This article is part of SF Throwbacks, a feature series that tells the stories behind historic photos of San Francisco in order to learn more about our city’s past.

As we face an intense election this week, we need all the motivation we can get to keep fighting and stay hopeful for the future. One thing that helps me do that is taking a look at the past and paying homage to our communities’ pioneers.

August of this year marked the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage when Congress ratified the 19th Amendment that granted women the right to vote.

White women were the main beneficiaries of the 19th Amendment, and as such, the movement and key suffragists have long been whitewashed. Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian American women played integral parts in the movement — despite many of them being denied the right to vote due to denial of citizenship, in spite of being granted citizenship, or prejudice at the polls. Historians are still uncovering records of documents, gatherings, and people involved in suffrage that were long hidden. Below are just a few of those previously hidden women.

Before the 19th Amendment passed, women were already voting in many states. California was the sixth state that granted women the right to vote on October 10, 1911 — nine years before it became legal nationwide. The reasons municipalities let certain women vote (and not vote) varied by region; often it was an economic incentive, rather than a humanitarian one. Many Western states granted women the right to vote earlier than the nation as a whole somewhat to push feminist ideals, but more so as a way to attract single women and grow their populations.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

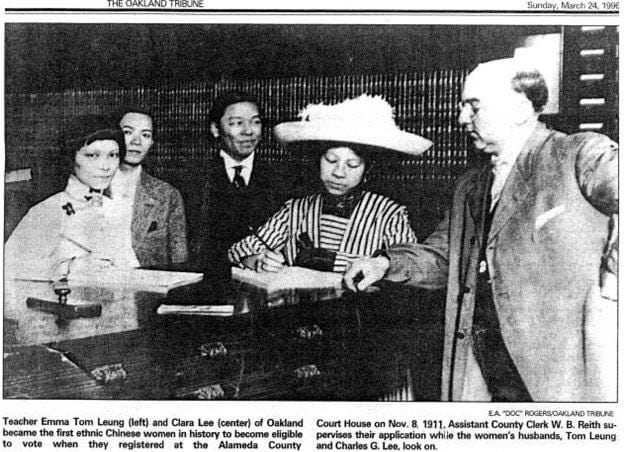

Whatever the reasons, less than a month after California granted women the right to vote, Oregon-born Clara Chan Lee and her friend, Emma Tom Leung, became the first Chinese American — and possibly the first Asian American — women to register to vote in the entirety of the United States when they did so in California. Pictured above is Chan Lee in a regal hat, filling out her voter registration form at the Alameda County Courthouse near Lake Merritt.

Taking her civic engagement seriously, Chan Lee founded the Chinese Women’s Jeleab (Self-Reliance) Association two years later in 1913. The organization used mutual aid to educate women in order to gain independence. Chan Lee continued to advocate for women and the Chinese American Bay Area community until her death in 1993 at the age of 106.

In 1912, just a year after Chan Lee and Tom Leung became the first Chinese American women to register to vote, the San Francisco-born Tye Leung Schulze became the first Chinese American woman to cast a ballot in a presidential primary election in the United States. Leung Schulze voted at a polling place on Pacific and Powell streets. Here she is in 1912, posing in a Studebaker for a portrait.

After casting her ballot, Leung Schulze shared in an interview how she valued voter education, saying, “I think we should… not vote blindly, since we all have been given this right.”

Leung Schulze also dedicated her life to helping women and the Chinese American community. She used her interpretation skills to communicate with trafficked Chinese brothel workers during rescue raids, and was the first Chinese American woman to work for the federal government at the Angel Island Immigration Station in 1910.

She and her husband, Angel Island co-worker Charles Schulze, bucked California’s anti-miscegenation laws, which prohibited marriage between a white person and a person of color, by eloping in Washington state in 1913, though subsequently lost their jobs due to discrimination against mixed-race marriages.

Leung Schulze still showed her progressive feminist colors even in old age. In 1948, at the age of 61, she was arrested in San Francisco for allegedly driving women to abortion clinics when it was illegal. Leung Schulze passed away in 1972 at the age of 84.

Given that the suffrage movement was whitewashed and excluded women of color, the accomplishments of Chan Lee, Tom Leung, and Leung Schulze are remarkable. What’s more, the U.S. was still actively anti-Chinese and anti-Asian in its policies at the time, having established the Page Act of 1875, which prohibited Chinese immigration under the pretense of labor law, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which had no pretenses at all. Chinese immigrants were barred from becoming U.S. citizens under Exclusion, and therefore not allowed to vote. Exclusion was not repealed until 1943.

These American-born women of Chinese descent saw the value of their voting opportunities and seized it, knowing that they lived in a society that did not accept them.

These photos, while celebratory, are also a sobering reminder that people like me — and perhaps people like you — weren’t always allowed to vote. Many of the xenophobic and sexist fears that influenced prejudiced legislation a century ago are still alive today. Building a wall, forced family separation at the border, voter suppression, the threat of health care disappearing, and potential limits on abortion rights are just a few of the bigoted acts that mark Trump’s presidential era. We have far to go.

As I carefully prepare my 2020 ballot for early voting drop-off, I will say these pioneering women’s names and acknowledge the work it took to hold this power in my hands. Many have felt despair these past four years, but change happens over time and with many fights. Some we will win, some we will lose. Every little push forward builds upon the last, moving us forward to progress, to equality. Don’t let the work of those before us go to waste. Please go vote.