In no way, shape, or form am I considered the ideal prospective homeowner. I’m mired in student loan debt, addicted to Depop, and occasionally use a credit card to “go all out” and order Chinese food. It’s safe to say that I won’t be able to take out a mortgage anytime soon. But whether I live in a single room occupancy in the Tenderloin I just moved out of or the studio in West Oakland I just moved into, I consider the Bay Area my home — and it doesn’t hurt to dream. That’s why one afternoon, I pulled up Zillow, aka Craigslist for grown-ups, to see what was out there.

As I applied my low-price filter for homes under $375,000, I wondered, do I even stand a chance in the Bay Area housing market? What type of place could I get in Oakland for the amount of rent that I’m paying for my studio? Unsurprisingly, not many.

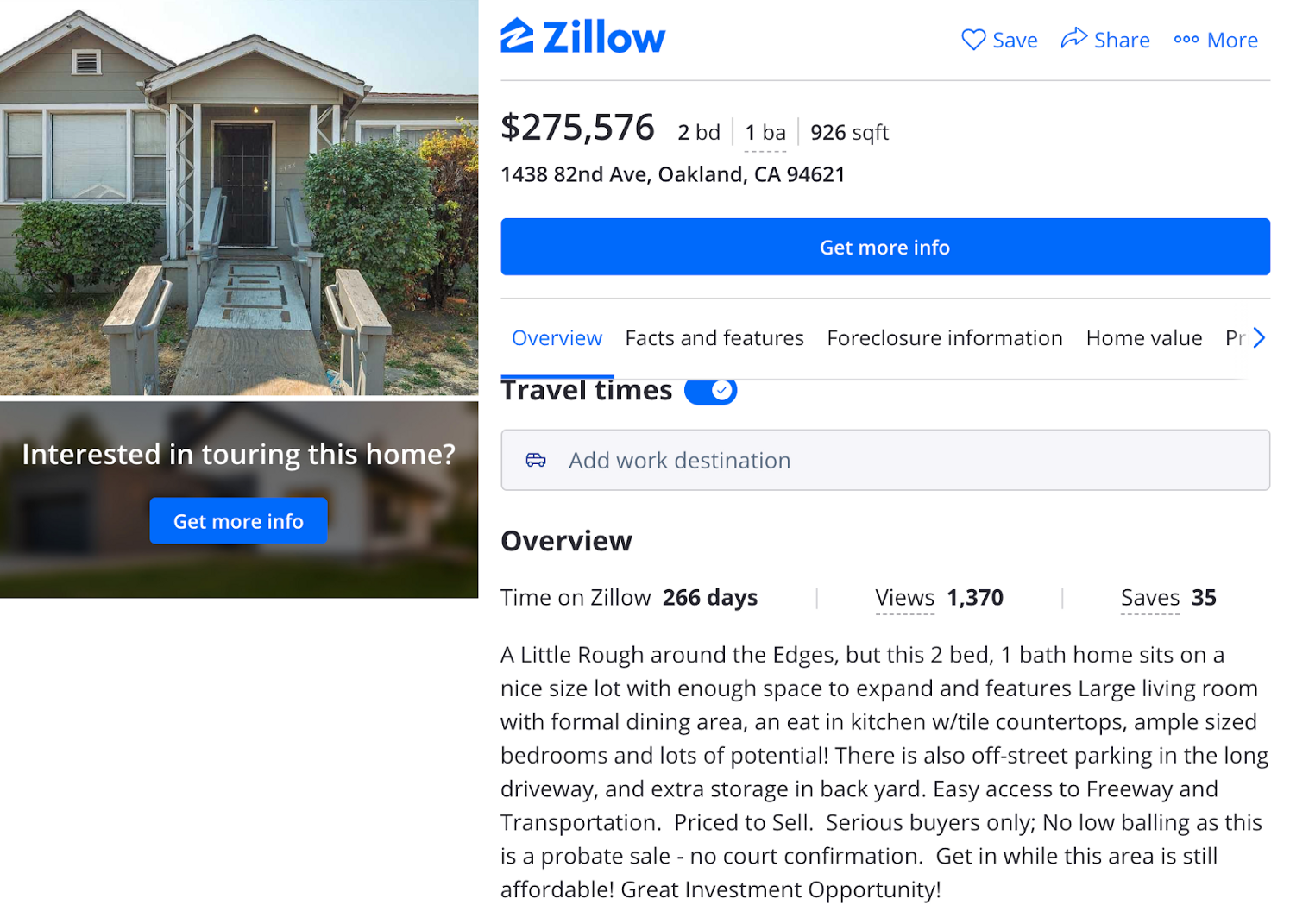

In total, I got less than 30 results back, all of which directed me to houses in East Oakland. There was the obligatory dubious live-work space (“a must-see!”) and a dilapidated shack on an empty lot (“The possibilities are limitless!”). Most of these homes were concentrated in Coliseum and Eastmont, historic areas which saw the birth of sideshows and hyphy rap, movements which are considered integral to Oakland culture. However, I also noticed that nearly half of the homes available were foreclosed — meaning their original owners were unable to keep up with their mortgage payments, resulting in the houses being auctioned off by lenders.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

Imbued with borderline predatory language, posts on these foreclosed houses urge potential buyers to “get in while this area is still affordable” and view it as an “investment opportunity.” In the East Oakland neighborhoods with these foreclosed homes up for auction, around 40% of the population live below the poverty line, according to Zipatlas, which collects demographic information based on zip codes.

My current neighborhood of West Oakland has an equally high percentage of residents living in poverty, making both of these districts arguably the poorest in the city of Oakland. And according to Census.com, the zip codes that have most of these foreclosed homes have prominent Black and Latino populations.

I soon discovered that while the homes in my price range are considered “affordable,” their availability likely came at a cost.

Predatory lending

This summer, the San Francisco Chronicle reported the city of Oakland is now authorized to sue Wells Fargo over the company’s “predatory” home loan practices, which allegedly targeted minority borrowers dating back to 2015. According to the Chronicle, Wells Fargo issued riskier, high-cost loans to Black and Latino borrowers without allowing them to refinance. Minority borrowers were twice as likely to receive these types of predatory loans compared to white residents.

“Wells Fargo was 2.4 times as likely to make loans to Black borrowers on those terms, and 2.5 times as likely to Latinos, as it was to white, non-Latino households,” the Chronicle reported.

Additionally, 14.1% of these Wells Fargo predatory home loans ended in foreclosure, while only 3.3% of homes ended in foreclosure in nonminority neighborhoods. According to Judge Mary Murguia of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, the lawsuit from the city of Oakland “plausibly alleged predatory loans to Black and Latino borrowers necessarily resulted in widespread foreclosures, which in turn necessarily reduced property values, and thus necessarily reduced Oakland’s property-tax revenues.”

Now, Oakland is able to at least seek damages for property devaluation, which it says may amount to $50 billion. Individual borrowers can also file their own separate lawsuits, as long as it’s within two years of them taking out a loan.

In a statement, Oakland City Attorney Barbara Parker, said “Wells Fargo’s racially discriminatory mortgage lending practices against African Americans and Hispanics have devastated individuals, families, and communities in Oakland, throughout California, and across the country where Wells Fargo operates, dramatically increasing foreclosures and decreasing the Black and Latino middle class.”

However, Wells Fargo has denied that they participated in predatory loan practices, and “are prepared to present strong arguments in support of our long history of fair and responsible lending in Oakland and across the country.” In her opinion issued in August, Judge Murguia wrote that Oakland’s complaint was sufficient in arguing that it received reduced property tax revenues due to Wells Fargo’s discriminatory lending practices.

Corporate landlords

Cat, who volunteers for the SMC Tenants Council — a local tenant union that organizes actions specifically against Sullivan Management Company, a major corporate landlord — says that such landlords have a history of capitalizing on foreclosed homes in Oakland. SMC, which rents out properties in Oakland, Berkeley, and Emeryville, bought nearly 350 properties during the 2008 financial crisis.

“SMC basically came to West Oakland, snatched up hundreds of foreclosed houses for super cheap, and rented them out to tenants at high prices. It’s really frustrating since they do a poor job,” Cat says.

Tenants have been dealing with mold, rats, and other vermin. “We have people who are living in conditions that they shouldn’t be living in.” According to Cat, corporate landlords are inherently damaging to local communities. “Their entire business is treating housing as profit instead of a basic necessity,” they said. “Everyone needs shelter. Everyone needs housing, especially if you own massive quantities of housing properties. A lot of corporate landlords have been responsible for hiking up rents, too.”

While it’s difficult to gain a sense of just how devastating the impact of Wells Fargo’s loans will be on Oakland’s minority communities (and just how many homeowners borrowed from them), renters and homeowners alike — white ones especially — have a responsibility to understand how gentrification and the displacement of Black and Brown families are inextricably tied.

I could never consciously justify preying on someone else’s misfortune by bidding on their foreclosed home in a sheriff sale auction or short sale auction. Unfortunately, plenty of developers will.

Gentrification

Sadly, unbeknownst to me at the time of signing my lease, my current living situation is apparently linked to displacement.

I recently learned from my neighbors that the studio I live in was previously owned by someone who had been evicted. For days, their belongings were hauled out onto the street.

While the corny black-and-white stock photos of the Eiffel Tower in the hallway definitely should have been an indicator that I was moving into a space marketed to gentrifiers, it was only after I moved in that it truly sunk in. After doing some extensive research, I found out that in the past seven years, my studio’s rent nearly tripled in price after getting renovated by my current landlord (according to the description, this included repainting the place and putting in new appliances). Additionally, virtually all of the neighbors I’ve met in the building are white — but every now and then, a Black family who formerly lived in the building comes back to collect their belongings kept in storage.

While the circumstances of the building’s past tenants are still unknown, it’s safe to say that my apartment was flipped in order to appeal to white tech workers. My corporate landlord, too, owns dozens of slick commercial properties throughout San Francisco. By renting from them, I realize I am complicit in the gentrification of my West Oakland neighborhood. And while my kitchen appliances and freshly painted walls are bright and new, the specter of displacement looms — ugly, eager, and omnipresent.

What can we do to combat gentrification? Here are some small, valuable ways you can get involved and support the Oakland community:

- Contribute to People’s Breakfast Oakland

- Contribute to the Town Fridge Mutual Aid Network

- Contribute to 37MLK

- Contribute to West Oakland Punks With Lunch

- Contribute to the East Oakland Collective

- Join a local tenant union