For most, tiny homes are the stuff of HGTV — tricked out with modern amenities and plopped in a cute rural location where trendy hipsters take on a “simpler life.” But these little houses aren’t just Pinterest-worthy cabins—they’ve become a viable solution for the homeless across California and the country.

Using them to house the homeless in San Francisco has been talked about for years but has resulted in little to no action. Meanwhile, cities like Seattle and Austin have successfully tested and implemented these tiny-home communities, and our neighbors in San Jose and Oakland (though their projects are far from perfect) are also trying it out.

So why won’t San Francisco?

The reasons, though numerous and varied, come down to two factors: long-term solutions and unionized workers.

So far, city officials have brushed off the idea of tiny homes because they don’t consider them a long-term solution. This permanent-housing mindset — focused on building a mix of more low-income housing, shelters and navigation centers — makes sense, but it’s clear that it won’t happen overnight. Far from it. And in the meantime, thousands are still on the streets.

The homes provide a quick solution to taking people off the streets and into a community with supportive services, all while taking advantage of underused city land until proposed developments pass hurdles.

It’s true that the kind of tiny homes constructed for homeless individuals aren’t meant to last forever (nor are they HGTV cute). But they could still be an interim solution.

As the city allocates Prop C money and designs a grand plan for the near future, advocates of tiny homes argue that they could act as transitional housing on the way to something else. After all, the homes provide a quick solution to taking people off the streets and into a community with supportive services, all while taking advantage of underused city land until proposed developments pass hurdles.

“Tiny homes shouldn’t be the final place where [homeless people] move. We should be moving them into permanent homes,” said Kristy Wang, community planning policy director for the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR). “But right now, there’s certainly a need for more of that bridge housing. If that’s a possible path to getting everything developed faster, then that makes a lot of sense.”

But there’s another reason the projects have been blocked so far from SF—one you’ll hear about less often but that makes a whole lot more sense when you’re considering good ol’ politics: Local contractors, carpenters and the like want any sort of building to be done in SF, locally, by them. Tiny homes and modular housing, however, are often built overseas in places like China at a much cheaper cost and then installed wherever the units are shipped.

This is really part of a larger, circular issue — the local laborers rightfully demand a much higher living wage to be able to afford residing here, which makes companies unable to afford to hire them and deliver a cheap product for the city. It’s a dizzying catch-22.

That’s why, so far, little is happening in SF when it comes to tiny houses. It has been tried at least once with the St. Francis Homelessness Project, led by former mayoral candidate Amy Farah Weiss, who ran a pilot project from July 2017 to July 2018. On underutilized land in the Mission, behind coworking space Impact Hub, the project housed a former encampment resident who exited from a navigation center in 2015 without housing. The individual met with the organization and neighborhood members once a week and was given access to storage, bathroom facilities and the internet.

“It’s time to do something different. Whatever it is that’s the cause of the homelessness, every single person should have a safe place to be while they’re transitioning to something more stable that has reasonable agreements.”

The pilot ended, the person is back on the streets, and these structures from St. Francis now sit in storage. It infuriates Weiss so much that she recently sent the structures up to Chico, where two of this year’s fire victims could actually use them.

“I don’t accept that street homelessness is something we can’t figure out,” Weiss said. “It’s time to do something different. Whatever it is that’s the cause of the homelessness, every single person should have a safe place to be while they’re transitioning to something more stable that has reasonable agreements.”

One development company, Panoramic Interests, has been advocating for the city to give their version of tiny homes a try to little avail. Owner Patrick Kennedy pitched his vision of affordable housing—apartments that are modular and can stack on top of each other to fit more in one location—to SF officials in 2015. But officials denied it, as the project would involve units being built overseas (though assembled here by local workers).

“The problem with the tiny-home thing is you just can’t get the density,” Kennedy said. “Vacant land in cities is too valuable to put one-story buildings on. It’s not a long-term solution.”

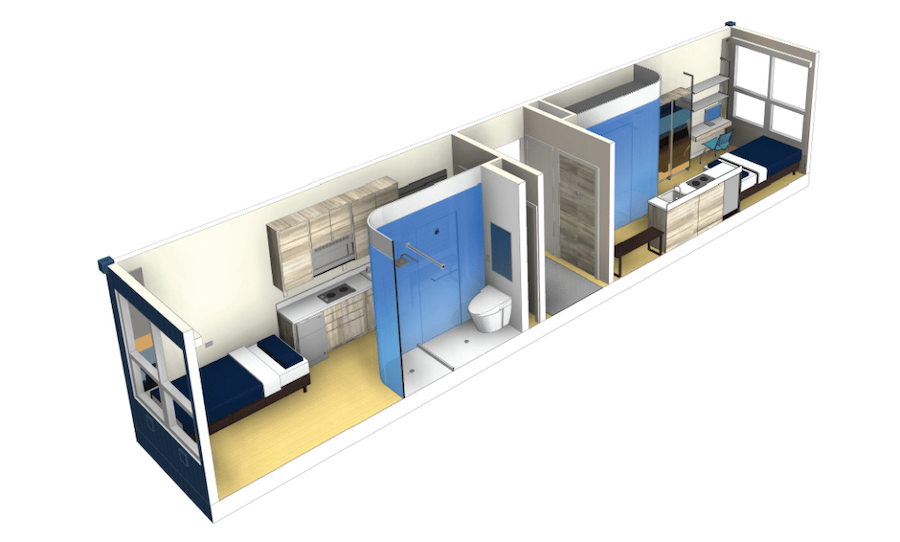

The company’s “MicroPADs” (“PAD” meaning “prefabricated affordable dwelling”) are 160-square-foot apartments, fully furnished with a private bathroom, armoire, desk and bed. These small apartments can be built in a mere four weeks in China and then shipped, assembled and stacked to build an apartment building that would normally take two years to construct, he said.

He plans to pitch the city on yet another plan this year using repurposed shipping containers designed as a modern version of the single-residence-occupancy unit with a common kitchen and bathroom. A 6,000-square-foot site (one piece of land the size of a single-family home) could house 24–48 people in their own units, he said. But even if this were to be built, much of San Francisco land is zoned for single-family homes only, which could cause a glitch.

“San Francisco has always told us they don’t want prefab,” Kennedy said. “I am hopeful that once we build one of these apartment buildings in the East Bay and show that the price is a fraction of what the current plans are, that the city will come around.”

Just last month, San Jose established a partnership with the nonprofit HomeFirst and Habitat for Humanity East Bay / Silicon Valley to develop two communities of tiny homes. They hope to be open by the summer to house around 320 individuals.

And Oakland debuted their first Tuff Shed village in January 2018, even though it was met with resistance and controversy. They introduced another in May under I-980 and yet another in October. Of the 126 people who have lived in these structures thus far, 39 have now found permanent housing, according to Oakland officials.

Other cities across the country are setting national examples. In Austin, nonprofit Mobile Loaves & Fishes is working with the city on a 10-year plan to mitigate homelessness, partly through Community First! Village. The initial phase of the project, which debuted in 2014, is today a 24-acre community with 120 micro-homes, 100 RVs and 20 canvas-sided cottages, as well as gardens, dining areas, medical and support services, WiFi, an outdoor movie theater and a bus line.

Seattle is another city experimenting with the solution, with nine operating villages and a total of 328 units. The villages include access to showers, restrooms, laundry facilities, a community kitchen and professional supportive services.

That’s not to say that some of these villages haven’t had challenges, but they’ve also seen success.

Whether it’s tiny homes or high-density modular housing or just plain building, San Francisco must find some sort of solution—quickly.