For years, there’s been a lot of talk about the need for more venture capitalist funds to go toward founders who aren’t white men — but there’s been very little action. So as Black Lives Matter protests ramped up across the nation, I was excited to read in the press that venture firms were apparently rushing to take real steps toward better supporting Black startup founders.

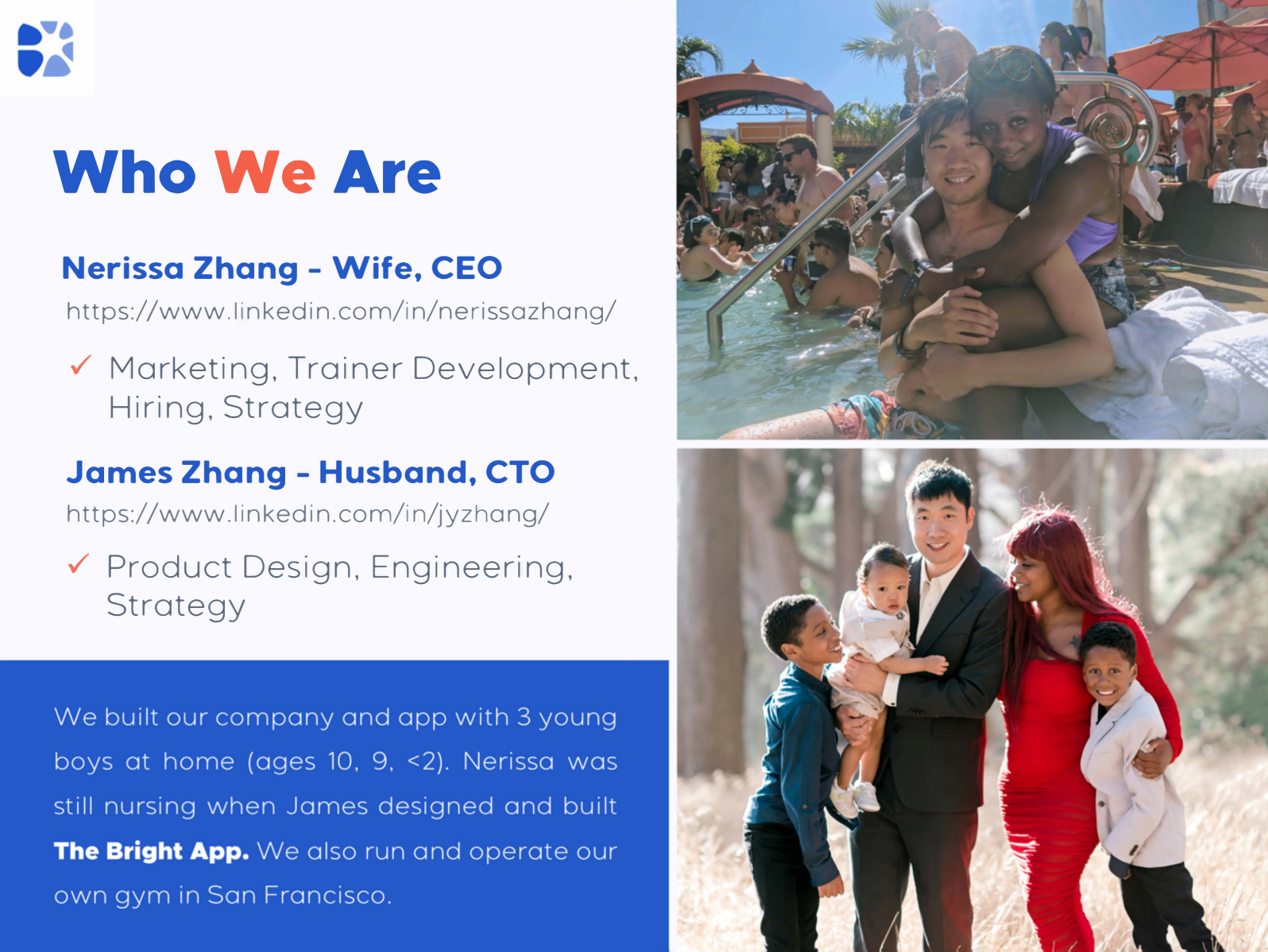

As a Black woman and CEO of The Bright App, a fitness app startup that I co-founded with my engineer husband, I’ve been trying to raise funding since December of last year.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

When I read the news about VCs stepping up their diversity game, I thought: Finally. This time could be different. However, after weeks of trying to get in front of the same investors who were publicly claiming their commitment in the media, it appears their public statements of support were merely self-promotional and stopped short of any real action. It’s clear from my interactions with them that they haven’t changed course in any meaningful way.

This is my experience.

After reading this TechCrunch article, I set out to contact the VCs quoted in the piece about being committed to meeting with and helping Black founders. I started by searching for their contact information — this is where I hit my first barrier to entry. Most VC firms are totally unreachable unless you happen to know someone. This alone makes the process for someone who isn’t already an insider incredibly difficult.

BenchmarkandBessemer Venture Partners, two of the VC firms mentioned in the article, don’t even have emails listed or contact forms on their websites to submit a pitch or deck. Benchmark’s website is almost completely barren, only listing two physical addresses and a Twitter link. Bessemer at least lists their partners on their website, but no emails — only links to Twitter and LinkedIn.

It seems that if you don’t already have a personal connection with someone at these firms, you’re automatically dismissed before ever getting started.

I’m a Black woman, mom of three, and I don’t have an Ivy League degree. My lived experience is very different from a Silicon Valley VC or someone they’d typically work with. I don’t have connections in common with VCs. Does that mean that I don’t have a good idea that deserves a shot? That I don’t have an idea worth pursuing? That I’m not even allowed in the door?

The system of funding new technology lies in the hands of elite, privileged, largely white men, who only associate with people who look like them, went to the same schools as them, and come from the same backgrounds as them. That’s a problem.

My husband, James Zhang, is the CTO of our startup. He is an ex-Google engineer who happened to have a mutual LinkedIn connection with some of these VCs, so I was forced to go through his LinkedIn account to contact these firms. I recognize that is a privilege that many others wouldn’t have: If I wasn’t married to James, and he didn’t have this connection via LinkedIn, there would have been no way for me to even make contact.

After using my husband’s connections to scrape the internet for contact information, I sent our pitch deck from my own email and LinkedIn account to every firm and venture capitalist in the TechCrunch article.

In two weeks, I got zero responses. Not even an automated one.

Recognizing that racism and sexism are both realities, especially in tech, I decided to try another tactic: I sent the exact same emails to the exact same people — but this time from my husband’s email address.

For a bit more background on us, in addition to co-founding The Bright App, we also co-own two successful gyms in San Francisco and have worked together several times in the past — all readily apparent information from our LinkedIn profiles linked in our email signatures. Other facts readily apparent from our LinkedIn profiles and pitch deck: James is a light-skinned Asian man, and I am a Black woman.

Curiously, when I used my husband’s email to send our pitch, that’s when I started getting some responses. Do VCs only read pitches submitted by men? Do they prefer to hear from someone who is Asian rather than Black? I had the same experience four years ago in 2016 when I was raising funding for my previous startup. I got no responses until I started using the email of my co-founder Noah, who is Asian.

Despite much more public support for Black founders in 2020, it seems nothing has actually changed. From 2009 to 2017, startups raised nearly half a trillion dollars of venture capital. Only 0.0006% of that went to Black women, and less than 1% went to Black people overall.

Even when we do raise money, it’s nowhere near what men raise. According to ProjectDiane, only 34 Black women were able to raise more than $1 million in funding for their startups in 2017. The average female founder of any race was able to raise $5 million. Both stats lag far behind those of male founders, who raised an average of $12 million per round.

These numbers are certainly not because Black women don’t have the skills or drive as entrepreneurs. Black women started 42% of net new women-owned businesses between 2014 and 2019, which is three times the average for all women-owned businesses.Black women arethe most educated groupwhen you look at the number of associate and bachelor’s degrees earned within each demographic.

Unfortunately, none of this data on how Black women are excelling on a personal level matters in my quest if I have to be a man or have light skin to even get a worthwhile response from a VC.

Still, I was glad to start getting responses, even though I had to use my husband’s face to get them. The replies were still rare, and the few I did receive were curt and unhelpful. Alfred Lin of Sequoia was one of these few. He replied within a day and asked for our pitch deck. After we sent him the deck, he replied with a short message: “Thanks for following up and sending me your deck. I took a look but I don’t see a fit with Sequoia at this time.”

Listen, I know our app may not appeal to every investor, and we just need to find the right one who understands the value we have to offer. However, given Sequoia’s very vocal claims that it was upping its support of Black founders on Twitter and in the press, I immediately replied back and asked for feedback and introductions. What I got instead was radio silence.

Tellingly, none of the VCs I contacted even tried downloading my app (I use Intercom daily to see all the new users trying our app). They dismissed its worth without even giving it a shot.

Black women are used to rejection and hustling more than others have to, and I’m no exception. If this was before Covid-19, I would be going to meetups and cornering investors in the hallways. In person, at least, I can try to divert their attention for 30 seconds and get some sort of feedback. There are many stories of Black women founders pounding the pavement until they found someone who would listen.

The Great Pandemic has upended all of that. Now, the best chance I have is to use my husband’s email and hope for a response.

The most in-depth interaction I had with any of the VCs I reached out to was with Ha Nguyen of Spero Ventures, who was extensively featured in the TechCrunch article, talking about all of the firm’s apparent initiatives to try to meet with Black founders:

Ha Nguyen, a partner at Spero Ventures, is hosting a Black founders breakfast and AMA lunch on Friday. Nguyen also offered Black founders to reach out when they need help with the fundraising process, pitch deck, and intros for their next check. “And I do hope to write the check,” Nguyen wrote in a LinkedIn post.

However, Ha never replied to my outreach — she only replied after I switched over to using my husband’s LinkedIn. In that instance, though, she was nice enough to give us her email, and I sent her our pitch and deck. Without ever trying our app, Ha wrote back and only said: “The opportunity is too early.” I replied asking for clarification, feedback, and intros just like she had promised she was committed to doing only a few days earlier in TechCrunch.

Instead, she replied with: “Please do read this Medium post I wrote and/or watch the video of the talk I gave on fundraising tips. This can provide some basic knowledge if you’re looking to raise money from VCs.”

If she had reviewed the professional pitch deck I sent her, she would know that I’m beyond the point of needing some “basic knowledge” about the VC funding process. This experience left me feeling condescended to and disregarded. To her credit, Ha did schedule a meeting with me, albeit a month out.

I wouldn’t have been so upset by Ha’s response if she hadn’t explicitly stated in the media the support she promised to give to Black founders. I still have not received her promised feedback or introductions. And her response of “read this Medium post,” drove home the feeling that these public statements of support are all simply self-promotional and an attempt to save face rather than a true commitment to helping Black founders.

Finally, Silicon Valley VCs are notorious for funding startups with only a loose idea in mind. A white or Asian man with the right connections can get funded with a slide deck, no team, and no product. But I want to be clear: I’m not naive. I’m not showing up with only a slide deck and saying, “fund me because I’m a Black woman.” That’s not what’s happening at all.

I spent the last year building my app. We invested almost $1 million of our own funds to find product-market fit and have built a great team. It’s a well-known fact that Covid-19 completely upended physical gyms and private training. Hundreds of thousands of consumers for whom training is a part of their lifestyle suddenly lost their trainer and tens of thousands of trainers likewise lost their source of income.

In the midst of this disruption, we created a way to help both sides of this market find each other. We even created new use-cases that weren’t possible before. No matter how hard you try, you’re unlikely to find an Olympic silver medalist to train you in your local gym. You can with our app right now.

VCs are putting out a lot of statements and Tweets about how they have to do a better job, but as my experience shows, Black founders aren’t seeing any real change.

What we do see is the reality of the VC funding and startup industry, which is clearly represented by this data from Kauffman Fellows and Mac Venture Capital:

- 79.2% of startup executives are White, making them 25% overrepresented based on the number of working-age people in the U.S.

- 15.6% are Asian, making them 160% overrepresented

- 2.6% are Latinx, 85% underrepresented

- 2.1% are Black, 82% underrepresented

Meanwhile, study after study has shown that greater diversity in a company leads to greater success. In the VC world specifically, diverse founding teams are known to have greater returns on investments.

So far, I still haven’t gotten any feedback I can learn from, let alone any VCs to officially pitch and get funding from. It’s been a frustrating experience, and the data shows that I am certainly not the only one being locked out.

Those leading and working for VC firms are the ones perpetuating inequality in their industry. It’s not that Black founders aren’t trying or don’t have companies worth funding. It is 100% that they’re sticking to the same systems which have locked people of color, women, and especially Black women founders out.

If venture capital firms are really serious about leveling the playing field for Black founders, here’s where they can start:

- Make their contact information for pitching accessible to all.

- Respond to founders seeking funding that aren’t just those currently in their network or who look like them. Give constructive feedback.

- Make honest efforts to evaluate Black founders’ ideas, and if it’s genuinely not a fit, explore why that is. And then connect Black founders with other VC firms.

- Prioritize their efforts for Black people and Black women. VCs must go above and beyond their normal efforts to help make up for the many systemic barriers that we face.

- Hire Black women at their firms, especially for leadership positions.

- Track and make public the demographics of their workforce and the people they’re investing in so that they can see where they must do better and we can hold them accountable.

- Read “A VC’s Guide to Investing in Black Founders” in the Harvard Business Review in order to gain a deeper understanding about how “to get into a deal with a talented Black founder, and maintain a positive working relationship that can take [VCs] and them to a successful outcome.”

VCs don’t need to give us any more lip service, they need to build systemic change within their own companies and use their power to hold other VC firms accountable as well.

I don’t want more public statements of support for Black founders. I want access. I want feedback.I want the opportunity to get funding.

Nerissa Zhang is co-founder and CEO of The Bright App, a marketplace and management app for fitness enthusiasts to find and hire a top trainer or coach. She is an elite trainer, a USAW Certified Sports Performance Coach, and an owner of two private gyms in San Francisco. You can find out more at GetBright.app and find Nerissa on LinkedIn. VCs ready to support Nerissa can email her at ceo@getbright.app.