By Tienlon Ho

THIS STORY STARTED WITH AN AMUSE-BOUCHE THAT WAS NOT SO AMUSING AND NEVER CAME CLOSE TO MY MOUTH.

It was a Friday night out with friends at a crowded and well-regarded restaurant, the sort of place that grows everything itself or else buys its product locally, and gets written up so often in the culinary rags that you’ve probably eaten there.

The amuse arrived — a bite of lightly poached fish in olive oil. As I was admiring it, I noticed a brownish-red coil resting on top like a stray hair on a pink pillow. I pushed it aside thinking it was a piece of intestine.

Then, it moved.

It started stretching itself up through the oil, unfurling into a long, straight line, apparently trying to breathe. As the din of the restaurant in my ears made way for the pounding of my heart, I choked back a scream and waved frantically for our waitress.

Having worked prep in restaurants before, I had sympathy. You get stacks of boxes filled with stuff straight from the farm — almonds in their fuzzy shells, eggs slick with chicken poo, muddy leeks, pigs with hooves, all of which have to be thoroughly cleaned and broken down before any actual cooking begins. Sometimes restaurants, even those at the top of the heap, run into trouble regardless of how much care they put into things.

Having also had some experience with water ecology, I suggested to our waitress that the worm looked like a parasitic nematode, the kind that can eat a fish from the inside out.

An apologetic manager came by a while later to comp our meal and confirm my suspicion. “We get all our fish straight from the docks every morning, so we never freeze it,” he said. He described how the cooks painstakingly picked through the fish with tweezers. “Unfortunately, this is what happens when food is very fresh.”

That got me thinking. The Bay Area is the region that coined the phrase “farm to table.” It’s so fixated on eating organic, local, and seasonal that it hosts more than 40 farmers’ markets a week, and city governments have passed ordinances to make room for urban gardens so that we can all bring the farm to our own tables. But we may not be as connected to what we eat as we think we are.

In our obsession with getting our hands dirty, maybe we forgot what actually lives in the dirt. So in the spirit of facing the truth, here are a few things we’ve probably already swallowed:

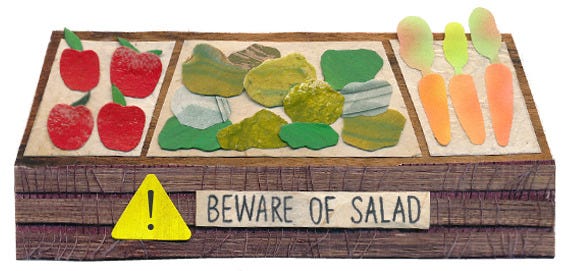

WORMS

Maybe you’ve noticed the garden-variety critter carving its way through an apple before you take a bite, and carefully removed it (or flung the apple out the window in a panic, as is my method). What you haven’t noticed are the nearly invisible, parasitic buggers — the roundworms, tapeworms, and flukes.

As the FDA warns, when eating raw and undercooked fish, including sushi, ceviche, cured salmon, and brined herring, you are at risk of ingesting parasites. Three in four wild salmon in the US are infected. In Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain admitted that most cooks give up swordfish after inevitable run-ins with three-foot-long worms. Once swallowed, most parasites can live for only a week or so in our digestive tracts, but there are rarer kinds that can live for years, causing anemia, nausea, and pain — especially if they swim their way to your heart.

Trichinella is the equivalent worm in land animals and, when consumed, causes similar symptoms plus unsightly bloating. The larvae sleep in protective shells embedded in your main course’s flesh until your stomach acids digest the shells and set the larvae free. Take comfort in the fact that roundworms are unlikely to be hiding in your pork chop or steak tartare — at least in the United States. Trichinella is most common in wild game here.

If this freaks you out, eat only cooked meat and cooked or previously deep-frozen fish. Fortunately, most sushi restaurants deep-freeze their fish, even when they say they haven’t. On the flip side, more and more cooks with bad technique (and worse, low-grade product) are trying sous-vide, a method that “cooks” proteins in water baths set to low, parasite-Jacuzzi temperatures.

Fecal Bacteria

Maybe you already swore off packaged salad greens after the E. coli outbreaks

in 2006, 2010, 2011, and 2012; the Salmonella scare in 2008 and 2011

; or the

2012 Listeria recall. Researchers suspect, however, that loose greens are harder

to trace back to their source, and thus connected less often to outbreaks of the

“stomach flu.” In other words, eating raw, loose-leaf greens is not necessarily safer

than eating raw greens that come in a bag.

On the farm, animals and fresh vegetables are normally kept far apart to prevent

contamination, but especially in today’s high-output farms, whenever there’s rain,

feces wash downhill and into irrigation ditches. Unfortunately, while careful washing

gets rid of 90 to 99 percent

of pathogens on lettuce, produce that soaks up tainted

water can never be washed clean. Cook your vegetables unless you know you can

trust them. Skip raw sprouts, which are often grown in warm, wet conditions rife with

bacteria. Or be ready to pay the toll, which, for most of us, is a night spent sleeping

by the toilet.

mushed-up mice

Have you ever seen grapes harvested for wine making? Probably not, because someone would have had to explain what happens to the mice, beetles, snakes, and caterpillars that fall in with the fruit. Most of this “material other than grapes” (MOG) gets sorted out by hand, especially when fragile, expensive varietals like Pinots are involved. Stringent vintners use grapes with no more than 1 to 3 percent MOG to avoid tainting the flavor, but some are less picky. More MOG often correlates to a cheaper price. Rest easy, though — the wine press and alcohol will kill off whatever needs killing.

carcinogenic molds

Common molds like Penicillium and Aspergillus float around in the air, but in high-

enough concentrations they produce mycotoxins, which weaken the immune system,

and may cause cancer and lung diseases. These molds are found in everything from

peanut butter to the soft apple on your counter to the furry coat on that old hunk of salami

under the refrigerator. They can also form in large clusters on the surface of kombucha

(home-brewed or store-bought) that’s left to linger too long, turning the healthy symbiotic

community of bacteria and yeast into a black shag carpet of mold. The lesson: don’t eat

things that grow hair where there wasn’t hair before.

diesel fuel and dog pee

When you look down at a plate of “foraged” greens and wild mushrooms artfully arranged to look like spring flowers blooming in soil, it’s easy to forget that “foraged” means, at best, plucked from someone’s garden and, at worst, picked in the park. Done wrong, your fancy salad has notes of weed killer, exhaust, and dog pee.

The first rule of thumb is to always harvest at least 50 feet away from roads and far enough off trails to avoid spray (of the dog and herbicide kind). The second is to leave enough to grow back. The third is to wash what you drag in really well. If you don’t trust the folks who hunted down your food, just don’t eat it.

everything else

If, perchance, what you just read has inspired you to start a table-far-from-the-farm

movement and switch entirely to processed foods, you might be interested to know

that the FDA officially sympathizes with how hard it is “to grow, harvest, or process

raw products that are totally free of non-hazardous, naturally occurring, unavoidable

defects” and makes allowances for things such as rat hairs, rodent poop, and “pus

pockets” in packaged foods.

In fact, the FDA allows for a maximum of 30 fly eggs (or 15 fly eggs and one maggot)

in the tomato sauce on that pizza you were just considering. According to the FDA, any

more than that would be “offensive to the senses.”

So maybe you’re wondering if I will ever go back to the restaurant that served me a worm.

I can tell you, definitively, yes. Even if eating farm-to-table means sometimes eating

the farm, I’m all for it. I swallow more bugs riding my bike. And the pork dish that came

after the fish was ridiculous.