Today, West Oakland’s Seventh Street isn’t what many would call idyllic. Save for a liquor store, check cashing center, or grocery co-op, many of the buildings are vacant and padlocked. The guts of sprawling tent encampments spill out onto the street, just within earshot of BART’s deafening roar. When I step off the train platform, I get a sense of a place that once was.

This street wasn’t always this desolate — in fact, the Seventh Street corridor was once the epicenter of cultural and economic happenings for Oakland’s Black community.

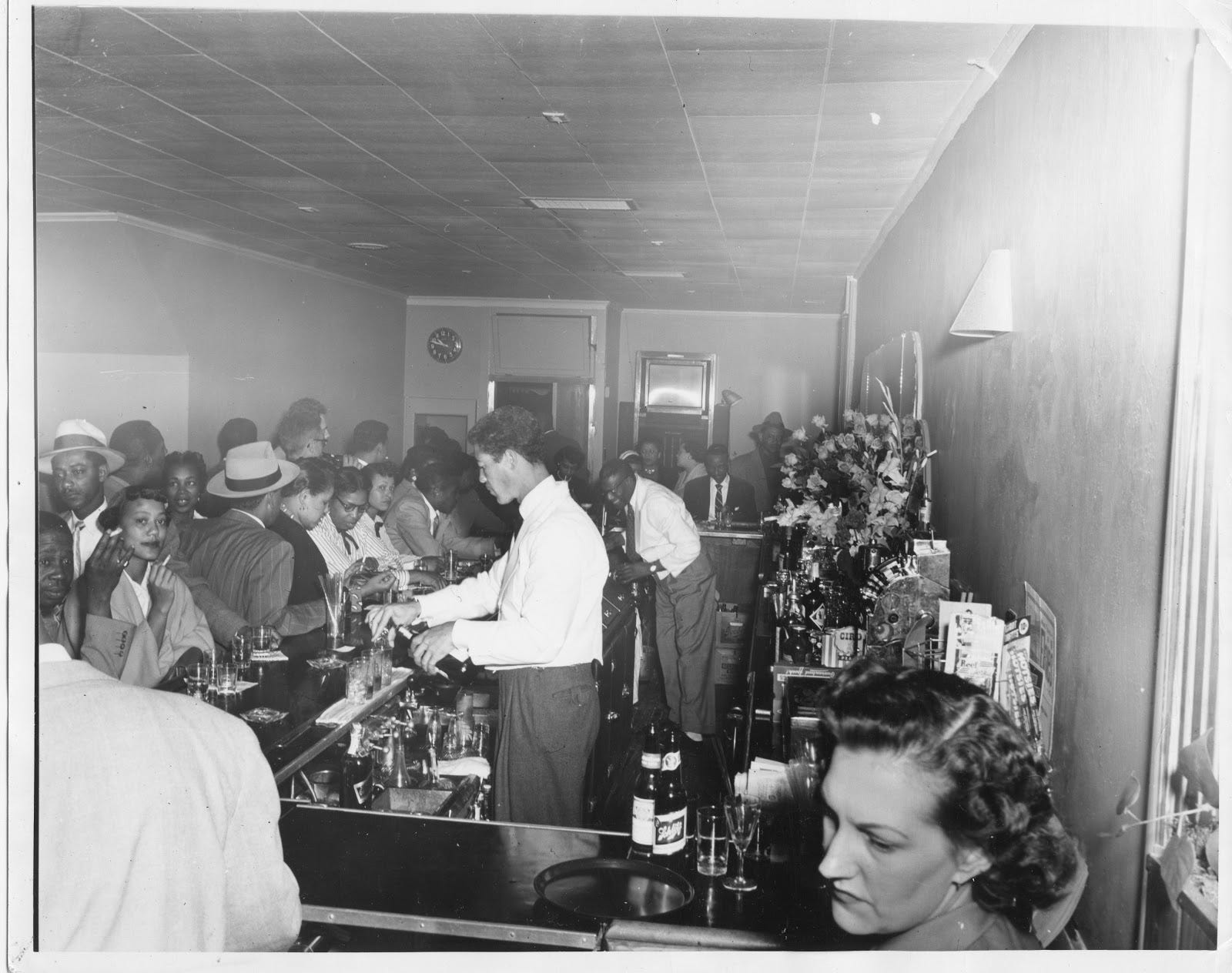

Known as the “Harlem of the West” in the 1940s and 1950s, Seventh Street operated as athrivingscene full of Black-owned jazz clubs, movie theaters, and soul food restaurants, contributing to a prosperous Black middle class.But post-World War II, dwindling jobs and divisive urban planning decisions thwarted the Black community’s success.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

Intrigued by its past, I took a look at historical records and talked with community members about what happened to the neighborhood’s once thriving environment and where it stands today.

The early days

West Oakland first gained momentum in 1869, shortly after the completion of the transcontinental railroad, and became a suburban outpost for San Francisco. Subsequently, this provided an abundance of blue-collar jobs ranging from delivery and laundry work to engineering. As the wartime industry rapidly grew, by 1911, West Oakland became a thriving economic sector and beacon for Black people migrating from the South, and was referred to as the “Plymouth Rock from the South.”

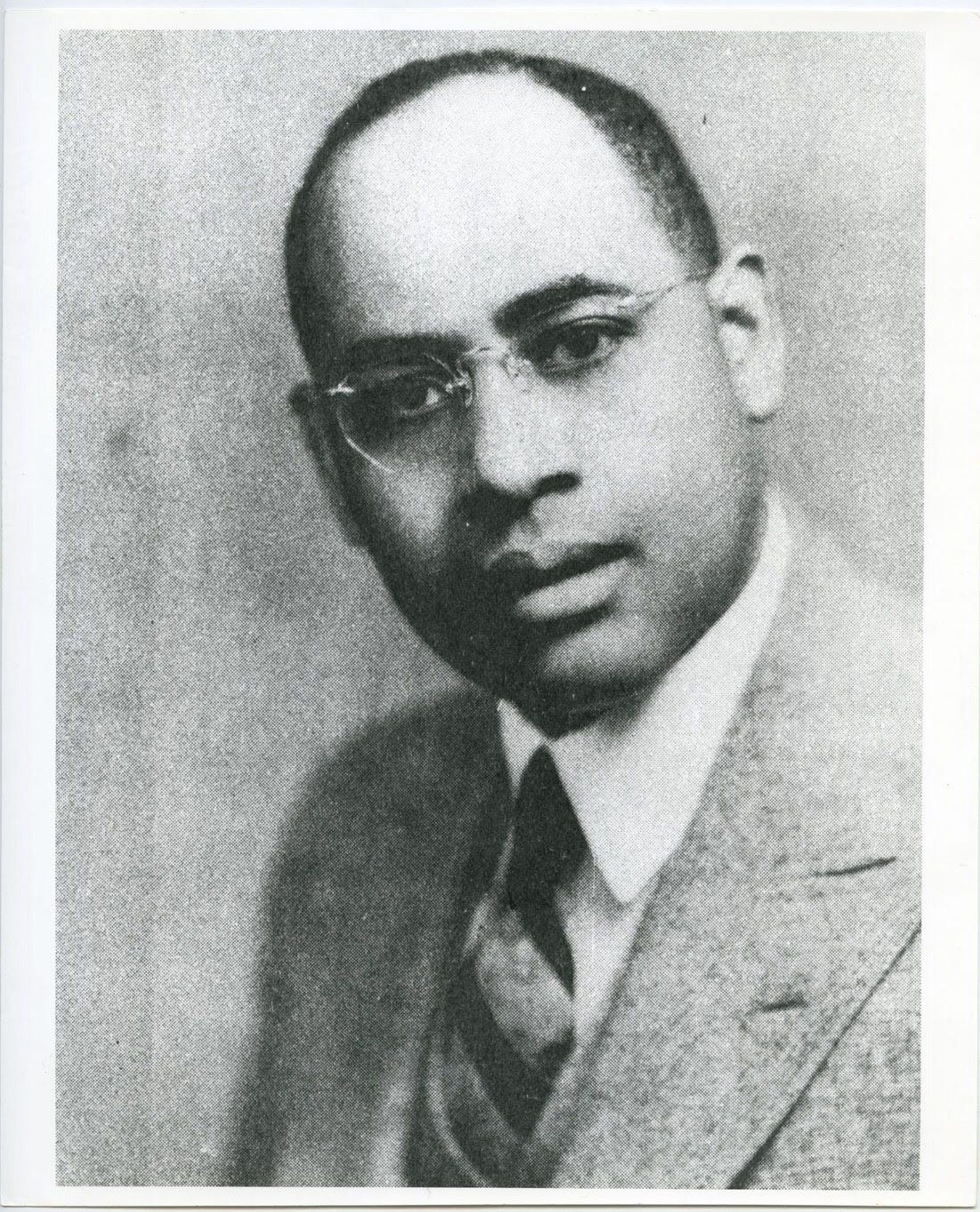

“When World War II began, West Oakland became the major point of entry for Black people coming in from the South, who came in to take advantage of the economic expansion and opportunities of the war economy,” Oakland native and former Oakland Mayor Ronald V. Dellums said a 2008 interview with UC Berkeley. From 1940–1945, the Black population exploded from around 8,000 to more than 21,000. “As a result of that, suddenly West Oakland overnight becomes a small Southern town.”

West Oakland’s prosperity also led to the development of renowned jazz clubs like Esther’s Orbit Room and Slim Jenkins Supper Club on Seventh Street. According to the Los Angeles Times, the strip’s myriad jazz and blues clubs were funded by a man named Raincoat Jones: a “gambling philanthropist” who allegedly earned the title because he wore a raincoat year-round that held concealed bottles of bootleg whiskey — and because “he refused to let a broke man go home without a raincoat if it was raining, or if he was hungry for food.”

Despite that he was frequently arrested for gambling — and that his cigar shop was raided by the police — Raincoat Jones brought in prominent musicians like Al Green, B.B. King, T-Bone Walker, Nat King Cole, and Ike and Tina Turner, among many other jazz and blues greats. In addition to jazz clubs, the neighborhood featured the Barn, a soul food restaurant in an actual barn, and the Lincoln Theater, a Black-owned movie theater where Billie Holiday frequently performed with her “mean little dog.”

“It was a beautiful place. I mean, there was a lot going on. There were all kinds of business. As I said before there were banks, cleaning, and pressing shops. You name it, and it was there,” Tom Nash, a musician and former Slim Jenkins regular, said in 1994 in an interview series documenting West Oakland history.

However, the good times didn’t last. When WWII was over and the temporary jobs dried up, the residents who fueled the economy — and contributed to the area’s thriving cultural scene — left too. As a result, the neighborhood deteriorated.

West Oakland, which was overcrowded with now-jobless workers, fell into disrepair. As crime and violence increased, Oakland officials labeled the neighborhood a “slum” and a “blight,” ultimately deciding to “redevelop” the area. Under the Housing Act of 1949, and through eminent domain — which gives governments the right to expropriate private property for public use — dozens of Black-owned homes and businesses were destroyed.

A series of urban planning decisions continued to devastate the Black community. In 1955, the construction of the highway leading to the Bay Bridge — the Cypress Freeway — cut through West Oakland, displacing swaths of Black families. “They came through and just wiped that housing out,” said economic development consultant Landon Williams in a KQED documentary. The deafening howl of the West Oakland BART station, too, “killed Seventh Street” and deterred anyone from walking around or performing in the area.

Ultimately, the city’s decision to “redevelop” West Oakland post-WWII had profound consequences on the Black community. This period of “urban renewal” during the 1960s and 1970s shuttered more than 800 businesses, demolished 2,500 Victorian homes, and displaced nearly 5,000 households. In 1960 alone, 500 homes were razed to make way for the U.S. Postal Service Distribution Center. “[T]he city…scattered the people. All of the Blacks, at that time it was almost 100% Black in the West Oakland area. Scattered them,” Nash said.

With these cruel and devastating decisions, federal urban planners sought to combat the Civil Rights Movement — and intentionally disperse the Black community, said District 3 Representative Lynette McElhaney, who’s been representing West Oakland since 2013.

“It was slightly less devastating than the destruction of Black Wall Street. But it was no less destructive,” McElhaney says.

Years later, West Oakland is still feeling the pain from state and federal decisions to displace — and segregate — the Black middle class.

Eventually, in 1962, Slim Jenkins was razed, and Esther’s Orbit Room — a once-thriving jazz club — became a small, neighborhood dive bar lovingly known as “the Grand Lady of Seventh Street.” It officially closed its doors in 2010, and the owner, Esther Mabry, who bought the building with her husband in 1959, died shortly afterward at the age of 90.

‘We’re fighting for the future and soul of West Oakland right now’

Officials have long discussed revitalizing West Oakland, in the past recommending a new commercial center with plazas, artisans, restaurants, shops, and entertainment.

McElhaney hopes the area will head in this direction to give residents a relief from poverty. She says the ability to earn living wages and own enterprise would help resolve economic and environmental inequities, noting that local organizations are coming together to address these issues, including non-profits like Community Foods and the Mandela Grocery Cooperative addressing food security and Attitudinal Healing Connection, which works to end cycles of violence through racial healing circles and art and literacy programs.

“West Oakland is a very resilient community,” she says. David Peters, a third-generation West Oakland resident, is part of a city-funded neighborhood association called West Oakland Neighbors (every neighborhood in Oakland has one, he says). Over the years, the demographics of his neighborhood have shifted, and while he’s seeing growth in his community, the future of the area is still uncertain.

His neighborhood — which was redlined — was 100% Black when he was a child in the 1960s. Now, he says, there are only about four Black households on the block. He is aware of the lofty redevelopment plans for West Oakland’s Seventh Street, but remains skeptical.

“When that gets built, who does it cater to?” he says. “This is the struggle. We’re fighting for the future and soul of West Oakland right now… We’re fighting to maintain, preserve, and document the Black migrant culture of people like my grandparents and their cohorts who came from Texas and Louisiana.”

McElhaney said federal and state partners must be “as intentional about community restoration as they have been about funding its destruction.” And while there are passionate, grassroots-led organizations leading the way to a brighter future in West Oakland, it needs to be uplifted even more. It’s a resilient, tight-knit, and culturally rich community that has withstood decades of oppressive white systems, and it deserves recognition, healing, and support.

You can help make that change. Here are local West Oakland organizations you can donate to directly: