The line ran from the counter through the restaurant’s double-door entrance—past the confined patio, a plot of native shrubs and a stanchion system that zigzagged twice—all the way to the stone façade of the storefront next door. As I joined the pack of what I’d estimate to be 50 people, I overheard a number of similar conversations about the queue.

“We may have to split up,” a woman behind me told a friend.

“Thanks for holding our place,” another person a few spots ahead of me said to her boyfriend.

“How long have you been waiting?” a passerby asked a group several paces ahead.

If I’d closed my eyes, I might’ve guessed it was Saturday night at the Fillmore before a live show. But the intense overhead sunrays and my growling stomach brought me back to where I was: in the middle of the lunch rush at Marugame Udon.

To those who closely follow the San Francisco restaurant landscape, this scene might not come as a surprise. Udon, the traditional Japanese wheat noodle, has been the focus of more than half a dozen restaurants opening in the Bay Area over the past two years, with at least three new shops (Uzumakiya Udon, Taro San and Udon Time) debuting during the past six months.

For years, ramen was the noodle-y Japanese dish to get all the love — the one to spend hours in line waiting for. Now it may be safe to say that udon is taking, or at least joining ramen in, the spotlight.

Why has udon, which isn’t a new thing at all in America (and certainly not in Japan, where it dates back at least 750 years), suddenly become the food of the moment for restaurant-goers?

But why, I wondered, has udon experienced a sudden, swift rise in popularity? After all, hasn’t it spent the last two decades as a sleepy offering at sushi restaurants, situated on the menu next to the bento boxes and the lunch combos? Why has udon, which isn’t a new thing at all in America (and certainly not in Japan, where it dates back at least 750 years), suddenly become the food of the moment for restaurant-goers?

To find out, I took myself on a tour of most of the Bay Area’s udon restaurants, where I spoke to diners and restaurant pros all in the name of good journalism and good eats. Turns out there’s a unique combination of factors at play — and it’s the intersection of all of them that has led us to this udon-crazed moment.

Unlike ramen, which is only a couple of hundred years old, udon has been consumed in Japan for centuries. The most popular style, Sanuki udon, hails from the Kagawa Prefecture on Shikoku Island, where there are more than 600 udon shops that serve the dish all day, including for breakfast and lunch.

The first harbinger of udon’s success as a featured dish in San Francisco was when Udon Mugizo opened five years ago. I went on the recommendation of a friend. What set Mugizo apart from the many other Japanese eateries in San Francisco’s mazelike Japan Center was the noodle machine displayed in the front window, a hulking silver apparatus that could hold a captive audience by converting balls of dough into neatly cut noodles in mere minutes. Unlike the tubular, prepackaged udon I’d been accustomed to, my bowl of udon had sharp, squared-off edges. The strands were slippery and silky — almost to the point of being creamy — and yet they offered a springiness that I’d never experienced before.

“Marugame really set the space for fresh udon.”

But things didn’t really start to take off until Marugame Udon, a Japanese chain with roughly 1,000 locations worldwide, brought freshly made, affordably priced cafeteria-style udon to San Francisco last year. According to Jerome Ito, the chef and owner of the Palo Alto udon restaurant Taro San, the restaurant was the tipping point for the udon trend. “Marugame really set the space for fresh udon,” he told me.

Udon’s glutinous, elastic dough demands so much physicality that it’s traditionally been kneaded by foot, although today nearly all noodle houses employ the help of a similar machine that rolls, compounds, cuts and flours the noodle before it is cooked. Nearly every place I visited employed a machine to transform the basic trio of wheat flour, salt and water into an artisanal pasta. Along with time-tested techniques, such as proofing and dry-aging, today’s udon chefs are using esteemed noodle machines, like Yamatos, which cost upwards of $25,000 to make and serve fresh noodles continually throughout the day.

That sort of attention to quality doesn’t go unnoticed by customers. “Today I got a couple of questions, like, ‘Are your noodles made in-house, or are they made somewhere else?’” said Ashley Robledo, a shift lead at Udon Time, a new udon restaurant in San Francisco. “They care.”

The setup in most udon restaurant kitchens is similar. In addition to the noodle maker, there’s a noodle boiler, an ice bath for blanching so the noodles don’t overcook, simmering pots of broth at the ready and a prep station with every kind of topping. This way, a bowl can be assembled within minutes, sometimes seconds. The idea of ordering; getting a hot bowl of affordable, high-quality noodles; eating quickly; and being back in the office in under 30 minutes has serious appeal.

“It’s very convenient. It doesn’t take long at all, and the food is fresh,” said Greg Hancock, a technical recruiter who was grabbing lunch at Udon Time, when I asked him what he thought of his lunch mid-bite. “It works really well.”

When I asked Edgar Agbayani, the chef overseeing Udon Time, why he thought the noodles were having a renaissance in Northern California, he was quick to respond: “San Francisco is a food mecca, even more so than New York,” he said. “There is a great range of different ethnicities here. Also, it does get chilly quite a bit, so those broth-based items are very attractive to people.”

This proved to be true when ramen overtook the restaurant world in the aughts. After the success of Momofuku Noodle Bar in New York City, fresh ramen made its way west. Its flavor-to-dollar ratio made it an immediate favorite among everyone from struggling college kids to start-up backers. Market research shows that from 2014 to 2018, ramen mentions on menus across the US increased by 46 percent. By the mid-2010s, cult favorites like Mensho Tokyo, Orenchi and Ippudo were turning out hundreds if not thousands of bowls in the Bay Area each day. The dish that epitomized the ramen revolution is tonkotsu, a deeply savory, stick-to-your-ribs version made from long-simmered pork bones that packs enough calories for an entire day.

But in many ways, the popularity of ramen also contributed to its downfall. Ramen shops in San Francisco became so ubiquitous that new openings seemed mundane. And with the rise of avocado toast, grain bowls and wellness culture, onetime tonkotsu fiends found themselves seeking a replacement that provided the same kind of hug in a bowl without being so greasy. Udon fit the bill perfectly.

“Udon is the healthier version, and that’s always the option people look at,” said Agbayani. He explained that whereas a tonkotsu soup base is made with pork stock and fat, udon is made with dashi, a seafood broth. “You get plump, light noodles and a super-vibrant fish stock with mackerel and bonito.”

It’s also agreeable to consumers with dietary restrictions. Every one of the area’s udon specialty shops can make a vegetarian or vegan option, and since many of the restaurants have a self-service, cafeteria-style format, customers can easily cater to their own specific nutritional needs, supplementing udon with eggs, doubling their meat or adding vegetables without any inconvenience.

“We’re doing some udon bowls that come out to almost $60 a bowl.”

Then there’s one other reason why udon has cultural relevance in a post-internet era. An entire group of eaters, Gen Zers, grew up associating ramen not with square-shaped packets of squiggly noodles but with made-to-order bowls at places such as Ippudo. It’s the same demographic that’s never known a world without social media, the same generation that spawned social media novelties like 24-karat-gold wings, rainbow bagels and the “noodle pull,” a photographic phenomenon that involves Instagram influencers lifting obscene amounts of noodles high above their servingware in restaurants. For those people, udon is not only easy to understand but also easy to share socially in performative ways.

Ito laughs when he tells me that he learned about noodle pulls only recently when a few Instagram influencers staged an impromptu photoshoot at Taro San. But the infatuation with newness and excess has taken him by surprise, as diners are customizing their udon in unexpected ways.

“We’re doing some udon bowls that come out to almost $60 a bowl,” he said. “They’re doing an uni ikura [sea urchin and salmon roe] udon but adding double uni, adding fresh truffles and adding a panko egg.” No doubt a photo of all that piled into one bowl would hit the Instagram jackpot.

And then there’s one last truth: there’s nothing San Franciscans love more than a new dining obsession that they can share with all their friends on social media. Just look at Gram, the jiggly soufflé pancakes fresh from Japan that customers spent up to four hours lining up for to eat this weekend.

So are artisanal udon places poised to be as widespread as ramen shops in the future? “It’s not going to be like poke—I guarantee that,” Ito, who also owns a chain of poke restaurants, said laughing. “You can’t learn here unless someone teaches you. You’ve got to go to Japan.”

Want to go on your own self-guided tour of Bay Area udon spots? Here are a few to check out.

Udon Mugizo: The first udon restaurant to open in San Francisco, this full-service restaurant has at least 30 different udon dishes on its menu. One of the most popular is its signature uni cream udon, topped with sea urchin, shiso leaf and salmon roe.

1581 Webster Street #217, San Francisco |

mugizo-us.com

Kagawa-Ya Udon Noodle Company: One of the most unique offerings at this Mid-Market restaurant is the Spicy Beef Tan Tan Udon, a take on Chinese dan dan noodles with ground beef, scallions, bean sprouts and a spicy miso-sesame sauce.

1455 Market Street, San Francisco | kagawayaudon.com

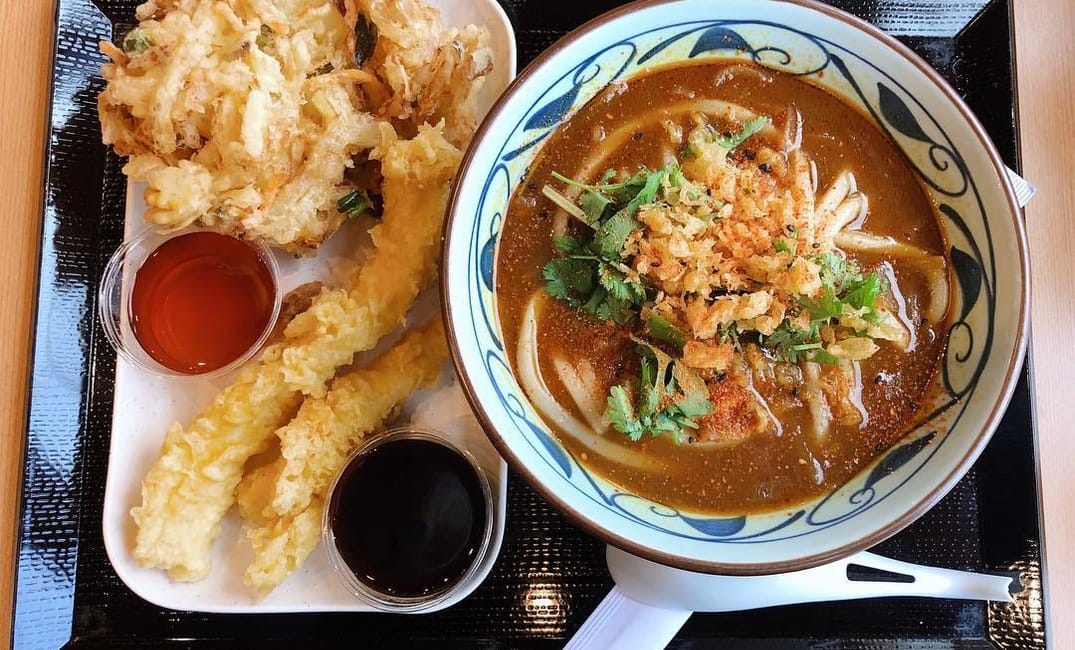

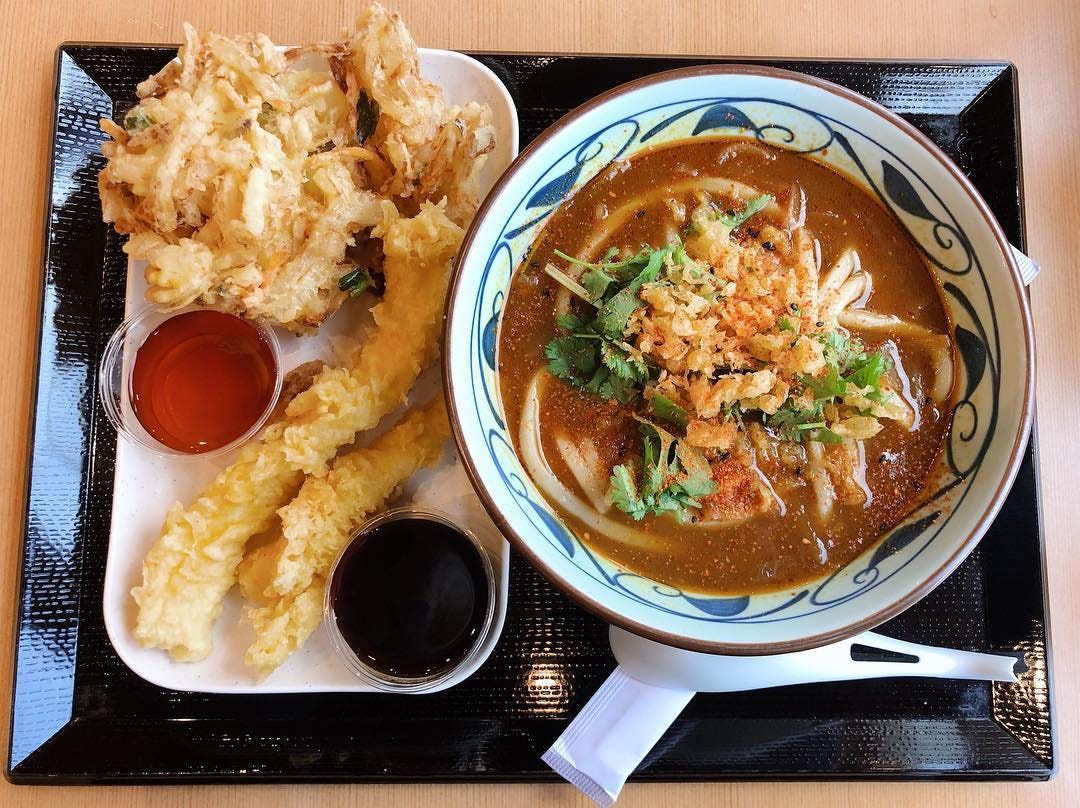

Marugame Udon: To get a sense of what may have arguably started it all, visit the San Francisco outpost of Japanese mega-chain Marugame, located in Stonestown Mall. Don’t be put off by the line, which moves quickly. With almost every bowl priced under $10, you don’t have to stick to just one. 3251 20th Avenue Space 184, San Francisco| marugameudon.com

Udon Time: This new concept from Omakase Restaurant Group (which owns Niku Steakhouse, Omakase, Okane and others) is a good introduction to udon 2.0. Try the Niku Udon, which comes with a choice of wagyu beef or Berkshire pork, or the Kamatama Udon, a dry dish that’s made with bonito flakes, soy, parmesan and egg, for an East-meets-West version of carbonara. 55 Division Street, San Francisco | udontime.com

Taro San Japanese Noodle Bar: This full-service udon restaurant in the Stanford Shopping Center knows its customers. While you’ll be greeted by a host, all your ordering is done via menu screens at the table. Here the udon is made daily in three different sizes, which correspond with various dishes. We loved the chef’s Duck Tsuke Udon, which featured the thinnest version, had the best bite of everything we tried and was served dry with a warm dipping sauce on the side.

717 Stanford Shopping Center, Palo Alto | tarosanudon.com