By Max Cherney

Two months ago Marc Souza and his neighbors in one of Oakland’s oldest neighborhoods, Temescal, got a notice in the mail from a developer telling them to move out before September 1. Souza and a handful of others are being forced out of their homes — Ellis evicted, really, without the official paperwork — to make way for a development that will almost certainly be upscale condos or rental units.

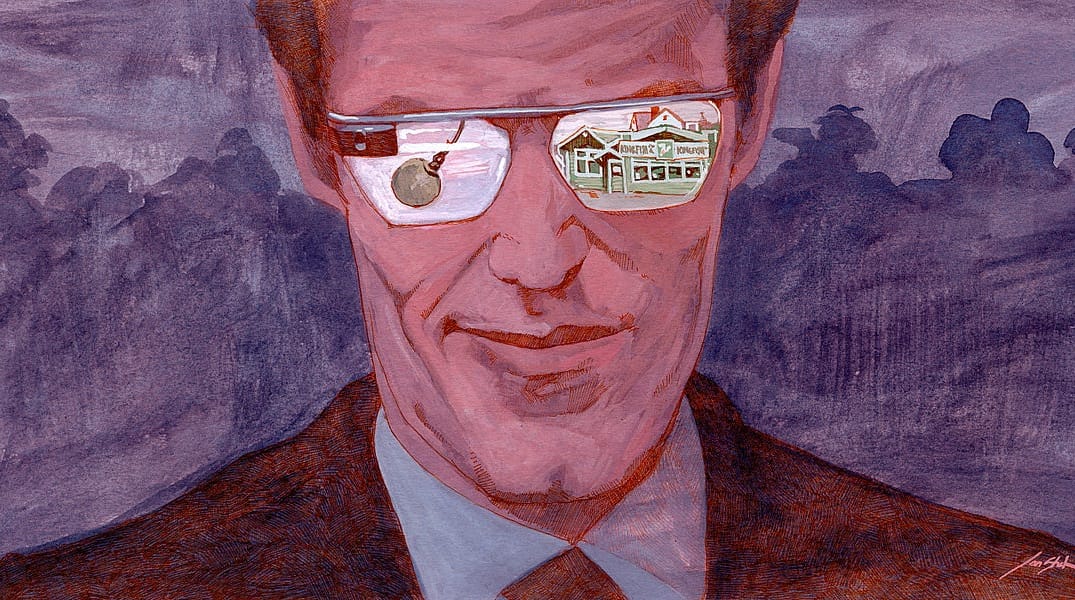

Talk of leveling the half-block, a small triangle of land where Telegraph and Claremont intersect — and where Kingfish Pub is located — has been underway for nearly a decade. But since the property changed hands last year, the new owners, Signature Development, have gotten serious about building condos on the dilapidated looking block.

Although the much-loved Kingfish has already agreed to relocate — the owners will lift the historic building and set it down on the new site close by — Souza and a couple of other tenants aren’t cooperating with the developers. That’s because they say Signature isn’t playing by the rules in their effort to get them out.

“I was gonna work with these people [Signature] until I received the letter that wasn’t legitimate,” Souza told me. “They wrote up that slip that was like, ‘These are your rights,’ but they weren’t honest about it.”

The developer doesn’t see it that way. In Signature’s eyes, it’s attempted to negotiate with the tenants in good faith, as well as give thousands of dollars in relocation money, the company’s senior vice president Paul Nieto explained. “We’re working with the tenants right now. We’re trying to improve the area, and we like the plans that were approved in 2006. We think it’s a good development.”

Strictly speaking, giving the tenants 60 days to clear out is not legit. And after sniffing around Oakland for about a month, I’ve figured out that these sorts of unofficial evictions — and by that I mean, off the books and not tracked by any sort of government body — are a common facet of life in a city that’s fast become a gentrification battleground.

“We don’t have a very good system for sorting,” Oakland’s rent adjustment program manager Connie Taylor said. She added, by way of anecdote, that she thought the vast majority, as many as 90 percent, were three-day pay-rent-or-get-evicted situations. Of the no-cause evictions, she said those involving the Ellis Act were uncommon, and that there were only between zero and seven filed every year — totaling about 47 for the last decade.

Unofficial evictions are a common facet of life in a city that’s fast become a gentrification battleground.

The thing about those stats is that they’re only for notices filed — no one knows exactly how many people are being evicted, and why it’s happening. In Souza’s case, he’s being forced out of his home, but there’s no official record.

And in some cases tenants can and do correct the cause for eviction — by paying rent or not subletting their place to Airbnb guests, for example. Others choose to fight it in court — as between three and four thousand people do every year, according to Adam Byer, a researcher at the Alameda Superior Court. So, that’s just to say that grains of salt apply to statistics from Oakland’s government.

The city does track some eviction information. Between 2007 and 2013 the number of eviction notices filed was steadily increasing. From 8,848 in 2007 and incrementally going up every year, finally arriving at 13,394 in fiscal year 2013, according to Taylor who manages the rent adjustment program.

This year, 2014, was the first that Oakland actually counted every notice; in prior years, officials sampled three months of eviction notices and based on that, guessed the year’s stats. For this past fiscal year, the city found that 10,910 residents got booted from their homes.

According to tenant advocacy group Causa Justa, many of those being evicted are longtime black and Latino residents in historic Oakland neighborhoods. “There are a lot of tenants who are uninformed of their rights and aren’t aware of rent and eviction control laws,” according to Marc Branco, the attorney repping Souza and a couple of others still living there. “There are many landlords in Oakland who have taken advantage of this, and who are attempting to ignore the eviction control ordinance. The pressure to do so is coming from perceived economic opportunity [from the boom].” Because of that, many evictions are never officially documented — a fact I confirmed with multiple sources, including a private investigator, who talked to me on the condition of anonymity because it could hurt business.

This year, 2014, was the first that Oakland actually counted every notice; in prior years, officials sampled three months of eviction notices and based on that, guessed the year’s stats.

Legally speaking, the letter demanding that Branco’s clients in Temescal move within 60 days isn’t following Oakland’s eviction control laws. “The notice stated that the landlord has plans to tear down the buildings, but doesn’t provide for a just cause for eviction that’s required by Oakland’s eviction control ordinance Measure EE,” he told me. “Signature’s 60-day notice is noncompliant.”

Ultimately, if the developer wants people out, they could and maybe should use the Ellis Act, which is just cause for eviction in Oakland. The Ellis Act is a controversial state law that grants landlords the ability to evict tenants in order to “go out of business.”

But invoking the Ellis Act would put a stain on the property’s title and impose severe limitations on renting unsold units in the planned condominium development should the developer be unable to unload their inventory. “Savvy developers want to keep their options open,” Branco said. “Therefore, it’s no big surprise that a developer would try to avoid invoking the Ellis Act and hedge his or her bets in an uncertain real estate market.”

Should Signature pursue that route, it wouldn’t have to pay the current tenants a cent in relocation cash. Unlike San Francisco’s relatively tough Ellis Act ordinance, which has withstood numerous court challenges, Oakland’s doesn’t require landlords to give Ellised tenants any move-out cash.

Signature has offered tenants thousands of dollars to move, with a bonus for an early exit, according to one of the 60-day move-out notices that I obtained. “We think we’re being fair with these people who are still living there,” Nieto told me when I asked about the settlement his company offered.

Unlike San Francisco’s relatively tough Ellis Act ordinance, which has withstood numerous court challenges, Oakland’s doesn’t require landlords to give Ellised tenants any move-out cash.

Oakland’s changing demographic is a result of the fact that insane housing costs in San Francisco have pushed lower- and middle-income households across the Bay in search of cheaper living.

The perceived financial opportunity of the Oakland housing market also leads some landlords to resort to even dirtier tactics, such as those attempting to evict Mustafa Solomon from his North Oakland apartment that he has lived in for 18 years. “They have not been dealing in good faith,” Solomon said. The landlords have not made needed repairs, and they’ve written multiple invalid eviction notices, according to Robbie Clark, a housing rights organizer with Causa Justa.

That’s happened in Souza’s case as well, according to him. After checking out the buildings on the block in Temescal myself, they all looked pretty rundown, so it’s no wonder that Branco’s building inspector came back with a laundry list of immediate repairs. When asked, Signature told me that it had sent out its own building inspectors.

Oakland’s changing demographic is a result of the fact that insane housing costs in San Francisco have pushed lower- and middle-income households across the Bay in search of cheaper living.

It’s not just longtime residents, people of color, and tenants who are uninformed of their rights who are getting evicted in Oakland. Lauren Gregory, 26, who moved to North Oakland in 2011 and works at a San Francisco startup, was evicted from her unit after her landlord tried to raise her rent illegally. “I’m feeling like my North Oakland neighborhood’s diversity, its community, is something that’s being threatened [by gentrification-related evictions],” Gregory told me. But she also notes that her situation is different from others. “My struggle is an inconvenience, I’m an able-bodied young person, and it’s not going to be terrible,” she said. “But it still sucks, I’m mad about it, it’s bullshit. I will no longer trust a home unless I really have it secured.”

Like Souza, Gregory hasn’t been officially evicted and won’t be included in Oakland’s official stats. And after looking into Oakland evictions for about a month, I’ve heard on numerous occasions — including from city staffers — that evictions without the paperwork are an ongoing problem.

As of publication time, Kingfish’s historic building remains on its site, with no word from the owners on when the pub is slated to be hauled to its new spot. Signature Development has until the end of the year to break ground on construction, otherwise it’ll have to apply for a new batch of permits from the city — a process that could prove time consuming. And Souza has resigned himself to the fact that he’s going to have to move out of the neighborhood, because on his salary he probably can’t afford to live there anymore. Like so many others in Oakland, gentrification has pushed him out too.