George Floyd’s murder and the ensuing protests have shook me. While I’m grateful to have all of my lovely non-Black friends checking in on me and asking how I’m doing, I’m also tired of pretending that I’m okay. Honestly, I’m not okay. These last few weeks have forced me to examine, once again, all of the ways in which I have been affected by racism in my life and on a daily basis.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best content about life in the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

To avoid having to explain these to everyone I know, I’m writing them down here — along with ways non-Black people can be part of the solution.

1. I have questioned my Black beauty.

The beauty industry profits from convincing us that we’re not good enough as we are, provoking us to buy something to alter our appearance. This is especially damaging to the Black community, because the beauty industry upholds Eurocentric standards — lighter skin, straighter hair, and bluer eyes, to name a few. The beauty industry has been so effective at pressuring us to mute what is naturally immutable that I wonder if there was ever a Black body who hasn’t compared themselves to white beauty standards. Admittedly, if you were to Google “hottest women,” perhaps Beyoncé or Rihanna would appear. But even famous Black women who are considered attractive are attractive in a “white” way. They may possess large eyes, a small nose with a high bridge, and relatively fair skin. We need representation of pure unfiltered Black beauty, both for people like me and for generations of Black kids to come.

Solution:

Media creators, commit to having dark-skinned, kinky-haired Black faces featured prominently in your next production. Media consumers, go out of your way to consume media created by Black people and demand that brands have enough representation.

2. As a Black author, publishers are less likely to amplify my voice.

The world of publishing is 79% white. Authors like me who desire to be traditionally published often need literary agents and/or an editor. Literary agents and editors are looking for what will become the next commercial success, which Black authors can translate to mean, “Will enough white people read this?” Our creative success depends on white people’s validation. In order to achieve this market success, so many mainstream books by Black authors are whitewashed, erasing powerful Black voices, characters, and lore.

Solution:

Non-Black literary agents and editors, commit to representing and elevating the unpublished, unagented Black creators. Everyone else, buy books by Black authors for yourself and your kids to demonstrate to publishers there is a demand for their content.

3. When I embrace my natural hair, the world treats me differently.

My hair is a political statement because there’s only one continent that produces curls that reach toward the heavens. Growing my hair out actually makes me more Black. It puts a target on my Blackness. It says, “Hey, I’m different.” And I know that people judge me for it. In 2019, I started growing out my hair. By the time it was long enough for cornrows, I began experiencing the judgment. Last December, after my consulting company’s holiday party, I went to a club with some of my co-workers. I was the only person that wasn’t allowed to enter. I was also the only Black person. After reading reviews on Google, I found that this establishment has a history of denying entry to Black men. The fact that I was clearly part of a well-dressed group of professionals wasn’t enough to overcome the club’s bias against my Black skin and natural hair.

Solution:

Businesses, create anti-discrimination policies and mechanisms for resolving situations in which a customer believes they’ve been discriminated against. Consumers, support brands that not only commit to respecting all human life, but also demand that they walk the walk. Also evaluate your own bias against people who look a certain way that may be different from you.

4. I’m often confused about when racism is happening and when it’s not.

What makes racism so insidious is that it frequently leaves me wondering, “Did they treat me that way because I’m Black?” That in and of itself takes a toll, especially when the answer is not clear. Yet it rattles me that we live in a world where the answer could be “yes.” “Did my doctor not spend enough time with me because I’m Black?” Well, maybe; doctors are 22% less likely to prescribe pain medication to Black patients than white patients. “Did I get passed over for promotion because I’m Black?” Well, maybe; Black men and women are less likely than any racial group to get promoted. Racism forces me to question what I experience and why, a process that is equal parts frustrating and exhausting.

Solution:

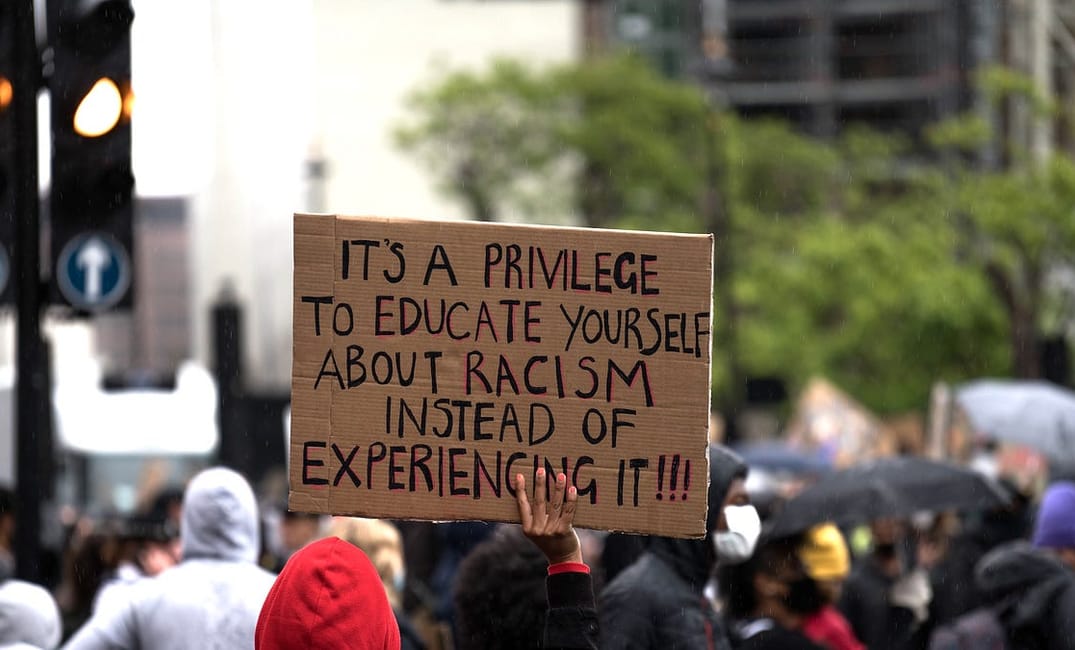

Non-Black people, learn about implicit bias and identify how it affects your everyday worldview. Then, work to address your bias. This is hard, deeply personal, lifelong work.

5. Intergenerational trauma stimulates my consciousness.

Not only am I shaped by the direct experiences I’ve faced, but because the people who raised me faced the same struggles. Growing up, there were so many rules I had to follow because my parents didn’t want me to face the discrimination they faced. Don’t eat a banana in public, they said. Someone will call you a monkey. Don’t eat watermelon and fried chicken in public. Someone will call you a pickaninny. Don’t gather with three or more other Black men wearing the same color. Someone will think you are in a gang. Don’t let a white man call you a “boy.” We don’t live in the Jim Crow era anymore; you are a man. And despite how much you want to save the world from single-use plastics, don’t walk out of a grocery store holding unbagged items. Someone will think you are stealing.

Solution:

Non-Black people, read memoirs by Black voices. Learn about their stories. You’ll become more conscious of how your lived experience is different from others and how you can become a better advocate for racial equity. A few I have enjoyed include What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker by Damon Young, How We Fight for Our Lives: A Memoir by Saeed Jones, and The Light of the World by Elizabeth Alexander.

6. Racism is so ubiquitous, I choose to not fight every battle.

Racism is so ingrained in our society that even Black people have some level of tolerance for it. We can’t fight every battle. While growing up in Georgia, I often witnessed Confederate flags tinted on the windows of pickup trucks. A symbol used to terrorize Black people for centuries, the Confederate flag continues to be weaponized against the Black community today. When people are so committed to racism that they’re willing to give up their rear-view visibility for it, how much are they going to listen to me?

Solution:

Non-Black people, read anti-racism literature so that you can stand up to the overt and subtle ways white people perpetuate racism in our society. Tim Wise, author of White Like Me, and Dr. Tina Harris, professor at the University of Georgia and co-author of Interracial Communication: Theory Into Practice, are a few of my favorites.

7. I have to witness my people getting hurt.

When Black people, my people, can’t vote, can’t birdwatch, can’t jog, can’t barbeque, and can’t breathe, I can’t ignore the very real fact that I could be them. I could have been Tamir Rice, Ahmaud Arbery, or any of the other countless, unarmed Black men who die at the hands of police officers.

Solution:

Non-Black people, don’t choose to be a bystander to the injustice happening in our world. March in solidarity with the Black community. Take out your phone and film police when you see them interacting with Black people. Use your platform — social media, yard signs, and clothing — to tell the world where you stand.

These suggestions don’t even begin to scratch the surface. Absent from this discussion is how 25% of my DNA comes from European colonizers, or how banks deliberately barred my grandma’s family from taking out a loan on their farm, intentionally stemming generational wealth, my wealth, years later. Nor, at the bottom of it all, how I stand at the intersection of both queer and Black identities and the complexity of this reckoning.

These are just a few reasons I’m not okay, but writing about it actually helps. And you doing something about it helps even more.