Not many people can say they’ve come within a whisker of $100 million, but that’s my claim to fame right now. Five years ago, I was known as the goofball who thought there was money to be made by disrupting the kitty litter industry. Now I’m known as the goofball who lost a fortune when someone else turned that much-derided idea into a lucrative business.

Sign up for The Bold Italic newsletter to get the best of the Bay Area in your inbox every week.

It was just another forgettable shelter-in-place Wednesday when an ex-girlfriend called me out of the blue to tell me that I had to turn the TV to RuPaul’s Drag Race immediately. I flipped through the channels until I found a drag queen auditioning for the title of Kitty Girl 2020. It was a mini-challenge sponsored by PrettyLitter, the company I’d co-founded. The company I’d let slip through my fingers.

As the queens scrambled into cat drag, racing to out-feline one another around a giant PrettyLitter-branded cat box, I plopped down on the couch to watch. I was torn by competing emotions: vindicated because this display was clear proof that the naysayers had been wrong about the kitty litter idea, but also gutted for having lost out on such a monumental opportunity. The long nights of product iterations, the sweaty practice pitches in front of the cameras, the high-stakes reality TV, the betrayal, the absurd heartache — it had all been for nothing. Well, maybe not nothing. I did get some fodder for a blog post. Let me back up and tell you the full story.

California dreamin’

Like so many other people in Silicon Valley, I’m not a Bay Area native. I came to California by way of Toronto. Back home, I’d attended a hacker bootcamp talk entitled “Top Things I Hate about Silicon Valley Culture.” The speaker, a jaded Canadian technologist, ranted about a crazy billionaire who’d bought a chunk of downtown San Mateo because he thought he could train young people to be superior entrepreneurs. The billionaire hosted a superhero-themed startup incubator and invited his big-wig tech buddies like Elon Musk to teach classes.

“He’s a phony!” the speaker grumbled. “He’s spreading idiotic ideas about company building! And, anyway, doesn’t a venture capitalist have better things to do?”

Sitting in the audience, I thought, Actually, that sounds kind of amazing!

Later that night, I went home and researched the billionaire’s school. Draper University of Heroes was unconventional, to say the least. Its founder, Tim Draper, was Theranos’ first investor — and its last staunch defender. He famously spends his free time trying to split California into three states. He also compels startup trainees to kill chickens, sings while keynoting business conferences, and jumps into swimming pools fully clothed. And yet Draper U still seemed like a much better way to learn about startups than anything else I’d ever heard about.

At the time, I was trying to transition from a career in PR sales to early stage tech companies, and I was willing to try just about anything to get there. I decided to put my sales skills to work. I tracked down Tim Draper’s email, pitched him on my entrepreneurial experience, negotiated the price of tuition, and enrolled in the program at cost.

A few months later, I graduated from Draper U, a tad older and a tad wiser. I had a couple of pivotal experiences, a new network of professional contacts, and one failed startup idea under my belt. I was more eager than ever to dive into the world of entrepreneurship. It was right around then that I met the cat lady who changed my life.

Cat litter Carly

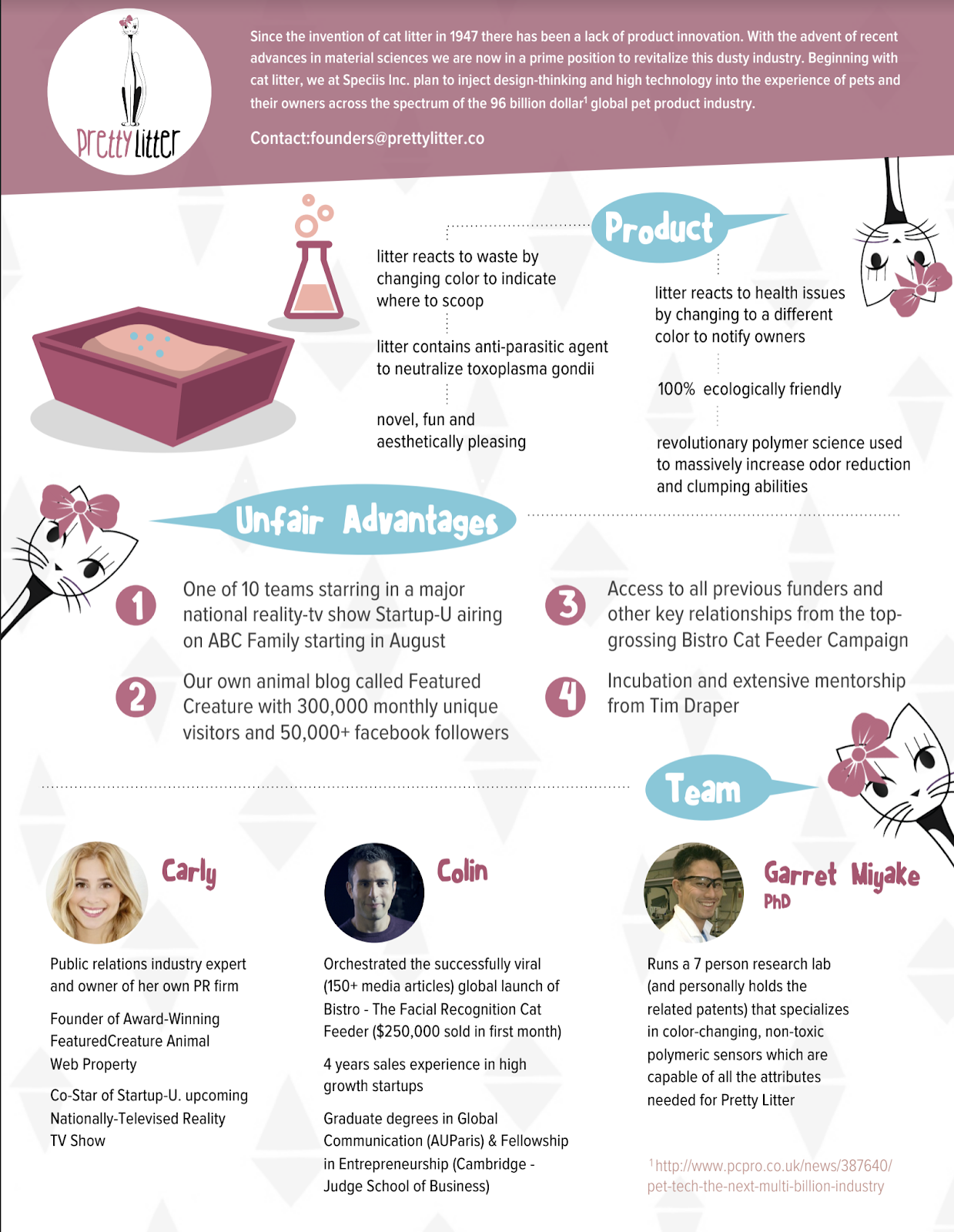

Carly Martinetti was a charming animal lover from L.A., and, like me, she had a background in PR. She had recently been cast in Startup U, a short-lived reality TV show on ABC in 2015. Carly was cast by the production company along with nine other actors and models that made up the 10 “stars of the show.” They also included students picked by Draper U like me, but we were in the background with no speaking roles. The 10 cast members, once selected by the production company, then also applied to Draper University and had to be accepted.

The show was a $250,000-per-episode money pit that cost ABC a pretty penny, but it was a good opportunity to spotlight some inventive ideas and to promote the Draper U brand.

Carly reached out to me to ask my advice about her idea: color-changing kitty litter. She proposed making the unpleasant chore of changing the litter box less dusty and smelly. I immediately latched onto the wacky idea. It seemed more investable than other Draper U ideas, it had a catchy name, it seemed made for TV, and it was bolstered by the 300,000 people who visited Carly’s popular animal blog every month.

I hate to brag, but I happen to be something of a pet-tech expert. That was the reason Carly had approached me. I’d previously worked on a project with a good friend named Mu-Chi, who’d spent years running a Taiwanese A.I. lab. We worked on the world’s first facial-recognition cat feeder, Bistro, a product that could recognize your cat, monitor its health, and tell you if it was eating properly. I’d also launched a side project called Petsy, the world’s first loyalty card for pet owners, and it had made a splash in the press.

Carly asked me to join her on the reality show as her co-founder. I had a decent-paying sales job at a PR startup, but this seemed like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I could play a substantial role in a TV production and launch a fascinating — though admittedly unusual — product. But was it worth the risk of looking like a fool if it flopped?

I had no idea if PrettyLitter would take off, but I knew that if I didn’t try, I’d always wonder, What if? I decided to pounce on the opportunity like a kitten on a feather teaser wand. I quit my job, packed my bags, and bought a one-way ticket to San Francisco. I’ll bet that in the history of the world, I’m the only person who ever came to the city in search of riches in the litter box.

Purr-fect proposition

During the time I was on the show, I worked day and night. I took power naps — cat naps? — rather than sleeping because I was afraid of missing out on some opportunity. I reached out to contacts in my network and called in favors from people I’d known for years. I pulled every trick in the book to give PrettyLitter a leg up on the competition and to increase our chances of winning Startup U.

Carly’s idea was definitely interesting, but I had a hunch about a way to make it more marketable: making the litter medically diagnostic. If we modified the composition of the litter, it could track the health of cats by changing color based on different chemicals in their urine. The litter could help cat owners determine whether their kitties might need to visit the vet. With help from a friend at MIT, I found a chemist whose research specialty was color-changing polymers. He agreed to become PrettyLitter’s official scientist. It was a small step for us, but a giant leap for kitty-kind.

I was also familiar with a phenomenal branding company called Sketch Deck. They were way outside of our price range, but I decided to try to make a deal with them. In exchange for creating free marketing materials for PrettyLitter, Carly and I promised them outsized exposure, an on-camera talk to the other Startup U teams, and free broadcasting on ABC’s networks. Fortunately for us, they agreed to our terms. We now had a marketing team behind us. We seemed to be going places.

Armed with some stellar marketing materials, I brought onboard an intern who had studied at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Daniel was diligent and enthusiastic, and we were both convinced that he had a bright future.

I felt like we were really chugging along, which, ironically, worried me a little. I didn’t want to fall prey to a business shark like Tim Draper, so I suggested that we draft some legal documents. I dug into my own pocket to hire an attorney who could help us navigate the dangerous waters we were wading into.

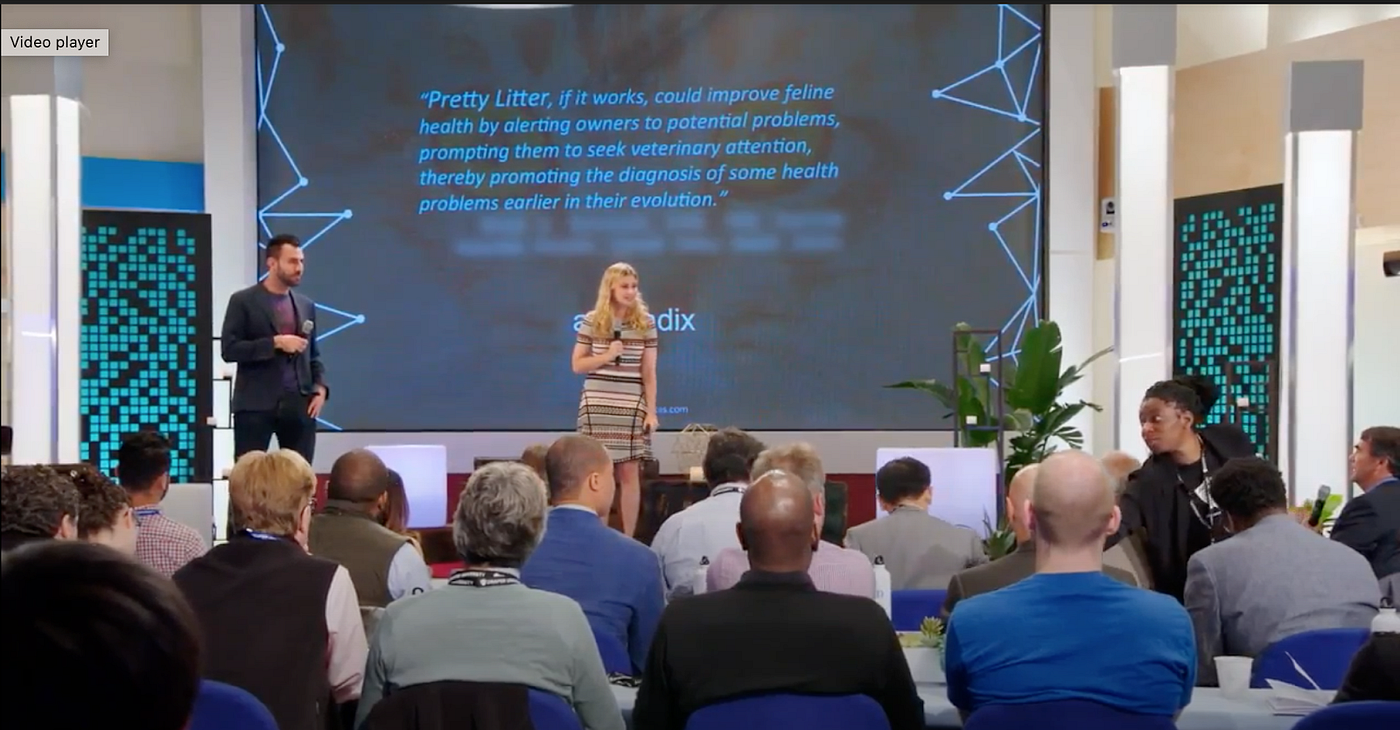

Tensions were high as we raced to prepare for Demo Day when we would present on stage in front of the Startup U judges. After all the teams made their pitches, the judges would select their winners and offer term sheets. Before the competition, the Draper U admin gave us a list of the judges, all of whom were investors, and they asked us to research them in preparation for our presentations.

The night before our pitch, I sleuthed the investors’ emails and sent them our professionally designed materials in advance. We got positive feedback, but when the judges asked about the other teams’ pitches, word got back to the school about my extracurricular emailing. The other teams howled in protest. “That’s unfair!” they cried. The program admin gave me a stern talking to, but the social hack worked. We were the only team that got prearranged meetings. We also got the investors’ attention. At the time, it seemed like a reasonable business gamble that had paid off.

After a long, sleepless night, Demo Day had arrived. All the nervousness that had been building for weeks culminated in an intense few minutes on stage in front of dozens of investors and hundreds of thousands of television viewers. Carly and I pitched PrettyLitter together. She was a little annoyed with all my unconventional tactics, and, to be honest, I don’t blame her. But there was nothing we could do now but cross our fingers and hope for the best.

Houston, we have a paw-blem

Fundamental differences in personality doomed my relationship with my co-founder. Carly was undeniably the outgoing star of the show, the face of the company, while I did a lot of the behind-the-scenes work. I’m the first to admit that some of my tactics were… off the beaten path. But that’s not to say that they didn’t work. They did make Carly uncomfortable, especially after the admin called her into a meeting to discuss, among other things, my pre-competition emails to the judges. They told her that what I’d done was “against the rules.” Carly decided that from then on, I couldn’t do anything without checking with her first. That didn’t bode well for our relationship.

Tensions between us escalated in the weeks that followed. Then, not long after pitching on Demo Day, after I’d put in a lot of 16-hour days, she gave me the hook.

The joys of being fired on national TV

“You know, Colin,” Carly told me on camera. “I just don’t think we’re meant to work together on this… it’s my thing and I don’t want to do it with you, that’s really what it comes down to.”

And just like that, I was yanked off the stage and out of the program, before I’d even heard the official results of the pitch competition. I later found out that PrettyLitter placed in the top three and won a $50,000 investment offer from Tim Draper. Part of me was truly happy for her, but a less generous part of me was jealous of her success.

Early investors struck gold because, over the next few years, PrettyLitter became a thousand times more successful than the other startups on that stage. It was the only company on Startup U that actually realized hockey-stick growth. PrettyLitter eventually achieved the rarest of feats: product-market fit.

But wait, there’s more!

You’ve gotta be kitten me!

A few weeks after the show ended, I got a call from Daniel, the intern we’d brought aboard to help with the workload. After we exchanged pleasantries, he casually asked me whether I planned to work on my own cat litter product. I told him that without Carly, I didn’t see a way forward. I also admitted that some of the wind had been taken out of my sails after she unceremoniously booted me from her company.

“Oh, good,” he said, his voice cheery. “Just so you know, I’m the new CEO of the company. Talk later!”

He hung up before I could react, and that was the last I ever spoke with him.

It’s worth noting here that Daniel was uber-professional from the start. He’s charismatic and clever, and he struck all the right chords in conversations. Prior to taking on PrettyLitter, he’d worked for the congressional chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. I’d hired him from a large pool of applicants because I saw tremendous talent in him — talent that helped him rise from unpaid intern to CEO in a matter of months. Machiavelli couldn’t have done it better.

To be fair, Daniel would have been successful in whatever passion he pursued. But he certainly took our kitty litter idea and ran with it all the way to the bank. His masterstroke was licensing. Carly and I dreamed up the product; Daniel found a comparable product launched in 2012 overseas under a defunct label, licensed it, and slapped branding on it to make it commercially successful. He truly has the heart of a CEO.

After Daniel took Carly’s job, she ended up at the niche startup PR firm that I’d left to work with her on PrettyLitter. I’d told her about my former employer, and she reached out to them about a job shortly after the show wrapped. Life has a funny way of coming full circle sometimes.

I’m no sourpuss

Back in the early days of PrettyLitter, a blunt PhD friend said to me, “Your team has zero expertise, IP, or competitive advantages in manufacturing, chemistry, consumer products, animal health, diagnostics, or distribution. And cat litter isn’t an industry that needs disruption.”

The vast majority of my smart, business-savvy friends told me the same thing, after they were finished laughing at me, that is. It’s next to impossible to explain to people working in artificial intelligence, enterprise solutions, or cryptocurrency why I’d quit my job to work on color-changing cat litter. They thought I was settling.

But the real kicker is that I was right. I saw a highly unorthodox opportunity to solve a dusty, decades-old problem that everyone else ignored. Granted, my decision to help build a better kitty litter was fueled by the glimmer of Tim Draper’s magic-investor pixie dust, the absurdity of 21st-century reality TV, and the false promise of a conniving cast of characters fit for a Hollywood movie. But in the end, my massive gamble was justified. There was gold in them hills (of kitty poop). I just couldn’t cash in.

According to a 2019 Forbes article, “More than 2 million bags of PrettyLitter have been purchased since 2016 at $22 a bag, and it’s the fastest-growing feline-focused company in the U.S.” In the article, Daniel cheekily added that by the end of 2019, “PrettyLitter will have grown 4,500% in four years. And we’ve done it profitably the entire time.”

The “we” part gets me.

I can estimate, conservatively, that the valuation of PrettyLitter is more than $100 million based on the $44 million in stated revenue as of May 2019 and the CEO’s quote of growth of 4,500%.

Having lost out on being part of such a massive fortune, I feel like I’m entitled to drop the occasional nugget of wisdom into the palm of those who stick with me to the end of my story. Hard-learned lessons are character builders, after all. So here’s my sage advice to my readers:

Believe in your bat-shit crazy ideas. Start where no one else is looking, and do what no one else is doing. Put in the time, trust the process, and when the rules don’t suit you, break them. If you can do all that, and if you’re blessed with a healthy dose of good luck, you might find yourself building a global kitty litter empire.

Failing that, you’ll have one hell of a story.