By Annetta Black

Bird watchers are patient people. They know all of the best spots to look for, and the habits of the birds in question. They know the best time of day and the last known roosting spots of their favorites. But sometimes the birds just don’t cooperate.

I’m not sure I have the right temperament for bird watching.

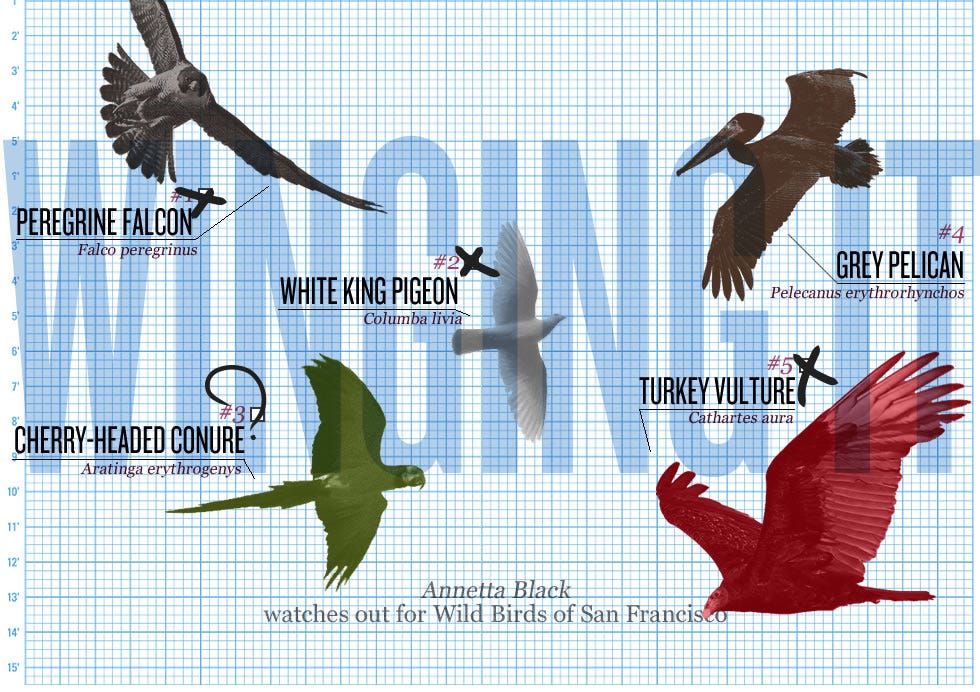

San Francisco, by all accounts, is chock-full of wild birds, and I don’t just mean the pigeons dirtying up Washington Square. Hundreds of exotic red-headed parrots call the city home, dodging the predations of the native red-tailed hawk, and the newly strengthened number of once-endangered peregrine falcons who live downtown.

Then there are the water birds — gulls and pelicans, ducks and cormorants. Even the pigeons hve a notable entry — the white king pigeon. Unlike their scrappy grey brethren, the Kings are delicate, breasty birds raised for food and unfit for survival on the mean streets.

Other than the seagulls and the scruffy-variety pigeon, I had never seen any of these in our city. So I met up with some people who could help me learn how to spot them.

First, I sought out Glenn Nevill, an extraordinary avian photographer who maintains a website full of near-daily photo shoots with a special focus on the peregrines. He is a dedicated amateur, shooting on lunch breaks and days off, but his photos are the stuff of National Geographic spreads. He seemed like the right guy to show me a falcon.

We met at the head of Market Street on a busy weekday noon, and headed for the waterfront immediately. Glenn was toting a serious camera bag along with a scope on a tripod. We headed to Pier 4, and set up the scope.

The story of the peregrines in the Bay Area is a resounding success. In the early 1970s, three decades worth of DDT had reduced the California population to just two breeding pairs, with no birds at all seen east of the Mississippi. Largely due to local efforts, in 1999 peregrines were removed from the National Endangered Species List.

In our city, there are a few places to look for peregrines. The PG&E headquarters building downtown has a nesting box built specially into an upper floor terrace. In the springtime, nesting birds can be seen flying to and from. The other place to look was where we had the scope aimed: W4, the massive central pillar of the San Francisco side of the Bay Bridge. Through Glenn’s high-powered scope we were just able to make out a little black bird butt on a maintenance walkway below the bridge.

This was the bird butt of none other than Dapper Dan, the city’s current resident male. His companion Diamond Lil must have been elsewhere. Glenn has been photographing the pair since they took the space formerly occupied by the well-loved pair George and Gracie, who had been in residence since 2002. Dan and Lil had three fledgelings this spring, named Hi, Liwa, and Kiwel, further adding to the state’s population which numbers approximately 800 individuals.

In the foreground, another recently endangered predator put on a better show. Grey pelicans swooped and dove in the waters by the pier. Now a common site around the Bay Area, they were once the poster children of the Endangered Species Act. Another victim of DDT-thinned eggs, they were only removed from the list in November of this year.

We finally snapped a couple shots of the pelican’s dramatic dive in action, and got a few extra pictures of gulls and grebes in the meantime.

Armed with my camera and a pair of crappy binoculars I made for the Marin Headlands, where the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory holds daily noontime bird counting sessions on Hawk Hill. I arrived a bit early, but about a dozen volunteers had beat me there. Most came armed with impressive binoculars or scopes set up on tripods. I jockeyed for a spot and tried to pretend I knew what was going on.

As the noon siren rang out across the Bay, they began the count. Members of the Observatory and volunteers would spot a bird, identify it and call it out. An Observatory member noted all of the sightings in a contractor’s binder.

Mostly out of range of my lenses, or lost against a background of bird-colored hills, I had trouble keeping up. Finally, I tracked a shadow across the landscape and saw a majestic winged creature soar up above the horizon. I snapped pictures frantically, wondering what it might be, until someone called out: “And we’ve got another turkey vulture.”

As I got the hang of it, I began to see some of what they were seeing. Their helpful bird profile chart, designed for visiting schoolchildren, aided me. In just an hour I was able to spot two red-tailed hawks cruising past the Golden Gate Bridge, a pair of big black ravens who flew past and then settled on a rock nearby, a circling merlin (a smaller falcon), a smattering of unidentified songbirds and a whole bunch more turkey vultures.

As the afternoon began to fade, I headed for Coit Tower. I parked and walked the ring of steps that surround the tower, scanning the trees and the nearby rooftops, listening for the rustle of feathers or their distinctive squawks. All was quiet, except for the chatter of tourists admiring the beginnings of sunset in French, Japanese, and something that might have been Russian. I looked closer, trying to distinguish tails from leaves, watching for any signs of birdy motion.

No one knows exactly where our parrots came from, but the most common bird, the Cherry-headed Conure, originates from Ecuador, making it most likely that our flock comes from escapees of an early exotic pet craze. They don’t actually live on Telegraph Hill, they just come here to graze, but online a lot of people had mentioned recent sightings at dusk, so it seemed like a good bet.

As I paced, the light faded and the sunset burned orange on the horizon, back lighting the Golden Gate Bridge, and I realized not for the first time that sometimes the tourists get the best view of our city.

The observation deck in the tower closed, and they pulled the industrial grate closed. Still no birds. Finally, the last glow faded from the sky and the park was quiet. Just me and that big creepy statue of Christopher Columbus. No tourists. No parrots.

For now, the parrots of Telegraph Hill are keeping their secrets from me. But I’ll be watching. I’m onto them, and it’s only a matter of time.

In Elizabeth Young’s Bayview backyard, a dozen or so white pigeons were softly cooing and sitting on wooden eggs. As we approached the coop with seed, one of them was messily taking a bath in a container of water by the door, while the others were generally just hanging out in nesting boxes or perches. They seemed utterly unperturbed about our entrance to their territory.

Elizabeth describes herself as an accidental pigeon rescuer. She began volunteering at the San Francisco Animal Care and Control (SFACC) two years ago, and learned for the first time about the plight of urban King Pigeons. These birds, known as Utility Kings, are a bigger, snow white version of the common grey feral pigeon, and are raised and sold for food at live animal markets, primarily in Chinatown.

Bred for tasty breast meat, these are not natural survivors. Feral pigeons are mighty little flyers, hitting speeds of 60 mph, while these guys, encumbered by their unnatural bodies, flap heartily to reach a much slower speed. Easily picked off by hawks and falcons, as well as dogs (and cars), they are essentially snack pigeons.

They are also beautiful, soft spoken, and gentle-natured. As Elizabeth found out when she started volunteering, Kings end up in the shelter nearly every week, and until recently there was nowhere for them to go. She realized that all of the animals had support organizations, except the pigeons. So she started one.

Both of us being meat eaters, it is uncomfortable to reconcile the plight of an individual animal, currently three inches from my face and nibbling on my hair, with the knowledge of the chicken breasts in my fridge at home. It’s complicated, and very American. As Elizabeth puts it, “It’s a ridiculous cause, but it matters to them. They want to live.”

After my visit with Elizabeth, I went to the SFACC to see the current crop of potential adoptees. I was happy to discover that at least on this day all of the birds at the shelter had been successfully adopted out, making my final birdwatching mission a happy visit to empty cages.

Designed by Gordon Baty

Bird pics courtesy of