During the past six weeks, more than 4 million acres of land have burned in California due to record-breaking fires blazing up and down the West Coast. That’s an area larger than the size of Connecticut. Every morning over the past month has started with checking PurpleAir for an air quality update and pressing our faces to the window, hoping for a glint of blue sky rather than the dense plumes of gray that have grown so familiar.

Then came the day we’ll never forget — September 9 — when the smoke became so dense that it blocked the light from the sun, causing the sky to remain dark and an ominous orange long after dawn. Images of the apocalyptic San Francisco Bay Area a la Blade Runner sent shockwaves around the country, and my Instagram feed became filled with images of an orange sky and muted sun overlaid with one word: “Vote.” Against the backdrop of a president who has adamantly denied climate change and has chalked the fires up to “many leaves and broken trees,” I resonated with the urgent call for new leadership.

However, after scrolling through the image for the umpteenth time, I wondered if we were collectively simplifying the issue at hand and missing the opportunity for a deeper conversation. After all, I had voted for Governor Gavin Newsom, who ran for office in 2018 on an aggressive environmental agenda, including opposition to fracking. In 2020 alone, Newsom has issued 48 new fracking permits and 1,579 new oil and gas drilling permits. It’s imperative that we vote for leaders that both recognize the realness and urgency of the climate crisis and follow through in taking bold action. Yet this still falls short of wholly and effectively addressing California’s fire crisis, as well as the compounding crises that the fires have created for the state’s most vulnerable communities.

How do we go about this conversation in a way that gets away from political messaging and oversimplification to dig deeper?

How should we talk about California’s fire crisis?

The words we use to define a problem shape our understanding and inform how we respond and craft solutions. Therefore, I’ve grappled with the language we use to talk about the fires sweeping the state.

First, they aren’t wildfires. Not really. Describing the fires as wild renders invisible the role of humans, both in impacting larger climate conditions and sparking the fires themselves. After all, about 84% of fires on the West Coast are ignited by people. Whether that’s a pyrotechnic device at a gender reveal party gone awry, a campfire that wasn’t properly extinguished, or something more commonplace like a sparking power transmission line or a car that sends soot into dry vegetation, there are myriad ways to spark a fire, particularly when it’s hot, windy, and dry.

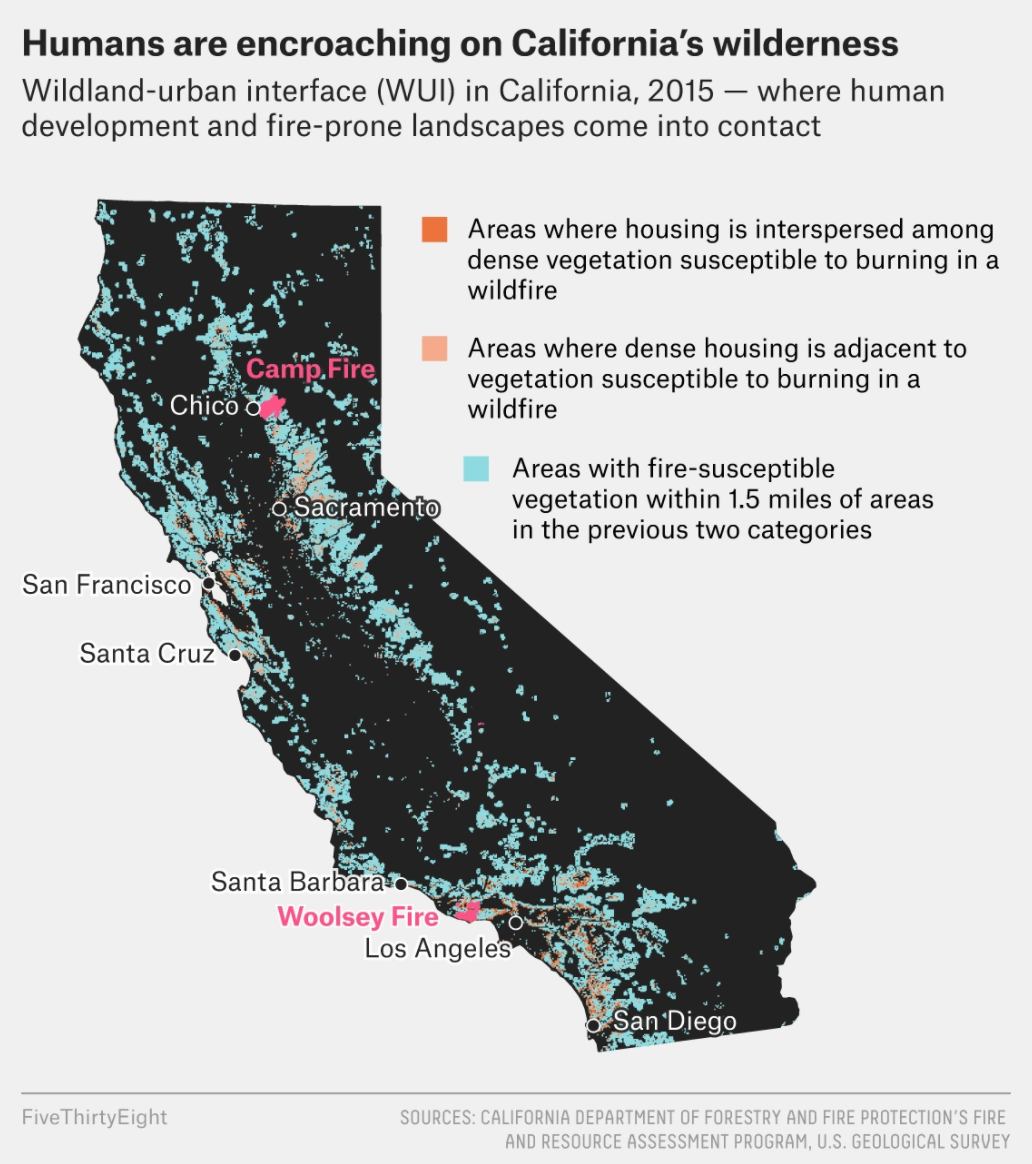

Additionally, the term “wildfire” was originally used to describe uncontrollable fires that spread through forests and brush. Today, as the line blurs between wilderness and residential areas, and as fires become fiercer in size and speed, so-called wildfires are no longer contained to wildlands. It’s becoming increasingly normal for fires to move into urban areas, decimating suburbs and towns. The Tubbs Fire of 2017, which began in a rural area of Calistoga, California, ultimately destroyed more than 5,643 structures. One year later, the Camp Fire destroyed 19,000 homes and displaced about 50,000 people from Paradise, California, and the surrounding area.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

It should be noted that the wildland-urban interface (WUI), or the area where houses and wildland vegetation meet, is the fastest-growing land-use category in the coterminous United States. In California, roughly half of the housing units constructed between 1990 and 2010 were built in the WUI, where fire risk is highest. A statewide housing crunch and sky-high rental prices in urban areas have continued to push new construction further into these zones. So, in regions where fires have historically been a natural part of an ecosystem’s cycle of growth and renewal, there are now human lives and homes in jeopardy.

For this reason, it’s not entirely accurate to refer to the recent fires as natural disasters, either. Climate reporter Kendra Pierre-Louis explains:

Most of what we call natural disasters (tornadoes, droughts, hurricanes) are indeed natural, though human contributions may increase their likelihood or intensity. But they aren’t disasters — they’re hazards. If a hurricane slams into land where no one lives, it isn’t a disaster; it’s weather. A disaster is when a natural hazard meets a human population. And often, that intersection is far from natural.

What’s more, there’s nothing natural about the size, scale, or frequency of this current fire regime, which is heavily exacerbated by the climate crisis. Much of California is currently settling into a new weather regime; stretches of drought are followed by wet winters, which spur a massive growth in vegetation, and then are followed by a return to dry conditions. Snowpack has been melting earlier, which means that the dry season stretches longer.

Then, when extreme heat wave events are coupled with dry conditions, high vapor pressure deficits are produced. Amid high vapor pressure conditions, a spark is all that’s needed for a megafire to take shape. (And, given that hundreds of California’s current fires were started by an exceedingly unique Bay Area thunderstorm that produced about 11,000 bolts of lightning, it should also be noted that lightning strikes in the continental United States are expected to increase by about 12% for every degree Celsius of rise in global average air temperature.)

It’s important to clearly illuminate the connection between the fire crisis and the climate crisis, particularly as national leadership and the broadcast media fail to do so. As 22 major fires and lightning complexes ravaged California over the September 5–8 weekend, 85% of broadcast news segments failed to make the connection between the fires and the climate crisis, according to a news analysis from Media Matters.

In an effort to make the link between megafires and the climate crisis as explicit as possible, some have called for use of the term “climate fire.” In late 2019, as fire tore through Australia, Senator Sarah Hanson-Young asked that people retire the term bushfire, imploring, “We’ve got to start calling them climate fires, that’s what they are… It is essential that there’s no ambiguity.” More recently, Sam Ricketts, the co-founder of Evergreen Action, tweeted about the West Coast fires: “These aren’t wildfires. These are #ClimateFires, driven by fossil fuel pollution.”

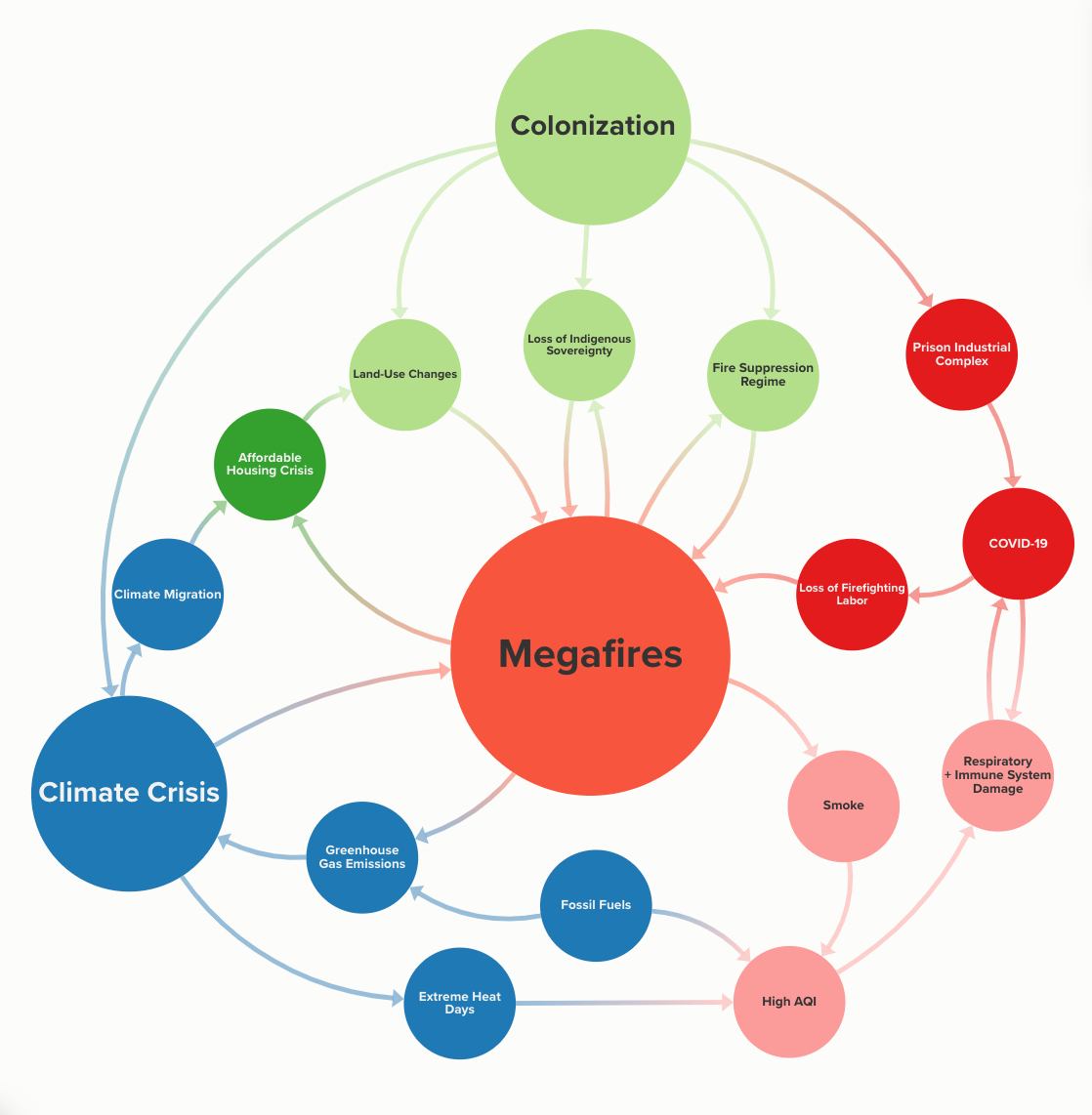

While the link between the changing climate and California’s fire crisis is undeniable, I would argue that even the term “climate fire” misses the mark in capturing the complexity of the state’s current fire regime. Drought and extreme heat days wouldn’t be so problematic if it weren’t for decades of forest mismanagement that have left California’s forests overstocked, diseased, and full of non-native species; the perfect kindling for incredibly destructive fires.

For more than 13,000 years, Indigenous peoples maintained forest health via intentional fires, an important tool in regulating ecosystems and promoting biodiversity. Ecologists speculate that between 4.4 million and 11.8 million acres were burned each year. After settlers colonized the area now known as California, Indigenous peoples were robbed of their right to be stewards of their land.

In 1850, California legislature passed a law that banned Indigenous burning, and soon after, the National Forest System was created to enforce the misguided policy of fire suppression. The NFS focused entirely on the potential damage that fires could do, while ignoring — and criminalizing — the benefits that fire could bring. As recently as the 1930s, Karuk people were shot for intentional burnings on their own land. Between 1999 and 2017, just 13,000 acres were burned annually (or about 0.2% of what’s needed to maintain forest health).

Meanwhile, in the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir in Baja, California, an area climatically similar to California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range, Indigenous peoples and nature have been allowed to continue managing vegetation. Lightning fires regularly run their course, releasing nutrients into the soil, catalyzing trees to disperse their seeds, and burning smaller trees and undergrowth while leaving more mature trees intact. Absent colonization and a strict fire suppression regime, the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir is relatively resistant and resilient to drought, high-severity fire, insects, and disease.

Therefore, there is no simple way to describe the fires currently blazing in California. These megafires are a product of complex, dynamic, and entangled processes: poor fire management practices, colonization, the climate crisis, and land-use changes.

How should we contextualize California’s fire crisis?

Similarly, there is no simple way to quantify the impact of recent megafires. We can count acres burned, structures damaged, and lives lost, but this data stops far short of painting the complete picture of devastation. Amid myriad compounding and interconnected crises, California’s fires cannot be assessed in a vacuum. Instead, they should be viewed as threat multipliers, exacerbating ongoing crises, particularly for the communities that have the fewest resources to respond. Specifically, California’s fire crisis disproportionately impacts low-income, incarcerated, housing-insecure, disabled, Indigenous, aging, immigrant, and Black and brown communities.

To name a handful of ongoing crises that are compounded by the fire crisis:

Covid-19

There are countless ways in which the megafires and the coronavirus pandemic interact to amplify each crisis. While limited definitive research exists on the implications of poor air quality on Covid-19, preliminary evidence suggests that prolonged exposure to wildfire smoke may both increase susceptibility to coronavirus infection and worsen health outcomes after infection.

Smoke irritates the throat lining, making it easier for infections to land. At the same time, fine particulates and even finer nanoparticles penetrate the lung membranes and pass into the bloodstream, damaging the respiratory system and impairing immune responses. At a time when people need their respiratory and immune systems to be as strong as ever, smoke exposure undermines critical system functions. And the same people who are most at risk for exposure to coronavirus, such as essential workers, who are disproportionately Black and Latinx, are also the least likely to be able to stay indoors when the air quality is dangerous.

Meanwhile, for the hundreds of thousands of people who have been forced to evacuate their homes due to encroaching fires, deciding where to find refuge becomes an increasingly loaded challenge. Some evacuees have been able to stay with friends and family nearby or in hotels that have been converted into makeshift “non-congregate” evacuation shelters. Others land at emergency shelters, where thousands of people sleep on cots separated by clear shower curtains. Still others make the decision to sleep in their cars, a trade-off which heightens their risk of smoke exposure but limits potential exposure to Covid-19.

“We have to have it in our minds that grouping people together and shoving them off in a hurry to one location might present an equal, if not greater, life-threatening risk,” says Vance Taylor, part of the executive team at the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, explaining why typical evacuation shelters aren’t a safe option, particularly for elderly evacuees and folks with preexisting conditions that heighten their risk for severe illness from Covid-19. Medically vulnerable populations must navigate multiple, potentially life-or-death scenarios at once.

Extreme heat

As three of the largest fires in the state’s history burned in Northern California, Labor Day Weekend brought record-high temperatures across the Bay Area. In San Francisco, temperatures rose to the triple digits, shattering same-day records. Residents of San Francisco, a largely air conditioning-free city (only ~10% of homes have central AC), had to choose between baking in stifling hot apartments or opening up windows and venturing outside, exposing themselves to air with an AQI between 200–350 (which is considered a serious to extreme health risk for the general population).

In heat waves past, residents might avoid heatstroke by flocking to air conditioned libraries, museums, and malls. However, amid a pandemic, public indoor gathering spaces remained closed. Cooling centers were an option for some, but they operated at reduced capacity to promote social distancing. Extreme heat, poor air quality, and Covid-19 all pose serious immediate health risks for pregnant people, folks over the age of 65, and the chronically ill, leaving scarce safe options.

Beyond San Francisco, millions of Californians have dealt with extreme heat by cranking their fans and air conditioning units. As electricity demand has surged beyond supply, electricity providers have instituted rolling power blackouts to reduce stress on the larger grid. For many, temporary blackouts are a nuisance but a relatively minor inconvenience. For folks with disabilities, who may rely on electricity to keep medical equipment and devices functioning and to keep medicine refrigerated, interruptions in electricity service can be life-threatening.

Housing insecurity

Meanwhile, there are many individuals who don’t have the option to escape the heat or the wildfire smoke. Tens of thousands of Californians are currently unhoused or housing-insecure, and staying indoors isn’t a possibility. People experiencing houselessness are also disproportionately impacted by chronic health issues, which are exacerbated by prolonged exposure to poor air quality. Making matters worse, there are fewer indoor escapes since the pandemic began; public restrooms and spaces have closed and resources at shelters have dwindled.

Exploitation of essential workers

Tens of thousands of farmworkers, many of whom have been working without hazard pay throughout the entire pandemic, and who have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, have again had to make the choice between working in high-risk conditions or sacrificing their pay. Most farm workers don’t have access to paid sick days or vacation days, and working inside isn’t an option. Emma de La Rosa, a policy advocate with Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, says, “Farm workers don’t have the option of staying home, of being indoors. We often recommend that people stay indoors when the air quality is extremely harmful. Farm workers don’t have that luxury. It’s either I breathe in smoke — or I don’t work.”

De La Rosa elaborates that farm workers are working for minimal pay in unsafe conditions; they’re not being provided with appropriate information about the air quality, information on how to wear masks correctly, or protective gear itself. According to a recent survey by United Farm Workers, 84% of farm workers have not been given N95 masks or the equivalent, despite the fact that employers are mandated by law to distribute protective gear and provide hourly air quality updates when the AQI is above 150. While employers are legally obligated to keep their workers safe, Cal/OSHA is failing to enforce labor protections. For farm workers, and particularly undocumented folks and folks that don’t speak English, it can be challenging, risky, and even impossible to report labor abuses and access social services. Some have spoken up and then were not called back for the next harvest. Others fear the real threat of deportation and separation from their families.

Prison industrial complex

California’s incarcerated population, 78% of whom identify as nonwhite, has been on the frontlines of the state’s fire crisis while bearing disproportionate impacts of several of the overlapping crises above, including Covid-19 and labor exploitation. Since the early 1900s, California has relied heavily on the labor of incarcerated folks to fight fires.

While Cal Fire compensates its firefighters with more than $148,000 a year, incarcerated firefighters earn as little as 8 cents an hour for their labor. The work is grueling and dangerous. It’s not uncommon to work a 48-hour shift. Despite the fact that incarcerated firefighters oftentimes work alongside full-time firefighters, it has historically been nearly impossible for these trained crew members to land jobs in the field upon release. People with criminal records were barred from becoming emergency medical technicians, which is a required certification for becoming a professional firefighter.

(Three weeks ago, Governor Newsom signed a bill to make it easier for formerly incarcerated folks to get jobs as professional firefighters upon their release.)

This year, California’s ranks of incarcerated firefighters shrunk about 30%, in large part due to early releases following coronavirus outbreaks in prisons across the state. Twenty-eight of California’s 35 state prisons have confirmed cases of coronavirus, totaling 14,208 reported cases across the state. Several facilities suffered significant outbreaks and fatalities due to inadequate personal protective equipment, cleaning supplies, testing, and ability to socially distance. While irresponsible transfers between facilities and mismanagement are partially to blame for the outbreaks, it’s also nearly impossible to keep incarcerated communities safe and healthy amid a pandemic in the overcrowded, poorly ventilated, and under-resourced state prisons that characterize the contemporary prison industrial complex.

No simple fixes

There are no simple fixes to California’s fire crisis, because it isn’t a simple problem. If we continue to view the fire crisis through a singular lens, we will not be able to mitigate the threat of future megafires. Similarly, if we fail to recognize the breadth of their direct and indirect impacts, our solutions will be narrow and incomplete. PG&E can renovate the entirety of its electric infrastructure, and California will still be a tinderbox of dry vegetation, set ablaze by other sparks. Insurance companies can drop coverage and cities can ban new developments in WUI zones, and people will still need a place to live. And on and on.

It has never been more evident that the fight for justice and the fight against environmental collapse are one and the same. We must call for bold climate action while we lift up the Land Back movement and demand that ecosystems be returned to Indigenous stewardship. We must advocate for disability justice, transformative justice, worker justice, immigrant justice. If our intention is to mitigate risk and minimize harm, particularly for those who are most vulnerable to impacts of the new fire regime, this moment calls for expansive, holistic solutions, and action from the masses.