Two hundred fifty years ago, in the mid-1700s, there were at least 10,000 indigenous people coexisting in about 40 distinct tribelets on the land between Big Sur and the San Francisco Bay Area. They lived, as they had for thousands of years, amid a now-extinct reality of dizzying abundance: vast marshes and lush meadows, wild salmon in the rivers, breaching whales in the bay and even grizzly bears in the endless oak forests. The San Francisco peninsula was a barren sweep of coastal grass and sand dunes, and only a handful of European sailors had ever made anchor on the shore. The local tribelets went by various names and spoke dozens of unique languages, but today we group them together as “Ohlone” because this name rings most true for many of the surviving descendants.

The Ohlone were skilled hunter-gatherers and masterful artisans living in villages that were perhaps five to ten miles apart. Some of their norms might shock the modern inhabitants of the region — they spent much of their time naked, ate bear cubs and baby seals, and generally took whatever they wanted from the natural world—but their world was so fruitful and their population so small that they maintained a healthy, sustainable carrying capacity in spite of their opportunistic habits.

The process begins with a simple acknowledgement: if you live in the Bay Area, then you are living on Ohlone land.

The Ohlone did not conceive of themselves as separate from their environment—or beyond it—but rather inextricable from it. Indeed, the Ohlone were immersed in an animistic world in which every creature had significance; individual trees and stones had names; and the magic of creation was as present and alive as the Pacific sea breeze.

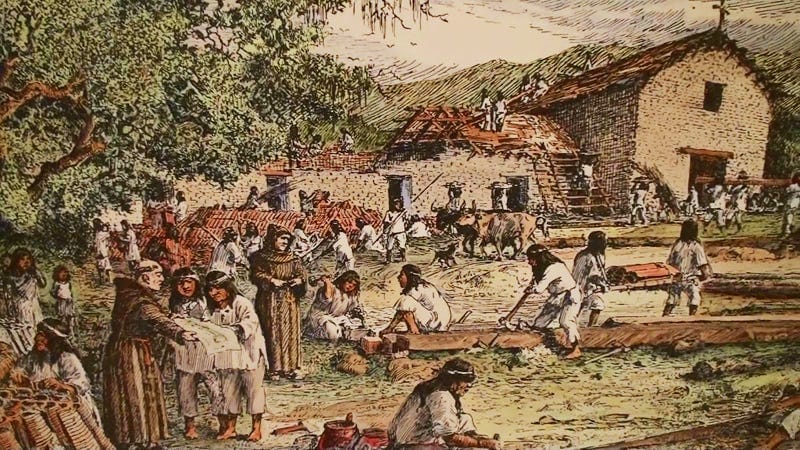

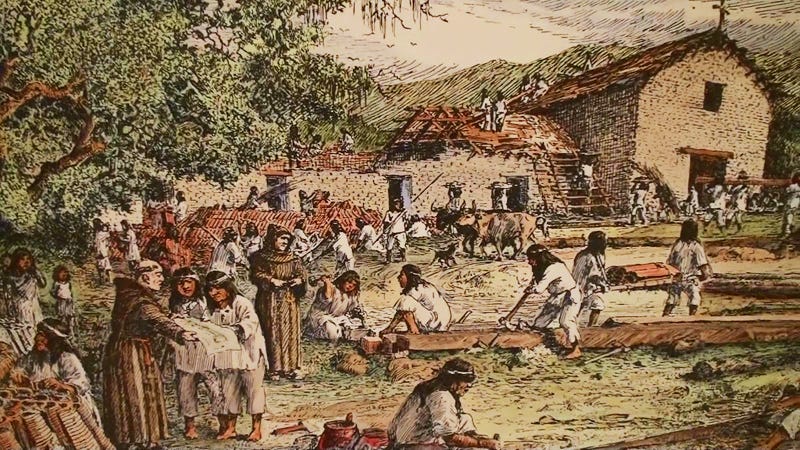

Almost all of the Ohlone died of disease, despondency and malnutrition in the catastrophic decades following the Franciscan fathers’ establishment of the California missions. The survivors were forced into labor and spiritual bondage, and their heritage was all but snuffed out by the steamroller of cultural imperialism. Today, their Bay Area is nearly unrecognizable, paved over and densely populated by non-native humans from all over the world. As inheritors of this land, it is our responsibility to recognize and absorb the rich depth of its pre-European history.

The process begins with a simple acknowledgement: if you live in the Bay Area, then you are living on Ohlone land.

If you are like me, you were born in the suburbs of Silicon Valley to parents who moved here and met here with no ancestral ties to the region. You learned about the Ohlone in elementary school, and perhaps you visited the old Spanish missions where many of these people lived out their final days in captivity. You knew that they harvested acorns, wove baskets and built shell mounds. You knew that they all but disappeared under Spanish occupation. However, you probably didn’t learn much about who these people really were: their dreams, their customs and their relationship with the land. You encountered their culture only within the context of its destruction.

If you were born elsewhere and moved to California as an adult, then you may have never even heard of the Ohlone. Your understanding of local history may well begin with the 1849 California Gold Rush and the influx of prospectors who built the foundations of modern San Francisco.

Embroiled within our insatiable modern beehive of concrete, glass and asphalt, we can find it difficult to imagine that the Bay Area was ever anything other than a cosmopolitan hub of social and technological progressivism. Call it the amnesia of modernity or the Eurocentric myopia of Manifest Destiny. The crux is that it is all too easy to come of age in 21st-century California with a tragically weak understanding of what this part of the world was like only 300 years ago.

We 21st-century Bay Area dwellers are not to blame for the crimes of the past. Certainly, the California missions — like the statues of Confederate generals that have lately provoked such controversy in the American South — stand as monuments to abhorrent acts of cultural imperialism and forced labor. Most of the massive “shell mounds” that once marked the locations of old Ohlone villages have been dismantled to make way for modern development — and local indigenous activists have fought this development to little avail. Yet we cannot undo the obliteration of a way of life, nor can we turn back the tide of globalization.

We can mourn the displacement of the Ohlone, and in the same breath we can celebrate the continued public presence of Ohlone descendants who are working today to preserve and nourish their indigenous identity.

One-third of the Bay Area’s population was born outside the US, and less than one percent of locals identified as American Indian in the 2010 Bay Area Census. As a massively mobile world civilization, we are collectively redefining what it means to be “from” a place. I am a second-generation Californian because I was born in Palo Alto, but I have no deeper roots here than my parents, my history books or my relationship with the land. Are we place-less people, then, in a region that has forgotten its past? What does it say about our society that so many of us have no idea who lived here just three centuries ago?

I propose that learning about the Ohlone people and their world is an act of becoming more connected to the land that we live on. We cannot revive the past, but we can try to hold space for it in the present. We do not use the acorn as a staple food, but we can remember how the Ohlone did so in the not-so-distant past, and we can think about that heritage when we sit beneath an oak tree. Even a basic study of local history can give us a stronger sense of place. When we consider the people who came before us, we begin to consider how we’d like to be remembered by those will come after us.

In this cosmopolitan corner of a globalized world, perhaps heritage need not imply heredity. We can all, as Californians — no matter whether we are first- or second- or fifth-generation locals—acknowledge the legacy of the Ohlone people. We can mourn their displacement, and in the same breath we can celebrate the continued public presence of Ohlone descendants who are working today to preserve and nourish their indigenous identity. We are all here now, living on the land, and thus we are all inheritors of its past.