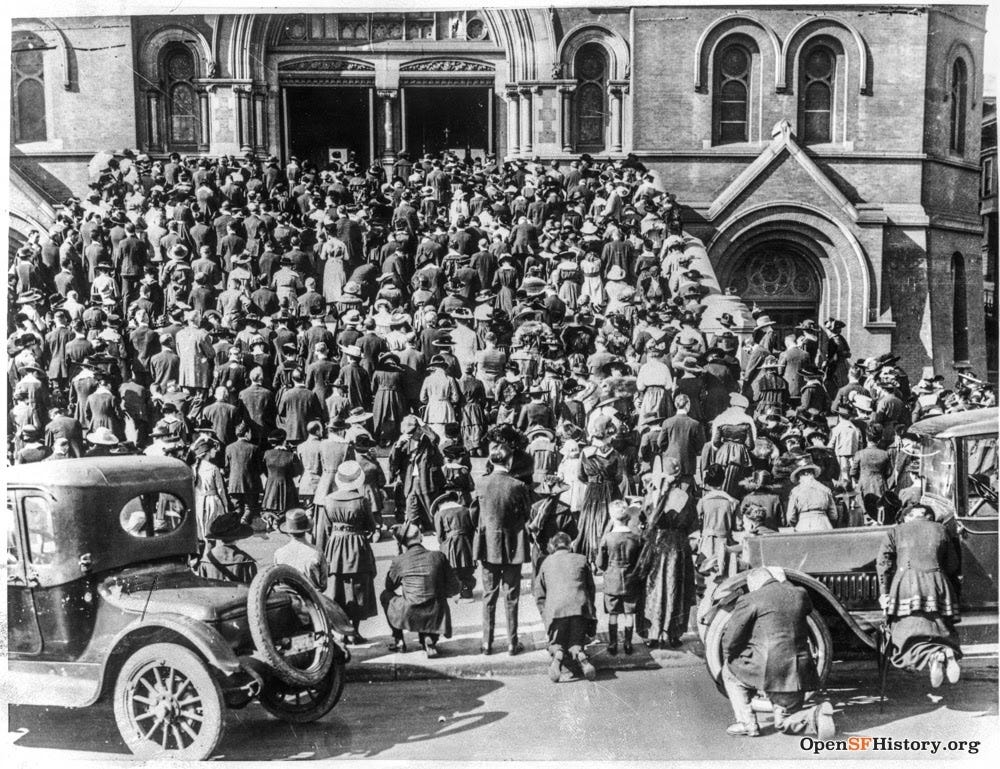

Churches were the only gathering spaces allowed to stay open, but worshippers stood outside with face masks on, as we can see in the photo below of St. Mary’s Cathedral, taken by an unknown photographer. Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear that they got the same memo to stay six feet apart. Everyone at the outdoor Sunday service shown in this photo is wearing a mask, which was required by the city of San Francisco. Anyone who didn’t was a “dangerous slacker,” a Red Cross public service announcement at the time read.

The masks probably helped slow transmission a little, but they were often poorly made from surgical gauze. Nurses volunteered to sew them in large batches in Oakland, as you can see below, but they were thin and small.

When San Francisco’s cases began to drop after two weeks without social gatherings, city officials lifted many of the bans in mid-November of 1918 — a mistake we can learn from. Citizens were still required to wear masks at performances and gatherings, but it wasn’t enough. Like Covid-19, the Spanish Flu spread rapidly between people at public gatherings, and the city didn’t socially distance for long enough.

It wasn’t until February 1919 that San Francisco was free of the Spanish Flu.

San Francisco has survived public health crises before, and we will again. But to avoid the same pitfalls that befell the Bay Area in 1918, we have to do one thing: stay home for as long as needed.