The first time I noticed Benji Wong was around a year into writing my arts and entertainment column at AsianWeek newsmagazine, which operated in San Francisco until it closed in 2009. I was hungry that first year, a newly minted professional journalist fresh out of college, and took any story lead offered, writing nonstop, hungry to earn my byline. I was literally starving, too, as my days and nights filled with cultural events, festivals, and award shows. I often skipped meals, nibbling instead on odd bits and pieces of quiches and crudités at press conference hospitality tables. This is where I first saw Benji, hovering somewhere between the shrimp puffs and sausage-stuffed mushrooms, wearing the black leather fedora that I would come to know so well.

This happened at least once a week near some catering table somewhere in the city. We never spoke to each other or said hello but found ourselves in an odd ritual: We’d somehow find ourselves opposite each other across the table or in line next to each other, quietly filling our cocktail plates. Before retreating to our respective corners of the room, he’d lift his appetizer in a mock toast, and I would do the same. Other times, I saw his fedora from across the room as he leaned in closely, arms crossed, to someone whispering into his ear. His shoulders would bounce as he chuckled and shook his head. Sometimes, I recognized the people whispering — Chinatown business owners, film publicists, technology startup founders and CEOs, local politicians, and one future mayor.

Who was this old guy who seemed to know everyone? I mean, what was his deal, anyway?

As my column grew for the publication, I shrank: My skin grew loose and sallow; my bones protruded from my spine. My feet were restless: I wandered the city at a full clip, up and down the hills, my heels clapping through the Broadway Tunnel, then through the Stockton Tunnel, sometimes with a fistful of dim sum tucked inside my jacket pockets.

This was how, one afternoon, after taking a detour through Lower Nob Hill via Sutter Street, I walked into a (now-closed) gift shop that I had never noticed before — Brand Fury (780 Sutter Street) — and came face-to-face with Benji Wong. He was manning the counter and wearing a black leather jacket with a custom-printed T-shirt; the gray pinstripe fedora barely tamed his unruly elfin ears, which protruded pugnaciously no matter the season. He smiled, and his eyes crinkled as fine wrinkles spread across his cheeks.

“Hey, kiddo,” he greeted me.

信義和平

Trust, Peace

My friend who worked in one of the largest public relations agencies in town told me Benji was old-school San Francisco Chinatown. Back in the 1970s, when the Wah Ching and Joe Boys — two feuding gangs — waged ongoing bloody turf wars, most tourists linked Chinatown to violence, drug abuse, gambling, brothels, and seedy nightlife. By then, the big cabaret houses like Forbidden City (363 Sutter Street) had already closed, leaving only small clubs and dive bars like the Rickshaw Lounge in Ross Alley — the oldest alley in San Francisco — available for local nightlife promoters.

Steven Lee, the first Asian American nightclub owner to become entertainment commissioner in San Francisco, was an underage San Francisco State student with a fake ID when he first met Benji in the 1980s. He remembers that the parties took place on the second floor — and what separated Benji’s parties from all the other clubs was that he didn’t use live bands; he featured the Bionic DJ Randy Wong, a popular DJ who spun disco and R&B hits all night long.

This alley housed many of San Francisco’s houses of sin: gambling, opium dens, and prostitution

Today, if you enter Ross Alley, located just off Grant Avenue and sandwiched between Jackson and Washington Streets, the smell of burnt sugar from the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Company (56 Ross Alley) seduces you from the street. The street is now aglow with red lanterns floating above laundry-lined windows, and you’ll often see lion dancers practicing their choreographed kicks in the center of the brick-lined street. You couldn’t guess that a bloody gang massacre happened just around the corner decades before, or that, in the 1970s, the alley was merely a trough for rainwater, or that this was where two dive bars gave Chinatown clubbers something to do nearly every night of the week.

There’s no mention on the plaque in the alley that, in 1964, John Lennon and Ringo Starr stopped by the Rickshaw — that tiny little hostess dive bar where Benji once threw his weekday DJ dance parties for all the Chinese kids who were tired of being stared at outside of Chinatown.

This alley housed many of San Francisco’s houses of sin: gambling, opium dens, and prostitution. None of that mattered for Chinatown kids like Benji, who grew up in postwar America as native-born aliens. To him, Ross Alley was a sanctuary, a brief respite from the systemic and blatant racism surrounding the community, always.

忠孝仁愛

Respect, Love

By the time I met Benji, his life as the Bay Area’s biggest Asian party promoter was long behind him. He was retired and working part-time for an online events calendar website called SFstation.com. He lived alone, had never married, didn’t have any children, and he had been adopted by his best friend’s family, the Medinas, as a son and godfather. When Benji learned about my own family dysfunctions, he adopted me, too. Perhaps children who have been abandoned or discarded by their families are simply psychically attuned to each other — our antennae are especially intuitive.

How this happened was simple: One day, after bumping into each other again at the catering table of yet another press event — a few weeks after we met at Brand Fury — he simply called me on my BlackBerry and said, like it was the most natural thing in the world, “Hey, kiddo, have you eaten yet, and whach’you doin’ for Thanksgiving this year?”

After that, we met for yum cha every week at either New Asia (772 Pacific Avenue) or Dim Sum Club (2550 Van Ness Avenue; now closed), inside the da Vinci Villa Hotel. He ordered his flaky durian puffs and chrysanthemum tea while I stuck to oolong tea and lo mai gai—sticky rice steamed with coins of Chinese sausage, shiitake mushrooms, boiled peanuts, a slice of fatty pork belly, and one duck’s egg, orange as a clementine. Piece by piece and bite by bite, Benji’s life came into full focus as he told me his story.

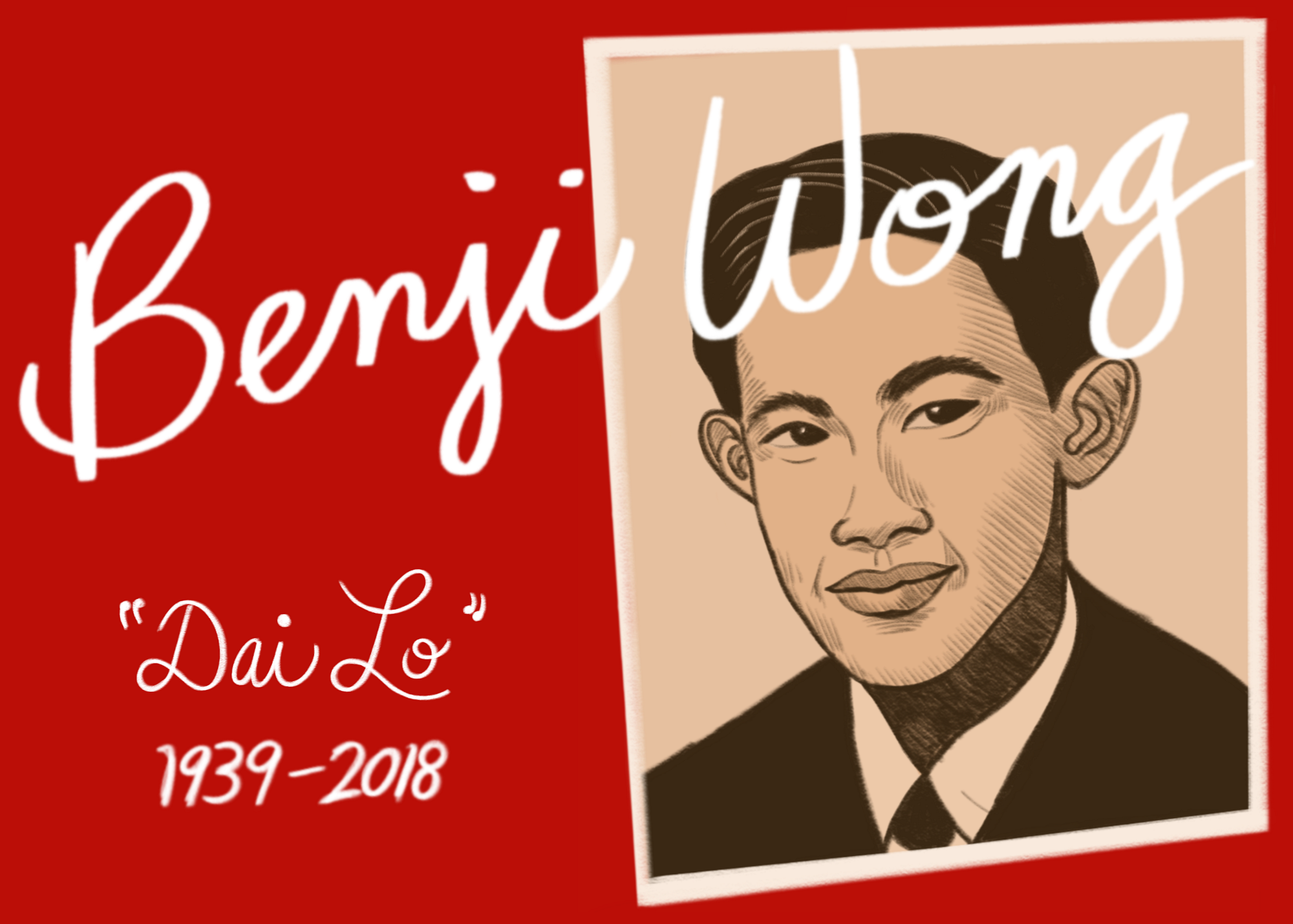

Benji was born in Oakland in 1939; his mother died soon after. Her name was Mabel, and he didn’t remember much about her except that she loved him dearly. His father remarried and dropped him off at his grandmother’s tiny apartment across from Cameron House, where Benji could see into the playground across the street, and never came back. It was there, at 920 Sacramento Street, where Benji would make lifelong friends with the children of Chinatown restaurant workers — other lonely children, like him. In 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act was lifted; he could then be an American citizen. His grandmother passed away. Benji joined the army the following year.

He was 18, the same age when I walked away from my family.

“I understand, kiddo,” he would say. “Sometimes, the best family is the one you choose for yourself.”

After the army, Benji rented an apartment up the hill where the groaning cable cars kept the time and worked in a post office. He almost married a girlfriend, but racism won. After her, he would only escort Miss Chinatown beauty pageant contestants and winners to his dance parties to entice young men to pay the steep door cover. He made many “sisters” of friends and often warned these proxy siblings of wannabe Don Juans who were nothing but trouble. His “brother” — his best friend — shared his love of live music, dancing, festivals, and concerts. The Medinas adopted Benji as their own, and he spent every holiday with them.

What they did for him, he did for me. After my boyfriend and I broke up, Benji cheered me up by taking me to the movies. He was a master of sneaking in food: Once, he handed me chopsticks and a bowl for wonton soup, lo mein, and char siu.

I’m not ashamed to admit that I’ve since taught my husband how to do this, so now movie night at the cinema is always dinner and a movie. With potstickers and more. Benji’s tradition became mine.

Benji and I remained family even after I left San Francisco, married, and became a mother. We would all drive up to San Francisco each year to ring in the Chinese New Year with him over yum cha. We called him Dai Lo—big brother. When we heard that Dim Sum Club was shutting down, my family and I went to eat there one last time and stayed until they kicked us out in the late afternoon, giggling and drunk on tea and sunshine and utterly in love with the city again.

I remember smelling the sweet aroma of honey-baked buns clinging to the fog steaming our windows and watching people with tanned skin and smooth faces, like mine, pausing to read the local newspapers.

I distinctly remember the first time I fell in love with San Francisco: During our third-grade school field trip, I looked out the bus window and saw sunlight dancing upon the glossy jade-green tiles and twin golden dragons atop Chinatown’s Dragon’s Gate at Bush Street and Grant Avenue, a pair of guardian lions flanked the gates with whiskers curled in mid-snarl, and that was it.

This was a city with people who had places to go — unlike Merced, that sleepy, cow-eyed town we had escaped that morning.

I remember smelling the sweet aroma of honey-baked buns clinging to the fog steaming our windows and watching people with tanned skin and smooth faces, like mine, pausing to read the local newspapers. In that brief glimpse, I saw my future: After school, I would find myself sitting across from Ted Fang, publisher, at AsianWeek’s headquarters and convince him to gamble on a new writer, just arrived in town.

I also vividly remember squinting to read what was carved in the middle of Chinatown’s concrete gate. It read:

天下為公

All Under Heaven Is for the Good of the People

Last year, just days before our shared birthday weekend, I received a text message from an unfamiliar phone number: “Benji in hospital. Come soon.”

When we stepped into the ICU, his room was open. I stifled a gasp after pulling away the heavy curtain: The chemotherapy had left his body deflated of blood and air, and a thin blanket disguised the snaking tubes below his waist. As I came closer, Benji lifted his eyes and pinched the sleeve of my white dress. He pulled down his respirator mask, and a long, ragged breath rattled through his hollow body as he wheezed, “Hey, kiddo. You’re here.”

“Of course,” I said, forcing a smile. “I’m here to throw you a birthday party.”

My husband and daughter entered with boxes of dim sum. Someone brought birthday cupcakes and a boombox. My daughter made a giant card, and everyone signed it with rainbow-colored markers; Benji held it closely to his face to read. When the party ended and his doctor stood at the door, I placed my framed photo near his bed. He gripped my hand and placed it on his chest, his heartbeat weak and slow.

“I never expected this,” he sighed.

“What’s to expect?” I said. “You’re family.”

“I’m so scared to leave you,” he whispered. He stared at me intensely and pressed my hand against his cheek. I started to sob. “Don’t cry, kiddo.”

“But I love you,” I hiccuped.

“I love you, too.”

點心

Dim Sum: To Lightly Touch Your Heart

Benji died a week before Christmas. He passed away in the night like a little mouse, curled up and gray. His adoptive family hosted a memorial service at Lefty O’Doul’s on Fisherman’s Wharf after the New Year. Everyone ate too much and danced poorly on the wooden parquet. It was what he would have wanted: one last party, just for friends and family.

As we said our goodbyes, Benji’s friend returned my framed photo to me. She told me that it had been a comfort to him, knowing I was there beside him. This small gesture had expanded his hope, and he left the world knowing he was much loved.