“THEY DON’T WRITE GOOD.” Cathy Edens, a San Jose copyeditor, is hand-stitching these words — Donald Trump’s — with tangerine-colored thread on a lacy white cotton hankie. As she embroiders the president’s 2016 dismissal of the New York Times, she captures his bad grammar with each prick of her needle, turning adornment into a tool for empowerment. “This is proof that I have enough determination to stab something a thousand times,” she reflects.

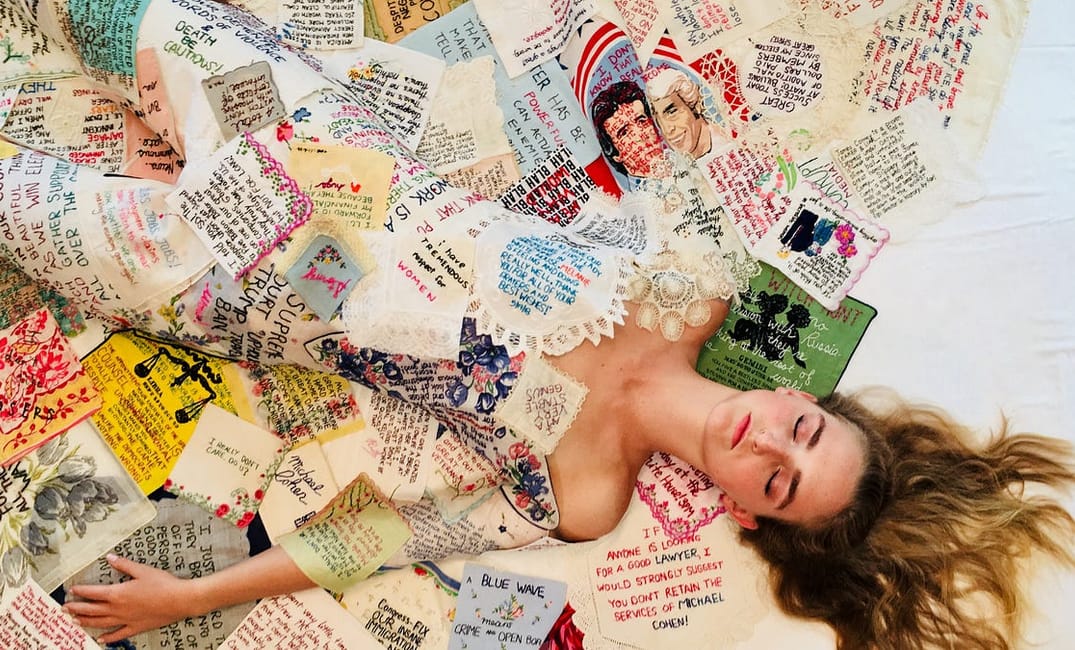

Edens is part of a growing posse of crafty activists who are discovering that the sewing needle may be mightier than the pen when it comes to fighting President Trump. They are recording his tweets and spoken words on doilies, dish towels, and scraps, then adding their handiwork to a global, crowdsourced embroidery collection that is gaining participants as it travels to galleries, store windows, conferences, and museums around the country.

“What you are doing feels difficult, challenging, almost repelling — it’s the personal intimacy with the words.”

“We are recording history,” says Leslie Dumont of San Francisco, who has already contributed six embroidered pieces to the Tiny Pricks Project — a material record of Trump’s presidency that includes more than 2,400 embroidered entries so far. Dumont thoughtfully pairs her chosen quotes with chic vintage handkerchiefs—such as the word “PUSSY” emblazoned multiple times around a stylized black cat. “The project will be in a museum some day,” she says.

Seeing hateful words in sweet settings can be shocking and, sometimes, funny. Picture delicate lace framing the declaration “I COULD STAND IN THE MIDDLE OF 5TH AVENUE AND SHOOT SOMEBODY.” Or vintage roses encircling the boast “I HAVE THE BEST WORDS,” lovingly stitched, with imperfections revealing the human hands behind the effort. But the unlikely juxtaposition of homespun and Trump-spoke also turns these tiny pricks into a powerful, lasting indictment.

“I am collecting a material record of this presidency and documenting the protest against it,” says Diana Weymar, the artist behind the Tiny Pricks Project. Weymar receives submissions daily, then posts them on Instagram. “The things that he is saying are being remembered because they are so striking.”

Weymar didn’t envision a global movement when she first put needle to fabric in frustration on January 8, 2018. Grabbing a traditional golden-hued cross-stitch cushion cover that featured a spray of pink-and-purple roses, she boldly sewed the words “I’M A VERY STABLE GENIUS” in bright yellow across the center, like jarring graffiti. Then she posted a photo of it on Instagram and began a meditative practice in the vein of Windy Chien’s knot-tying, fueled by an activist’s drive for political change. Although Weymar had led three public-art projects before, that wasn’t the initial intention for the Tiny Pricks Project, partly because of its emotional toll.

“I was hesitant to inflict this subject matter on others. A lot of people are participating against their will; they are repulsed by the things Donald Trump is saying,” says Weymar, who now stitches a piece daily. “What you are doing feels difficult, challenging, almost repelling — it’s the personal intimacy with the words.”

Indeed, participants are discovering that using Trump’s own words as a weapon against his ideas is painful but cathartic too. “You are sitting with these words, and they are awful words,” says Angie Herrera, a Latina artist in San Jose. “It’s so cringy.”

Angry and despondent, Herrera felt powerless as Trump debased the migrant caravan south of the U.S. border. Then she learned about the Tiny Pricks Project and was moved to hold the president accountable for his words by recording some of his anti-immigrant vitriol on a niece’s outgrown campesina, a traditional Mexican floral dress.

“I was crying as I did it,” Herrera says as she remembers the evening when she created Tiny Prick number 420. “I surrounded myself with comforting things — a mug of white wine, chocolate chip cookies, and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. At the end, I felt so light.”

The satisfaction that comes from taking concrete action against a force that seems impossibly strong is one reason why the Tiny Pricks Project has ballooned from the work of a lone creator with fewer than 1,000 Instagram followers to a global phenomenon with hundreds of contributors and more than 43,000 followers. The project’s first exhibition was held in April in San Francisco at the Mule Gallery in North Beach. Soon after, a summer show in New York City at Lingua Franca catapulted the project to fame.

Weymar has even launched Tiny Pricks Project UK, a spin-off focused on Brexit and Boris Johnson, and she’s plotting a 2020 U.S. exhibition tour strategically with the presidential election in mind. “New York and San Francisco are cities inclined to be supportive of the project and offer activism opportunities,” Weymar says. “I am considering other cities, perhaps in red states, where there might not be the same kind of ‘easy activism.’”

At a time when many feel angry and helpless, Weymar has become a muse. And Herrera is among the inspired, having submitted several Tiny Pricks pieces and identifying herself as an “artivist,” part of a growing corps of creatives pairing traditional crafts with bold statements in unexpected contexts. Perhaps the most visible example of artivism came in 2017, when hand-knit pussyhats topped thousands of demonstrators at women’s marches around the world; it began when two women leveraged social media and the global knitting community to protest Trump’s vulgar language by encouraging people to make — and wear — the pink hats. Herrera finds more inspiration in The Subversive Stitch by Rozsika Parker and on Instagram accounts such as #subversivecrossstitch and badasscrossstitch.

But there is something special about this particular collective effort — its immediacy, enormity, and documentary nature, all captured in a form that has long been associated with women and women’s labor.

Herrera recently led a free workshop at Britex Fabrics in San Francisco for like-minded Bay Area residents who are eager to contribute to Tiny Pricks. That small pocket of resistance — dressed the part in T-shirts printed with “Nasty woman” and “Nevertheless, SHE PERSISTED” — met recently at the decades-old business, now located on Post Street. Some were experienced stitchers who arrived with a rainbow assortment of thread, while others came empty-handed, new to embroidery and keen to learn.

Seventeen-year-old Mooka Dhormpa had no idea what she was getting into. Her mother had registered her and sister, Jackie Dhormpa, for the event, thinking it was just a free needlepoint class. “She’s trying to feminize us,” says Jackie. “Last weekend it was chocolate-making.” The siblings parachuted into the ultimate stitch-and-bitch session and landed gracefully, pleased to discover that there was more than just embellishment on the agenda.

“I think it’s really cool that we’re doing something feminine against this anti-feminist man we hate so much,” says Mooka Dhormpa, from Oakland.

This is hardly the first time art is being employed for political aim. The long-running marriage includes anti-government protest songs, posters, guerilla theater, and street art. But there is something special about this particular collective effort — its immediacy, enormity, and documentary nature, all captured in a form that has long been associated with women and women’s labor. “It goes from social media tweet to embroidery and back to social media,” notes Weymar. “We witness someone’s creative process.”

Tiny Pricks owes a debt to monumental projects of the American past, including the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the AIDS Memorial Quilt, even as it draws its daily lifeblood from such rapid and ephemeral sources as Twitter and Instagram. Both foundational memorials gain strength from multitudes — the repetition of names upon names, each representing a singular person lost, far too many to bear. “It’s too much to fathom,” says Weymar. “You constantly switch back and forth from ‘This is an individual’ to ‘This is an epidemic.’”

Likewise, the whole of Trump’s lexicon is staggering. When Weymar mounts exhibitions (which include only portions of the collection), viewers are reminded of how accustomed we have become to the breadth and scope of his words — to the American president lambasting, denigrating, and mocking. With so much material, there is a risk that we’ll become desensitized or give Trump a pass. But by capturing his comments in individual embroidered pieces, the pricksters may be ensuring that each outrageous comment still has weight and a place in history.

Multitudes indeed. With more additions being tweeted—and stitched—daily.