For most, social distancing has meant isolation. With interactions limited to partners or immediate family, loneliness is settling in single-family homes throughout the country.

Elsewhere, dance parties, campfires, and group yoga sessions abound. In the Bay Area, people living in cooperatives (co-ops) are sheltering in place in households ranging in size from five to 41 people. “We’re probably the least lonely people right now,” says Stephanie Pakrul, who lives in a 41-bedroom warehouse turned “startup community” in San Francisco called 20Mission.

Given that household transmission is a driver of infection for Covid-19, residents in communal homes are especially vulnerable. Co-ops consider themselves whole quarantine units, taking precautions against infection outside the home but treating their housemates as family. That affords moments of connection at a time when it is badly needed.

“It’s better to be able to hug someone in the world,” says Jeremy Blanchard, resident of a seven-person co-op in Oakland called the Hearth.

Larger homes like 20Mission are taking steps to limit group interactions, but complete isolation is impractical in a building with one kitchen and two bathrooms, says Andrew Ward, a seven-year resident at 20Mission.

“We’re not jumping into cuddle puddles or anything like that,” he says. The house’s famous Tasty Tuesdays (read: pizza competitions and hot-pot extravaganzas) have been postponed indefinitely, and the last house meeting was held over Zoom. Still, Call of Duty tournaments in the game room seem to be growing in popularity, and Ward describes common spaces in use “as normal.”

Threats of Covid-19 aside, almost all of the co-ops had the same message: Community is blossoming.

When one resident at 20Mission started experiencing fever, cough, and difficulty breathing, it seemed like an outbreak waiting to happen. The previous autumn, someone in the community caught a nasty stomach bug, and a number of people fell sick soon after.

After a virtual consultation, a doctor recommended that the resident self-isolate in her room; due to limited testing capacity, the doctor did not recommend testing. Friends from within the community have been cooking her food, delivering it room service–style to her door, and taking dirty dishes away — all while wearing gloves. The house donated one of the two bathrooms to the person while she self-quarantines, causing a few grumbles on the house Slack. So far, no one else has experienced Covid-like symptoms.

Other co-ops have systematized the fight against Covid-19. Only a few people at the massive Casa Zimbabwe, part of the Berkeley Student Cooperative, are allowed to touch the serving spoons. And then there’s the system for bringing in groceries at Chrysalis co-op in Berkeley: an assembly line of people washing “outside” containers and transferring food to “inside” containers.

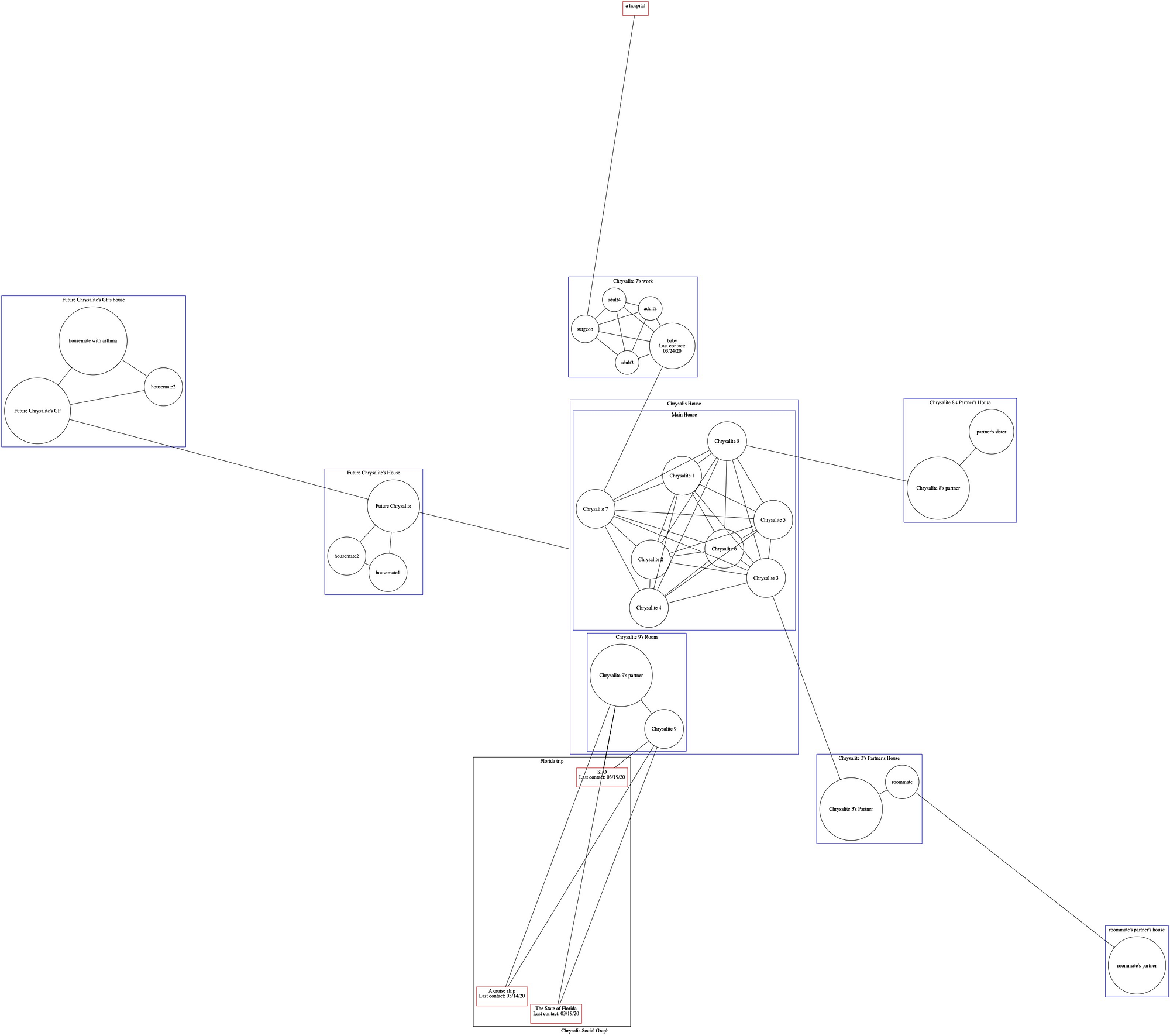

Chrysalis also mapped a visualization of the group’s “Covid-bonded network” — a complex web of the contacts of each house member and the contacts of those contacts. In fitting with the DIY spirit often associated with co-ops, members at Toadhall in Berkeley have filled buckets and spray bottles with their own mixtures of vodka and water — always in keeping with the 65% alcohol standard, of course. At another, copper foil covers all the doorknobs.

Threats of Covid-19 aside, almost all of the co-ops had the same message: Community is blossoming. Once poorly attended communal dinners now have 100% attendance — every single night. At Chrysalis, a Monday night dinner turned into an impromptu formal party, replete with a photo shoot, three-course meal, and dancing, accompanied by live piano and guitar. Not to mention sweating together in the homemade mobile sauna in the backyard. (Yes, it has been to Burning Man.) Other co-ops report open-mic nights, birthday parties, herbal medicine teach-ins, and board game nights — with games homemade by a resident board game designer.

“We’ve done a lot of thinking and discussing about collapse and about disaster preparedness — what does it look like to really build and sustain a resilient community? We’re getting to practice what we’ve always talked about.”

“The strongest thing about this time has been a sense of togetherness. To actually be together here every day is remarkable,” says Morgan Curtis, who lives in a yurt at Canticle Farms, a nonprofit in East Oakland that’s home to 20 people, multiple buildings, and a central garden. On a video tour of the farm, Curtis points out an avocado tree, a beehive, a baby plant nursery, and beds of squash, kale, and collards. Outside, a sign offers neighbors herbal medicines like plantain leaf and verbena. “The invitation to shelter into this place has almost felt needed for some time.”

It is not by coincidence that co-ops seem quite prepared for shelter in place. Canticle Farms, for one, has been preparing for major societal disruption. Its mission is to be a model for a sustainable society amid a collapsing world. “We’ve done a lot of thinking and discussing about collapse and about disaster preparedness — what does it look like to really build and sustain a resilient community? We’re getting to practice what we’ve always talked about,” Curtis says. Canticle Farms also has a space dedicated to restorative practices for resolving conflict.

Curtis warns that this won’t be the last time we see a massive disruption in our lifetime, nodding to potential disasters associated with climate change. She urges people to reckon with the lives they have built for themselves. “What does it take to build lives for people where they want to shelter into that life? How do we have a more resilient urban fabric for people to be nurtured?” Curtis says.

Co-ops are designed to manage conflict, with their chore wheels, house rules, and accountability structures. It may be more challenging to make decisions in homes where such structures are not in place, says Lydia Laurenson, a member of Kaleidoscope, an eight-person co-op in San Francisco that she characterizes as “tech hippie.” At Kaleidoscope, decisions are made by consensus. A series of house meetings resulted in community guidelines, a 13-page document that has been shared and revised by co-ops everywhere. Also, when new costs were added, housemates adjusted rent portions based on who can pay what, given the circumstances.

Not everything has been singing kumbaya around a campfire, though. Many Slack arguments later, Pakrul reports that she has “literally never seen this much conflict in seven years,” qualifying that it’s “not that bad.”

There have been sticking points, and many co-ops are emptier for them. Those with compromised immune systems have left, as have those who assess risk differently. 20Mission estimates that only about 75% of its rooms are occupied at the moment, and a resident with an autoimmune deficiency at Rose House in Berkeley has left. At Casa Zimbabwe, numbers are down from 120 to about 50.

When one person’s actions are inextricably intertwined with all of their housemates, decisions get hard quickly. Conversations about intimate partners are among the most challenging. Some have chosen to move out rather than be separated from their partners. Other co-ops are playing host to new housemates as romantic partners move in indefinitely. The Hearth temporarily instituted a “no partners allowed” policy, so Blanchard is sheltering in place without his partner.

“In any other case, I could do whatever I wanted outside the house. But I can’t. Now I have to take six other people into account in a big way,” says Blanchard, who describes this as the hardest decision he has had to make while living communally.

When tensions arise, the idyllic quickly turns sour.

“It’s like a cage,” lamented a resident at one Berkeley co-op after disagreement plagued the house. (They requested to remain anonymous.) “We tried to discuss and instate cleanliness practices, but not everyone follows them. It’s like herding cats,” they said, accusing a housemate of “self-exceptionalism” because he refuses to compromise on going to work and riding public transit. “This person is not considering the well-being of these housemates,” the resident said, since he refuses to have a conversation about his practices. The resident is now looking for new housing.

“People say hell is other people,” says one resident of a San Francisco co-op, referencing a Jean-Paul Sartre play in which three people are trapped in hell — a single room. The advent of Covid-19 has brought the highest highs and the lowest lows, he says. “No one says heaven is other people, too. But I do, and that’s why I live in a co-op.”